By Judson S. Lyon '4O. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1969. 209 pp. $4.50.

Born into the era of romantic poetry, into an age of such towering giants as Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, and Keats. DeQuincey is a fascinating anomaly. Professionally he seems to belong in the eighteenth century, for his forte was not poetry but journalism, so-called "hack work" for a succession of periodicals that came and went on the London and Edinburgh scenes; and the versatility of his writing, well over two hundred articles ranging in subject matter from Homer to Adam Smith, would have made him, one feels, a comfortable contemporary of Addison, Steele, Johnson, and Goldsmith. His personal life is another matter: that belongs in a novel by Dickens. Addicted to opium for the better part of his adult life (he died at 74), he burned up his modest legacy in ten years and spent the rest of his life hounded by creditors. Debtors' prison forever loomed just the other side of his inkhorn, the only thing that kept him out of it. Once, literally on his way to jail, DeQuincey was saved by a publisher who offered to settle his debts in return for a couple of articles.

For all that, as this book clearly shows, DeQuincey was unmistakably a child of the romantic era. Precocious as any of its greatest poets (though he did not really start writing until he was 36), he read the anonymously published Lyrical Ballads at the age of thirteen, instantly felt their impact as a revelation, and shortly became a devoted admirer of Wordsworth and Coleridge. Much of his most important work, including Confessions of an Opium-Eater and Suspiria de Profundis, is romantic in its autobiographical emphasis, and the very title of the Confessions recalls Rousseau. Like the major romantic poets, DeQuincey explored the world of dreams and the deepest mysteries of the human mind, and in "On the Knocking of the Gate in Macbeth," generally regarded as his finest single piece of criticism, he applies rigorous logical analysis —in the manner of Coleridge —to a profound psychological enigma. Too, just as Wordsworth developed a new language for poetry, DeQuincey refined the language of prose; Saintsbury described one of his Suspiria as a masterpiece of musical rhythm.

If this book has a fault, it lies in something apparently dictated by the format of the Twayne's English Authors Series: Germanic comprehensiveness. After a good, brief, readable account of DeQuincey's life, Professor Lyon gives a hundred-page survey of his work, and the result — somewhat like the work itself — is a potpourri: fact, description, summary, and comment on virtually everything DeQuincey wrote, rather than selective analyses of the most important pieces. The conclusion identifies the main features of DeQuincey's writing, however, and the book as a whole is a well- written, highly informed, stimulating introduction to one of the most encyclopedic minds of the English romantic period.

Mr. Heffernan, Assistant Professor of English at Dartmouth College, is the author of Wordsworth's Theory of Poetry and at present is preparing a book on English romanticpoetry and painting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

October 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe Transcending Great Issues

October 1969 -

Feature

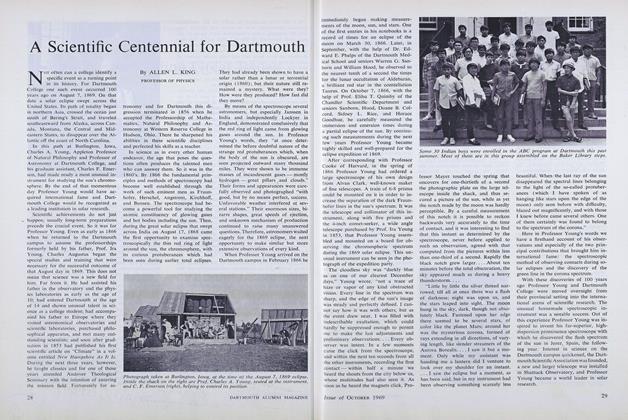

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

October 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureWhitewater Racing Gains New Status

October 1969 By JAY EVANS '49 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Draws Unusual Gifts

October 1969 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1969

Books

-

Books

BooksSECOND WIFE.

DECEMBER 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksCHARLES FRANCIS ADAMS JR. 1835-1915: THE PATRICIAN AT BAY.

FEBRUARY 1966 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksON POETIC IMAGINATION AND REVERIE: SELECTIONS FROM THE WORKS OF GASTON BACHELARD.

DECEMBER 1971 By DONALD OHARA '53 -

Books

BooksA SYNOPTIC HISTORY OF THE GRANITE STATE,

February 1940 By Herbert W. Hill -

Books

BooksAMERICAN NATIONAL GOVERNMENT

July 1952 By Jerome G. Kerwin '19 -

Books

BooksTHE DETROIT MONEY MARKET

June 1933 By R. V. Leffler