"In and of itself, campus unrest is not a 'problem' and requires no 'solution.' The existence of dissenting opinion and voices is simply a social condition, a fact of modern life..."

Our purpose in this chapter is to identify the causes of student protest and to ascertain what these causes reveal about its nature. Our subject is primarily the protest of white students, for although they have much in common with black, Chicano, and other minority student protest movements, these latter are nevertheless fundamentally different in their goals, their intentions, and their sources. In Chapter 3 we consider the special case of the black student movement.

We find that campus unrest has many causes, that several of these are not within the control of individuals or of government, and that some of these causes have worked their influence in obscure or indirect ways. Identifying them all is difficult, but they do exist and must be sought — not in order to justify or condemn, but rather because no rational response to campus unrest is possible until its nature and causes have been fully understood.

Race, the war, and the defects of the modern university have contributed to the development of campus unrest, have given it specific focus, and continue to lend it a special intensity. But they are neither the only nor even the most important causes of campus unrest.

Of far greater moment have been the advance of American society into the post-industrial era, the increasing affluence of most Americans, and the expansion and intergenerational evolution of liberal idealism. Together, these have prompted the formation of a new youth culture that defines itself through a passionate attachment to principle and an opposition to the larger society. At the center of this culture is a romantic celebration of human life, of the unencumbered individual, of the senses, and of nature. It rejects what it sees to be the operational ideals of American society: materialism, competition, rationalism, technology, consumerism, and militarism. This emerging culture is the deeper cause of student protest against war, racial injustice and the abuses of the multiversity.

During the past decade, this youth culture developed rapidly. It has become ever more distinct and has acquired an almost religious fervor through a process of advancing personal commitment. This process has been spurred by the emergence of opposition to the youth culture and particularly to its demonstrations of political protest. As such opposition became manifest—and occasionally violently manifest—participants in the youth culture felt challenged, and their commitment to that culture, and to political protest, grew stronger and bolder. Over time, more and more students have moved in the direction of an ever deeper and more inclusive sense of opposition to the larger society. As their alienation became more profound, their willingness to use violence increased.

American student protest, like the student protest which is prevalent around the world, thus signifies a broad and intense reaction against — and a possible future change in — modern Western society and its organizing institutions. It thus appears to define a broad crisis of values with which the American people must now begin to cope.

Given that campus unrest reflects such broad causes and historical forces, it is perhaps not surprising that most Americans find student protest so puzzling. They believe that protest comes only from groups which suffer injustice and economic privation; yet white student protesters come predominantly from affluent families, attend the better and the larger universities, and have easy access to the highest rewards and positions that American society can offer. Most Americans believe that protest arises only when the conditions at issue are getting sharply worse; yet the trend of American society, as they see it, is one of progress, albeit sometimes slow, toward the reforms students seek — in personal income, in housing, in health, in equal opportunity, in civil liberties, and even in the national involvement with the war. And finally, most Americans believe that an authentic idealism expresses itself only in peaceful and humane ways; yet although students manifest a high idealism, some student protest reveals in its tactical behavior a contrary tendency toward intolerance, disruption, criminality, destruction, and violence.

Thus, many Americans consider campus unrest to be an aberration from the moral order of American society. They treat it as a problem that derives from some moral failing on the part of some individual or group. The explanations of campus unrest which they adopt therefore tend to be single-cause explanations that allocate blame and indicate remedies that are within the capacity of individuals, public opinion, or government to provide. Three such explanations enjoy particular popularity today.

One explanation attributes campus unrest to the machinations of outside agitators and subversive propagandists.

It is clear that in some cases of campus disruption, agitators and professional revolutionaries have been on the scene doing whatever they could do to make dangerous situations worse. It also is true that some of the most violent and destructive actions, such, perhaps, as the bombing in Madison, Wisconsin, this summer, are attributable to the influence, if not the actions, of small, trained, and highly mobile groups of revolutionaries. But it is equally clear that such agitators are not the cause of most large-scale campus protest and disorders. Agitators take advantage of preexisting tensions and seek to exacerbate them. But except for individual acts of terrorism, agitation and agitators cannot succeed if an atmosphere of tension, frustration, and dissent does not already pervade the campus. If agitation has contributed to campus unrest—and clearly, in various ways, it has—then it has done so only because such an atmosphere has existed. What, then, created this atmosphere? The "agitator" theory cannot answer this question.

A second popular school of explanation holds that the atmosphere of dissent and frustration on campuses is the result of the pressing and unresolved issues which deeply concern many students. Clearly such issues do exist and do arouse deep feeling. Yet the conditions to which the issues have reference are in most cases not new ones. Why, then, have these issues recently emerged as objects of student protest and as sources of campus tension? And why has that protest become increasingly disruptive and violent? The "issues" theory does not answer these questions.

The third popular school of explanation argues that campus unrest is caused by an increasing disrespect for law and by a general erosion of all stabilizing institutions—weakening of family, especially by "permissive" methods of child rearing, and of church, school, and patriotism. To some degree and in some areas, such an erosion of the stabilizing institutions in American society has taken place. Yet we must ask: Why has this erosion taken place? The "breakdown of law" theory does not have an answer.

The basic difficulty with these explanations is that they begin by assuming that all campus unrest is a problem—a problem whose cause is a moral failure on the part of students or of society or of government, and which therefore has a specific solution. The search for cause is thus inseparable from the assignment of blame and advocacy of some course of public action. As a result, causes which are not within human control or which do not lay the mantle of culpability upon specifiable individuals or groups tend to be ignored. Such "explanations" do not really explain. They only make "campus unrest" more bewildering—and more polarizing—than it need be.

For, in and of itself, campus unrest is not a "problem" and requires no "solution." The existence of dissenting opinion and voices is simply a social condition, a fact of modern life; the right of such opinion to exist is protected by our Constitution. Protest that is violent or disruptive is, of course, a very real problem, and solutions must be found to end such manifestations of it. But when student protest stays within legal bounds, as it typically does, it is not a problem for government to cope with. It is simply a pattern of opinion and expression.

Campus unrest, then, is not a single or uniform thing. Rather it is the aggregate result, or sum, of hundreds and thousands of individual beliefs and discontents, each of them as unique as the individuals who feel them. These individual feelings reflect in turn a series of choices each person makes about what he will believe, what he will say, and what he will do. In the most immediate and operational sense, then, it is these choices—these commitments, to use a word in common usage among students—which are the proximate cause of campus unrest, and which are the forces at work behind any physical manifestation of dissent or dissatisfaction.

These acts of individual commitment to certain values and to certain ways of seeing and acting in the world do not occur in a vacuum. They take place within, and are powerfully affected by, the conditions under which students live. We will call these conditions the contributing causes of campus unrest. Five broad orders of such contributing causes have been suggested in testimony before the Commission. They are:

► The pressing problems of American society, particularly the war in Southeast Asia and the conditions of minority groups;

► The changing status and attitudes of youth in America;

► The distinctive character of the American university during the postwar period;

► An escalating spiral of reaction to student protest from public opinion and an escalating spiral of violence; and

► Broad evolutionary changes occurring in the culture and structure of modern Western society.

Issues and Opinions

The best place to begin any search for the causes of student protest is to consider the reasons which student protesters themselves offer for their activities. There are many such reasons, and students are not reluctant to articulate them. These reasons—these positions on the major national issues of the day—must be taken seriously.

We must recognize, however, that students express a keen interest in a large number of issues. Even in the course of a single re-enactment of the Berkeley scenario, the issues which are identified and discussed, and which in some degree are the reasons for student participation, can number in the tens or scores.

For example, a protest against university expansion into the neighboring community and against university complicity in the Vietnam war may lead to university discipline. Discipline or amnesty may then become the issue. On this issue there is a larger and more disruptive protest. The police are called. Police brutality now becomes the issue, and the demand is that the university intercede to get students released. The university says this is a matter for the civil courts. It is now attacked as inhuman and soulless and dominated by the material interests of its trustees, who need police and courts to protect those interests. At this point a building goes up in flames. What was the issue?

One must distinguish therefore between primary issues and secondary issues, which arise from protest actions or from the primary issues themselves. Three great primary issues have been involved in the rising tide of student protest during the past decade.

Both historically and in terms of the relative frequency with which it is the focus of protest, the first great issue is also the central social and political problem of American society: the position of racial minorities, and of black people in particular. It was over this issue that student protest began in 1960.

As the decade passed, the definition of this issue changed. At first, it was defined in the South as the problem of legally enforced or protected patterns of segregation. Later, the focus shifted to the problems of extra-legal discrimination against blacks, in the North as well as in the South—a definition of the issues which later was summarized in the phrase "institutional racism." By the middle of the decade, the issue had shifted again, and now was understood as a problem of recovering the black's self-respect and pride in his cultural heritage.

The targets of protest have shifted accordingly. At first, there was protest against local merchants for not serving blacks, against local businesses for not employing them, and against the university for tolerating discrimination in sororities and fraternities. Soon there were protests against discrimination in university admissions and demands that more be done to recruit blacks and that more be done to assist them once admitted. Black students demanded too that the university begin to give assistance to local black communities, that it establish a curriculum in black studies, and that it recruit more black faculty to teach courses in these and other areas. As the target of protest moved from the society at large to the university, it also widened to represent the aspirations of other minority groups, often in a "Third World" coalition.

The second great issue has been the war in Southeast Asia. The war was almost from the beginning a relatively unpopular war, one which college youth on the whole now consider a mistake, and which many of them also consider immoral and evil. It has continued now for more than five years, and it has pressed especially on youth. During the last decade, the war issue was less commonly the object of student protest than were questions of race, but as the years went by it became more and more prominent among student concerns.

This issue has also changed form and has become more inclusive over the years: it moved from protesting American intervention, to protesting the draft, to protesting government and corporate recruiting for jobs related to the war, and increasingly to protesting university involvement in any aspect of the war, such as releasing information to draft boards, allowing recruiters on campus, conducting defense research, and permitting the presence of ROTC on campus.

A third major protest issue has been the university itself. Though at times this issue has been expressed in protests over curriculum and the non-retention of popular teachers, the overwhelming majority of university-related protests have dealt with school regulations affecting students, with the role of students in making those regulations, and more generally with the quality of student life, living facilities, and food services. The same impulse moves students to renounce what they feel to be the general regimentation of American life by largescale organizations and their by-products—impersonal bureaucracy and the anonymous IBM card. University regulation of political activities—the issue at Berkeley in 1964—has also been a prominent issue.

Since 1965 there has been steady liberalization in the rules affecting student living quarters, disciplining of students, rules affecting controversial speakers, and dress rules. Increasingly universities and colleges have incorporated students into the rulemaking process. Yet the issue has lost none of its power.

What students objected to about discrimination against blacks and other racial minorities was simple and basic: the unfeeling and unjustifiable deprivation of individual rights, dignity, and self-respect. And the targets of protest were those institutions which routinely deprived blacks of their rights, or which supported and reinforced such deprivation. These two themes—support for the autonomy, personal dignity, individuality, and life of the individual, and bitter opposition to institutions, policies, and rationales which seemed to deprive individuals of those things—could also be seen in the other two main issues of the 1960's: the war in Southeast Asia, and university regulation of student life. They may also be seen in the emerging student concern over ecology and environmental pollution.

These three issues—racism, war, and the denial of personal freedoms—unquestionably were and still are contributing causes of student protest. Students have reacted strongly to these issues, speak about them with eloquence and passion, and act on them with great energy.

Moreover, students feel that government, the university, and other American institutions have not responded to their analysis of what should be done, or at least not responded rapidly enough. This has led many students to turn their attacks on the decision-making process itself. Thus, we hear slogans like "power to the people."

And yet, having noted that these issues were causes, we must go on to note two further, pertinent facts about student protest over race and war. First, excepting black students, it is impossible to attribute student opposition on these issues to cynical or narrow self-interest alone, as do those Americans who believe that students who are against the war are cowards because they are afraid to die for any cause. In fact, few students are called upon to risk their lives in war. It is true that male students have been subject to the draft. But only a small proportion of college youth have actually been drafted and sent to fight in Vietnam, and it is reported that, as compared to the nation's previous wars, relatively few college graduates have been killed in this war. It is non-college youth who fight in Vietnam, and yet it is college youth who oppose the war — while non-college youth tend to support it more than other segments of the population.

It is the same in the case of race. For black and other minority college youth, it hardly needs explanation why they should find the cruel injustice of American racism a compelling issue, or why they should protest over it. Why it became an issue leading to unrest among white college students is less obvious. They are not directly victims of it, and as compared to other major institutions in the society the university tends to be more open and more willing to reward achievement regardless of race or ethnicity.

Of course, students have a deep personal interest in these issues and believe that the outcome will make their own individual lives better or worse. But their beliefs and their protest are clearly founded on principle and ideology, not on self-interest. The war and the race issues did not arise primarily because they actually and materially affected the day-to-day lives of college youth—black students again excepted. The issues were defined in terms not of interest but of principle, and their emergence was based on what we must infer to have been a fundamental change in the attitudes and principles of American students. . . .

If, then, war and racism did not directly and significantly affect the daily lives and self-interest of the vast majority of American students, if war and racism were not new to American society, and if their horrors and injustices were, over time, marginally diminishing rather than increasing—the emergence on campus of these issues as objects of increasingly widespread student protest could only have been the result of some further cause, a change in some factor that intervened between the conditions (racism, war) in the country, and their emergence as issues which led to student protest.

Clearly, whatever it is that transforms a condition into an issue lies in the eyes of the beholder—or more precisely, in his opinions and perceptions. The emergence of these issues was caused by a change in opinions, perceptions, and values—that is, by a change in the culture of students. Students' basic ways of seeing the world became, during the 1960'5, less and less tolerant of war, of racism, and of the things these entail. This shift in student culture is a basic—perhaps the basic—contributing cause of campus unrest.

The New Youth Culture

In early western societies, the young were traditionally submissive to adults. Largely because adults retained great authority, the only way for the young to achieve wealth, power, and prestige was through a cooperative apprenticeship of some sort to the adult world. Thus, the young learned the traditional adult ways of living, and in time, they grew up to become adults of the same sort as their parents, living in the same sort of world.

Advancing industrialism decisively changed this cooperative relationship between the generations. It produced new forms and new sources of wealth, power, and prestige, and these weakened traditional adult controls over the young. It removed production from the home, and made it increasingly specialized; as a result, the young were increasingly removed from adult work places and could not directly observe or participate in adult work. Moreover, industrialism hastened the separation of education from the home, and the young were increasingly concentrated together in places of formal education that were isolated from most adults. Thus, the young spent an increasing amount of time together, apart from their parents' home and work, in activities that were different from those of adults.

This shared and distinct experience among the young led to shared interests and problems, which led, in turn, to the development of distinct subcultures. As those subcultures developed, they provided support for any youth movement distinct from—or even directed against - the adult world.

A distinguishing characteristic of young people is their penchant for pure idealism. Society teaches youth to adhere to the basic values of the adult social system—equality, honesty, democracy, or whatever—in absolute terms. Throughout most of American history, the idealism of youth has been formed—and constrained—by the institutions of adult society. But during the 1960's, in response to an accumulation of social changes, the traditional American youth culture developed rapidly in the direction of an oppositional stance toward the institutions and ways of the adult world.

This subculture took its bearings from the notion of the autonomous, self-determining individual whose goal was to live with "authenticity," or in harmony with his inner penchants and instincts. It also found its identity in a rejection of the work ethic, materialism, and conventional social norms and pieties. Indeed, it rejected all institutional disciplines externally imposed upon the individual, and this set it at odds with much in American society.

Its aim was to liberate human consciousness and to enhance the quality of experience; it sought to replace the materialism, the self-denial, and the striving for achievement that characterized the existing society with a new emphasis on the expressive, the creative, the imaginative. The tools of the workaday institutional world—hierarchy, discipline, rules, self-interest, self-defense, power—it considered mad and tyrannical. It proclaimed instead the liberation of the individual to feel, to experience, to express whatever his unique humanity prompted. And its perceptions of the world grew ever more distant from the perceptions of the existing culture: what most called "justice" or "peace" or "accomplishment" the new culture envisioned as "enslavement" or "hysteria" or "meaninglessness." As this divergence of values and of vision proceeded, the new youth culture became increasingly oppositional.

And yet in its commitment to liberty and equality, it was very much in the mainstream of American tradition; what it doubted was that America had managed to live up to its national ideals. Over time, these doubts grew, and youth culture became increasingly imbued with a sense of alienation and of opposition to the larger society.

No one who lives in contemporary America can be unaware of the surface manifestations of this new youth culture. Dress is highly distinctive; emphasis is placed on heightened color and sound; the enjoyment of flowers and nature is given a high priority. The fullest ranges of sense and sensation are to be enjoyed each day through the cultivation of new experiences, through spiritualism, and through drugs. Life is sought to be made as simple, primitive, and "natural" as possible, as ritualized, for example, by nude bathing.

Social historians can find parallels to this culture in the past. One is reminded of Bacchic cults in ancient Greece, or of the wandering bands of German students in the early 19th century, the Wander-voegelen, or of primitive Christianity. Confidence is placed in revelation rather than cognition, in sensation rather than analysis, in the personal rather than the institutional. Emphasis is placed on living to the fullest extent, on the sacredness of life itself, and on the common mystery of all living things. The ancient vision of natural man, untrammeled and unscarred by the fetters of institutions, is seen again. It is not necessary to describe such movements as "religious," but it is useful to recognize that they have elements in common with the waves of religious fervor that periodically have captivated the minds of men.

It is not difficult to compose a picture of contemporary America as it looks through the eyes of one whose premises are essentially those just described. Human life is all; but women and children are being killed in Vietnam by American forces. All living things are sacred; but American industry and technology are polluting the air and the streams, and killing the birds and the fish. The individual should stand as an individual; but American society is organized into vast structures of unions, corporations, multiversities, and government bureaucracies. Personal regard for each human being and for the absolute equality of every human soul is a categorical imperative; but American society continues to be characterized by racial injustice and discrimination. The senses and the instincts are to be trusted first; but American technology, and its consequences, are a monument to rationalism. Life should be lived in communion with others, and each day's sunrise and sunset enjoyed to the fullest; American society extols competition, the accumulation of goods, and the work ethic. Each man should be free to lead his own life in his own way; American organizations and statute books are filled with regulations governing dress, sex, consumption, and the accreditation of study and of work, and many of these are enforced by armed police.

No coherent political decalogue has yet emerged. Yet in this new youth culture's political discussion there are echoes of Marxism, of peasant communalism, of Thoreau, of Rousseau, of the evangelical fervor of the abolitionists, of Gandhi, and of native American populism.

The new culture adherent believes he sees an America that has failed to achieve its social targets; that no longer cares about achieving them; that is thoroughly hypocritical in pretending to have achieved them and in pretending to care; and that is exporting death and oppression abroad through its military and corporate operations. He wishes desperately to recall America to its great traditional goals of true freedom and justice for every man. As he see it, he wants to remake America in its own image....

The dedicated practitioners of this emerging culture typically have little regard for the past experience of others. Indeed, they often exhibit a positive antagonism to the study of history. Believing that there is today, and will be tomorrow, a wholly new world, they see no special relevance in the past. Distrusting older generations, they distrust the motives of their historically based advice no less than they distrust the history written by older generations. The antirationalist thread in the new culture resists the careful empirical approach of history and denounces it as fraudulent. Indeed, this anti-rationalism, and the urge for blunt directness often leads those of the new culture to view complexity as a disguise, to be impatient with learning the facts, and to demand simplistic solutions in one sentence.

Understandably, the new culture enthusiast has, at best, a lukewarm interest in free speech, majority opinion, and the rest of the tenets of liberal democracy as they are institutionalized today. He cannot have much regard for these things if he believes that American liberal democracy, with the consent and approval of the vast majority of its citizens, is pursuing values and policies that he sees as fundamentally immoral and apocalyptically destructive. Again, in parallel with historical religious movements, the new culture advocate tends to be self-righ-teous, sanctimonious, contemptuous of those who have not yet shared the vision, and intolerant of their ideals.

Profoundly opposed to any kind of authority structure from within or without the movement and urgently pressing for direct personal participation by each individual, members of this new youth culture have a difficult time making collective decisions. They reveal a distinct intolerance in their refusal to listen to those outside the new culture and in their willingness to force others to their own views. They even show an elitist streak in their premise that the rest of the society must be brought to the policy positions which they believe are right.

At the same time, they try very hard, and with extraordinary patience, to give each of their fellows an opportunity to be heard and to participate directly in decision-making. The new culture decisional style is founded on the endless mass meeting at which there is no chairman and no agenda, and from which the crowd or parts of the crowd melt or move off into actions. Such crowds are, of course, subject to easy manipulation by skillful agitators and sometimes become mobs. But it must also be recognized that large, loose, floating crowds represent for participants in the new youth culture the normal, friendly, natural way for human beings to come together equally, to communicate, and to decide what to do. Seen from this perspective, the reader may well imagine the general student response at Kent State, to the Governor's order that the National Guard disperse all assemblies, peaceful or otherwise.

Practitioners of the new youth culture do not announce their program because the movement is not primarily concerned with programs; it is concerned with how one ought to live and what he ought to consider important in his daily life. The new culture is still in the process of forming its values, programs, and life style; at this point; therefore, it is primarily a stance.

A parallel to religious history is again instructive. For many (not all) student activists and protesters, it is not really very important whether the protest tactics employed will actually contribute to the political end allegedly sought. What is important is that a protest be made—that the individual protester, for his own internal salvation, stand up, declare the purity of his own heart, and take his stand. No student protester throwing a rock through a laboratory window believes that it will stop the Indochina war, weapons research, or the advance of the feared technology—but he throws it in a mood of defiant exultation—almost exaltation. He has taken his moral stance.

An important theme of this new culture is its oppositional relationship to the larger society, as is suggested by the fact that one of its leading theorists has called it a "counter culture." If the rest of the society wears short hair, the member of this youth culture wears his hair long. If others are clean, he is dirty. If others drink alcohol and illegalize marijuana, he denounces alcohol and smokes pot. If others work in large organizations with massively complex technology, he works alone and makes sandals by hand. If others live separated, he lives in a commune. If others are for the police and the judges, he is for the accused and the prisoner. By these means, he declares himself an alien in a large society with which he fundamentally is at odds.

He will also resist when the forces of the outside society seek to impose its tenets upon him. He is likely to see police as the repressive minions of the outside culture imposing its law on him and on other students by force or death, if necessary. He will likely try to urge others to join him in changing the society about him, in the conviction that he is seeking to save that society from bringing about its own destruction. He is likely to have apocalyptic visions of impending doom of the whole social structure and the world. He is likely to have lost hope that society can be brought to change through its own procedures. And if his psychological make-up is of a particular kind, he may conclude that the only outlet for his feelings is violence and terrorism.

In recent years, some substantial number of students, in the United States and abroad, have come to hold views along these lines. It is also true that a very large fraction of American college students, probably a majority, could not be said to be participants in any significant aspect of this cultural posture, except for its music. As for the rest of the students, they are distributed over the entire spectrum that ranges from no participation to full participation. A student may feel strongly about any one or more aspects of these views, and wholly reject all the others. He may also subscribe wholeheartedly to many of the philosophic assertions implied while occupying any of hundreds of different possible positions on the questions of which tactics, procedures, and actions he considers to be morally justifiable. Generalizations here are more than usually false.

One student may adopt the outward appearance of the new culture and nothing else. Another may be a total devotee, except that he is a serious history scholar. Another student may agree completely on all the issues of war, race, pollution, and the like, and participate in protests over those matters, while disagreeing with all aspects of the youth culture life style. A student may agree with the entire life style, but be wholly uninterested in politics. Another new culture student who takes very seriously the compassion and life aspects may prove to the the best bulwark against resorts to violence. A student who rejects the new youth culture altogether may, nevertheless, be in the vanguard of those who seek to protect that culture against the outside world. And so forth.

As is observed elsewhere in this report, to conclude that a student who has a beard is a student who would burn a building, or even sit-in in a building, is wholly unwarranted.

But almost no college student today is unaffected by the new youth culture in some way. ff he is not included, his roommate or sister or girl friend is. If protest breaks out on his campus, he is confronted with a personal decision about his role in it. In the poetry, music, movies, and plays that students see, the themes of the new culture are recurrent. Even the student who finds older values more comfortable for himself will, nevertheless, protect and support vigorously the privilege of other students who prefer the new youth culture.

A vast majority of students are not adherents. But no significant group of students would join older generations in condemning those who are. And almost all students will condemn repressive efforts by the larger community to restrict or limit the life style, the art forms, and the non-violent political manifestations of the new youth culture.

To most Americans, the development of the new youth culture is an unpleasant and often frightening phenomenon. And there is no doubt that the emergence of this student perspective had led to confrontations, injuries, and death. It is undeniable, too, that a tiny extreme fringe of fanatical devotees of the new culture have crossed the line over into outlawry and terrorism. There is a fearful and terrible irony here as, in the name of the law, police and National Guards have killed students, and some students under the new culture's banner of love anl compassion have turned to burning and bombing.

But the new youth culture itself is not a "problem" to which there is a "solution"; it is a mass social condition, a shift in basic cultural viewpoint. How long this emerging youth culture will last, and what course its future development will take, are open questions. But it does exist today, and it is the deeper cause of the emergence of the issues of race and war as objects of intense concern on the American campus.

The Changing University

This change in the youth subculture is related to major changes in the social functions and internal composition of the American university.

The American university was traditionally a status-conferring institution for middle and upper-middle class families. As such, it was closely integrated with the family and work life of these social groupings, and its subcultures were appropriately cooperative.

The college experience provided an identity moratorium following childhood. Students spent the "best years of their lives" mostly enjoying themselves with good conversation, some study, football, dating, and drinking. The experience ended with a "rite de passage, graduation, which was then followed by adulthood and entry into the "serious world of work." The college was completely controlled by the serious adult world, but the student's experiences there were not seen by him or others as part of that world.

In the past few decades, the university has become increasingly integrated into the meritocratic work world. Grade pressures have grown steadily, and students have come to see the university as a direct extension of the adult world. Indeed, by the 1960's, this trend had moved down into the high schools and in some places even to the junior high schools, as formal education became the primary route to the best jobs in the postindustrial society.

The integration of higher education into the adult world was intimately associated with another historic change —the rapid expansion of higher education, and the dramatic increase in the proportion of high school graduates who entered college. In the early 1930's there were about a million and a quarter college students in the United States. In the fall of 1969, there were over seven million. By 1978, we may look forward to ten million, and there will be almost as many graduate students enrolled as there were undergraduates before World War 11. The U. S. Office of Education now estimates that, nationally, 62 percent of all high school graduates will attend institutions of higher education.

As higher education expanded, it also lengthened. More and more students went on to enroll in graduate programs leading to advanced degrees; as they did, the vocational value of the undergraduate degree decreased. Students thus were under pressure to spend an even longer period of time—well into their 20's, and not infrequently into the early 30's—in schools which prepared them for the even longer deferred work world.

More and more young Americans found themselves in an ambivalent status for an ever longer time. Physically and psychologically, they had long since become adult. As students in the meritocratic system of higher education, they were already integrated into a part of the adult work world. Accordingly, they came to think of themselves as adults and to demand all the rights and privileges of adults. And yet, though in part they were treated as adults, they nevertheless remained financially dependent upon the adult world and were not yet full-fledged participants in adult work. Especially for older students, but increasingly for all students regardless of age, this condition created tensions and frustrations.

Against the background of this ambivalence, two further factors led the college student culture into an increasingly bitter sense of opposition to the larger society. One of these was affluence. Most college students have grown up in the greatest affluence and freedom from the discipline of hard and unremitting work of any generation in man's history. Life, at least in its material aspects, has not been difficult for them, and they have thus found a great deal in the larger society, oriented as it is to work and production, that seems needless or strange.

That students increasingly rejected this larger society, and rejected it passionately and in the name of moral principle, was the result of a second factor. The college students among whom the youth culture and campus unrest emerged were principally those from affluent families whose parents were liberals or radicals, and who attended the larger and more selective universities and colleges. They were part of the first generation of middle-class Americans to grow up in the post-depression American welfare state under the tutelage of a parental generation which embodied the distinctive moral vision of modern liberalism. Insofar as these students learned the lessons that their parents and their experiences taught, they became, inevitably, more liberal than the older generation, which had grown up in a harsher time.

The parental generation's liberalism expressed itself most characteristically in the belief that their greatest personal fulfillment came not from work, income, power, or social status, but rather from the purely non-vocational pursuits of life—the activities of living well, and the rewards of identifying with right principles applicable to the society as a whole. They pictured work, money, discipline, and ambition to their children as having little intrinsic merit and as deserving correspondingly little praise. It was instead the high-minded virtues, such as compassion, learning, love, equality, democracy, and self-expression, which they found worthy of respect and pursuit.

Not a few among this older generation believed that they managed to live in accord with this hierarchy of values. Considering the decency and comfort of their lives, it is understandable that they could entertain such hopes. But whether for reasons of modesty, or because of aspirations for higher things for their children, they persistently passed over the fact that their own comfort was usually the fruit of hard work and self-discipline.

If the parents held views which did not justify or reflect their personal history of work and self-discipline, the children, brought up in conditions of affluence and freedom from worldly struggle, adopted those views not only as attitudes but also as habits of life. They began to live, in short, what their parents mostly preached. And as they brought their parents' high-minded ideals to bear upon American society in a thoroughgoing way, their vision of that society changed radically.

The parental values were strongly reinforced in the elite universities by the liberal values of faculty members. That faculty members began to have and to transmit such an outlook was the result of another development within the university community—the professionalization of the academy, by which professors became more mobile, more independent of the university administration, and more oriented to research and publication, and as a group, more ethnically diverse. As a result, the student subculture, particularly in the more selective schools, came to be far more liberal than the subcultures of other students or of the general population.

As higher education expanded, more and more students took the values of liberal idealism as their code and habit of life. As they did, more and more students found themselves increasingly in opposition to the larger society, which did not embody these values nearly as much.

The student subculture reflected and, as it coalesced, magnified these changes of perception and value.

The thoroughgoing idealistic liberalism of the student generation of the 1960s was the ideological beginning point of the student movement and of campus unrest as they exist today. It predisposed many students to oppose the Vietnam war, to react with fury over the use of police power to quell student disturbances, and to enlist themselves in wholehearted support of civil rights and the movement for black pride.

The UniversityAs an Object of Protest

As the mid-point of the 1960's was reached, campus unrest became more and more radical in character. Indictments of race discrimination and of the war grew more sweeping and soon encompassed the university, which itself became a major target of protest. "University complicity" proved to be a powerful issue with which to mobilize students.

Polls of student opinion do not, in fact, indicate widespread discontent with higher education. A winter 1968-69 poll revealed that only four percent of seniors and two percent of freshmen found higher education "basically unsound— needs major overhauling." Fifteen percent of freshmen and nineteen percent of seniors said, "not too sound—needs many improvements." Fifty-six percent of seniors and forty-nine percent of freshmen found higher education "basically sound—needs some improvement." And nineteen percent of seniors and thirty-two percent of freshmen voted for "basically sound—essentially good."

A survey in the spring of 1969 found that only four percent of college students noted strong approval, and four percent moderate approval in response to the statement, "On the whole, college has been a deep disappointment to me." In response to the statement, "I don't feel I am learning very much in college," again, four percent noted strong assent and thirteen percent moderate assent. However, in response to the statement, "American universities have largely abdicated their responsibility to deal with vital moral issues," nine percent indicated strong assent and thirty percent moderate assent.

These surveys suggest that most American students are not fundamentally discontented with their college and university education. But substantial numbers do seem to disapprove of their schools as moral institutions.

Those who feel that the universities have failed them in some larger sense are often the children of liberal middle-class families, well prepared to do college work, and with the highest expectations of their colleges. "Why is it that the university has become the special target of so many of the very students who might be expected to find an institution devoted to the life of the mind particularly worthy of respect?

Partially, the answer may be found in the observation that Americans today have higher expectations of the university than they do of practically any other social institution. It is expected to provide models, methods, and meanings for contemporary life. It is an adviser to government and a vehicle for self-improvement and social mobility. Indeed, since science and critical method are enshrined in the university, it occupies a place in the public imagination that may be compared to that of the church in an earlier day.

It is precisely because of these high expectations that the university has forfeited some of its authority and legitimacy in the eyes of many "moderate" students. For radicals, perhaps, the university, as a part of the established society, may never have had much authority or legitimacy. But without the support of moderates, militant disruption could never have become a nation-wide problem. The "moderate" campus majority makes common cause with the militants, because student rebellion is not merely a crisis at the university. It is equally a crisis of the university itself — of its corporate identity, its purpose, and its justifications.

Despite the sophisticated style of many bright young people today, the freshman still looks forward to the great freedom and variety of college and anticipates the excitement of serious study and personal growth within a community of students and scholars. And if he does not expect it when he arrives, he learns to demand it once he has been there a while.

According to the professed culture of the university, the principal values against which any activity or vocation are to be measured are justice, compassion, and truth. The rewards of such endeavors are pictured to be intellectual excitement, personal fulfillment, and a sense of having done something worth-while. As the academy sees itself, these are the rewards of the scholarly life itself, and the basis of the sense of community within the university. Thus, the student's expectations are raised even higher as he is integrated into university life and becomes acquainted with its distinctive values.

But it is usually not long before he realizes that college life bears little relation to his expectations, and that the university itself is often quite unlike what it pictures itself to be.

Far from being a "community of scholars," the large university today is much more like a vast and impersonal staging area for professional careers. Anxious to maintain their professional standing and not unresponsive to financial inducements, the professors appear to the freshman more like corporation executives than cloistered scholars. What these professors teach seems less the humane and civilizing liberal education the freshman anticipated than a body of impersonal knowledge amassed and accepted by an anonymous "profession." The student's role in this process of education is largely passive: he sits and listens, he sits and reads, and sometimes he sits and writes. It is an uninspiring experience for many students.

This is especially the case because the contemporary youth culture is so very different in its quality and intentions. For while that culture does value the life of the mind, it also places high value on the truth of feeling and on the cultivation of the whole person. This basic attitude is not easily reconciled with the idea at the heart of the modern university that a scholar's proper work is the pursuit of probable truth — a goal that lies outside the preferences and tastes of the man who pursues it and that imposes a stringent discipline upon him. Because this academic method is the very antithesis of the style of the youth culture, large numbers of students today are ill suited to university life and its academic pursuits.

Student reactions to higher education vary. Radicals increasingly express a desire to reorganize the university in order to have it act upon their own political convictions and programs. Others, less certain of their goals, seem to accept their personal disappointment or disinterest until an issue emerges on campus which symbolizes to them the university's "complicity" in social evils, or its "hypocrisy" about its aims and practices.

The moral authority of the university was compromised as a result of its expansion and professionalization after World War II. For as it expanded, higher education in America changed. But these changes had primarily to do with physically accommodating the huge influx of students, with meeting the increasing variety of demands being made upon the university by government and business, and with satisfying the ever-increasing appetite of the faculty for freedom, including the freedom to do things other than teaching. By the mid-1950's, universities were permitting faculty to accept research grants which, in some instances, were larger than the operating budgets of their entire academic department.

As a result, new men of power walked the campus. Recognition for distinguished teaching and scholarship in the traditional manner, which rewarded knowledge pursued for its own sake, so that a medievalist might be as highly regarded as a chemist, became increasingly rare. Certainly, knowledge for its own sake was still admirable, but scholars now could also hope to achieve wealth and power for proposing technological and political solutions to the problems of industry and government — and this cast doubt upon the university's claim that it was a center for disinterested research and teaching.

Are there any reforms which might solve the problems arising out of the university's loss of moral authority? The question has produced a serious debate in colleges and universities across the country, but no clear answer.

Some suggest the colleges and universities should relate themselves more fully to life around them, and thus respond to the demand for relevance. Others suggest they should withdraw further, and thus free themselves from the taint of involvement with an impure society and government.

Some argue strongly that colleges and universities must make every effort to restore as soon as possible a meaningful core curriculum which would socialize youth into society and provide the basic education that any citizen should have. Others assert that it is impossible for any modern university to agree on what such a curriculum should be, and that even the modest efforts of the colleges to provide a core curriculum should be abandoned as intellectually and culturally arbitrary.

Some have emphasized that the most serious educational failing of the university was to dilute its teaching function and to disorder its moral priorities with too great an emphasis on research and on establishing links to government and business. Others insist that the research emphasis and even consulting improve the university—and specifically improve the quality of teaching—by bringing it in closer touch with the frontiers of knowledge and with the practical needs that occasion research.

The Commission engages in no rhetorical evasion when it places against each interpretation largely contradictory interpretations of just what in the colleges and universities has led to the crisis and what, therefore, should be reformed. All these positions can be argued persuasively, and specific proposals for reform are as numerous as they are controversial.

Still, without attempting to endorse a particular point of view, we do think it can be said that some of the causes of student unrest are to be found in certain contemporary features of colleges and universities. It is impressive, for example, that unrest is most prominent in the larger universities; that it is less common in those in which, by certain measures, greater attention is paid to students and to the needs of education, and where students and faculty seem to form single communities, either because of their size or the shared values of their members.

The Escalation ofCommitment and Rejection

The emergence of the great issues of our time, the evolution of an oppositional college student subculture, and the changing nature of the university have all contributed to the development of campus unrest. Yet as we emphasized at the outset, these are no more than contributing causes. They explain—at least they suggest—the general direction in which opinion on campus was likely to move. Yet they do not suffice to explain why campus unrest developed at the time it did, or with the speed it did. Neither do they explain why tactics changed as they did.

We also pointed out at the onset that the direct functional cause of campus unrest has been the free existential act of commitment which each member of the student movement has made to a particular political vision, to the practice of expressing that vision publicly, and to particular acts of protest. To say this is to state more than a simple deductive truth, for an activist mode of expressing political opinion has important consequences for the development of that opinion itself.

Studies of activist youth reveal that in most cases students become activists through an extended process. They encounter others who are politically involved, assimilate their views, reassess their own thinking, engage in some political action but make no conscious decision about what their politics will be, or how far they will go in pursuing activist modes of political expression. At some point, however, they discover that they have changed in some qualitative way, that they are no longer what they were, and that they are now "radicals" or "activists."

This discovery often provokes or heightens in the activist a sharp sense of commitment to act in behalf of his vision of a just society. As he pursues such action, and especially as he does so in the face of opposition, his sense of commitment often grows. So, too, do the consciousness and decisiveness with which he chooses to commit himself to specific acts of protest.

These spiraling acts of will and choice lead the activists to reject the society which harbors the evils he commits himself to extirpate. For each act of commitment is a promise to make any necessary sacrifice to demonstrate against social evils and to promote justice. Over time, these acts of commitment amount to a conscious decision to alter one's ways of thinking and acting, and to pursue some vision of a good society in an activist way. And thus, over time, they define the activist as one in an adversary relationship to the larger society.

Such acts of commitment may be compared, in their total effect, to sudden and intense religious conversion, through which an individual perceives anew the evil in the world and dedicates himself to the way of righteousness. For there is in the character of radical protest an almost religious fervor, as there has been in other college movements in other nations in other times. The religious parallel suggest itself, too, for the way it illumines the problem of responding to campus unrest. For just as it has never worked to send guns—or lions—against religious converts, so too has it been unavailing to meet campus activism with force. Force only tests the mettle of the activist's commitment, and thus ends not by weakening the movement but by strengthening it.

The idea of commitment is central to an understanding of campus unrest in part because it accurately describes why a demonstration happened when it did. In a very real sense, the answer is that it happened because, for whatever complex or even accidental reasons, somebody or some group decided, against the background of a general vision of the good society and of effective political action, to commit himself or itself to a particular act, in a particular place, at a particular time.

Thus, a radical commitment is as much a commitment to the act of protest itself as it is a commitment to certain positions on the issues and to a certain moral vision. Where issues are not compelling, there still may be protests. The upward spiral of protest reflects the intentions of the protesters as much as the circumstances and objects of his protest.

The notion of commitment helps to explain the escalation of tactics which occurred during the 1960's. For the radical commitment contains built-in dynamic processes which, in reaction to resistance, make opinions and tactical actions even more radical.

Finally, students increasingly discovered that each issue was neither single nor simple. Once a student made the decision to be active, he became aware of the connectedness of all issues; and the more he saw, the more convinced he became that his stance was valid.

The University Environment

A university campus is an especially favorable place for those who wish to make such a commitment, for students and faculty can consider committing themselves in the almost certain knowledge that the act of commitment has no severe personal costs attached to it.

White students generally are freer than black students, non-students, and older people to act because they are subject to fewer competing commitments to family and job, and because what job requirements they do have can be put aside at relatively little cost. This is also true of professors. But students especially may drop out of school, put off their studies for short or long periods, and delay taking examinations, without paying a great price.

The relative freedom of students to act without fear of immediate serious consequences is reinforced by the partial survival of the custom of treating students as adolescents who may be forgiven their errors. Students also benefit from the historic idea of university sanctuary, which would bar police and civil authority from enforcing law on campus except in extreme circumstances. Such norms, while never having the sanction of law in the United States as they have in other countries, have still had an influence.

Moreover, the erosion of the sense of community on many campuses has meant that fewer of the informal social controls work to deter students from engaging in new or unusual modes of behavior, even ones which may harm the university. There is less traditional school spirit, fewer personal relationships, more anonymity—and, therefore, fewer personal costs involved in the commitment to engage in radical action, or even in the decision to use the university as a means of furthering political ends.

Formal controls within the university —especially university disciplinary systems—have also grown weaker. At many universities today, students encounter little formal deterrence because university administrators and faculties have often failed to punish illegal acts. In part, this has been a result of their sympathy to student causes. It is certainly due as well to the feelings of outrage on the part of faculty members over the use of force against students by the police.

Just how sympathetic faculty members are to student unrest was suggested by a comprehensive survey conducted by the American Council on Education during 1967-68. It found that faculty members were involved in the planning of over half the student protests which occurred. (The vast majority of such protests were, of course, lawful and peaceful.) And in close to two-thirds of them, faculty bodies passed resolutions approving of the protest.

The more general reason for the failure of the universities to preserve order and to discipline those who were disruptive or violent was that power in American universities is limited and diffuse. Their disciplinary and control measures were set up on the assumption that the vast majority of faculty and students would be reasonable people who would support reasonable actions on common assumptions of what is reasonable, and that this majority would accept and support the specific goals of the university. These assumptions have become increasingly unrealistic.

Finally, the campus is a favorable environment for the growth of commitment and protest because the physical situation of the university makes it relatively easy to mobilize students with common sentiments who are disposed to political action. Their numbers serve to protect them from the isolation and criticism they would experience if they were dispersed throughout the larger society.

The increase in sheer numbers of students in the United States has magnified the significance of this fact. Only a small percentage of students on a campus of 20,000 or more are needed to create a very large demonstration. Thus, in 1965-66, although opinion polls indicated that the great majority of students still supported the Vietnam war and that antiwar sentiment was not more widespread among students than among the population as a whole, opposition on campus was able to have a disproportionate public impact because it was readily mobilized for protest demonstrations. Relatively small percentages of large student bodies have constituted the "masses" occupying administration buildings or bringing great universities to a halt.

Protest itself has become an activity accepted as proper and even honorable by the general student body. Students who are not participants in an act of protest will usually take no step to impede it—except sometimes in cases where violence is involved—and will seldom assist in imposing punishment upon their fellow students....

Revolutionary ChangesIn Western Society

The final body of contributing causes of student unrest is the most difficult to formulate. These are certain broad, evolutionary changes occurring throughout the Western world, which has become a series of ever more complex interconnected societies, organized in large scale urban complexes, dependent on an increasingly sophisticated technology, dependent upon education and especially upon the university, and increasingly susceptible to general immobilization or breakdown flowing from even tiny disturbances in any of its many subunits.

These long-range changes in society have created deep disaffection among youth, not only in the United States, but in most other Western countries as well. This wave of unrest has occurred while these societies are engaged in repairing many of the defects and evils for which social critics attacked them in the past. They are withdrawing or have withdrawn from their overseas colonies. They are engaged in extending the welfare features of their societies. They are giving increased attention to the problem of equality in income and in education. Thus, we do not deal with any simple revolt against the "evils of capitalism," as may be indicated by the fact that, in other countries as in this one, it is a revolt of middle-class rather than working-class youth.

What we face is a revolt among educated youth against certain features of liberal capitalism—especially "the affluent society." There is growing opposition to the emphasis on material goods. Thus, French students proclaimed opposition to a "consumer" society, and American students, by their dress, their attitude to material goods, and their direct statements, also express opposition to their society's emphasis on consumption. This opposition is not yet fully consistent, for critics of consumer society also see as one of its chief defects its failure to supply sufficient consumer goods to some strata of society. Nevertheless, the consumer goods criticism is real and strongly felt.

We may also print to a nascent—if still largely implicit—opposition to democracy which is beginning to receive serious formulation by some political theorists. The youth most active in the unrest now tend to feel that determination of political representation or policies by simple measures such as one man one vote may be inadequate, and that the human qualities of the representatives and policies thus adopted must play a role in their acceptance. A rather elaborate critique of democracy from the left has been developed by one contemporary radical philospher, Herbert Marcuse, and he and others have also attacked the virtue of tolerance in the present society.

A third aspect of what we might call Western capitalist, liberal society to which many young people are now hostile is the emphasis on effort, disciplined work, and the mechanisms that encourage it and reward it. This is seen in the insistence that everyone should do "his own thing" and more that he should not suffer for it.

It would be an illusion to see this as being directed simply against some of the errors of this kind of society. This attack is directed as strongly—even more strongly—against those features of this kind of society that most of us consider virtues: its capacity to improve the material condition of people; its dependence on democraey and tolerance; its capacity to evoke work and effort and to reward work and effort.

Thus, the possibility cannot be over-looked that the true causes of the events we today characterize as "campus unrest" lie deep in the social and economic patterns that have been building in Western industrial society for a hundred years or more. It is at least remarkable that so many of the themes of the new international youth culture appear to revolve in one way or another about the human costs of technology and urban life, and how often they seem to echo a yearning to return to an ancient and simpler day.

End Note

Our theme in this chapter has been that the root causes for what we call campus unrest are exceedingly complex, are deeply planted in basic social and philosophic movements, and are not only nationwide but also worldwide.

Given this view of the matter, how should the United States, and American society, deal with the problems of campus unrest, react to them, respond to them?

First, much good can be done through more understanding and better understanding. Substantive differences divide the proponents of the new culture from those of traditional American society. Superficial differences in style also separate them. But in addition to these differences, unnecessary tensions emerge from simple misunderstanding of one another. A large crowd of students may well appear threatening to others when it is in fact a normal gathering for communication. Language that affronts, may have had no such intent. The university administrator who seeks to explain how and why a particular decision was made through a complex series of committee decisions is not by that fact giving a bureaucratic runaround to his inquirer. Understanding does not obliterate differences. But understanding can reduce incidents and clashes and the risks of greater distrust and violence.

Second, teachers, scholars, and parents may well find many of the adherents of the new culture to be inexperienced in affairs, impatient of explanations, uninformed about the world, rude and arrogant in their self-righteousness, and insufficiently alive to the importance of other vital principles and ideals that are not central to the new culture. The only answer here is to seek to teach, to educate, and to inform. And in turn, the students will be found to have the capacity on some matters to educate and enlarge the perspective of the older generation.

Beyond that, it must be stressed again that much of what is commonly called "campus unrest" is not a problem. It is a condition. If a generation of American students are emerging to full adulthood affected in varying degrees by a different world view and a different set of values, accommodations to their perspectives can be made only over a long period of time and through the operation of the political process. In that case, we can only hope, and try to insure, that the American political system will continue to assist the peaceful coexistence or blending of different lifestyles.

Student artist Steven H. Singer '72 interprets the mood of modernyouth, alienated from a society which he views as confining him.

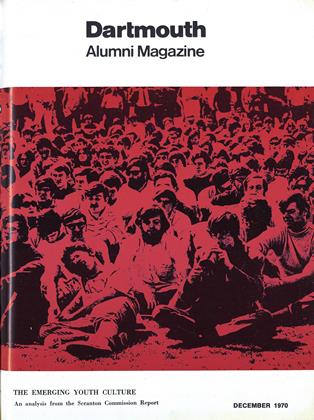

THE REPORT of the President's Commission on Student Unrest, generally known as the Scranton Report, is "must" reading for anyone connected with or interested in American higher education. Of the seven main chapters of the report, the one devoted to "The Causes of Student Protest" is so perceptive and so excellently done that we consider it important to bring it to the attention of Dartmouth alumni, only a small portion of whom would otherwise see it. Campus unrest has bewildered most alumni and polarized some. The Scranton Report calls for greater understanding on all sides, and in an effort to contribute to that understanding we here reprint what we consider to be a balanced and enlightening chapter on the new youth culture.

"Surveys suggest that mostAmerican students are not fundamentally discontented withtheir college and university education. But substantial numbers do seem to disapprove oftheir schools as moral institutions."

"It is impressive that unrest ismost prominent in the largeruniversities; that it is less common in those in which, by certain measures, greater attentionis paid to students and to theneeds of education, and wherestudents and faculty seem toform single communities . . ."

"The relative freedom of students to act without fear of immediate serious consequences is reinforced by the partial survival of the custom of treating students as adolescents who may be forgiven their errors."

"What we face is a revolt amongeducated youth against certainfeatures of liberal capitalism especially the affluent society.There is growing opposition tothe emphasis on material goods."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Outward Bound Term

December 1970 By Robert B. Graham Jr. '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

December 1970 -

Article

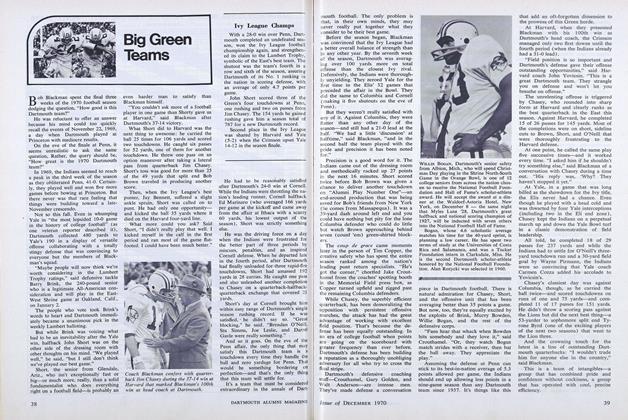

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1970 By CHRISTOPHER CROSBY '71 -

Article

ArticleRamon Guthrie's New Poem

December 1970 By James M. Reid '24

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFather Prior

OCTOBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

JUNE 1967 By C.E.W. -

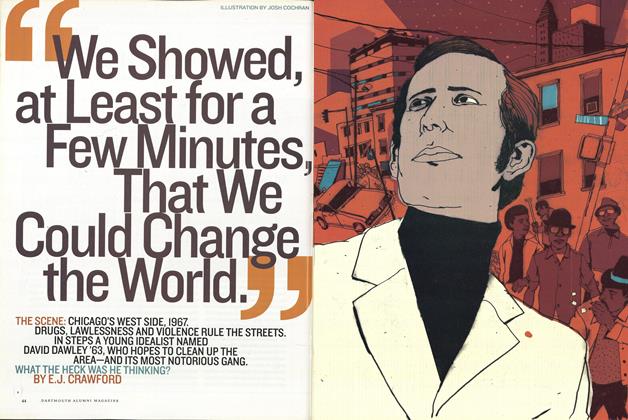

Cover Story

Cover Story“We Could Change the World”

May/June 2008 By E.J. CRAWFORD -

Feature

FeatureSlade Gorton

Jan/Feb 2003 By JENNIFER AVELLINO ’89 -

Feature

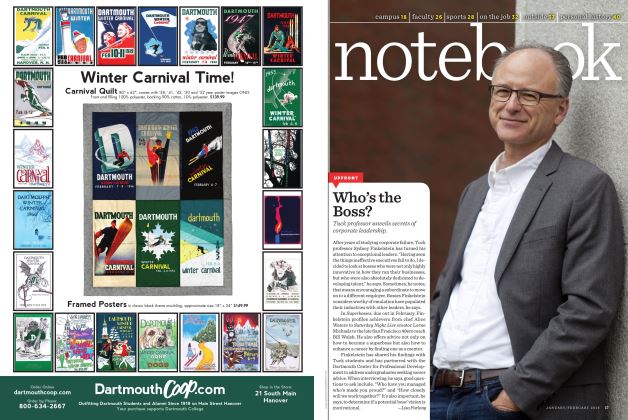

Featurenotebook

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By LAURA DECAPUA PHOTOGRAPHY/TUCK