Bob Blackman spent the final three weeks of the 1970 football season dodging the question, "How good is this Dartmouth team?"

He was reluctant to offer an answer because his mind could too quickly recall the events of November 22, 1969, a day when Dartmouth played at Princeton with mediocre results.

On the eve of the finale at Penn, it seems unrealistic to ask the same question, Rather, the query should be, "How great is the 1970 Dartmouth team?"

In 1969, the Indians seemed to reach a peak in the third week of the season as they obliterated Penn, 41-0. Certainly, they played well and won five more games before bowing at Princeton. But there never was that rare feeling that things were building toward a late-November crescendo.

Not so this fall. Even in whumping Yale in "the most lopsided 10-0 game in the history of college football" (as one veteran reporter described it), Dartmouth collected 480 yards to Yale's 190 in a display of versatile offense collaborating with a totally stingy defense that was convincing to everyone but the members of Black-man's squad.

"Maybe people will now think we're worth considering in the Lambert Trophy ratings," said defensive tackle Barry Brink, the 240-pound senior who is a legitimate Ail-American consideration and will play in the East-West Shrine game at Oakland, Calif., on January 2.

The people who vote took Brink's words to heart and Dartmouth immediately became a unanimous pick in the weekly Lambert balloting.

But while Brink was voicing what had to be an inevitability after the Yale win, halfback John Short was on the other side of the dressing room with other thoughts on his mind. "We played well," he said, "but I still don't think we've played our best game."

Short, the senior from Glendale, Ariz., who isn't exceptionally fast or big—or much more, really, than a solid fundamentalist who does everything right on a football field—is probably an even harder man to satisfy than Blackman himself.

"You couldn't ask more of a football player in one game than Shorty gave us at Harvard," said Blackman after Dartmouth's 37-14 victory.

What Short did to Harvard was the next thing to awesome: he carried the ball 25 times for 106 yards and scored two touchdowns. He caught six passes for 52 yards, one of them for another touchdown. He threw one pass on an option maneuver after taking a lateral pass from quarterback Jim Chasey. Short's toss was good for more than 25 of the 49 yards that split end Bob Brown traveled in producing another score.

Then, when the Ivy League's best punter, Jay Bennett, suffered a slight ankle sprain, Short was called on to punt. He had only one opportunity— and kicked the ball 35 yards where it died on the Harvard four-yard line.

What more could you ask? Said Short, "I didn't really play that well. I kicked myself in the calf in the first period and ran most of the game flatfooted. I could have been much better."

He had to be reasonably satisfied after Dartmouth's 24-0 win at Cornell. While the Indians were throttling the nation's leading runner, Cornell halfback Ed Marinaro (who averaged 166 yards per game at the kickoff and came away from the affair at Ithaca with a scanty 60 yards, his lowest output of the season), Short was strictly something else.

He was the driving force on a day when the Indians were frustrated for the better part of three periods by miscues, penalties, and an inspired Cornell defense. When he departed late in the fourth period, after Dartmouth had finally unloaded for three rapid-fire touchdowns, Short had amassed 192 yards in 28 carries. He caught one pass and also unleashed another completion to Ghasey on a quarterback-halfback-quarterback exchange that covered 21 yards.

Short's day at Cornell brought him within easy range of Dartmouth's single season rushing record. If he was satisfied, he didn't say so. "Great blocking," he said. "Brendan O'Neill, Stu Simms, Joe Leslie, and Darrel Gavle were really something."

And so it goes. On the eve of the Penn affair, the only thing that may satisfy this Dartmouth team is a touchdown every time they handle the ball and zero yardage for Penn. That would be something bordering on perfection—and that's the only thing that this team will settle for.

It's a team that must be considered extraordinary in the annals of Dartmouth football. The only problem is that, in their own minds, they may never really put together what they consider to be their best game.

Before the season began, Blackman was convinced that the Ivy League had a better overall balance of strength than in any other year. By the seventh week of the season, Dartmouth was averaging over 100 yards more on total offense than the closest Ivy rival. Defensively, the Indians were thoroughly unyielding. They zeroed Yale for the first time in the Elis' 32 games that preceded the affair in the Bowl. They did the same to Columbia and Cornell (making it five shutouts on the eve of Penn).

But they weren't really satisfied with any of it. Against Columbia, they were flatter than any other day of the season—and still had a 21-0 lead at the half. "We had a little 'discussion' at halftime," said Blackman, "and in the second half the team played with the pride and precision it has been noted for."

Precision is a good word for it. The Indians came out of the dressing room and methodically racked up 27 points in the next 16 minutes. Short scored twice before Bob Brown was given a chance to deliver another touchdown on "Alumni Play Number One"—an end-around production that was being saved for Bob's friends from New York (he comes from Massapequa). It was a 39-yard dash around left end and you could have nothing but pity for the lone Columbia defender who could do little but watch Brown approaching behind seven (count 'em) green-shirted blockers.

The coup de grace came moments later in the person of Tim Copper, the creative safety who has spent the entire season ranked among the nation's leading punt return specialists, "tie's got the corner," chortled Jake Crouthamel from the coaches' spotting booth in the Memorial Field press box, as Copper turned upfield and zigged past the remaining Columbia defenders.

While Chasey, the superbly efficient quarterback, has been demoralizing the opposition with persistent offensive marches, the attack has had the great advantage of working with excellent field position. That's because the defense has been equally outstanding. In an era of college football when points are going on the scoreboard with greater frequency than ever before, Dartmouth's defense has been building a reputation as a thoroughly unobliging adversary for all who try to cross the final stripe.

Dartmouth's defensive coaching staff—Crouthamel, Gary Golden, and Walt Anderson—are intense men. They've made defense a conversation piece in Dartmouth football. There is natural admiration for Chasey, Short, and the offensive unit that has been averaging better than 35 points a game. But now, too, they're equally excited by the exploits of Brink, Murry Bowden, Willie Bogan, and the rest of the defensive corps.

"Fans hear that whack when Bowden hits somebody and they love it," said Crouthamel. "Or, they watch Bogan match strides with a receiver, then bat the ball away. They appreciate the play."

Assuming the defense at Penn can stick to its best-in-nation average of 5.3 points allowed per game, the Indians should end up allowing less points in a nine-game season than any Dartmouth team since 1937. It's things like this that add an oft-forgotten dimension to the prowess of this Green horde.

At Harvard, when they presented Blackman with his 100 th win as Dartmouth's head coach, the Crimson managed only two first downs until the fourth period (when the Indians already had a 31-0 lead).

"Field position is so important and Dartmouth's defense gave their offense outstanding opportunities," said Harvard coach John Yovicsin. "This is a great Dartmouth team. They strangle you on defense and won't let you breathe on offense."

The unrelenting offense is triggered by Chasey, who rounded into sharp form at Harvard and clearly ranks as the best quarterback in the East this season. Against Harvard, he completed 15 of 26 passes for 145 yards. Most of the completions were on short, sideline cuts to Brown, Short, and O'Neill that were thoroughly frustrating to the Harvard defense.

At one point, he called the same play five successive times—and it worked every time. "I asked him if he shouldn't try something else," said Blackman of a conversation with Chasey during a time out. "His reply was, 'Why? They haven't stopped it yet."

At Yale, in a game that was long billed as the showdown for the Ivy title, the Elis never had a chance. Even though he played with a head cold and was thwarted by four Yale interceptions (including two in the Eli end zone), Chasey kept the Indians on a perpetual march up and down the Yale Bowl turf in a classic demonstration of field leadership.

All told, he completed 18 of 29 passes for 237 yards and while the Indians had to settle for O'Neill's three-yard touchdown run and a 30-yard field goal by Wayne Pirmann, the Indians were so convincing that Yale coach Carmen Cozza added his accolade to Yovicsin's.

Chasey's classiest day was against Columbia, though, as he carried the ball twice—and scored touchdowns on runs of one and 75 yards—and completed 11 of 17 passes for 151 yards. He didn't throw a scoring pass against the Lions but did the next best thing—a 53-yarder to sophomore split end Tyrone Byrd (one of the exciting players of the next two seasons) that went to the Lion three.

And the crowning touch for the latest in a line of outstanding Dartmouth quarterbacks: "I wouldn't trade him for anyone else in the country," said Blackman.

This is a team of intangibles—a group that has combined pride and confidence without cockiness, a group that has operated with cool, precise efficiency.

Perhaps these are the ingredients of greatness. For indeed, they have performed with the assuredness that comes from a blend of experienced seniors- Chasey, Short, Brown, Bowden, Brink, Bogan, and the perpetually unsung heroes of the inner world of the offensive line (Mark Stevenson at center, guards Bob Cordy and pint-sized Jim Wallace, plus the durable cocaptain at tackle, Bob Peters). Add the pillars of defense that have teamed with Bowden and Brink—Bill Skibitsky, Tim Risley, Bill Munich, Joe Jarrett, Russ Adams.

Take these people with a couple of outstanding juniors—Stu Simms, the block-busting fullback, and middle linebacker Wayne Young. Then inject the only sophomore starter, defensive end Fred Radke (who promises to be one of the outstanding players in the East in '71-72) and an amazing amount of predominantly sophomore depth that has had the opportunity to perform frequently, enthusiastically and effectively.

All the pieces have fallen together and been welded with typical Blackman magic.

It is a team of 26 seniors—sophisticated men who have come back from a day of frustration a year ago to clearly establish themselves as the leading characters on a one-way trip to success.

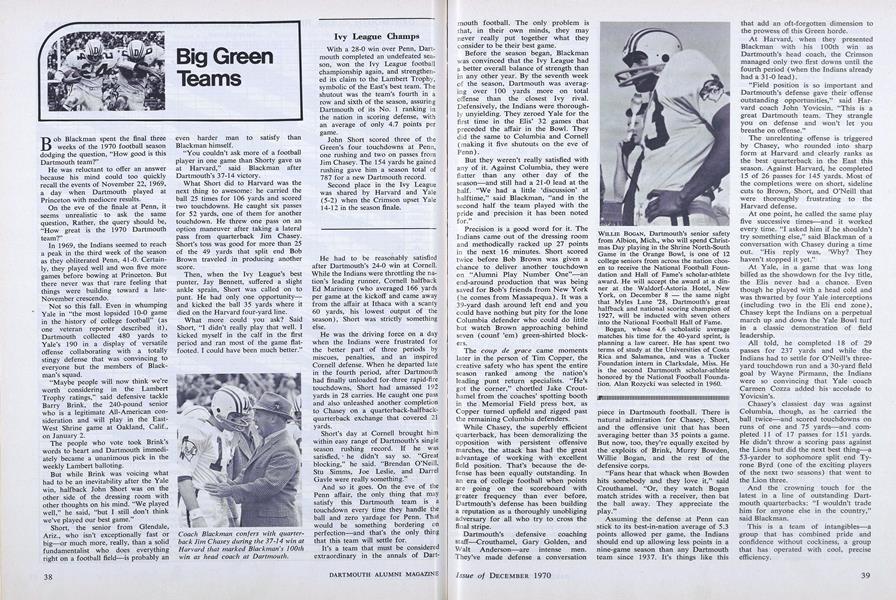

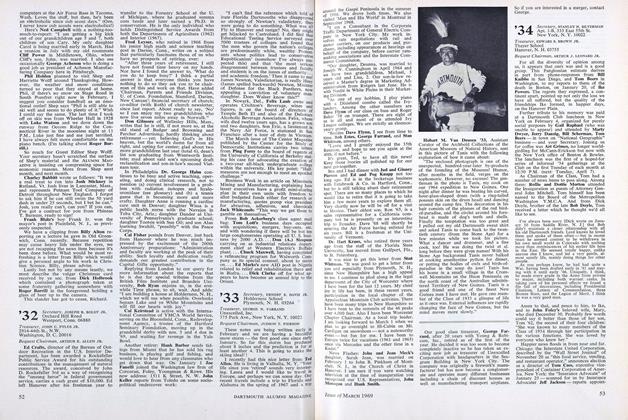

Coach Blackman confers with quarterback Jim Chasey during the 37-14 win atHarvard that marked Blackman's 100thwin as head coach at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe New Youth Culture

December 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe Outward Bound Term

December 1970 By Robert B. Graham Jr. '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

December 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1970 By CHRISTOPHER CROSBY '71 -

Article

ArticleRamon Guthrie's New Poem

December 1970 By James M. Reid '24

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW CURRICULUM IS ADOPTED; A. B. ONLY DEGREE TO BE GIVEN

June 1925 -

Article

ArticleMarch Enrollment

March 1945 -

Article

ArticleHobart M. Van Deusen '33

MARCH 1969 -

Article

ArticleSquash

February 1951 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleNotebook

May/June 2004 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Article

ArticleThe 35-Year Address

July 1950 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14