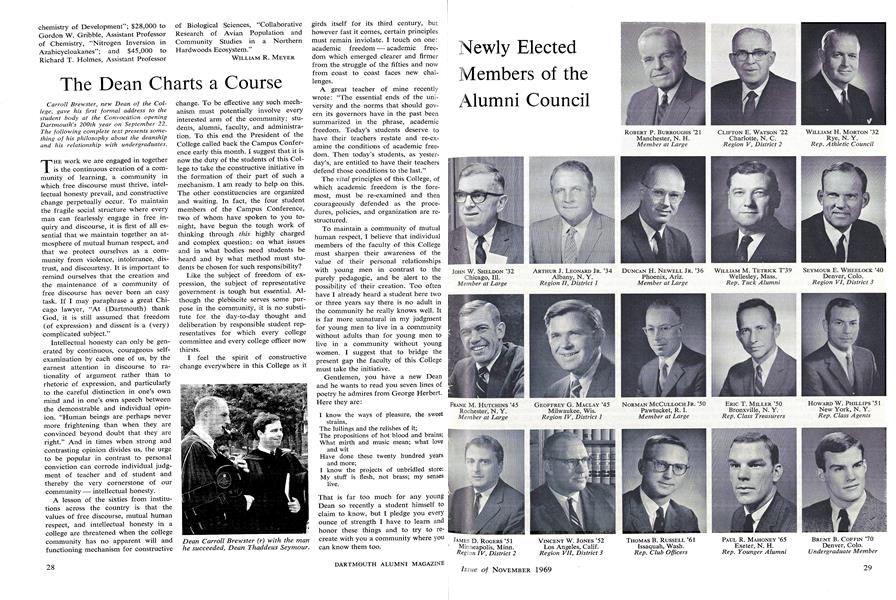

Carroll Brewster, new Dean of the College, gave his first formal address to thestudent body at the Convocation openingDartmouth's 200th year on September 22.The following complete text presents something of his philosophy about the deanshipand his relationship with undergraduates.

THE work we are engaged in together is the continuous creation of a community of learning, a community in which free discourse must thrive, intellectual honesty prevail, and constructive change perpetually occur. To maintain the fragile social structure where every man can fearlessly engage in free inquiry and discourse, it is first of all essential that we maintain together an atmosphere of mutual human respect, and that we protect ourselves as a community from violence, intolerance, distrust, and discourtesy. It is important to remind ourselves that the creation and the maintenance of a community of free discourse has never been an easy task. If I may paraphrase a great Chicago lawyer, "At (Dartmouth) thank God, it is still assumed that freedom (of expression) and dissent is a (very) complicated subject."

Intellectual honesty can only be generated by continuous, courageous selfexamination by each one of us, by the earnest attention in discourse to rationality of argument rather than to rhetoric of expression, and particularly to the careful distinction in one's own mind and in one's own speech between the demonstrable and individual opinion. "Human beings are perhaps never more frightening than when they are convinced beyond doubt that they are right." And in times when strong and contrasting opinion divides us, the urge to be popular in contrast to personal conviction can corrode individual judgment of teacher and of student and thereby the very cornerstone of our community - intellectual honesty.

A lesson of the sixties from institutions across the country is that the values of free discourse, mutual human respect, and intellectual honesty in a college are threatened when the college community has no apparent will and functioning mechanism for constructive change. To be effective any such mechanism must potentially involve every interested arm of the community: students, alumni, faculty, and administration. To this end the President of the College called back the Campus Conference early this month. I suggest that it is now the duty of the students of this College to take the constructive initiative in the formation of their part of such a mechanism. I am ready to help on this. The other constituencies are organized and waiting. In fact, the four student members of the Campus Conference, two of whom have spoken to you tonight, have begun the tough work of thinking through this highly charged and complex question: on what issues and in what bodies need students be heard and by what method must stu- dents be chosen for such responsibility?

Like the subject of freedom of expression, the subject of representative government is tough but essential. Although the plebiscite serves some pur- pose in the community, it is no substitute for the day-to-day thought and deliberation by responsible student representatives for which every college committee and every college officer now thirsts.

I feel the spirit of constructive change everywhere in this College as it girds itself for its third century, but however fast it comes, certain principles must remain inviolate. I touch on one: academic freedom - academic freedom which emerged clearer and firmer from the struggle of the fifties and now from coast to coast faces new challenges.

A great teacher of mine recently wrote: "The essential ends of the university and the norms that should gov- ern its governors have in the past been summarized in the phrase, academic freedom. Today's students deserve to have their teachers restate and re-ex-amine the conditions of academic free- dom. Then today's students, as yesterday's, are entitled to have their teachers defend those conditions to the last."

The vital principles of this College, of which academic freedom is the foremost, must be re-examined and then courageously defended as the procedures, policies, and organization are restructured.

To maintain a community of mutual human respect, I believe that individual members of the faculty of this College must sharpen their awareness of the value of their personal relationships with young men in contrast to the purely pedagogic, and be alert to the possibility of their creation. Too often have I already heard a student here two or three years say there is no adult in the community he really knows well. It is far more unnatural in my judgment for young men to live in a community without adults than for young men to live in a community without young women. I suggest that to bridge the present gap the faculty of this College must take the initiative.

Gentlemen, you have a new Dean and he wants to read you seven lines of poetry he admires from George Herbert. Here they are:

I know the ways of pleasure, the sweet strains, The lullings and the relishes of it; The propositions of hot blood and brains; What mirth and music mean; what love and wit Have done these twenty hundred years and more; I know the projects of unbridled store: My stuff is flesh, not brass; my senses live.

That is far too much for any young Dean so recently a student himself to claim to know, but I pledge you every ounce of strength I have to learn and honor these things and to try to recreate with you a community where you can know them too.

Dean Carroll Brewster (r) with the manhe succeeded, Dean Thaddeus Seymour.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

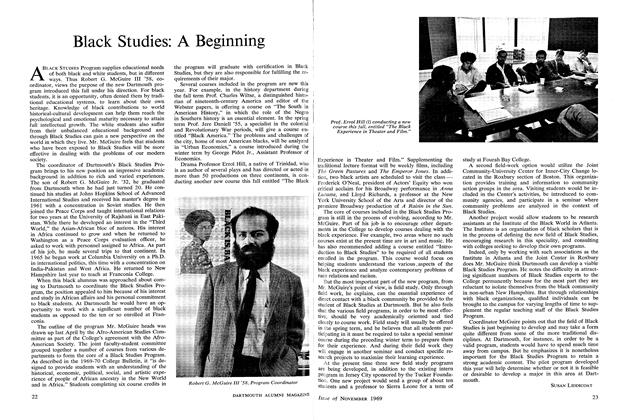

FeatureBlack Studies: A Beginning

November 1969 By SUSAN LIDDICOAT -

Feature

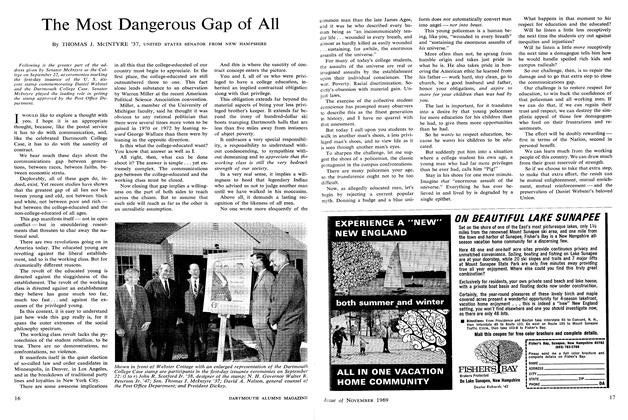

FeatureThe Most Dangerous Gap of All

November 1969 By THOMAS J. McINTYRE '37 -

Feature

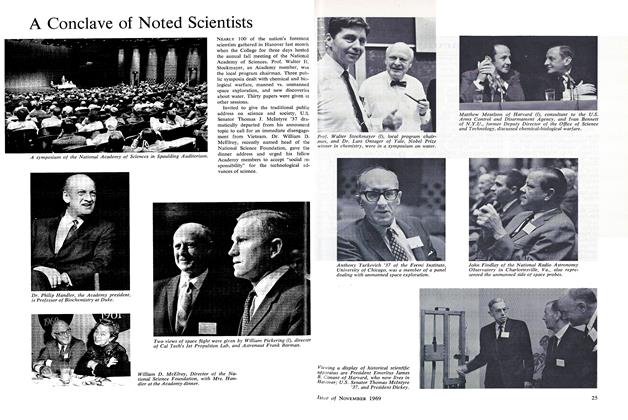

FeatureA Conclave of Noted Scientists

November 1969 -

Feature

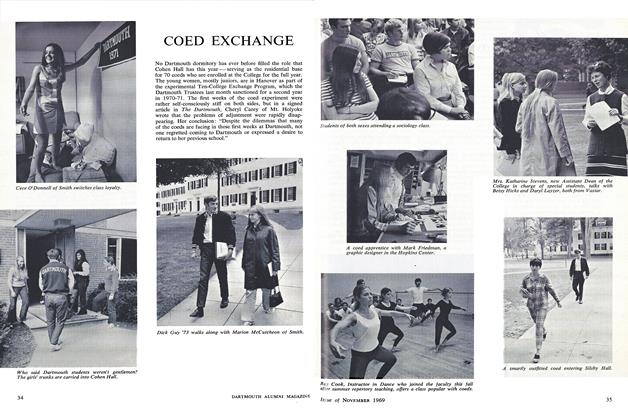

FeatureCOED EXCHANGE

November 1969 -

Article

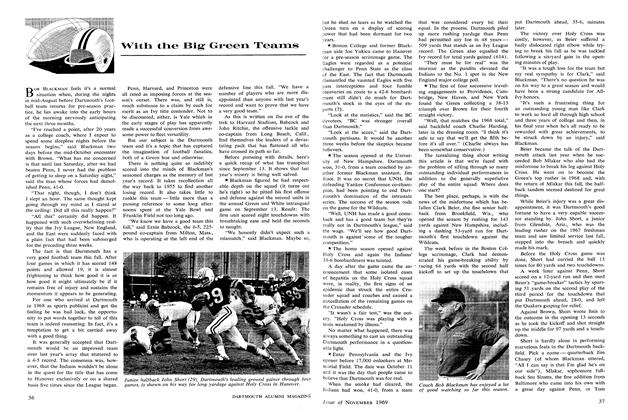

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

November 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1969 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Alumni Relations

MAY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureOne Answer for India

APRIL 1971 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Geography Department

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

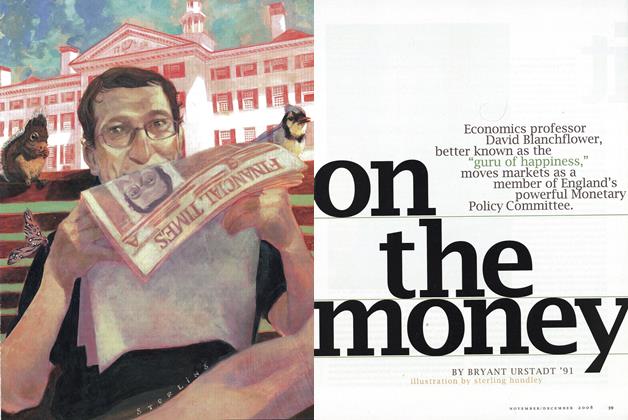

FeatureOn the Money

Nov/Dec 2008 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

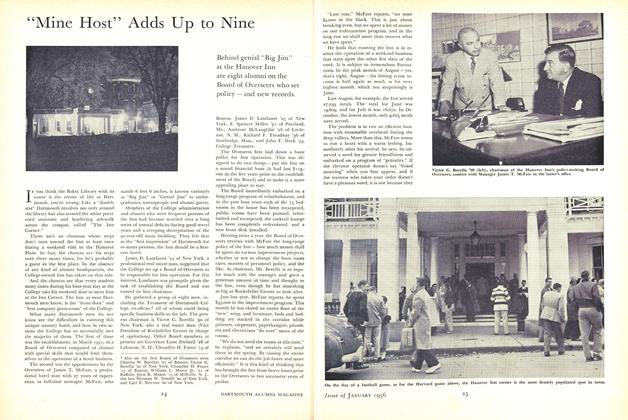

Feature"Mine Host" Adds Up to Nine

January 1956 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK FOR EVEREST BASS CAMP

Jan/Feb 2009 By PETER MCBRIDE '93