By Bevan M. French'58 and Nicholas M. Short, editors. Baltimore: Mono Book Corp., 1968. 644 pp.$18.

Photographs from both manned and unmanned space vehicles have made it abundantly clear, during the past decade, that the moon's surface is peppered with thousands of meteoritic impact craters ranging in size from those hundreds of miles across to those barely discernible in close-up television photos. It would be strange, indeed, if the Earth had escaped this extra-terrestrial bombardment now so obvious on its satellite's surface, and of course it has not. An educated guess is that there have been at least a million crater-forming impacts on the Earth's surface, or an average of one per 4500 years throughout its long history.

The lack of an atmosphere on the moon has allowed its impact scars to be preserved, but the combination of a restless crust and weathering has blurred the record on the Earth's surface to such an extent that it was not until 1907 that Meteor Crater, Ariz., was seriously regarded as a probable example of an impact scar. By 1925, there were only additional examples, but the list now Two crown to 50 or 100, largely on the basis of intensified investigations during the past decade There is not much doubt that this list will eventually be expanded several times It's reassuring, perhaps, to know that Science is right, even if it is now certain that catastrophe can never be very far away.

The poor topographic expression of most impact craters on the Earth means that subtle methods must be used for identification, but the question is, how? To answer this question French and Short organized a conference in behalf of NASA at Greenbelt, Md., on April 14-16, 1968. The present volume an outgrowth of that meeting, is directed largely to a consideration of the effects that the extremely high pressures and temperatures resulting from meteorite impact will produce in rocks and minerals. Papers presented at the conference are organized into sections dealing first with the results of laboratory experiments, progressing next to a consideration of cratering mechanics and finally passing on to a detailed description of the features observable in well - recognized meteoritic craters and in the relatively small craters produced by nuclear explosions. Shock metamorphism is the Rosetta stone that ties all these features together and proves to be the decisive key for locating the sites of the awesome collisions that have plagued the Earth since its beginning.

Dr. French is one of the leaders in a branch of the geological sciences that was unknown a few short years ago. In addition to his careful editorship, this volume bears his stamp through two excellent papers, one of them a perceptive introductory review and the other a provocative contribution detailing the almost irrefutable evidence that the world's largest nickel deposit at Sudbury, Ontario, started its geological development as an impact crater 40 miles in diameter. This is pretty heady stuff and a clue to the type of imaginative deduction that characterizes several of the 43 papers in Shock Metamorphism. There's still an excitement and challenge in uncovering the past.

Mr. Lyons is Professor of Geology, Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

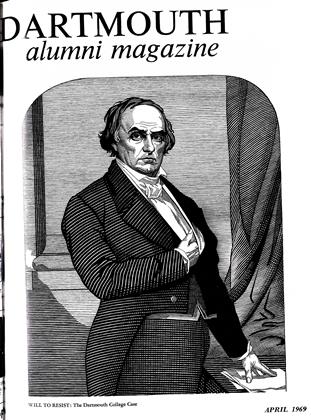

FeatureWILL TO RESIST

April 1969 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Feature

FeatureThe New Dean of the College...

April 1969 -

Feature

FeatureCongress Authorizes National Medal

April 1969 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

April 1969 By ERNEST S. DAVIS JR., WESLEY H. BEATTIE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

April 1969 By CHARLES V. RAYMOND, G. WARREN FRENCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

April 1969 By JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON, RANDOLPH J. HAYES

JOHN B. LYONS

-

Books

BooksCONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GEOLOGY OF URANIUM AND THORIUM:

October 1956 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksPRINCIPLES OF GEO CHEMICAL PROSPECTING.

November 1957 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksGEOCHEMISTRY OF BERYLLIUM AND GENETIC TYPES OF BERYLLIUM DEPOSITS.

OCTOBER 1966 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksLunar Light

JAN./FEB. 1978 By JOHN B. LYONS