SOME say it was an incendiary kind of day, June 16, 1968. Discordant and disturbing it surely was — like the world which the Class of 1968 has inherited.

But to one parent, a died-in-the-Green charter member of the Dartmouth Auixiliary, it was a day of deep pride, rampant nostalgia, nagging regret — all with a generous admixture of plainrelief.

The pride was in a son graduating from his father's and his grandfather's college and in that college for the kind of man it helps to form.

The nostalgia was for other generations and other Commencements, an inescapable and not entirely reprehensible sentiment, proclamations of some hard-nosed realists of the new generation to the contrary notwithstanding.

The regret was at losing the latest direct link with the College.

There was relief too. Incendiary though the Commencement may have seemed to some disenchanted alumni and parents, I was grateful that the conflagration was confined to verbal pyrotechnics. My son had graduated; Dartmouth Hall had survived. It was a fortuitous departure from family tradition. The original of that magnificent edifice had burned to the ground when my father, Eliot Bishop '01, was in his final year at the Medical School; its replica succumbed to fire when my husband, Robert H. Ross Jr. '38, was a freshman.

President John Sloan Dickey closed his Valedictory to the Class of 1968 with the familiar assurance, "... in the Dartmouth fellowship, there is no parting." I'm prepared to believe it and, risking impertinence, amend his statement to include the Dartmouth "sisterhood." There too, I contend, there seems to be no beginning and no end, only a happy continuum. Whether one is brought up in the faith, marries into it, or is converted still later by a student son, there is no denying the involvement of the Women of Dartmouth in the College.

As a Dartmouth daughter, niece, sister, cousin, wife, and mother, I bow to no woman in the vicarious influence of the College on my life. I claim close kinship, distaff-style, to the Classes of '95, '01, M'04, '36, T'37, '38, and '68 and, tangentially, to heaven knows how many more. This happy association of family and College dates, I have recently learned, from Asa Carpenter, first minister of the Congregational Church in Lower Water-ford, Vermont, and a member of the Class of 1795. What collateral degree of cousinship we share it would require the awesome facilities of the Kiewit Computer Center to ascertain, but we are descendants of a common ancestor, one William Carpenter of Rehoboth, Massachusetts.

Reared to the strains of Eleazar, disciplined from birth to the "Alumni Fund-before-groceries" mystique, conditioned by the rigors of successive '01 and '38 reunions, I have lived constantly and even contentedly under the spell of my own Men of Dartmouth. In all due humility, I submit that my credentials entitle me to speak with some authority on membership in the Dartmouth Auxiliary and the rights, privileges, and immunities there-unto appertaining.

My grandmother, Sarah Carpenter, attended her first Commencement Ball at Dartmouth in 1853. Family legend has it that she journeyed downriver from St. Johnsbury by horse and buggy to see a cousin graduate. College records reveal no identifiable cousin in that class, although an illustrious fellow townsman, Henry Fairbanks, later Professor of Natural Philosophy and History and still later a Trustee, did graduate that year.

" Parts of the tale may well be apocryphal. It was with some dismay that I learned the Connecticut and Passumpsic Rivers Railroad sent two daily trains south from St. Johnsbury to White River Junction in 1853, in roughly the same time the Vermont Transit Company takes in 1968 to cover the same route — some commentary in itself on progress in public transportation! But legend dies hard, and the romantic horse-and-buggy version sets better.

The 1853 Commencement was another Dartmouth Spectacular. As the NewYork Herald proclaimed the event, "... Rufus Choate, a graduate of Dartmouth, in the class of 1819, and the greatest American orator now living, is to pronounce a eulogy upon Daniel Webster, a graduate of the same institution in the class of 1801, and the greatest orator, American born, living or dead." (The same reporter was less sanguine about one of the peripheral speeches of the week, which he characterized as "well enough, but nothing to invite a man to.")

Hanover was in tumult for the grand occasion, so much so that it was necessary to appeal for order for the "funeral services." Students were crammed in the windows of the College Church, and one man, an alumnus recalled years later in The Dartmouth, "had got a narrow plank and fastened one end of it against the chapel and the other lay on the window sill. The man lay prone on it. It was an uncomfortable position, for it slanted down toward the chapel rather steeply." Discomfort must have ripened into agony in time. Whatever Mr. Choate's other oratorical virtues, brevity was not among them: the eulogy went on for two and a half hours.

Many of the visitors were disgruntled as well as uncomfortable. The St. Johnsbury Caledonian noted on the following Saturday that the crowd "would have been nearly a third larger could the people present have all got into the house." It concluded, a bit testily: "The people of Hanover owe it to the public to provide some commodious building for the annual Commencement Exercises. It is hardly good treatment to people residing at a distance to be shut out by the limits of the house, or excluded by introducing favorites by a private entrance." Whether Grandmother was among the favorites or one of those excluded I never learned. The initials after the newspaper account are the same as hers, but the conclusion that the huffy reporter was a fifteen-year-old girl, however precocious, demands too much of credulity.

MY father felt a special affinity for the subject of the 1853 eulogy. Not only were he and Daniel Webster both '01, he liked to say, but they shared a birthday.

He was twice blessed, in his view, in taking both his undergraduate and medical degrees at Dartmouth. At his first Commencement he claimed facetiously to have led his Class, which he literally did — by dint of the alphabetical precedence of the letter "B" and the academic precedence of the A.B. His was the class to hear at its Baccalaureate Service that celebrated exhortation by President William Jewett Tucker: "Seek, I pray you, moral distinction.... Do not expect that you will make any lasting, or any very strong impression in the world through brains without the use of an equal amount of conscience or heart" — still an appropriate injunction to the liberally educated man.

At his second Commencement, Father was one of ten men, only four of whom were college graduates, to receive their M.D. degrees. Although the Medical School was small in those days and the facilities primitive by contemporary standards, the clinical experience gained from accompanying those almost legendary professor-practitioners, Dr. Gilman Frost and Dr. John M. Gile, on their varied rounds was remarkably rich and broad. Their example was to shape much of my father's personal devotion to his patients and his encouragement of young physicians throughout his professional life. And the harrowing tales of winter night calls by horse and sleigh to isolated farm housespossibly somewhat embellished in the telling by time made fine fireside yarns.

Father was one of the true believers in what has been described, with some accuracy, as the "Dartmouth religion." He came to Hanover in the fall of 1897, already thoroughly evangelized by his brother, Joseph Warren Bishop '95, from whom he inherited the nickname 'Bunker." Having stayed on at Dartmouth for seven years, he felt a certain compassion for those unfortunates who were permitted only four years in Hanover. For the truly disadvantaged who never even matriculated, he probably retained a hope for ultimate salvation through some later supernatural dispensation. Asked once by a heathen friend whether it had ever occurred to him that alumni of other institutions might feel the same loyalty toward their own colleges, Father replied with an incredulous and ingenuous "No."

Until he died in 1954, he kept in touch with every member of his Class. Family trips were likely to follow tortured, circuitous routs, to allow for visits with Dartmouth friends; as often as possible, they were engineered to include detours through Hanover. As we drove up the hill from West Lebanon, ten years of lines dropped from my father's face: the rejuvenating effect of Hanover on the faithful had set in.

My mother was a patient and understanding woman, who accepted the fact that she married the College when she married my father. Brought to Hanover first on her wedding trip, she returned the last time to see her grandson, Robert H. Ross III, graduate in June. She enjoyed a pleasant camaraderieand conceivably shared a few complaintswith wives of other '01s. It was not until the 50th reunion that she abandoned the austerity of dormitory accommodations for the comfort of the Hanover Inn. She acquiesced gracefully in the budgetary priority of the Alumni Fund, the early indoctrination of her children, and the assumption that Dartmouth men and their wives were ipso facto the most congenial companions. Although not of a Dartmouth family, she overcame this inherent disability to become the exemplary Dartmouth wife.

This indoctrination of the young, comparable to the early training of other natural aristocracies, is a sine qua non of the Dartmouth syndrome, to which the conscientious alumnus devotes considerable time and attention. A Dartmouth daughter is the ideal collaborator; a neutral and well-disciplined spouse is next best. A wife encumbered with heretical family alliances with lesser institutions may present a problem. Football games, reunions, and glamorous winter holidays in Han-over — the last particularly effective for city-bred childrenare all part of the regimen. Where other children start their musical careers chirping Mother Goose rhymes, Dartmouth young are drilled on The Winter Song and Eleazar Wheelock. If the offspring in question has the misfortune of being female, the methods obviously must vary, but similar care is demanded — that the line be continued, even under another name. The daughter must be protected at all costs from marrying out of the faith.

My own first conscious recollection of this process is of a February trip to Hanover at the age of three, although subtle subliminal conditioning had undoubtedly preceded it. My parents occupied Room 101 of the old Inn, the tower room directly over the gift shop, while I slept in a small adjoining room overlooking the Green, a splendid vantage point for people-watching. It was on the Green and on that visit that I was first introduced to skis, an encounter I have repeated rarely, but with uniformly disastrous results.

It was on that visit too that we came close to what might be considered the ultimate privilege, spending our last days in Hanover. When Father proposed a horse and sleigh as suitable conveyance for a visit to an old friend in Hartford, Vermont, my mother's reaction was realistic terror; my own, wild excitement. Though born and raised in Brooklyn, he was confident that his North Country heritage guaranteed his "being versed in country things." But he didn't know New Hampshire horses. The Hanover Livery Stable delivered a wild-eyed mare under the Inn portico on that frigid morning, and two men, ominously, held her head while we were immersed in voluminous fur robes. Unleashed, the creature bolted down West Wheelock Street and through the old bridge, with Father gamely tugging at the reins in a futile attempt to keep the pace within village speed limits. She settled down somewhat as we reached the rise and then level ground on the Vermont side, and we had a briefly idyllie, Christmas-candy kind of ride, sleigh bells jingling and all the rest, until we came to the steep winding hill down into Hartford. "Catapult" is the only word for our pell-mell descent into the village. We careened into the target dooryard and came to an abrupt halt in front of the barn. It was an act of supreme faith, my mother's making the return trip; only the circumstance that the last lap to the stable was uphill brought us back to Hanover intact.

SINCE females were even less likely in 1936 than in 1968 to be permitted to disturb the monastic life of the College, there was nothing for it but for me to be sent to school somewhere within reasonable distance of Hanover, close enough to facilitate meeting the right kind of man, but not close enough for distraction from the "business of learning." The Connecticut Valley was, almost by definition, the best location for a college, and the 113.6 miles from Russell Sage Hall to Cushing House at Smith proved in due course to be precisely the right distance.

My husband was as enthusiastic an undergraduate as the next man, but his loyalty to Dartmouth, and probably to me, must have been severely strained by frequent exposure to Father's tales of the old days in Hanover. He learned to count on a minimum of half an hour before a date to examine the '01 cane and hear, once again, of the eloquence of President Tucker, the glories of Matt Bullock's prowess on the football field, and the intellectual and physical rigors of a Dartmouth education at the turn of the century.

The 1938 Commencement was a comparatively tranquil affair, deceptively so, as hindsight was shortly to show us. It was less than three months before Munich, but the significance of the chaos in Europe hadn't fully penetrated the American campus. It is ironic to consider in 1968 that the graduating seniors were being urged toward greater involvement — activism, if you will. In his Valedictory to the class, President Ernest Martin Hopkins warned of "... the misfortune in America today, that in what has been our abundance of resources, and in the comforts which have been ours without parallel elsewhere, and in the freedom from effort which has been extended to us as compared with candidates of earlier days, we have slipped into passiveness, and we have lost the zest for battle against degeneration in our individual or collective lives, and we have gone our way forgetting what manner of men we are." He concluded with the appeal, "Men of 1938 - may such forgetfulness never be yours." If the men of '38 were tempted by such forgetfulness, they were soon to be brought harshly to recollection. The great majority of them served in the armed forces; 14 of them lost their lives in World War II.

We were married in the summer of 1940 in what might be the prototype of Dartmouth weddings. The minister of the small village church in Maine was Wilbur Bull '09, D.D. '40; the groom, best man, and all the ushers, with the exception of one ringer from Vanderbilt, were '38. Davis (Stoney) Jackson '36 coaxed astonishing melody from a wheezy old organ, weaving variations on Dartmouth Undying, unobtrusively but unmistakably, into the prelude. The father of the bride probably found the storied compensation for losing a daughter more comforting in that he was gaining a Dartmouth son-in-law.

The first stop on our wedding trip was, quite predictably, the Hanover Inn. As we waited for dinner on the Terrace, my husband introduced me to Dean Lloyd K. Neidlinger, who was the first person, aside from those at the wedding, to call me "Mrs. Ross." Resigned to the inexorable omnipresence of Dartmouth College in my life, I might almost construe the encounter as quasi-official sanction of the match, third only to that of God and the State of Maine, conferred earlier in the day. With such. sponsorship, how could a marriage fail?

Only the war years have interrupted our periodic returns to Hanover, of late for the entire summer. Reunions have been indispensable, of course; any other pretext for going back was welcome — or, on occasion, invented. In spite of the geographic obstacles of residence in faraway places, our children have come to find Hanover as familiar as the next town up the pike. My husband, an English professor whose commitment to teaching and the liberal arts traces its origin to the influence of such men as Brooks Henderson, Franklin McDuffee, and David Lambuth, now gone, and Arthur Wilson, Cudworth Flint, and John Hurd, finds the familiar and hospitable stacks of Baker Library the ideal place to pursue his scholarly research during the summer months.

We were proud in June of a son and of his class, which seems to demonstrate abundantly that concern for "competence, conscience, capacity for commitment, and comprehensive awareness" which President Dickey has characterized as "the institutional purpose of a college." One need not endorse the individual response to respect the collective concern or the pervasive anxiety to find new solutions for ancient ills. We felt renewed pride too in the College for maintaining the intellectual climate where free men can express freely and peacefully their honest convictions, conventional or unorthodox.

So now we have lost an undergraduate and added a new cane to the family collection - and another set of class notes to read and another group of men to take pride in. And my membership in the Dartmouth Auxiliary has taken on a new dimension.

There are, to be sure, both joys and tribulations to this association. The former, as any good Dartmouth man will be happy to tell you, are self-evident; the latter, as his wife can testify, are undeniable, though relatively minor in the long run. It takes a stalwart woman to survive continual contact with the more excessive manifestations of the Dartmouth religion. Like other zealots, its adherents have been known to display a singular intolerance for other creeds and a pious asumption of superiority. Let's face it: at their worst, the faithful congregated can be sanctimonious, irrationally partisan, and long-winded to the point of tedium. To the novice in the Auxiliary, one can only offer sympathy and counsel patience. Indeed, even the old hand, despite a certain immunity acquired from long exposure, blanches occasionally at the thickness of the Big Green icing.

But we might as well bear with them; the tribal rites are inescapable adjuncts to the Dartmouth fellowship. If a new hat must be sacrificed to class standing in the Green Derby, it's a small price. If one privately considers her husband's sophomore sidekick a crashing boreor Han-over something less than the perfect place to spend a dreary November weekend it's best not to challenge the point. The compensations are many. They all have to do with what "manner of men" your Sons of Eleazar are.

As for me, I'm already packing for 1938's delayed 30th reunion. And after that, we'll be house-hunting around Hanover. Where else would one retire?

A happy continuum.

The author is the wife of Robert H. Ross '38, Professor of English at Washington State University, in Pullman, and the mother of Robert H. Ross III '68. Her father was the late Dr. Eliot Bishop '01.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

February 1969 By Susan Liddicoat -

Feature

FeatureA Call for Equal Opportunity

February 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Student View of the Crisis, 1816-19

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

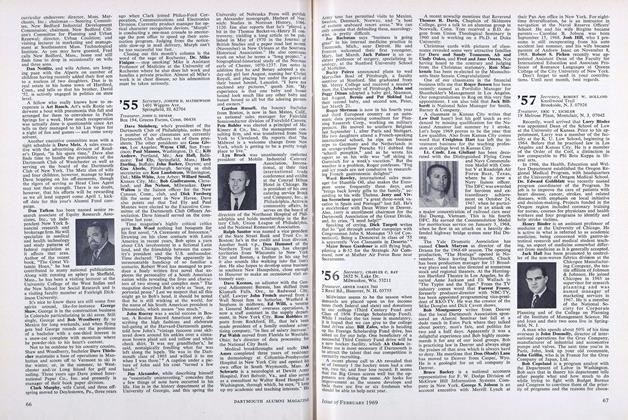

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

February 1969 By JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON, JOHN G. DEMAS