Houseparties weekend has come and gone with the usual flood of recent graduates racing back to partake in the communion of undergraduate existence. Dave said, "It's the best time of your life," and I guess he should know. He's been gone for five months now, and, like most others, is looking for something to do. "Listen, out there's Life. Live it up here while you can!" Even if it is true, it doesn't sound right. When I came here I got the impression it was to learn something about life out there, but often it's hard to get excited over either prospect. Apathy and disinterest seem to be the sacraments of most Dartmouth undergraduates. Indecision and frustration are their byproducts. Any extended activity, like the strike last spring, seems doomed to inevitable failure.

I suppose I'll have idyllic memories this time next year. I'll remember the parties and the friends and will have forgotten the pains of extended adolescence. But now I can't help wondering what it is that saps so much of the energy from Dartmouth, knowing at once it is a reflection of the forces that have created the chaotic and destructive social situation that surrounds the College today.

Much of this attitude has to do with us, the undergraduates who really are responsible for what does or doesn't happen here. At the same time, we're the products of the larger society that has shaped, taught, and guided us to Hanover. We're the Pepsi Generation, the culmination of the successful sixties, the embodiment of a technocratic society that has deemed science the answer for the future.

Dartmouth undergraduates are a generation that has grown up in a world of comparative affluence. More and faster cars, better homes and gardens, better health, communication and transportation systems that squeeze the world tighter within the hands of technological improvement all contribute to the ethic of manufactured existence we have known.

We have grown up under the moral assumption that science is the ultimate agent of mankind, the application of which will inevitably realize a Utopian state of existence ensuring wealth and health for the entire human race. Yet science has produced little in the way of ultimate answers. Inherent in technology is an objective, often skeptical attitude that manufactures an existence based solely on the criterion of utility, devoid of a higher integration of values that has been embodied in the religious and moral traditions of the past. We've been left in a moral vacuum, provided with no context for values other than the social criterion of extended ease of living.

We're the generation that began every Saturday morning with cartoons and soon graduated to Vietnam, to pollution, to a forced feeding of moral dilemmas in our living rooms from a society that provides no context for decision other than one of planned production.

Granted these are the facile and standard rationalizations for student unrest and the activization of youth. Yet in a world where the greater amount of education comes from television, we've known little but planned obsolescence. Confronted with a world where industrialized ease seems to promise no more than the choking of natural resources, impoverishment of the human soul and values, and the possible destruction of mankind by blind progressive technology, this same obsolescence has been extended and generalized to the preceding generation who unwittingly stand responsible for the failures as perceived in the present. "Never trust anyone over thirty" seems to be an unkind but common adage attributing the same poverty of moral perspective or control to the parents and leaders of the world today.

The unrest of students and the resulting activity, whether in dissent over American foreign policy or in actions designed to alleviate racial or environmental tension, is a direct result of the impoverished state of society today. It is an attempt to transcend the definitions of value posited in our culture in search of a greater source of meaning which hopefully will provide a context for more humane and rational action. In short, it is a desperate search for an overriding belief that will release the energies of the world's potentially most resourceful generation.

The strike last spring is an example of such an activity. Suddenly and irrevocably struck with the immense problems of our society through what was believed to be the real threat of President Nixon's action in Cambodia, students were forced into facing the moral crises of our time. The constructive activities that ensued represented the energies of one segment of our population in search of faith and a belief that could provide perspective for alleviating these immense problems.

The result of that activity was, for the majority, a reaffirmation of a growing skepticism. Much of the faith momentarily posited in the machinery of our governing system was shattered by an inability to effect any substantial movement toward change. Many students lobbying in Washington experienced outright hostility. The administration, moreover, seemed to foster the growth of a polarization between the youthful movements for change and a more conservative "silent majority."

There were constructive effects from the strike, however. For the first time many students experienced education as an exciting, open, and concretely valuable process, totally relevant to their lives and to their position in society. Dartmouth approximated the ideal of providing knowledge, not as four years of study divisible into 36 course units, but as a continuing process of integration providing methodologies for con- structing a context of values for making decisions throughout life. The College came close to the professed liberal arts ideal of educating the whole man, not only in terms of competence or conversance, but in conscience and commitment.

Yet now, after the initial enthusiasm has died and what faith developed has been broken, Dartmouth undergraduates have returned to an apathetic state of existence. Student participation in the electoral process was barely minimal. No voice was heard in protest when students were indicted in the Kent State incident. Active concern for racism and ecology has dissipated. The open, concerned, and active climate of Dartmouth has digressed to the familiar form of weekend activities inconveniently joined by weekdays and the responsibilities of academic life.

It is too harsh to make it sound as if students or Dartmouth are entirely to blame for the situation at present. The coercive nature of our society which holds the majority of students literally imprisoned at the College is hardly conducive to an intellectual or active campus. "Dartmouth, love it or leave it" is an easy thing to say from a removed and relatively secure position. Yet when one's life is actually threatened by the draft, coupled with the near impossibility of finding constructive employment, the relative ease of Dartmouth becomes a comfortable way of staving off the inevitable.

Dartmouth, as an institution, has done much more than other colleges to add an active component of social action to its curriculum. The Tucker Foundation and related programs offer students the opportunity of involving themselves in the social problems of our time.

However, none of this is adequate to absolve either party of responsibility for the apathetic climate at Dartmouth. What is needed is a radical reevaluation of the College's role in preparing men for participation in our society. Just as we are affected by the crises, values, and pressures of our culture, so is Dartmouth able to produce men who will actively effect the necessary changes in the basic social fabric. The tradition of preparing pre-professionals has been rejected by a large number of undergraduates and new alternatives are demanded. President Kemeny's idea of providing the world with skilled problem-solvers sounds only like the preparation of societal physicians. Knowledge and resulting educational systems have expanded drastically. Preparation on the undergraduate level in terms of the specialization and skill demanded by the crises we face is impossible and hardly a goal worth reaching for. Dartmouth must concern herself first with educating people. The strike served as eloquent illustration of a necessity for an education that is more concerned with providing a personally valuable and creative experience than one designed to ensure social success. Dartmouth must become actively involved in educating humane men, not doctors or lawyers. Their specialization on a graduate level will give them the skills necessary to effect change. What we must give them in a context of values for applying their energies.

Knowledge should not be presented as distinct disciplines embodying different problems, but as an integrated whole, each providing a different methodology and perspective for the study of a common problem, man and his relation to the world and to other men. We must effect a humane change on our own campus. An education must be provided that affords an immediate value to the experience of four years in Hanover, not one that can be cashed in on in the future. Dartmouth must continue its extension into the world, but we must also allow the world to enter the College.

Apathy breeds inactivity. The questions and crises that demand knowledge and action are not missing. What is missing is an educational experience that provides an immediate value for our existence in Hanover. Dartmouth and the world must become more humane places.

The Dartmouth Players opened their 1970-71 season with last month's productionof "him" by e. e. cummings. The play will be Dartmouth's entry in the 1971American College Theatre Festival, in which The Players had first-place successlast spring with Strindberg's "The Ghost Sonata."

Christopher Crosby '71, whose home isin Cazenovia, N. Y., is an honors majorin religion and the student representativefrom the humanities on the Committeeon Educational Policy. Among his manycampus activities, he is managing editorof the Dartmouth Course Guide, a headinstructor in rec skiing, informationcoordinator for Project ABC, and amember of Alpha Theta fraternity. Hewas a member of last May's Strike Committee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

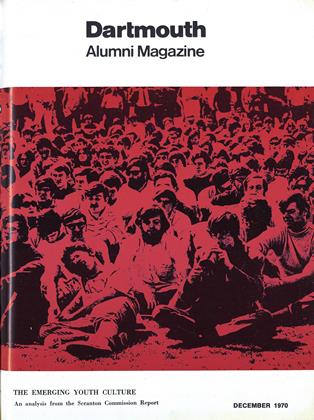

FeatureThe New Youth Culture

December 1970 -

Feature

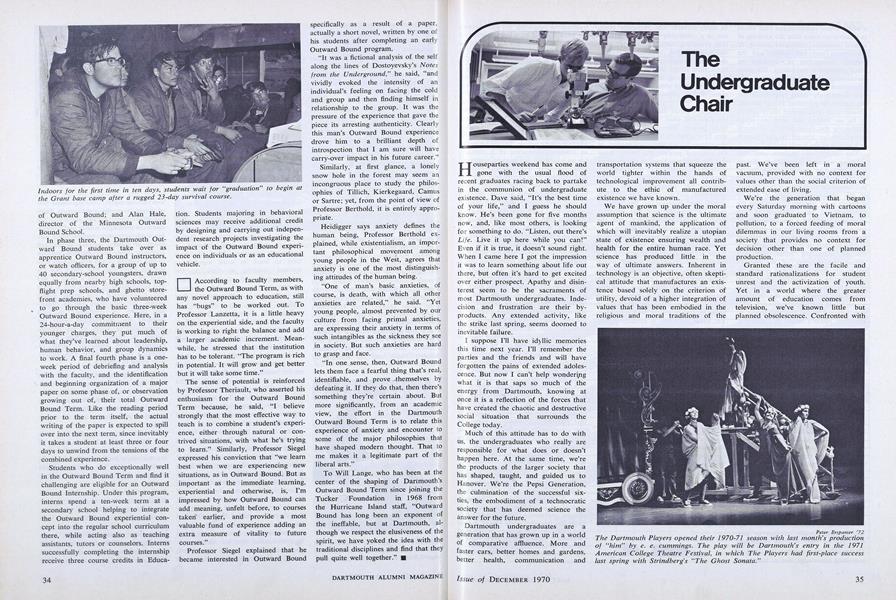

FeatureThe Outward Bound Term

December 1970 By Robert B. Graham Jr. '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

December 1970 -

Article

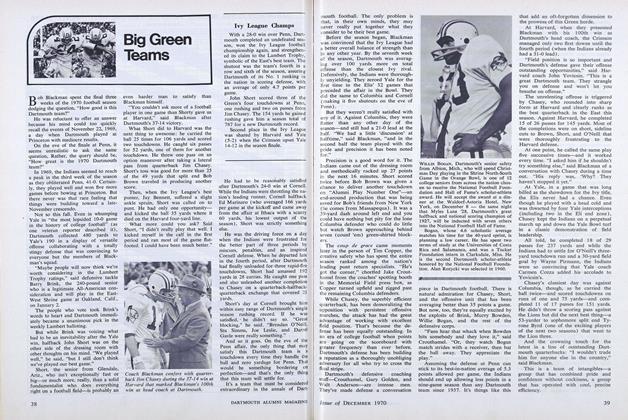

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleRamon Guthrie's New Poem

December 1970 By James M. Reid '24