With 15 Indian freshmen plus eight others, Dartmouth now has the largest Indian enrollment in its history

Dartmouth College is embarking this fall on a unique Indian program designed to bring to fruition a dream envisioned 200 years ago.

As the College began its 201st academic year on September 24, the largest number of Indian American students ever to enroll here at one time matriculated with the Class of 1974.

Founded by the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock under a Royal Charter from the King of England for the “Education and Instruction of Youth of the Indian tribes in this Land . . . English youth and any others,” Dartmouth has never really realized the first and, to Eleazar, foremost element of that dream. As part of the College’s commitment to educational opportunity for disadvantaged minorities, however, President John Kemeny set about early in his administration to realize this historic mission.

“Though the College he founded in 1769 has prospered,” President Kemeny says, “only a part of Eleazar’s dream has come true. Because I believe deeply in Eleazar’s vision, I pledge my energies to the effort of translating the long-de- ferred promise of Dartmouth’s charter into reality.”

President Kemeny chose the Bicen- tennial anniversary as an especially ap- propriate time to place new emphasis on the education and instruction of the Indian American, adding, “We’re quite excited about the program and our alumni seem very attached to the idea.”

President Kemeny wasted no time in announcing a major recommitment to the College’s original purpose. Less than a week after his selection last January as the 13th President in the Wheelock Succession he said he hoped at least 15 Indian American students could be enrolled each year for the next four years.

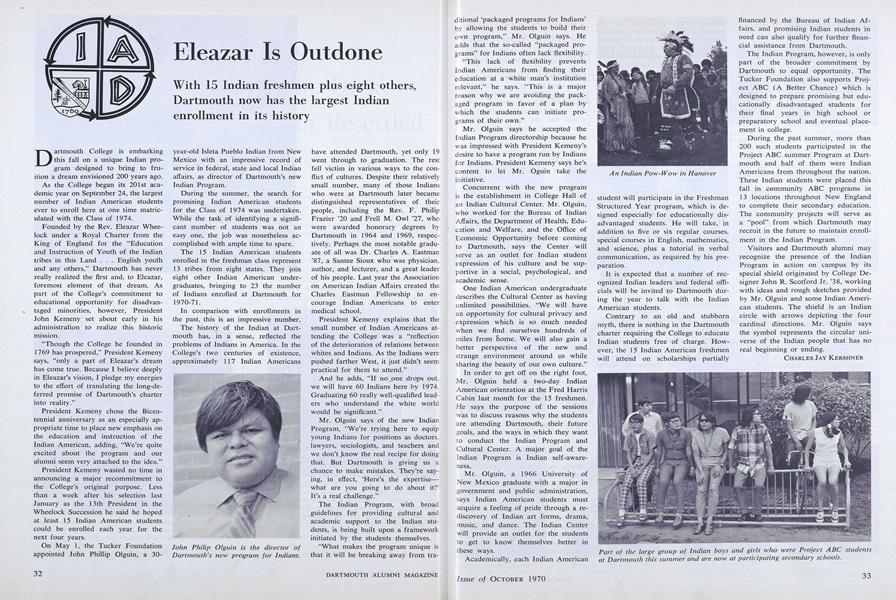

On May 1, the Tucker Foundation appointed John Phillip Olguin, a 30- year-old Isleta Pueblo Indian from New Mexico with an impressive record of service in federal, state and local Indian affairs, as director of Dartmouth’s new Indian Program.

During the summer, the search for promising Indian American students for the Class of 1974 was undertaken. While the task of identifying a signifi- cant number of students was not an easy one, the job was nonetheless ac- complished with ample time to spare.

The 15 Indian American students enrolled in the freshman class represent 13 tribes from eight states. They join eight other Indian American under- graduates, bringing to 23 the number of Indians enrolled at Dartmouth for 1970-71.

In comparison with enrollments in the past, this is an impressive number.

The history of the Indian at Dart- mouth has, in a sense, reflected the problems of Indians in America. In the College’s two centuries of existence, approximately 117 Indian Americans have attended Dartmouth, yet only 19 went through to graduation. The rest fell victim in various ways to the con- flict of cultures. Despite their relatively small number, many of those Indians who were at Dartmouth later became distinguished representatives of their people, including the Rev. F. Philip Frazier ’2O and Frell M. Owl ’27, who were awarded honorary degrees by Dartmouth in 1964 and 1969, respec- tively. Perhaps the most notable gradu- ate of all was Dr. Charles A. Eastman ’B7, a Santee Sioux who was physician, author, and lecturer, and a great leader of his people. Last year the Association on American Indian Affairs created the Charles Eastman Fellowship to en- courage Indian Americans to enter medical school.

President Keraeny explains that the small number of Indian Americans at- tending the College was a “reflection of the deterioration of relations between whites and Indians. As the Indians were pushed farther West, it just didn’t seem practical for them to attend.”

And he adds, “If no one drops out, we will have 60 Indians here by 1974. Graduating 60 really well-qualified lead- ers who understand the white world would be significant.”

Mr. Olguin says of the new Indian Program, “We’re trying here to equip young Indians for positions as doctors, lawyers, sociologists, and teachers and we don’t know the real recipe for doing that. But Dartmouth is giving us a chance to make mistakes. They’re say- ing, in effect, ‘Here’s the expertise— what are you going to do about it?’ It’s a real challenge.”

The Indian Program, with broad guidelines for providing cultural and academic support to the Indian stu- dents, is being built upon a framework initiated by the students themselves. “What makes the program unique is that it will be breaking away from tra- ditional ‘packaged programs for Indians’ by allowing the students to build their own program,” Mr. Olguin says. He adds that the so-called “packaged pro- grams” for Indians often lack flexibility.

“This lack of flexibility prevents Indian Americans from finding their education at a white man’s institution relevant,” he says. “This is a major reason why we are avoiding the pack- aged program in favor of a plan by which the students can initiate pro- grams of their own.”

Mr. Olguin says he accepted the Indian Program directorship because he was impressed with President Kemeny’s desire to have a program run by Indians for Indians. President Kemeny says he’s content to let Mr. Oguin take the initiative.

Concurrent with the new program is the establishment in College Hall of an Indian Cultural Center. Mr. Olguin, who worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Department of Health, Edu- cation and Welfare, and the Office of Economic Opportunity before coming to Dartmouth, says the Center will serve as an outlet for Indian student expression of his culture and be sup- portive in a social, psychological, and academic sense.

One Indian American undergraduate describes the Cultural Center as having unlimited possibilities. “We will have an opportunity for cultural privacy and expression which is so much needed when we find ourselves hundreds of miles from home. We will also gain a better perspective of the new and strange environment around us while sharing the beauty of our own culture.”

In order to get off on the right foot, Mr. Olguin held a two-day Indian American orientation at the Fred Harris Cabin last month for the 15 freshmen. He says the purpose of the sessions was to discuss reasons why the students are attending Dartmouth, their future goals, and the ways in which they want to conduct the Indian Program and Cultural Center. A major goal of the Indian Program is Indian self-aware- ness.

Mr. Olguin, a 1966 University of New Mexico graduate with a major in government and public administration, says Indian American students must acquire a feeling of pride through a re- discovery of Indian art forms, drama, music, and dance. The Indian Center will provide an outlet for the students to get to know themselves better in these ways.

Academically, each Indian American student will participate in the Freshman Structured Year program, which is de- signed especially for educationally dis- advantaged students. He will take, in addition to five or six regular courses, special courses in English, mathematics, and science, plus a tutorial in verbal communication, as required by his pre- paration.

It is expected that a number of rec- ognized Indian leaders and federal offi- cials will be invited to Dartmouth dur- ing the year to talk with the Indian American students.

Contrary to an old and stubborn myth, there is nothing in the Dartmouth charter requiring the College to educate Indian students free of charge. How- ever, the 15 Indian American freshmen will attend on scholarships partially financed by the Bureau of Indian Af- fairs, and promising Indian students in need can also qualify for further finan- cial assistance from Dartmouth.

The Indian Program, however, is only part of the broader commitment by Dartmouth to equal opportunity. The Tucker Foundation also supports Proj- ect ABC (A Better Chance) which is designed to prepare promising but edu- cationally disadvantaged students for their final years in high school or preparatory school and eventual place- ment in college.

During the past summer, more than 200 such students participated in the Project ABC summer Program at Dart- mouth and half of them were Indian Americans from throughout the nation. These Indian students were placed this fall in community ABC programs in 13 locations throughout New England to complete their secondary education. The community projects will serve as a “pool” from which Dartmouth may recruit in the future to maintain enroll- ment in the Indian Program.

Visitors and Dartmouth alumni may recognize the presence of the Indian Program in action on campus by its special shield originated by College De- signer John R. Scotford Jr. ’3B, working with ideas and rough sketches provided by Mr. Olguin and some Indian Ameri- can students. The shield is an Indian circle with arrows depicting the four cardinal directions. Mr. Olguin says the symbol represents the circular uni- verse of the Indian people that has no real beginning or ending.

John Philip Olguin is the director ofDartmouth’s new program for Indians.

An Indian Pow-Wow in Hanover

Part of the large group of Indian boys and girls who were Project ABC studentsat Dartmouth this summer and are now at participating secondary schools.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLiberating the Ph.D.

October 1970 By Robert B. Graham ’40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dickeys Get Resettled

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleDear Mr. Cunningham . . .

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1970 By William R. Meyer -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

October 1970 By Jack DeGange -

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

October 1970 By JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON, JOHN G. DEMAS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Great Editor Remembered

October 1951 -

Cover Story

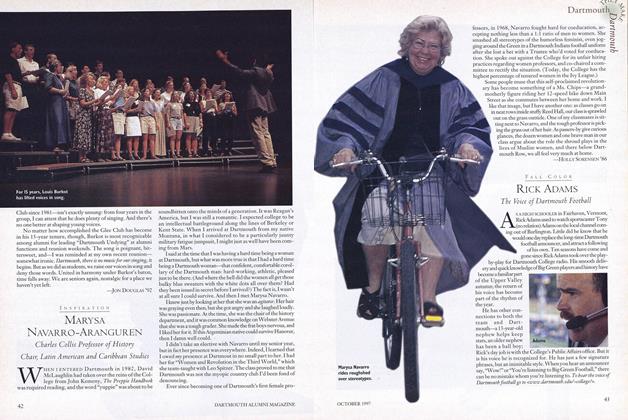

Cover StoryRick Adams

OCTOBER 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

APRIL 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryANDREW WEIBRECHT '09

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND HISTORY

FEBRUARY 1963 By LOUIS MORTON -

Feature

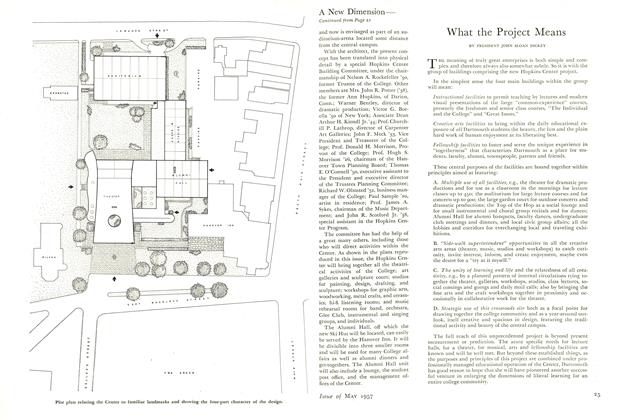

FeatureWhat the Project Means

MAY 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY