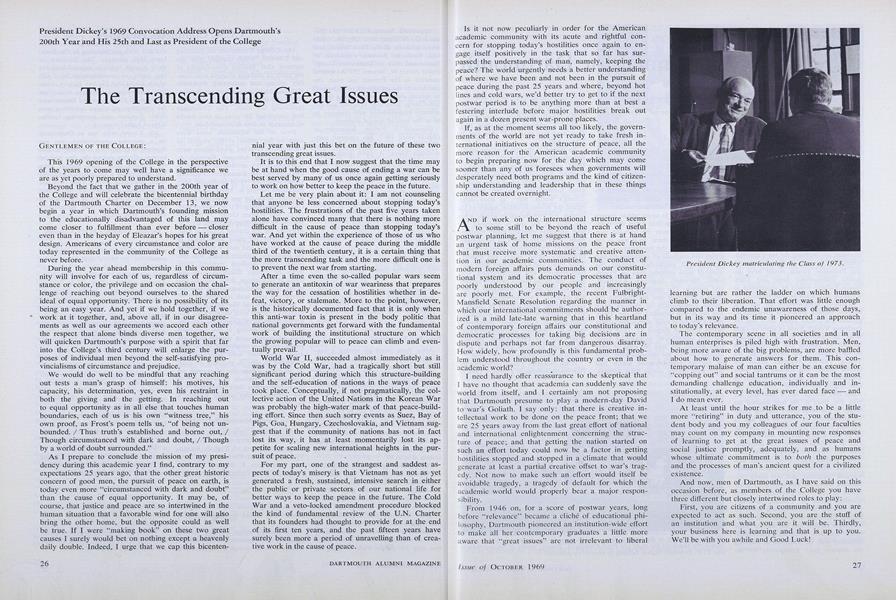

President Dickey's 1969 Convocation Address Opens Dartmouth's 200th Year and His 25th and Last as President of the College

GENTLEMEN OF THE COLLEGE:

This 1969 opening of the College in the perspective of the years to come may well have a significance we are as yet poorly prepared to understand.

Beyond the fact that we gather in the 200th year of the College and will celebrate the bicentennial birthday of the Dartmouth Charter on December 13, we now begin a year in which Dartmouth's founding mission to the educationally disadvantaged of this land may come closer to fulfillment than ever before — closer even than in the heyday of Eleazar's hopes for his great design. Americans of every circumstance and color are today represented in the community of the College as never before.

During the year ahead membership in this community will involve for each of us, regardless of circumstance or color, the privilege and on occasion the challenge of reaching out beyond ourselves to the shared ideal of equal opportunity. There is no possibility of its being an easy year. And yet if we hold together, if we work at it together, and, above all, if in our disagreements as well as our agreements we accord each other the respect that alone binds diverse men together, we will quicken Dartmouth's purpose with a spirit that far into the College's third century will enlarge the purposes of individual men beyond, the self-satisfying provincialisms of circumstance and prejudice.

We would do well to be mindful that any reaching out tests a man's grasp of himself: his motives, his capacity, his determination, yes, even his restraint in both the giving and the getting. In reaching out to equal opportunity as in all else that touches human boundaries, each of us is his own "witness tree," his own proof, as Frost's poem tells us, "of being not unbounded. / Thus truth's established and borne out, / Though circumstanced with dark and doubt, / Though by a world of doubt surrounded."

As I prepare to conclude the mission of my presidency during this academic year I find, contrary to my expectations 25 years ago, that the other great historic concern of good men, the pursuit of peace on earth, is today even more "circumstanced with dark and doubt" than the cause of equal opportunity. It may be, of course, that justice and peace are so intertwined in the human situation that a favorable wind for one will also bring the other home, but the opposite could as well be true. If I were "making book" on these two great causes I surely would bet on nothing except a heavenly daily double. Indeed, I urge that we cap this bicentennial year with just this bet on the future of these two transcending great issues.

It is to this end that I now suggest that the time may be at hand when the good cause of ending a war can be best served by many of us once again getting seriously to work on how better to keep the peace in the future.

Let me be very plain about it: I am not counseling that anyone be less concerned about stopping today's hostilities. The frustrations of the past five years taken alone have convinced many that there is nothing more difficult in the cause of peace than stopping today's war. And yet within the experience of those of us who have worked at the cause of peace during the middle third of the twentieth century, it is a certain thing that the more transcending task and the more difficult one is to prevent the next war from starting.

After a time even the so-called popular wars seem to generate an antitoxin of war weariness that prepares the way for the cessation of hostilities whether in defeat, victory, or stalemate. More to the point, however, is the historically documented fact that it is only when this anti-war toxin is present in the body politic that national governments get forward with the fundamental work of building the institutional structure on which the growing popular will to peace can climb and eventually prevail.

World War II, succeeded almost immediately as it was by the Cold War, had a tragically short but still significant period during which this structure-building and the self-education of nations in the ways of peace took place. Conceptually, if not pragmatically, the collective action of the United Nations in the Korean War was probably the high-water mark of that peace-building effort. Since then such sorry events as Suez, Bay of Pigs, Goa, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Vietnam suggest that if the community of nations has not in fact lost its way, it has at least momentarily lost its appetite for scaling new international heights in the pursuit of peace.

For my part, one of the strangest and saddest aspects of today's misery is that Vietnam has not as yet generated a fresh, sustained, intensive search in either the public or private sectors of our national life for better ways to keep the peace in the future. The Cold War and a veto-locked amendment procedure blocked the kind of fundamental review of the U.N. Charter that its founders had thought to provide for at the end of its first ten years, and the past fifteen years have surely been more a period of unravelling than of creative work in the cause of peace.

Is it not now peculiarly in order for the American academic community with its acute and rightful concern for stopping today's hostilities once again to engage itself positively in the task that so far has surpassed the understanding of man, namely, keeping the peace? The world urgently needs a better understanding of where we have been and not been in the pursuit of peace during the past 25 years and where, beyond hot lines and cold wars, we'd better try to get to if the next postwar period is to be anything more than at best a festering interlude before major hostilities break out again in a dozen present war-prone places.

If, as at the moment seems all too likely, the governments of the world are not yet ready to take fresh international initiatives on the structure of peace, all the more reason for the American academic community to begin preparing now for the day which may come sooner than any of us foresees when governments will desperately need both programs and the kind of citizenship understanding and leadership that in these things cannot be created overnight.

AND if work oh the international structure seems to some still to be beyond the reach of useful postwar planning, let me suggest that there is at hand an urgent task of home missions on the peace front that must receive more systematic and creative attention in our academic communities. The conduct of modern foreign affairs puts demands on our constitutional system and its democratic processes that are poorly understood by our people and increasingly are poorly met. For example, the recent Fulbright-Mansfield Senate Resolution regarding the manner in which our international commitments should be authorized is a mild late-late warning that in this heartland of contemporary foreign affairs our constitutional and democratic processes for taking big decisions are in dispute and perhaps not far from dangerous disarray. How widely, how profoundly is this fundamental problem understood throughout the country or even in the academic world?

I need hardly offer reassurance to the skeptical that I have no thought that academia can suddenly save the world from itself, and I certainly am not proposing that Dartmouth presume to play a modern-day David to war's Goliath. I say only: that there is creative intellectual work to be done on the peace front; that we are 25 years away from the last great effort of national and international enlightenment concerning the structure of peace; and that getting the nation started on such an effort today could now be a factor in getting hostilities stopped and stopped in a climate that would generate at least a partial creative offset to war's tragedy. Not now to make such an effort would itself be avoidable tragedy, a tragedy of default for which the academic world would properly bear a major responsibility.

From 1946 on, for a score of postwar years, long before "relevance" became a cliche of educational philosophy, Dartmouth pioneered an institution-wide effort to make all her contemporary graduates a little more aware that "great issues" are not irrelevant to liberal learning but are rather the ladder on which humans climb to their liberation. That effort was little enough compared to the endemic unawareness of those days, but in its way and its time it pioneered an approach to today's relevance.

The contemporary scene in all societies and in all human enterprises is piled high with frustration. Men, being more aware of the big problems, are more baffled about how to generate answers for them. This contemporary malaise of man can either be an excuse for "copping out" and social tantrums or it can be the most demanding challenge education, individually and institutionally, at every level, has ever dared face — and I do mean ever.

At least until the hour strikes for me ,to be a little more "retiring" in duty and utterance, you of the student body and you my colleagues of our four faculties may count on my company in mounting new responses of learning to get at the great issues of peace and social justice promptly, adequately, and as humans whose ultimate commitment is to both the purposes and the processes of man's ancient quest for a civilized existence.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and you are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you awhile and Good Luck!

President Dickey matriculating the Class of 1973

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

October 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

October 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureWhitewater Racing Gains New Status

October 1969 By JAY EVANS '49 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Draws Unusual Gifts

October 1969 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1969 -

Article

ArticleA Farewell Lecture

October 1969

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOur Captivating Compendium

APRIL 1978 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June • 1985 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryREVISED “MEN OF DARTMOUTH” POEM

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

Feature"The Record of Their Fame"

December 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2008 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69