A Response to Dean Seymour

TO THE EDITOR:

Dean Seymour's "Of Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas" in the December Alumni Magazine is a fine example of the typical liberal-moderate response to the New Left in America today. As such, it deserves serious comment.

Dean Seymour accuses the New Left of irrationality, but he himself succumbs to the irrational tendency toward simplified stereotyping by implying that the "uniform" of the New Left is made up of "beards, beads, and bells." Even more serious is his implication that he regards these articles as obstacles to communication. In all my years at Dartmouth, I at least attempted never to let Dean Seymour's Bermuda shorts in the office and magic shows at the Hop prevent me from communicating with him on a rational level or from taking him as a serious person.

More importantly, though, Dean Seymour seems to argue that the rational process of learning and emotional responses to the conditions of society are incompatible. He seems to forget that man is not unlike a steam engine, in which his intellect acts as the mechanical machinery. The engine cannot run, though, without a fire to produce the steam; nor can the intellect serve its proper function without emotional responsibility.

The New Left is marching today because the structure of education in our colleges and universities stands in the way of, instead of aiding, emotionally responsible investigation of the problems confronting our society. Does not Congress' ability to cut off funds to students involved in anti-war demonstrations indicate not that the New Left is irresponsible, but rather that college administrators have neglected their responsibility to protect the independence of their institutions? Is it not a fact that this independence has been destroyed because American higher education today is structurally over-dependent on governmental sources of revenue? Dartmouth is no exception, either. At present, a great controversy is looming at Dartmouth between those forward-looking few who want Dartmouth's graduate programs to be structured on an inter-disciplinary basis and those who, for simple bureaucratic convenience, want each department to have its own graduate program. Dartmouth seems to have hired faculty in recent years not on the basis of their teaching ability, but rather because they are good "bureaucratic" academics who have the contacts to draw large governmental and foundation grants and thereby enrich the campus .financially. These are just a few of the tendencies dictated by the structure of the modern university which the New Left justifiably feel impedes responsible, rational, and emotionally valid education in America today.

Dean Seymour has "watched the assertion of raw authority as the only alternative to chaos" in response to the New Left's tactics, of which he paints a simplified scenario. As he stands by and watches, Dean Seymour might consider that there is another alternative available. That is to radically transform the structure of American higher education, to lift education out of its bureaucratic dependencies that destroy its independence, to reinfuse the modern university with emotional, as well as rational, responsibility. Dean Seymour tells us that the New Left has a foolproof plan for causing disruption. It is foolproof, though, only because the colleges and universities refuse to confront the very issues that the New Left use as their first step towards confrontation.

London, England

"In Sane Hands"

TO THE EDITOR:

To Thad Seymour a warm hand in congratulation for his excellent address, "Of Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas," from one such man with many such ideas. It strengthens my faith that the cockeyed world, for all its Faustian departures from Natural Order, is still (potentially at least) in sane hands.

Flagstaff, Ariz.

"This Admirable Paper"

TO THE EDITOR:

As you know I have written some critical letters to the College, mainly concerning the interference with the ROTC parade. Since then my wife and I have visited Hanover and while our principles have not been changed I think that we have broadened our understanding.

However, be that as it may, I thought it only fitting and proper to let you know that there are some of us who read all the magazine and some who hasten to write a laudatory letter when it is appropriate. This letter is one such and refers to the article by Dean Seymour in the December 1968 issue, "Of Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas." In my opinion, this admirable paper represents exactly my position and, I feel sure, the position of many who think as I do about the future of the United States and the duties of its citizens.

Lancaster, Pa.

Seymour for President

TO THE EDITOR:

I don't believe the Trustees have to look any further than the Dean's Office to find a successor for President Dickey. Dean Seymour's piece in the December Alumini Magazine, "Of Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas," once again demonstrates his fitness.

And what a President he would be! He knows thousands of alumni personally. Students like him and, more important, they listen to him! Personally, I've always felt that I'd like to turn out the type of man Thaddeus Seymour is.

Eugene, Ore.

Newton Notes (Cont.)

TO THE EDITOR:

Whether or not you will continue printing letters in regard to James Newton's valedictory, the subject has held so much interest here that perhaps one more amen is not inappropriate.

For me all those letters you have so fortuitously compiled seem a story in themselves — a chronology of our years, our people and our thoughts; and in reviewing them my continuing response has been: Thank God for the younger generation! For somewhere after the Class of 1951, or thereabouts, something new takes over and expresses, at least to me, a firmer conviction, a clearer majority view. This view is proud of the Dartmouth man who can "tell it like it is," who can shoulder the unsavory fact that our country may be wrong, and can see that all the injustices of inequality, poverty and war in the world will continue only so long as there exist those who can so readily accept and condone them.

James Newton needs no expressions of support, for his convictions are secure. The ideas, however, he so uncompromisingly proclaims deserve all we can muster.

New Haven, Conn.

TO THE EDITOR:

The continuing correspondence on the Newton valedictory has come down to some pretty silly name-calling and some more serious accusations. While we may be amused by the former, there is nothing funny about charges of disloyalty, treason, and cowardice. They deserve answers.

In the first place, those alumni who feel that Newton's remarks reflected unfavorably on the College may take comfort in the fact that his ideals and. moral convictions originated with his Quaker background. Others will also find comfort in the belief that Dartmouth strengthened those ideals.

As for his speech, upon rereading, it strikes me as a remarkably good analysis of what is wrong in America and what should be done about it. He's in good company on most points. To be sure, he would have offended fewer alumni had he not criticized American militarism in such vivid language. After all, few of us like to think of the world-wide deployment of American armed forces in such terms, much less face up to the reality of their tactical and moral vulnerability. But isn't one good measure of maturity the ability to see and admit one's own errors? maturity the ability to see and admit one's own errors?

The charges of disloyalty or treason are sheer nonsense. Self-styled patriots may cite Stephen Decatur's "... our country right or wrong!" in justifying anything we may do. But they forget his qualifying admonition that if our country is in the wrong, we should try to correct it. Newton spoke in the finest traditions of democracy when he cried out in the wilderness of New Hampshire (and our own misguided notions) against those policies which increasing numbers of Americans — possible a majority — now truly regret.

The most absurd charge is that of cowardice. One wonders by what twisted logic a man is branded as "cowardly" who has the courage to face exile or many hard years in prison for his moral convictions. Indeed, one of the more disgraceful aspects of our Asian misadventure is the way we are making political prisoners of substantial numbers of our most gifted and conscientious young men, who cannot condone our destructive behavior in Vietnam. After all — America's security was not threatened, world opinion is against us, and an undemocratic draft system has been used by politicians to carry on a war they dare not ask the Congress to declare.

One final note. I am distressed that so many alumni seem not yet to realize how universal the opposition to the Vietnam war is among all college students, including those at Dartmouth. This fact was detailed in an article in the July 20 New Yorker magazine (p. 56 "Our Far-Flung Correspondent: College Seniors and the War"). I'm sorry that reference to Noel Perrin's article did not get wider attention.

Watchung, N. J.

TO THE EDITOR:

The Senior valedictory of lames W. Newton 1968 still causes comment from concerned alumni, and well it might. Along with the problems of how to best deal with our cities and our poor, the war in Vietnam raises some basic issues about American values and society. It has helped many of us realize what our nation has become.

We have the potential and the will to send a man to the moon, so we do it. We have the willingness to spend over $80 million each day to maintain a corrupt but friendly government in power (we hope) in Saigon, so we send over 500,000 of our troops to the Asian mainland, regardless of the destruction and bloodshed it brings and the divisiveness it causes. What we seem to lack is the willingness to solve the problems of our poor and our cities, solutions to which will require many millions of dollars and large pools of manpower.

For five weeks in the spring of 1967 I toured the hospitals in Vietnam from DaNang to the Mekong delta available to serve Vietnamese civilians. I saw 8-year-old boys old boys who had been hit with napalm children paralyzed from bullets our soldiers fired. I saw a small part of the destruction of that country which we have caused and it made me wonder about where our interests really do lie.

James Newton is to be heartily congratulated for speaking the truth as he, and I, and others like us see it. As Senator Ribicoff said to Mayor Daley of Czechoslovakia West, so I would say to alumni and others who criticize Mr. Newton: "How hard it is, how hard it is to face the truth!" May the College continue to produce many Newtons.

Staten Island, N. Y.

TO THE EDITOR:

Mr. Newton's valedictory address has been condemned by many alumni over the past half year, yet very few letters have come in from '68s (or at least they have not been published). Though never knowing James Newton personally, I would like to explain my reasons for applauding his address.

I do not believe that most men in our Class wouldn't fight for their country if they considered the cause just. Students all over America are rejecting the my-country-right-or-wrong philosophy that has long prevailed and are substituting a new sense of moral conscience to guide their political decisions. This new generation realizes that the future integrity of our democratic way of life necessitates a genuine understanding of people that choose to live much differently than we do; that America cannot hope to succeed in superimposing its culture and political ideology on others. Mr. Newton is called a "coward" and a "traitor" because he sees the wisdom in ending a war that cannot be won ideologically, even if a military victory could be accomplished at a cost enormously out of proportion to its worth. I salute a sensitivity that would rather have our nation lose some intangible political prestige than more American lives.

Adaptability, the capacity to recognize a poorly developing situation and favorably change the direction of attack, is an important thing to learn. James Newton, in contrast to many alumni who slandered him, has not failed Dartmouth or his country in learning this lesson. His address was a plea for change, in the hope that the U.S. could then proceed to realistically rear-was a call for action aimed at alleviating the numerous problems of rural and urban America. No American wants to see his country get defeated, yet the prospects of a "victory" in Vietnam, whatever that means, are at best disheartening. Many young people, myself included, are shocked when so many supposedly educated people become appalled at words realistically spoken.

It is not my purpose to deify Mr. Newton. But if the words "coward" and "traitor" come to embody his sense of concern for American welfare, then" I for one would proudly wear such labels next to my name.

Durham, N. C.

View from the End Zone

TO THE EDITOR:

Every year the Dartmouth alumnus who wants to see the Harvard-Dartmouth game and has non-Dartmouth friends is faced with one of three choices. One, sit in his class section and get fair to poor seats and to hell with where his friends sit. Two, sit with his friends and depend on the radio for news of the game. Three, give the whole thing up and stay home.

Seats eight rows up from the playing field in a section behind the goalposts are scarcely worth $6.00. The older grad sitting in front of us put into words my thought when he said, "I had better seats when I was a freshman." I could add to that and say in truth that the 6-8 tickets I buy every year have gotten progressively worse. I expect that next year I will probably be to the Harvard side of the goal posts.

Fellow Alumni unite! Protest the only way we can — money.

I intend to boycott all alumni funds and hold back what I ordinarily would give until I see what kind of seats I get next year.

Why should we who help support the College accept "poor relations" type treatment? Somebody sits on the sidelines between the 20-yard line markers, and it isn't us. I can get better seats on the Harvard side, but I'll be damned if I will.

Westwood, Mass.

Edward Tuck at La Turbie

TO THE EDITOR:

While visiting one of my daughters in Monte Carlo this winter I inspected an historic site situated at La Turbie high in the hills above Monte Carlo. It is known as the "Trophy of the Alps," and was dedicated in 6 B.C. by the Romans to celebrate the successful campaign of Caesar Augustus the subdue the Alpine nations. The Trophy was erected on the Via Aurelia at the threshold of the Alps on the spot where the Roman generals had their headquarters.

Over the centuries the Trophy had fallen on ill times and was in need of restoration. Much to my pleasure and surprise I learned that funds for the restoration were supplied by the famous Dartmouth alumnus, Edward Tuck. At the restoration ceremony in 1934 and here I quote from a brochure: "M. Hanotaux, historian and former Foreign Minister, acknowledged the debt to Mr. Tuck, whose name, he said, was not only graven forever on the monument itself, but on the hearts of all Frenchmen who knew him, as were the exploits of his compatriots at St. Mihiel, Chateau-Thierry, and Bois Belleau."

Mr. Tuck in handing over the golden key of the edifice as well as that of the museum his liberality had provided said: "If this Trophy attracted me by its splendid situation, the beauty of its conception, its illustrious history and its exceptional rarity, this was not all. For above these considerations it bears within itself two magnificent and generous ideas, the opening of the Western world to classical culture and the Pax Romana, which gave Europe three centuries of peace and prosperity."

In the small museum mentioned there is a bust of Mr. Tuck and a framed photograph of Mrs. Tuck.

As many Dartmouth men know, Mr. Tuck lived in Paris but spent his winters in Monte Carlo. His generosity to Dartmouth is well known. However, his interest in this project was unknown to me and possibly to other Dartmouth men hence this letter.

Monte Carlo

Mr. Bridges is a James B. Reynolds Scholarfrom Dartmouth at the London School ofEconomics.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

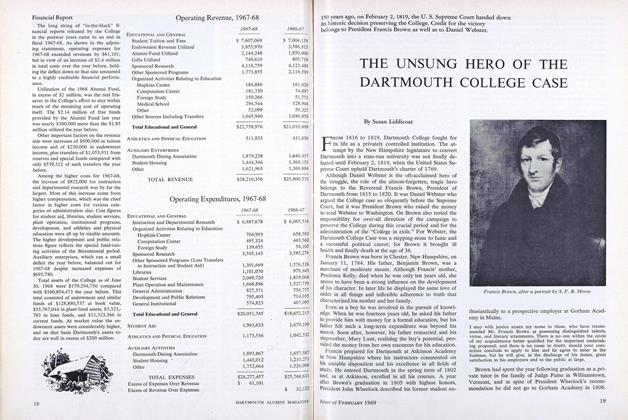

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

February 1969 By Susan Liddicoat -

Feature

FeatureThe Bearing of the Green

February 1969 By Mary B. Ross ('38) -

Feature

FeatureA Call for Equal Opportunity

February 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Student View of the Crisis, 1816-19

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCONCERNING BILL

January 1917 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

DECEMBER 1926 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1932 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1933 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA Home For Native Americans

Novembr 1995 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2009