By Budd Schulberg '36.New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc.,1972. 158 pp. $5.95.

The morning after the Frazier-Ali Fight of the Century, the loser philosophized to Budd Schulberg about his first defeat in 31 starts: "A plane crashes. A President gets assassinated. A civil rights leader assassinated. People forget in two weeks. Old news."

Muhammad Ali, a.k.a. Cassius Clay until he shucked his "slave name" in 1966 after beating Sonny Liston for the title, was right. His loss to Frazier on March 8, 1971 is old news now. It was already old that same month, when Schulberg began writing this book—on assignment from Playboy, whose editors wanted a scant 4,000 words for delivery in May and who regretfully declined when offered 60,000 in September, instead.

But there was an Ali-like method in Budd's "madness." Because this book that began as a magazine article about the most widely publicized prizefight in the 4,000-year history of The Manly Art is something else entirely: a lyrical, informed, and impassioned analysis of the sociology of professional boxing—coupled, like one of Ali's own lethal "combinations," with an eye-opening in-depth study of the most controversial superstar of our time. Wisely, Budd accords The Fight that made Frazier undisputed world champion only eight pages (one reason, among many, for the astonishing vividness of his reportage). The 140 pages preceding, and the ten that follow, tell a story that was brand-new to this reader. And unsettling. Like the "mythopeic Muhammad," it stings again and again with the shock of discovery.

Schulberg posits a "theory about the heavyweight championship": that "somehow each of the great figures to hold the title manages to sum the spirit of his time." Doing some "roadwork through history," he follows the trail from the "Jew Champion," Daniel Mendoza, who took the title from Richard Humphries in 1789 by inventing the concept of footwork, to the first black-white confrontation in the ring (Molineaux v. Cribb, 1810), to the Irish-American champions at the turn of the present century, ending with Jim Jeffries, whom Schulberg sees as "the simple white boilermaker of 1905," as his conqueror, Jack Johnson, was "the upstart 'bad nigger of 1910'." Then there was Jack Dempsey, epitomizing "the Twenties of vigorous flamboyance," while his cool-and-careful successor, Gene Tunney, was "the right man for the right time ... Coolidge-and-Hoover time, [when] the economy was fundamentally sound." When the economy soured—

The face of America was forever changed, a society that had reared itself on rugged individualism became a welfare state. Naturally we needed a new breed of heavyweight champion and 10, he materialized ...

In the person of the Brown Bomber, Joe Louis—who, in Schulberg's opinion, was "simply the greatest heavyweight fighter who ever lived." Budd's description of Joe's 124-second annihilation of Max Schmeling in their second, Nazi-blessed meeting, and of the Victory Night that followed, is a classic of reportage.

But there are light-years of difference, this book makes clear (meticulously explaining why), between "brown" Joe Louis, who was offered and accepted a sergeantcy in our WWII Army while lesser white athletes were granted commissions, and Muhammad Ali, who declined induction on religious grounds after stating, the year before, "I don't have nothin' against them Viet Congs. They never called me nigger." Schulberg, noting that Ali assigns 50% of his earnings to his manager, Herbert Muhammad, son of the Muslims' prophet Elijah, sees the 1960 Olympic gold-medallist as "the most mental as well as the most politically conscious of all our champions"—a man in the charismatic, liberationist tradition of Marcus Garvey, W.E. DuBois, and Jomo Kenyatta—"a black Johnny Appleseed, in pursuit of a buck and in pursuit of the truth."

Schulberg is no apologist for Ali. But months of intimate association—from the first comeback fight against Quarry in Maddox's Georgia to the title fight in Madison Square Garden—have convinced him that the "black butterfly-bee" is more than an athletic phenomenon: he is an authentic spokesman for millions upon millions of black Americans ("I use fighting as a platform ... to get to my people"), and perhaps for many of their brown, yellow, and white brothers—here and elsewhere. Budd sums it this way:

From the somewhat narrow base of Black Muslimism that puts off black leaders from moderate to radical ... Muhammad Ali has [developed] the ecumenical qualities of gregariousness, disingenuousness, a chameleonic sincerity, an innate shamanism that endows him with the gift of tongues and appoints him soothsayer, sideshow barker, and seer.

That is why Loser and Still Champion:Muhammad A li seems such an apt title. And why it merits the attention not only of sportsbuffs but of every serious student of the century that began at Dienbienphu.

Mr. Silverman, class secretary for 1934, is awriter well known since 1935 in radio, films,and television.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1972

July 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

July 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

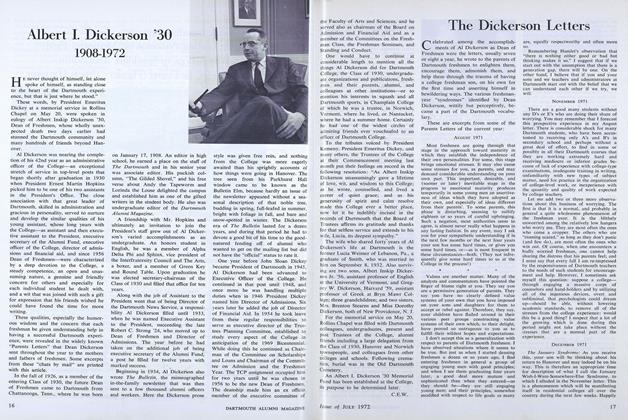

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

July 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

July 1972

STANLEY H. SILVERMAN '34

Books

-

Books

Books"The Loco-Weed Disease,"

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Books

BooksEFFECTIVE USE OF BUSINESS CONSULTANTS.

JANUARY 1964 By ALVAR O. ELBING JR. -

Books

BooksTHE IDEAL BOOK

May 1936 By Herbert F. West -

Books

BooksA Bishop's Message

February 1918 By J. L. M. -

Books

BooksA CRITICAL INTRODUCTION TO ETHICS,

April 1949 By Maurice Mandelbaum '29. -

Books

BooksTHE GRAVEYARD NEVER CLOSES

May 1941 By Oliver L. Lilley '30