THE PAPERS OF ADLAI STEVENSONEdited by Walter T. Johnson '37Little, Brown, 1979. Vol. VIII, 885 pp. $25

Adlai Stevenson's term as United States Ambassador to the United Nations was one long frustration, although the job like every job he handled was well and often brilliantly done. Who can forget the televised session of the Security Council at the time of the Cuban missile crisis, when Stevenson confronted the Soviet ambassador with the biting words, "I do not have your talent for obfuscation, for distortion, for confusing language and for doubletalk." Equally pungent and as memorable, had we but known it at the time, was his reaction to the Tonkin Gulf resolution, which it became his duty to defend although he had no previous knowledge of the circumstances out of which it arose. Of a State Department official he asked caustically, "What the hell were our ships doing there in the first place?" The latter incident occurred after the White House had changed tenant, but little else had changed.

Stevenson's towering prestige and global reputation for integrity were used by President Kennedy to shroud the Bay of Pigs. If Adlai Stevenson said there was no United States involvement, who would question it? But, of course, he had to be kept in the dark himself to give his words the ring of sincerity. Again and again, though perhaps not quite so flagrantly, the story was the same. Although his position made him the interpreter of his country to the rest of the civilized world, his views carried little actual weight with the policy-makers. Too often when measures that ran counter to his known convictions were to be implemented, he was only selectively informed, so that his widely respected conscience would not restrict his actions. He was persuaded, for example, to accept a small military operation in Santo Domingo to rescue American citizens, but soon found himself having to justify massive intervention.

In other cases information did not necessarily include support. For his role in bringing about a peaceful resolution of the Cuban missile crisis he was charged anonymously by the President himself with having sought a "Munich." The Vietnamese war was still new when Stevenson, working through United Nations Secretary-General U Thant, arranged for the two Vietnams and other interested nations to send delegates to some neutral ground for talks that might have ended the war in 1964, but the plan was brushed aside, first by President Johnson who feared it might interfere with the election, later by Defense Secretary McNamara, lest word of such talks upset the shaky Saigon government!

The labor of Stevenson's office was staggering, but he managed somehow to keep on top of the load, even to enjoy a few lighter moments and to find time for reflection. There was one occasion in May 1962, for example, when he wrote to a friend that he had returned from a fund-raising gala at three in the morning, "after several perilous encounters with Marilyn Monroe, dressed in... skin and beads. I didn't see the beads!" Barry Goldwater's presidential bid he shrugged off with a well-turned sentence: "I am still convinced that there is more sense in the goodness than in the fear and ignorance around us.

Adlai Stevenson was overworked, boneweary, frustrated, and considering retirement from public life when he suffered a fatal heart attack on a London street, July 13, 1965. This volume completes an impressive indeed an indispensible record of an outstanding career. To read this superbly edited and beautifully presented series helps us to understand a little better not only Adlai Stevenson and his time but ourselves as well.

Charles Wiltse, history professor emeritus, ischief editor of the Daniel Webster papers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Charles M. Wiltse

-

Books

BooksJOSHUA R. GIDDINGS AND THE TACTICS OF RADICAL POLITICS.

OCTOBER 1970 By Charles M. Wiltse -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF ADLAI STEVENSON.

January 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Article

ArticleWebster and a Small College

April 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF ADLAI E. STEVENSON. VOL. 4. LETS TALK SENSE TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE." 1952-1955

July 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksA Strong and Hungry Spirit

June 1975 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Books

BooksThe President's Secret

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Charles M. Wiltse

Books

-

Books

BooksACTING PROFESSIONALLY: RAW FACTS ABOUT ACTING AND THE ACTING BUSINESS.

NOVEMBER 1972 By ERIC FORSYTHE '69 -

Books

BooksTHE FEAR OF GOD.

November 1959 By FRANCIS W. GRAMLICH -

Books

BooksMINK AND RED HERRING,

October 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksWOODGATHERING: NOVEMBER SOVIET BOMB TESTS

NOVEMBER 1966 By JOHN PARKE '39 -

Books

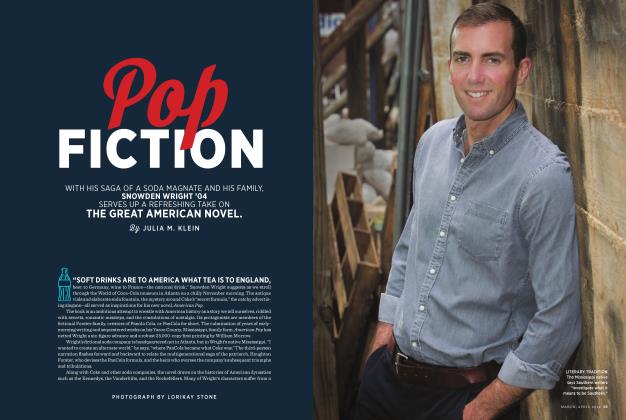

BooksPop Fiction

MARCH|APRIL 2019 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Books

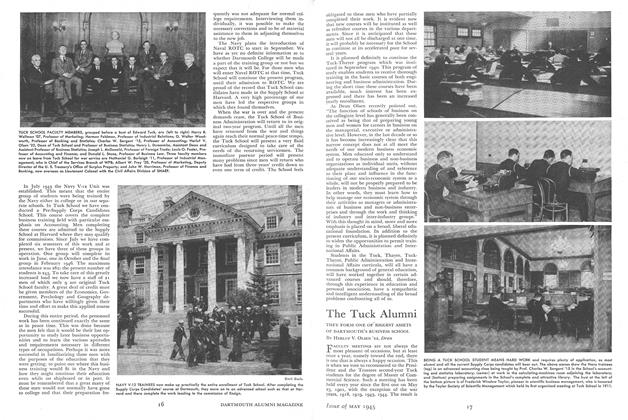

BooksNEW WORLD OF MACHINES

May 1945 By Virgil Poling