DIRECTOR, HOPKINS CENTER DESIGN WORKSHOPS

If the liberal arts ideal is the Renaissance Man, its spectre is the dilettante, whom Whitehead called "a merely well-informed young man . . . the greatest bore on God's earth." When President Hopkins established the Design Workshops in 1941, it was with the conviction that Dartmouth should educate productive individuals, for "although it is the responsibility of the liberal arts to elevate the mind, it is not disembodied intellect."

With Renaissance personalities harder to find in the current academic environment of increasing specialization, the study of design offers students an experience that demands not only the mind, but also the eye and the hand. The College's Design Workshops share with other Hopkins Center programs the nurturing and education of makers and creators.

passive experience of attending a lecture, the first-hand experience of imagining a design and actually making it provides an exceptional basis for learning and discipline. As Peter Smith, director emeritus of the Hopkins Center, once put it, students learn and are often humbled by the realization that simple, everyday, taken-for-granted objects are not necessarily simple and are by no means to be taken for granted. They learn the value of precision, the rewards of discipline and patience, the desirability of planning ahead, the necessity of understanding one's material, and the realization that "measure twice and cut once" applies As an educational opportunity, the workshops provide an intimate, tutorial, unpressured environment in which students' ideas and initiatives are taken seriously. The instructors serve as guides, mentors, and collaborators in problem-solving. Unlike the to more in life than just sawing wood. The young Dartmouth alumni who have told me that they learned more in the workshops than in the classroom were not talking about the acquisition of information, but about two even more important commodities: knowing how to work well and knowing how to live well.

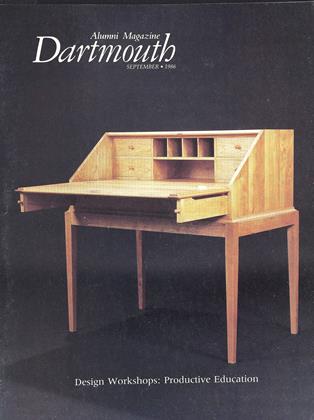

Successful design is not simply a matter of the application of so-called "design principles," as many believe, but rather depends on a complete mastery of the technical processes of a medium and on the ability to be resourceful and inventive. As a synthesis of form and function, design requires the sensitivity of an artist (form) and the technical knowledge of an engineer (function). At best, design is an intricate task involving integration of skills, imagination, and an understanding of human needs.

To understand the difficulty of the design task, consider the following statement from By Design: Why there areno locks on the bathroom doors in the HotelLouis XIV and other object lessons, a book by Ralph Caplan: "To design a chair without knowing how the body is designed would be like designing an egg carton without knowing how eggs are designed. But although probably no package designer would commit the latter error, chair designers customarily commit the former. And they get away with it, because human beings are more forgiving than eggs. An egg is powerless to compensate for bad design, and will simply break under the strain."

Chairs are so difficult that even Mies van der Rohe once said it was harder to design a great chair than a skyscraper. This admission not only says something about the difficulty of creating more with less, but also says that the same process that we use to design simple, everyday objects can be used to solve greater problems.

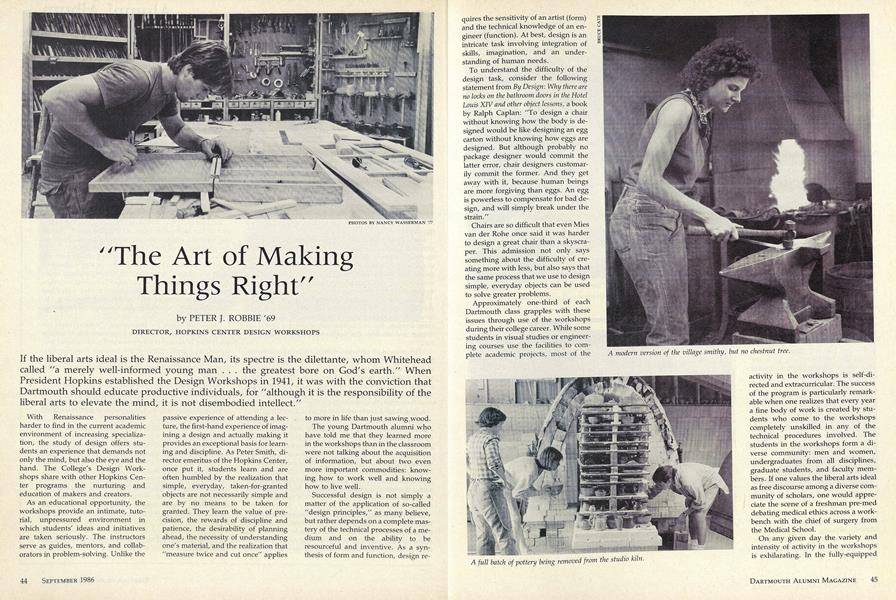

Approximately one-third of each Dartmouth class grapples with these issues through use of the workshops during their college career. While some students in visual studies or engineering courses use the facilities to complete academic projects, most of the activity in the workshops is self-directed and extracurricular. The success of the program is particularly remarkable when one realizes that every year a fine body of work is created by students who come to the workshops completely unskilled in any of the technical procedures involved. The students in the workshops form a diverse community: men and women, undergraduates from all disciplines, graduate students, and faculty members. If one values the liberal arts ideal as free discourse among a diverse community of scholars, one would appreciate the scene of a freshman pre-med debating medical ethics across a workbench with the chief of surgery from the Medical School.

On any given day the variety and intensity of activity in the workshops is exhilarating. In the fully-equipped woodworking shop lathes, planers, and saws are all buzzing while in progress are several pieces of furniture, a cedar-planked canoe, and an experimental cross-country ski. In the design library some students are browsing through illustrations of Shaker furniture and another is sketching the proportions of a desk that will accommodate his Macintosh computer. In the metal shop the blacksmith forge is blazing, and machine lathes and milling machine are being used to make precision parts. Students in a glassblowing class try to master the magic of making useful objects from molten glass, while in the Avril Foundry a sand mold is being prepared for a bronze casting. In the Clafin Jewelry Studio ten students, huddled over work benches, are filing, sawing, and polishing intricate pieces of jewelry of their own design. At the Davidson Pottery Studio, located in a brick cape down by Ledyard Bridge, pottery wheels are slowly humming while the daily pot of popcorn starts to crackle on top of the woodstove.

An awareness of all this activity happening simultaneously provides a sense of the unusual opportunities this program offers students interested in design. In well-equipped workshops staffed by experienced craftsmen, the students believe that they can learn to make virtually anything.

The author, who majored in English as anundergraduate at Dartmouth, went on toearn an M.F.A. from Cornell. A sculptor,he has also studied with stonecutters inItaly and taught sculpture and design as amember of the College's Department of Visualstudies faculty from 1973-1982. Hisown work has been shown in several exhibitions, including a one-man show atNew York's Acquavella Galleries. He hasbeen the director of the Design Workshopssince 1982.

A modern version of the village smithy, but no chestnut tree.

A full batch of pottery being removed from the studio kiln

Setting a precious stone in a ring is delicate work,

A mortise joint being created for a table leg,

Finish-sanding a table apron in the woodworking shop

A bicycle frame being made in the metalworking shop

Planing for the final fit of a chair slat.

Refining details of a piece of sculpture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLate Afternoon Thoughts On the Twentieth Century

September 1986 By LEWIS THOMAS -

Sports

SportsSports

September 1986 By Jim Needham '70 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

September 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Article

ArticleReady for Lift Off

September 1986 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Article

ArticleSandy Apgar '62 A books and mortar man

September 1986 By David K. Martin '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

September 1986 By Bruce D. jolly

Features

-

Feature

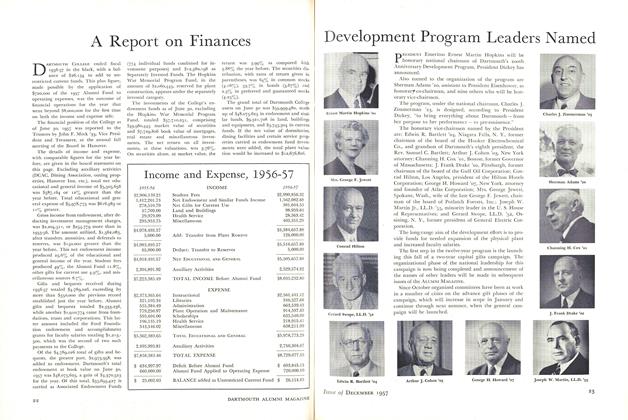

FeatureDevelopment Program Leaders Named

December 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe Magazine Has A Birthday

OCTOBER 1958 By C.E.W. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN AT LUGING

Sept/Oct 2001 By CAMERON MYLER '92 -

Feature

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

FEBRUARY 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Cover Story

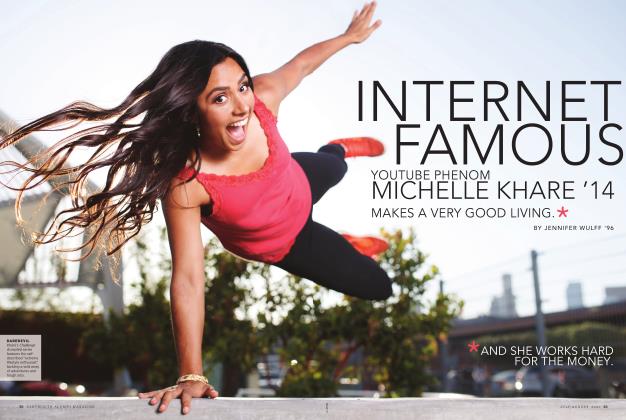

Cover StoryInternet Famous

JULY | AUGUST 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureFuturescapes

May 1974 By R.B.G.