SINAI:The Great and Terrible Wildernessby Burton Bernstein '53 Viking, 1979. 268 pp. $13.95

Stand on many of the world's great battlefields and the museum tranquillity there may propose comforting contrasts with the past. The Sinai peninsula, though invaded at the least 50 times in recorded history allows of no such comfort. Minefields remain, and soldiers aplenty, and everywhere there is the fear, sometimes the hope, that the Sinai will be a battlefield again.

Burton Bernstein's book on this problematic triangle is the result of four trips into the Sinai in 1978, on assignment for The New Yorker. All aspects of the place fascinate him history, geography, inhabitants but the Yom Kippur war, and the Sadat initiative, and the Camp David agreements repeatedly force themselves to the fore. This is a book on all-too-current affairs, and its excursions into history and anthropology are delightful moments stolen from the business of politics.

In fulfilling a vow or rather a "solemn, self-indulgent promise of adventure" made in 1969 to "get some intimate sense of the land and people" of the Sinai, Bernstein rather remarkably put as much emphasis on people as on land. He comments that "Deserts, any deserts, fascinate," but he is as fascinated by the fact that this desert is peopled. He undertakes to show that the Bedouin of the Sinai are not the negligible non-persons that all the parties to wars and treaties silently assume them to be. For a journalist, without Arabic and with only a few days to spend in the country, to succeed in this ambition required unusual assistance and unusual luck in finding it. They came to Bernstein in the form of Dr. Clinton Bailey, lecturer in Bedouin Studies at Tel Aviv University, speaker of Hebrew and Arabic, the best, and, one concludes, for the purposes of this book, the only possible guide to the Sinai. Coincidentally, but one hopes not merely coincidentally, Bailey spent his freshman year at Dartmouth while Bernstein was a senior here.

Bailey introduced Bernstein to the lives of the Sinai Bedouin, providing facts on their history, customs, poetry, economy, and most revealingly their psychology. Since Bailey was apparently the honored friend of almost every Bedouin they met, Bernstein was able to see at close quarters the homes and families of a cross-section of this people, making them the human backdrop to his visits with Israeli settlers and soldiers, the monks of St. Catherine's monastery (ill-tempered and besieged by tourists; St. Catherine's is apparently a tough station, something of a punishment for Greek Orthodox monks), Finnish, Swedish, Ghanaian soldiers of the U.N. Disengagement Observer Force, and the Americans of the Sinai Field Mission, a "transplanted chunk of Texas," its base a prefabricated Holiday Inn diverted from Florida.

When Bernstein made his climbs to the great Sinai historical sites, Mount Sinai or the turquoise mines of Serabit El Khadim (where the hieroglyphs of the Egyptians can be seen in inscriptions being transformed into an infinitely re-combinable phonetic script, "the democratization of literacy"), he was guided by Bedouins. His sub-title from Deuteronomy does not really reflect the emotional truth of his book, for he chiefly sees "the great and terrible wilderness" through the eyes of the Bedouin, for whom it is simply home. For peace, "the Sinai was the keystone and the key.... And if, for once, the indigenous people of a newly developed land could simply be left alone to live their lives as they saw fit... the humanitarian precedent would be a telling example to the world." May it be so, but development means occupation, however benevolent, and, as Bernstein says elsewhere, "If there is a curse on the Sinai Bedouin, it is the curse of occupation."

David Wykes is associate professor and vice-chairman of Dartmouth's Department of English.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

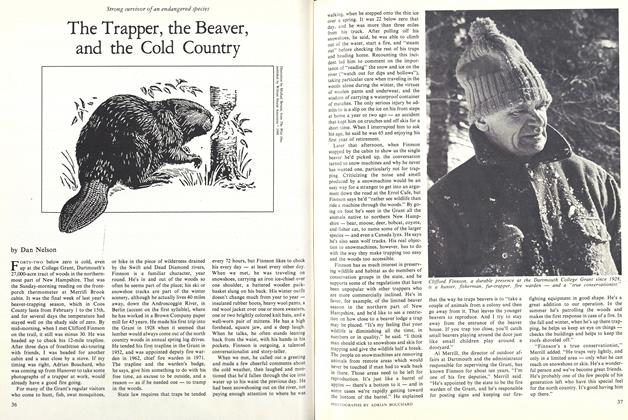

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

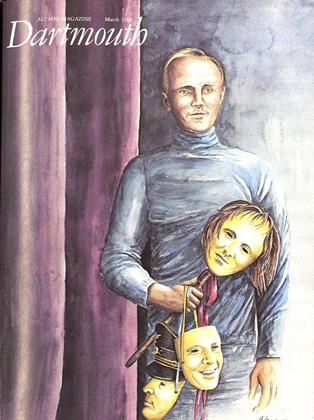

Cover Story

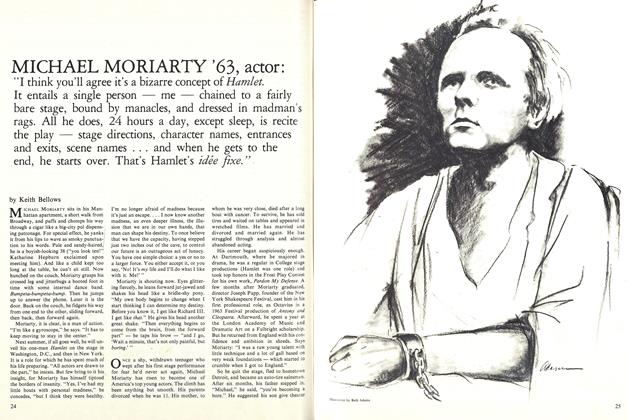

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

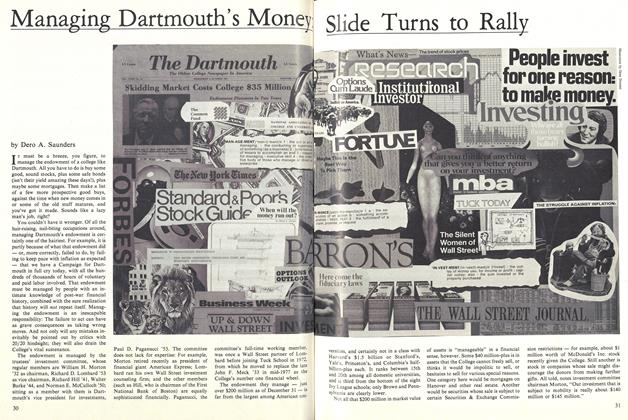

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

David Wykes

Books

-

Books

BooksCharles H. Richardson '92, and James E. Maynard are the authors

June 1933 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MAY 1967 -

Books

BooksTHE ISLANDS

June 1936 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksSUBMARINE! THE STORY OF UNDERSEA FIGHTERS

January 1943 By Bernard Brodie -

Books

BooksTHE "DESERT RATS" MUSICAL SHORTHAND SYSTEM

December 1935 By D.E. Cobleigh '23 -

Books

BooksLIQUIDITY AND STABILITY

January 1941 By Ray V. Leffler