FOR decades, Dartmouth men have joked and bantered about "Vox clamantis in deserto." We hear the student talk of isolation, powerlessness, and discontent. Strangely, these terms sound familiar when one considers the plight of another group of people stranded at the other end of the continuum. Isolated, powerless and dissatisfied are the people living in the rural and urban slums of America. For well over a century, their voices have been crying in the wilderness. They went unheard until violence became the medium for amplification. Realizing that ours is not the only voice in the wilderness, Dartmouth has moved to bring the voices within earshot of each other.

As of 1967, the percentage of Blacks in the United States was approximately 11.1. Dartmouth's present student body is about 2 percent Black, including the students from Africa. This is a shocking disparity for an institution dedicated to higher learning for the purpose of perpetuating a better society.

When approached by students of the Afro-American Society, the admissions office explained that the reason for the small number of Black students on campus is that few apply, and those who are accepted often go elsewhere. It became apparent that a conscientious program of recruitment would have to be undertaken. The current program is a cooperative effort on the part of the admissions office, Project ABC, and the Afro-American Society. Members of the Society volunteered to travel to the various areas of concentrated Black populations in the country to seek out and encourage the application of qualified students to Dartmouth. It sounded simple enough, but theory and practice are two different things.

By coordinating one such trip to New York City myself, I learned first-hand what type of problems are involved.

First, what does the admissions office mean by "qualified"? Recent surveys and reports have shown that the antiquated standards of grading and testing are highly culture-biased and discriminate against the lower-class student as well as the average Black student. It is also now known that the student's environment has an effect upon his performance. So, for the average Black student, his high school record may have little to do with how well he would achieve in an environment as profoundly different from the ghetto as Dartmouth is.

Next, how do we encourage the student to apply to Dartmouth once we have located him? Students tend to listen more to their parents and counselors when making such decisions. My experience has been that the average adult in the ghetto has never heard of Dartmouth. Many come from the South and know only of the southern schools. In addition, few counselors see the sense in encouraging Black students to apply to any Ivy League school. Most of them are products of the state universities and they view the Ivy group as being out of the reach of any but the most superior students. Even in cases where they felt that a Black student might be able to survive academically, there was serious question as to how well he could hold his own in a social environment of vests, jackets and ties, and upper-class norms. The myth seems to persist that Black people must be in an environment where they can have women, wine and parties, and can shuffle their feet and pop their fingers in order to be happy. It doesn't seem possible to many people that achievement can mean a great deal to a Black youngster. So, with parents and counselors advising against Dartmouth, recruiters have to compensate by being extra encouraging. Dangerous limits are approached at this point, because to get a youngster's hopes up and then deny him admission crushes his own aspirations and reenforces the beliefs of the counselors as well. Obviously, we see the need for the College to establish stronger communication with the schools from which it expects to receive its students.

Finally, what happens if a youngster is accepted and decides to come to Dartmouth? The odds are that he will have certain deficiencies in English and math which have nothing to do with his ability but are simply attributable to impairments in his background. If the College is going to commit itself to improving the future potential of these students by giving them the opportunity to attend Dartmouth, then it must go one step further by recognizing the problems of the Black student and attempt to provide for some viable solutions. One of the most promising prospects is the summer Bridge Program which enables incoming freshmen to spend part of their summer in Hanover augmenting skills in which they are deficient.

Under the present circumstances, the recruiting effort has been quite successful. The College has made the program a part of its official policy and coordinated its resources to meet the task. The admissions office has solicited the support and assistance of Project ABC in locating promising candidates.

Through Project ABC, the College may obtain information from the nationally established Independent Schools Talent Search Program which is dedicated to locating promising students in areas which do not stimulate them to work to full potential. When the admissions office receives these names, an attempt is then made to contact the students and encourage them to apply to Dartmouth. This is best done by sending a volunteer from the Afro-American Society to talk to a number of these students in their high schools and their homes. The biggest problem to date is that we must try to arrange the trips around our academic and other schedules. Consequently, the number of recruiters is extremely limited. Nevertheless, we have managed to meet with over 100 candidates, many of whom may enter in the Class of '73.

It is encouraging to see Dartmouth answering the needs of the society which it serves in its capacity as an educational institution. However, the task is a difficult one and requires cooperation from many individuals. The alumni, hopefully, will be a source of strength through their support and assistance from their own home fronts. A word of encouragement and a critical interview as well as the multitude of other kinds of helpful things that alumni may do will be repaid many times over in the satisfaction of knowing that one has provided for a viable alternative to failure for a deserving young man.

Alumni interested in finding out more about what is being done and how they may be of assistance (which is sorely needed at this point) are strongly encouraged to contact the program's coordinator, A 1 Sloan '69, in care of Project ABC. Sloan has been visiting personnel in Detroit, Cincinnati, New York, Chicago, New Orleans, and elsewhere in the U.S. He will be visiting other cities in the months to come and would be interested in talking to alumni and others interested in what the College is doing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJames Marsh, Dartmouth, and American Transcendentalism

March 1969 By Douglas M. Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureFaculty Votes Reduced Status for ROTC

March 1969 -

Feature

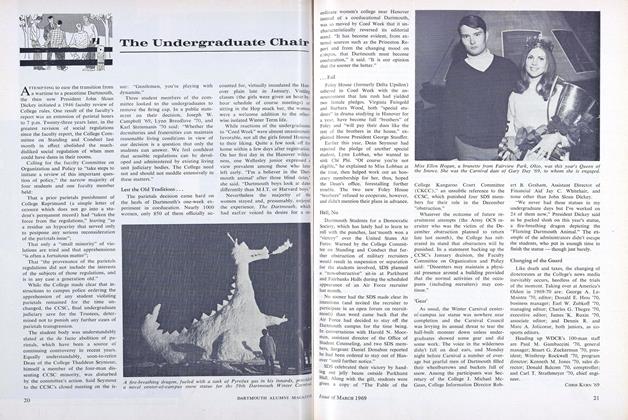

FeatureCOED WEEK: A Taste of the Future?

March 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

March 1969 By WALTER S. YUSEN, WILLIAM C. VAN LAW JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

March 1969 By THOMAS J. SWARTZ JR., HERMAN E. MULLER JR.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Art Show in Boston

OCTOBER 1971 -

FEATURE

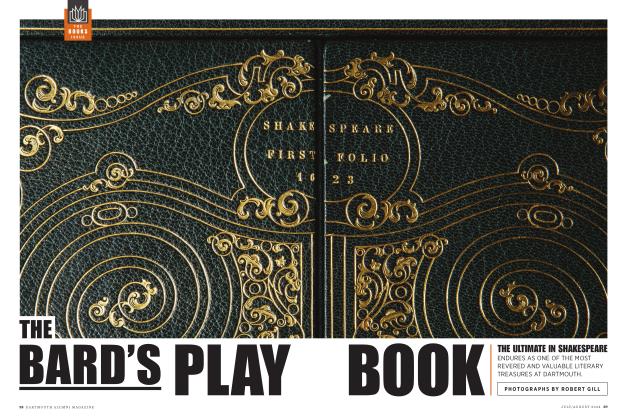

FEATUREThe Bard’s Play Book

JULY | AUGUST 2024 -

Cover Story

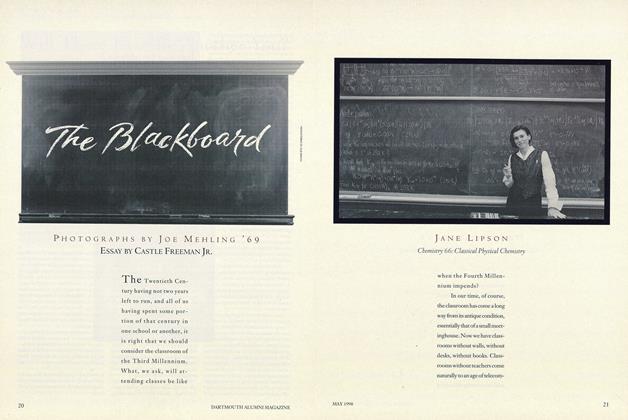

Cover StoryThe Blackboard

May 1998 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Humanist Ponders the Future of Liberal Education

June • 1985 By Charles T. Wood -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2012 By PHILIP MONTGOMERY