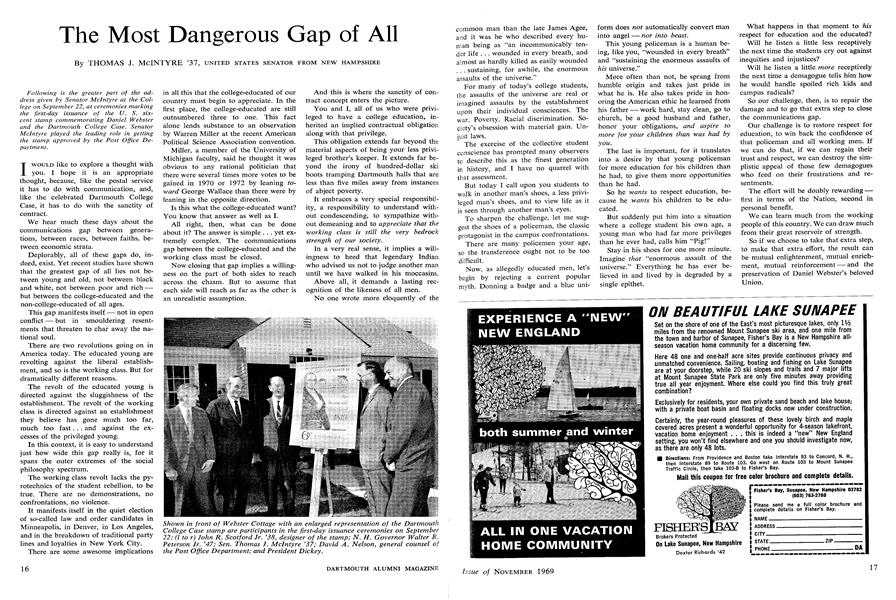

Following is the greater part of the address given by Senator Mclntyre at the College on September 22, at ceremonies markingthe first-day issuance of the U. S. sixcent stamp commemorating Daniel Websterand the Dartmouth College Case. SenatorMclntyre played the leading role in gettingthe stamp approved by the Post Office Department.

UNITED STATES SENATOR FROM NEW HAMPSHIRE

I WOULD like to explore a thought with you. I hope it is an appropriate thought, because, like the postal service it has to do with communication, and, like the celebrated Dartmouth College Case, it has to do with the sanctity of contract.

We hear much these days about the communications gap between generations, between races, between faiths, between economic strata.

Deplorably, all of these gaps do, indeed, exist. Yet recent studies have shown that the greatest gap of all lies not between young and old, not between black and white, not between poor and rich but between the college-educated and the non-college-educated of all ages.

This gap manifests itself - not in open conflict - but in smouldering resentments that threaten to char away the national soul.

There are two revolutions going on in America today. The educated young are revolting against the liberal establishment, and so is the working class. But for dramatically different reasons.

The revolt of the educated young is directed against the sluggishness of the establishment. The revolt of the working class is directed against an establishment they believe has gone much too far, much too fast. . . and against the excesses of the privileged young.

In this context, it is easy to understand just how wide this gap really is, for it spans the outer extremes of the social philosophy spectrum.

The working class revolt lacks the pyrotechnics of the student rebellion, to be true. There are no demonstrations, no confrontations, no violence.

It manifests itself in the quiet election of so-called law and order candidates in Minneapolis, in Denver, in Los Angeles, and in the breakdown of traditional party lines and loyalties in New York City.

There are some awesome implications in all this that the college-educated of our country must begin to appreciate. In the first place, the college-educated are still outnumbered three to one. This fact alone lends substance to an observation by Warren Miller at the recent American Political Science Association convention.

Miller, a member of the University of Michigan faculty, said he thought it was obvious to any rational politician that there were several times more votes to be gained in 1970 or 1972 by leaning toward George Wallace than there were by leaning in the opposite direction.

Is this what the college-educated want? You know that answer as well as I.

All right, then, what can be done about it? The answer is simple... yet extremely complex. The communications gap between the college-educated and the working class must be closed.

Now closing that gap implies a willingness on the part of both sides to reach across the chasm. But to assume that each side will reach as far as the other is an unrealistic assumption.

And this is where the sanctity of contract concept enters the picture.

You and I, all of us who were privileged to have a college education, inherited an implied contractual obligation along with that privilege.

This obligation extends far beyond the material aspects of being your less privileged brother's keeper. It extends far beyond the irony of hundred-dollar ski boots tramping Dartmouth halls that are less than five miles away from instances of abject poverty.

It embraces a very special responsibility, a responsibility to understand without condescending, to sympathize without demeaning and to appreciate that theworking class is still the very bedrockstrength of our society.

In a very real sense, it implies a willingness to heed that legendary Indian who advised us not to judge another man until we have walked in his moccasins.

Above all, it demands a lasting recognition of the likeness of all men.

No one wrote more eloquently of the common man than the late James Agee, and it was he who described every human being as "an incommunicably tender life... wounded in every breath, and almost as hardly killed as easily wounded . . . sustaining, for awhile, the enormous assaults of the universe."

For many of today's college students, the assaults of the universe are real or imagined assaults by the establishment upon their individual consciences. The war. Poverty. Racial discrimination. Society's obsession with material gain. Unjust laws.

The exercise of the collective student conscience has prompted many observers to describe this as the finest generation in history, and I have no quarrel with that assessment.

But today I call upon you students to walk in another man's shoes, a less privileged man's shoes, and to view life as it is seen through another man's eyes.

To sharpen the challenge, let me suggest the shoes of a policeman, the classic protagonist in the campus confrontations.

There are many policemen your age, so the transference ought not to be too difficult.

Now, as allegedly educated men, let's begin by rejecting a current popular myth. Donning a badge and a blue uniform does not automatically convert man into angel - nor into beast.

This young policeman is a human being, like you, "wounded in every breath" and "sustaining the enormous assaults of his universe."

More often than not, he sprang from humble origin and takes just pride in what he is. He also takes pride in honoring the American ethic he learned from his father - work hard, stay clean, go to church, be a good husband and father, honor your obligations, and aspire tomore for your children than was had byyou.

The last is important, for it translates into a desire by that young policeman for more education for his children than he had, to give them more opportunities than he had.

So he wants to respect education, because he wants his children to be educated.

But suddenly put him into a situation where a college student his own age, a young man who had far more privileges than he ever had, calls him "Pig!"

Stay in his shoes for one more minute. Imagine that "enormous assault of the universe." Everything he has ever believed in and lived by is degraded by a single epithet.

What happens in that moment to his respect for education and the educated?

Will he listen a little less receptively the next time the students cry out against inequities and injustices?

Will he listen a little more receptively the next time a demagogue tells him how he would handle spoiled rich kids and campus radicals?

So our challenge, then, is to repair the damage and to go that extra step to close the communications gap.

Our challenge is to restore respect for education, to win back the confidence of that policeman and all working men. If we can do that, if we can regain their trust and respect, we can destroy the simplistic appeal of those few demagogues who feed on their frustrations and resentments.

The effort will be doubly rewarding first in terms of the Nation, second in personal benefit.

We can learn much from the working people of this country. We can draw much from their great reservoir of strength.

So if we choose to take that extra step, to make that extra effort, the result can be mutual enlightenment, mutual enrichment, mutual reinforcement - and the preservation of Daniel Webster's beloved Union.

Shown in front of Webster Cottage with an enlarged representation of the DartmouthCollege Case stamp are participants in the first-day issuance ceremonies on September22: (I to r) John R. Scotford Jr. '38, designer of the stamp; N. H. Governor Walter R.Peterson Jr. '47; Sen. Thomas J. Mclntyre '37; David A. Nelson, general counsel ofthe Post Office Department; and President Dickey.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBlack Studies: A Beginning

November 1969 By SUSAN LIDDICOAT -

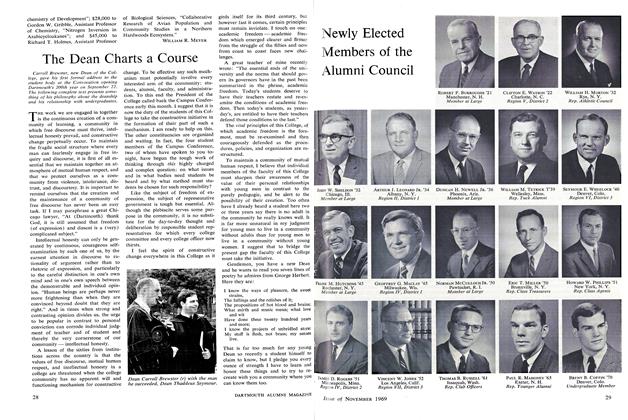

Feature

FeatureThe Dean Charts a Course

November 1969 -

Feature

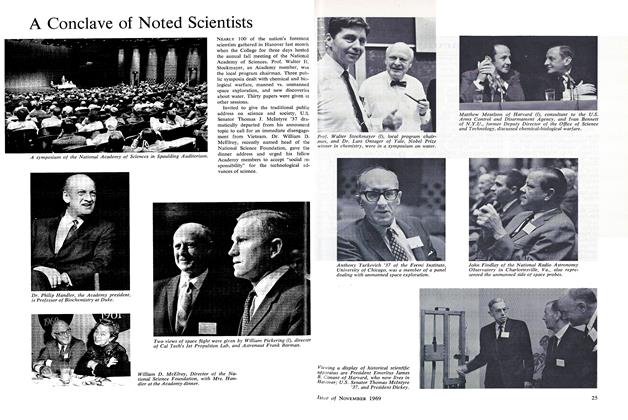

FeatureA Conclave of Noted Scientists

November 1969 -

Feature

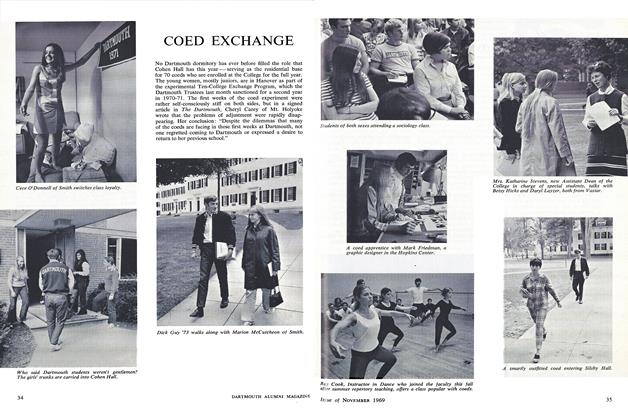

FeatureCOED EXCHANGE

November 1969 -

Article

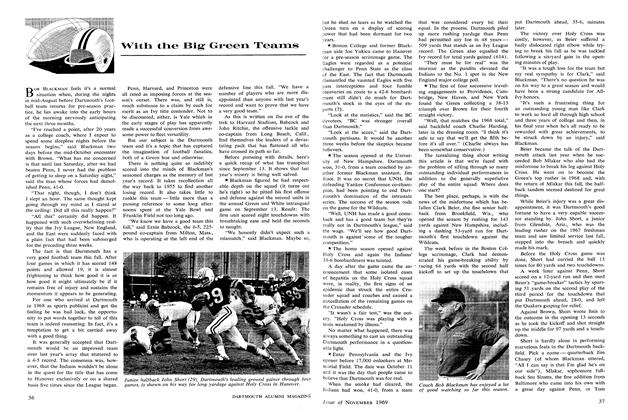

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

November 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1969 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70

Features

-

Feature

FeatureReunions Draw Big Turnouts

JULY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureJob Corps Director

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Features

FeaturesCenter of Attention

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By ABIGAIL JONES '03 -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureOne on One

MARCH 2000 By Mel Allen -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER