By Evan S. Connell Jr. '45.New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969. 369pp. $5.95.

It is difficult to place within a tradition of post-World War II fiction Connell's lucid, austere, ironic, and "cumulative mosaic" style. Author of four novels and three other books including an epic poem, Notes froma Bottle Found on the Beach at Carmel, he in his latest novel writes a genuine, often elegaic chronicle of a Kansas City businessman, Mr. Bridge. Here we can discover curious counterpoints to "Portnoy's complaints," Moses Elkanah Herzog's epistolary introspections, and recent fiction's ubiquitous Jewish mothers. For Walter G. Bridge is an archetypal Midwestern White Anglo-Saxon Protestant who commutes in the Puritan-industrious Depression to his late 1930's office and returns each night to his inventoried suburban haven with a hedge. Outwardly as simple as Connell's surgicallypared prose, Walter Bridge slowly discovers his obsessive and complex rituals of economic pragmatism to be foundering and obsolete.

At the outbreak of Hitler's invasion of Poland, Walter and Ruth (heroine of Connell's companion-piece, Mrs. Bridge, published in 1959) hastily head home on a French tourist liner. On the mid-Atlantic they grope for each other's hands as they sit in deck chairs on a night as dark as the moon's nether landscape. Ruth Bridge weeps; her husband, ever anxious at emotional effusions, hears her blow her nose and sigh.

"Everything has been just lovely," she said.

She had been crying from happiness, which was something he had never done in his life and which was incomprehensible to him. Thoughtfully, he contemplated the fearful blackness surrounding them, for there was no light anywhere beyond the rail of the ship, and he wondered if this was how it must be, if this was how they would end their lives, accompanying each other so closely, loving each other, touching one another with affection and sympathy, yet singularly alone.

The novel builds to such discovery: Walter Bridge's daily existential triumphs and absurdities, renewed zeal in middle age to mask or bury the missing "Something"; his morbid fear of change; his hatred of Roosevelt and "communists in the Labor Department"; his pride in his talented adolescent son, Douglas, who has his father's unmistakable obstinacy; his inability to explain to his daughter Caroline why rabbits die from terror when a dog attacks her Easter bunny; his economics lecture to the loyal black maid, Harriet, and refusal of a $25 advance on her wages to protect her lover from loan-sharks.

Connell creates with F. Scott Fitzgerald's Midwestern sympathy and sadness; his people reveal themselves, unaided by stylistic legerdemain. He develops in Walter Bridge a more genuine, perplexed George F. Babbitt - with none of Sinclair Lewis's envious indulgences and heavy-handed ironies. His episodes remind one of the most acute passages in Mary McCarthy's short stories, but without her Freudian venom and denigration. Connell's penetrating, compassionate, and yet fiercely critical perspective furnish us (whether we are kinsmen to Portnoy or American bread-basket WASP's) with a family's arduous hopes, grinding travails, and forfeited opportunities for human growth and exercise of charity, amid the fervent, evangelical rationale of "free enterprise." All this he tells without John O'Hara' compulsive tears and highballs or John Updike's libidinous exhibitionism. In Evan Connell, the Nixonian "forgotten majority" of Americans have found their most knowledgeable, eloquent, and controlled satiric historian.

Mr. White has taught English at RutgersUniversity and Bates College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

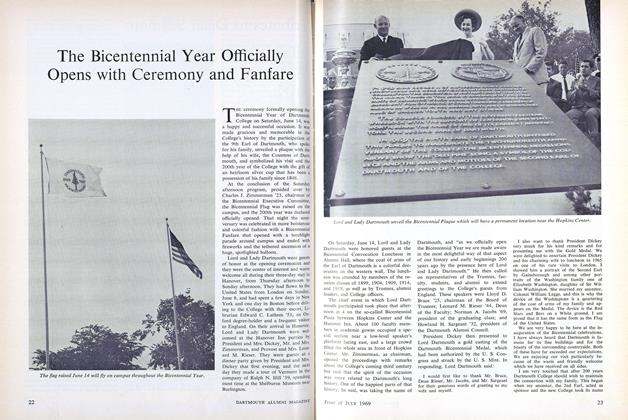

FeatureThe Bicentennial Year Officially Opens with Ceremony and Fanfare

July 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe 50-Year Address

July 1969 By DR. ROBERT M. STECHER '19 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1969

July 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1969 By KENNETH IRA PAUL '69 -

Feature

FeatureA New Investment Concept: Total Return

July 1969 By JOHN F. MECK '33 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1969

ROBERT O. WHITE '54

Books

-

Books

BooksA SURVEY OF RESEARCH IN THE FIELD OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS

June 1929 -

Books

Books"The Loco-Weed Disease,"

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Books

BooksSHAKSPERE, SHAKESPEARE AND

April 1938 By Anton A. Raven. -

Books

BooksLake Unlocked

SEPT. 1977 By CHARLES T. MORRISSEY '56 -

Books

BooksEARLY ENGLISH CHURCHES IN AMERICA

November 1952 By ROY B. CHAMBERLIN -

Books

BooksAMERICAN SHIPS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58