THERE is an intrinsic correlation here between the seasons of the mind and the seasons of nature. The fall term starts almost precisely on the first day of autumn imposing no sense of lost summer days but rather providing new energy, new perspectives on ourselves, and perhaps even new directions. The mind has had a chance to make the transition from summer and the mood is much more one of commencement than it ever is in the spring.

But the question remains: when we start the academic year what do we commence? What do people experience here at Dartmouth? I recently talked with an acquaintance of mine and in the course of our discussion he repeated an observation he had heard that "education takes itself too seriously." There followed a stream of observations and analysis about himself and the College which I have tried to recount here as nearly as possible in the fashion in which he spoke.

"This institution, as personal as it can be, is designed to educate some 3500 people every year," he said. "Its requirements and institutional expectations are only the average of the opinions offered by people of sharply differing outlooks. They cannot possibly fulfill the individual needs of each student here.

"I know the College must maintain standards," he continued. "Society demands standards and I suppose I do too. But what good do 'standards' do in developing my mind? Is it more important that I have the supposedly well-proportioned breadth and depth that standards and distributive requirements provide, or is it more important that I become deeply, intellectually involved in some subject, any subject? Does it really matter that I get three credits each term or does it matter more that I feel I have learned something? Does it really matter if I pass my courses or might I learn more from failing them, and thus have to face the consequences of that kind of failure?

"I can ask these questions and someone may tell me that all of these things are not mutally exclusive, that I can go to class and do well and still learn. Perhaps they are right. But the chances may be equally as good that they are wrong. For to go to class and do well, too often I must accept someone else's requirements. They set the patterns, not that the patterns are necessarily wrong but they are not my own. To become my own independent mind I cannot always follow their patterns. I must be free to roam, to pursue the thoughts and avenues of exploration that capture me. But too often I must push on to other things and leave myself intellectually unsatisfied.

"I find myself going to class, reading books and writing papers that hold no interest or meaning for me. I know the background which I am building up may be important and valuable to me. And yet I know that I have listened to so much without learning or remembering it, and that I drifted through courses two and three years ago and if asked to tell you about them now I could list the things I remember on ten fingers. I know that the things I have learned which will affect me most deeply for the rest of my life have been learned outside the classroom and that the things learned inside the classroom have been at best peripheral to my growth. As I observe my surroundings and my- self I understand that Dartmouth, and really any college, can only improve slightly on the principle of designing its programs around the average needs of its students, leaving the unique qualities in many students largely untended.

"I suppose one must finally realize and accept the fact that Dartmouth is really a training school, training you in its concept of what ideas, knowledge and skills you will need when you leave. Because of its role as a trainer, the College cannot be intellectually free. It has committed itself to have us respond to its teaching in certain fixed patterns. It has committed itself to having us respond to its standards in certain fixed patterns, and simply by virtue of its position in the American educational system it finds severe limitations imposed by its counterparts in secondary school and graduate education: Dartmouth cannot afford to allow me, for any significant period of time, to exist here completely in the pursuit of my own intellectual interests. Frankly, Dartmouth's reputation as a high-class trainer can only be enhanced by turning out well-trained students. I suppose it is too much of a risk to that reputation for Dartmouth to allow me any real freedom from its standards.

"I don't know, perhaps Dartmouth is right. It just seems somewhat ironic that in almost no academic institution in this country is there real intellectual freedom for the student. If you really think you have the toughness to be completely independent, and I suppose all of us have that feeling once in a while, then you've got to leave the College and go it alone."

At that he stood up and, throwing a handful of leaves onto the steps where we were sitting, suggested half-seriously that the only solution was to be a bum. Then he left.

He senses at times that he should devote himself entirely to pursuits of the mind, but he hasn't learned to trust that instinct yet. That is ironic because he is a highly instinctive individual. He only partially understands why he feels such a hesitation. He knows that the "education" which he and most others get in high school is not so much an education but a conditioning; a conditioning to fulfill prescribed assignments well, to memorize facts and to mold himself into an acceptable model for admission to college. Rather than being taught to act, he is taught to react. Secondary schools seldom teach students to think and therefore rarely develop in their students any real intellectual self-confidence. Those who have selfconfidence usually have it in spite of the schools. But as he makes these observations he is troubled by the very problem which he is discussing. He can't be sure that what he is saying is right. He can't know for sure that the problem doesn't lie with the system but with him.

He knows that his own mistrust of his intellectual impulses is tied to something characteristically American... the drive for accomplishment, for direction, and success. But he feels he must hang on to these American characteristics in some way, for if he loses them he loses a part of himself that has been condi- tioned for years and he is left outside the framework that has weaned him. The pressures from his mind and the conflicting pressures from his society at times leave him paralyzed, unable to write, study, or perform in the usual or expected patterns. However, he doesn't use this as an excuse, but rather is hard on himself for being transfixed by his dilemma.

He faces the problem, if this paralysis seriously affects his work, of doing poorly, receiving low grades and there-fore, in the eyes of society, of being inferior. He knows that he is not. He knows simply that he cannot work, but at times he is haunted by the fact that others will judge him for not having worked rather than for having fought one of the toughest and possibly most meaningful battles that a man will ever meet in the process of defining himself. He knows that those who never fight his battle have an easier time of it, but he knows he cannot avoid it because he would never then be able to face himself squarely again.

He recognizes other possibilities for dealing with his dilemma. He could leave college for a time in order to resolve it, but the war makes that both difficult and dangerous. And even if he did leave he fears that in working at a job, which is probably what he would have to do, he would resolve the battle by circumstance rather than by thought. The pressures of doing routine work much of the time and not having exposure to the College might turn his thoughts irrevocably toward the processes of getting ahead. Not that he would necessarily become insensitive or unthoughtful but that the fullest commitment of his mind to the nature of man's experience would forever after be impossible. He concludes, therefore, that he must make his choices and choose his directions in an atmosphere free from pressure which only the College can begin to approach.

Perhaps he should be criticized for being weak, for not being able to seize immediately upon a life plan or a goal. Nevertheless, his present ambivalence is just as much a part of his nature as purpose is a part of other people's natures; and perhaps it is just as much a product of his background and upbringing, in a society where want is not a factor for many and where the need to produce is not so urgent, as immediate purpose is a product of other back grounds and upbringings.

In truth, he believes he can define goals and purposes but he feels he needs all of his time at college to do it. His continuing dilemma is that even the college years are filled with pressures distracting him from this confrontation with himself.

Brent Coffin '7O of Denver, Colo., isthe first student member of the Dartmouth Alumni Council. Chairman ofthe Bicentennial Student Committee, hewas student head of the ABC Programlast summer and is active in OutwardBound and the Chest Fund. Last monthhe was Coordinator of the Peace Moratorium.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBlack Studies: A Beginning

November 1969 By SUSAN LIDDICOAT -

Feature

FeatureThe Most Dangerous Gap of All

November 1969 By THOMAS J. McINTYRE '37 -

Feature

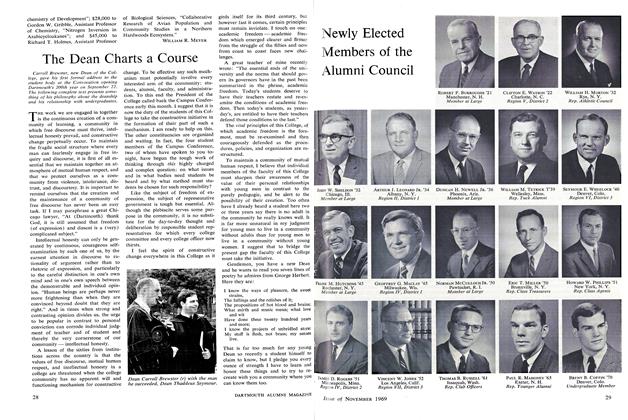

FeatureThe Dean Charts a Course

November 1969 -

Feature

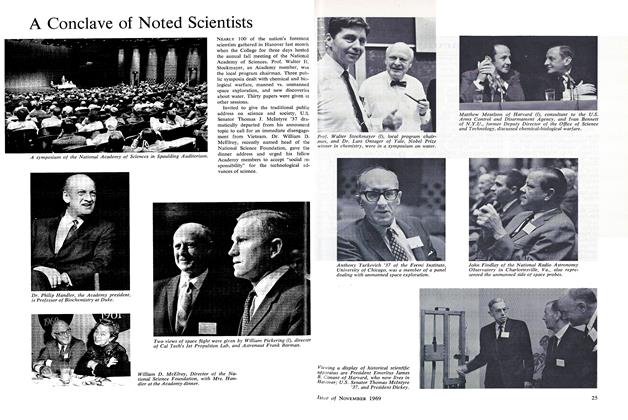

FeatureA Conclave of Noted Scientists

November 1969 -

Feature

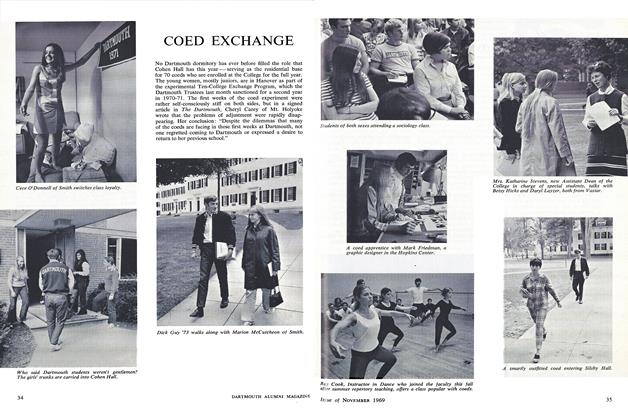

FeatureCOED EXCHANGE

November 1969 -

Article

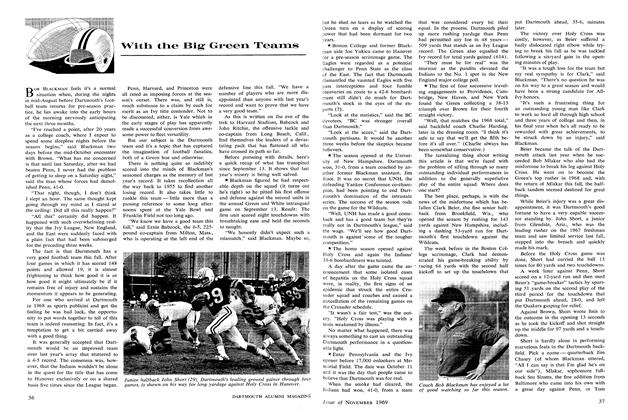

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

November 1969

WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70

-

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Primary Winner

MAY 1968 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70

Article

-

Article

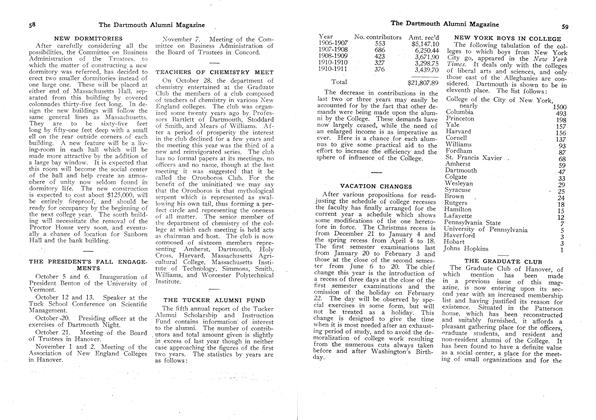

ArticleNEW YORK BOYS IN COLLEGE

December, 1911 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN PICTURE CALLED OFF

June, 1922 -

Article

ArticleHarvard Business School

December 1932 -

Article

ArticleThe Power of Philanthropy is the Power of Growth

April 2000 -

Article

Article2001

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Kristina Panettier -

Article

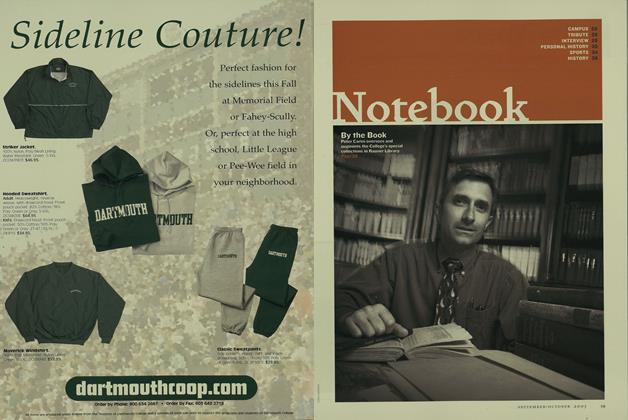

ArticleNotebook

Sept/Oct 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN