By Carlos Baker '32. Princeton UniversityPress. 1952. 322 pp. $4.50.

In view of Hemingway's achievement and the years that it has been recognized, it is surprising that there has been little good criticism of his work. Many critics have been confused by their strong feelings about Hemingway the man. Or they have been offended by the ideas expressed by some of his characters and have rather naively supposed that these ideas represent Hemingway's own views; they have belabored the man when they should have been trying to understand his work. Thus we have seen so intelligent a critic as Alfred Kazin maintaining that Hemingway is really only Jake Barnes or Robert Jordan his fictional "familiarly damned, familiarly self-absorbed lost generation Byron playing a part.. .

Professor Baker's scholarly study should do much to correct the errors of the past, errors made, for the most part, by critics whose primary concern has been the moral meaning and significance of Hemingway's writing. For, despite his title, Professor Baker seems to have been really more interested in this aspect, too. Working with a scholar's preference for fact over conjecture, he has gone back beyond legend and rumor to Hemingway's letters and the memoirs of his associates to discover Hemingway's true relation with the supposedly "lost" generation and to show that Hemingway was not lost, that he was not and never has been a nihilist. He shows how foolish it is to suppose that Brett Ashley, for example, speaks for Hemingway; and, having shown this, he can get on with the critic's proper business of understanding and evaluating what Hemingway really says, not in the parts but in the whole bodies of his works. What is said may represent a somewhat crude naturalism on Hemingway's part, but it is neither a Byronic pose nor sentimental negativism, and it provides Hemingway with a basis for significant, if somewhat limited, interpretations of human experience. For establishing beyond doubt Hemingway's moral fervor and ultimate optimism, Professor Baker deserves our gratitude.

His efforts to deal with Hemingway as artist are less rewarding, perhaps because he does not seem either very happy or very sure of himself when he tries to account for the esthetic interest of the work by analysis. He speaks rather hastily of something he terms the "emotionated substructure" of the great works, and, in another instance, he tries to account for Hemingway's craftsmanship in a passage on the slaying o£ a bull by counting the verbs in a sentence. Of the conclusion of this sentence he writes, "The massing, in that section of the sentence, of a half-dozen s's, compounded with tliejh sounds of swath and smoothly, can hardly have been inadvertent. They ease (or grease) the path of the bull's departure." But he is more persuasive when he relies upon impressionistic paraphrases of those passages which have given him delight, though this method is just a little suggestive of a guide's calling our attention to the celebrated local beauties. The paraphrases and certain comments on the works suggest that Professor Baker may regard language and form as quite independent containers which should be as unobtrusive as possible so that the intrinsic beauty of the subject may shine through. "It is," Professor Baker writes, "in great part his refusal to puddingize his plums that gives Hemingway's work its special quality of direct, undraped trans- scription from the life around him." If Professor Baker does indeed hold these views, they may explain his latent hostility to

" 'Pure,' or theoretical esthetics," which is so often concerned with just those aspects of literature that cannot be exhibited in a paraphrase. Speaking admiringly otf Hemingway's own contempt for such esthetics (a contempt which Hemingway may exaggerate), he writes, "One might even doubt that theoretical esthetics is of real interest to any genuine artist, unless in his alter ego he happens also to be a philosophical critic." But quite a number of genuine artists, Milton, Bach, Beethoven, Wordsworth, Wagner, James, Mann, Joyce, and Schonberg among them, have taken a lively interest in these matters; though, even if they had not, the work of some of our best contemporary critics demonstrates that this interest, if managed with wit and taste, can be of great assistance in defining the merit of such an extraordinary artist as Hemingway.

But i£ this study o£ "the writer as artist" leaves room for the insights of other critics, certainly it will help to make them more deeply penetrating and more valid by clearing away many of the obstacles which have obstructed the vision of critics and readers in the past. Incomplete, as any criticism must inevitably be, it is extremely useful. It belongs in the library of all admirers of Hemingway's work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOn Educational Policy

November 1952 By PROF. ANTON A. RAVEN -

Article

ArticleThe Business of Being a Gentleman

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

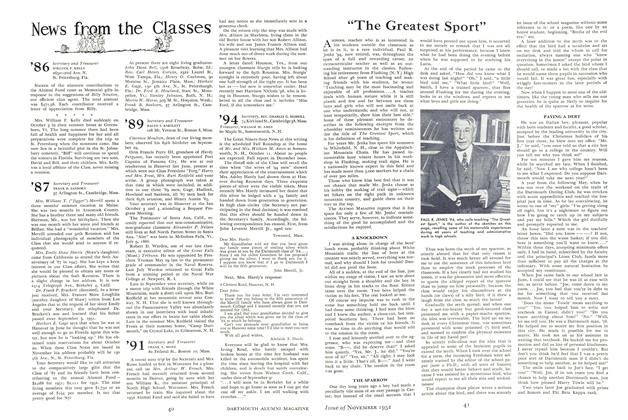

Article"The Greatest Sport"

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD

JOHN L. STEWART

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE OUTWARD VIEW.

OCTOBER 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksFILM IN THE THIRD REICH.

JANUARY 1970 By J. BLAIR WATSON JR. '21h -

Books

BooksBOTANY

July 1952 By James P. Poole -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN, INCLUDING PUERTO RICO AND THE VIRGIN ISLANDS.

NOVEMBER 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE EUROPEAN ANCESTRY OF VILLON'S SATIRICAL TESTAMENTS

February 1942 By Leon Verriest -

Books

BooksHISTORY OF GRANVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS.

March 1955 By NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH