By David SViscott ’59. New York: W. W. Norton.Inc., 1970. 255 pp. $5.95.

This novel is a search for a young doctor’s own identity and sanity in a bizarre environment, a Cambridge (Mass.) mental hospital. As an interne, he wanted to establish order, to care about his patients, and to persuade them to care for him, but he was continually thwarted. Pipes leaked into cafeteria food and on to patients’ beds at night. He grew furious at husbands and wives for their cold-hearted indifference, at children and parents for abandoning one another, at society for malforming children and at teachers who beat them, at nurses for being naive and at aides for being cruel, at doctors for their stupidity and poor judgment, and at patients for resisting his efforts and playing tricks on him. How could he be sweet-tempered when he was spit upon, punched, kicked in the groin, showered with urine, and spattered with excrement? Persistent and humble, he did occasionally reach the unreachables. The last sentence is the key: “In helping people discover themselves, 1 had discovered more of me, and in the bargain, I became more human.”

Incidents from Dr. Robert Stevens’ past, shown in flashbacks, suggest that without luck, care, and love he too might have ended up unbalanced, if not insane. Exam- ples: when the large hospital lawns are covered with dandelions, a patient spends day after day picking them and wrapping them into bundles to distribute, unwanted, throughout the wards. Unfeelingly, a nurse throws them out. Dr. Stevens recalls that as a boy he compulsively picked dandelions for his mother. First delighted, she lost interest, and he was crushed. A patient when he touched a stone given power by Gabriel and speaks his own name backwards would be released from this hell to return to the paradise of home. The young doctor recalls his religious training: the little black boxes. phylacteries worn by his grandfather as a boy. Losing faith, the grandfather was religious only at Passover when he read the Hebrew text so rapidly that Robert Stevens and his sister would turn red holding back their laughter. The grandfather’s mind gave way, and committed, he died in the same asylum.

And so Dr. Robert Stevens moves experimentally through a mental hospital with such sympathy and frustration, with such enormous failures and such limited successes that he wonders what is real and what is illusion. What is real is himself newly discovered and his wife in the present with her love and support, and his family’s in the past. They, stable, and the insane, unstable, enable him to achieve balance and belief in himself as a physician able, at least in the outside world, to communicate.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

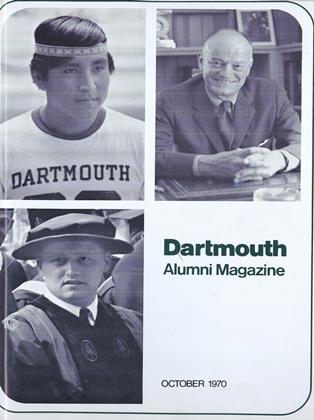

Cover Story

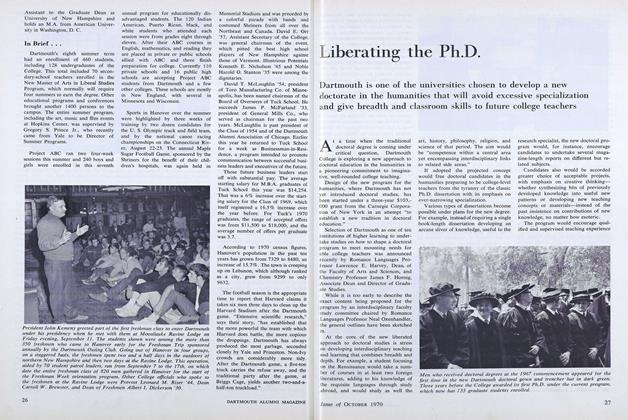

Cover StoryLiberating the Ph.D.

October 1970 By Robert B. Graham ’40 -

Feature

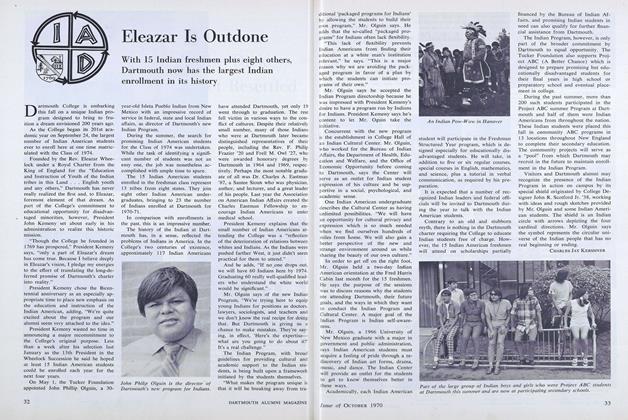

FeatureEleazar Is Outdone

October 1970 By Charles Jay Kershner -

Feature

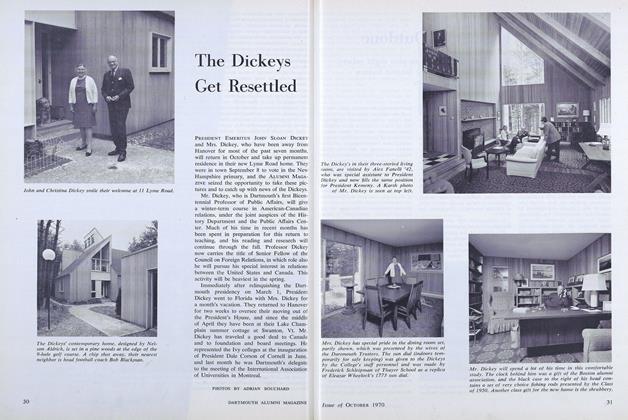

FeatureThe Dickeys Get Resettled

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleDear Mr. Cunningham . . .

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1970 By William R. Meyer -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

October 1970 By Jack DeGange

John Hurd ’21

Books

-

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

JULY 1970 -

Books

BooksPROFESSORS' BOOK SHELF

Mar/Apr 2008 -

Books

BooksThe Nuclear Dilemma

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By BERNARD D. NOSSITER '47 -

Books

BooksSpiritus Loci

February, 1931 By Eric P. Kelly -

Books

BooksPRINCIPLES OF ASTRONOMY.

JANUARY 1965 By GEORGE Z. DIMITROFF -

Books

BooksTHE RESTLESS HEART: BREAKING THE CYCLE OF SOCIAL IDENTITY.

March 1974 By H. GAYLORD HITCHCOCK'66