More on Shockley

TO THE EDITOR:

It angers most Americans to hear their country described as a racist society, and yet there were several excellent examples in the December "Letters to the Editor" section under the headings "The Shockley Incident" and "The Indian Symbol" which demonstrate why it is often described as such. They pointed out to me the subtle forms which racism takes in our predominantly white society. The chief objection I have to this type of outburst of feeling toward an incident with racial overtones is that it is written by a White American to White Americans without any real consideration of the feelings of Black Americans or American Indians involved in the incidents. Had the writers had the opportunity to discuss either the "Shockley Incident" or the abolition of the Indian-cheerleader with a black student or an Indian student in a one-to-one situation, I would bet that their tones would have differed from their letters.

I do not wish to justify the "Shockley Incident." Only 17 of the approximately 160 black students currently on campus were finally convicted of denying Mr. Shockley the .right of free speech. (A total of 30 or more students took part in the incident, but many stopped clapping upon the request from Dean Brewster.) There was certainly not agreement among black students on campus before, after or during the incident about whether the "clap-down" was "right," but one thing was clear. It was an emotionally charged atmosphere in which the students felt that the proposed speaker was about to lash out at their race in a degrading fashion. Contrary to implications in several of the letters, it wasn't just the least intelligent or most boorish students who took part. Proud and stubborn, yes; boorish, no.

With regard to the downfall of the Indian-cheerleader, I must admit that upon first hearing of this decision I too felt a pang of nostalgia for bygone times, because I had acted as the Indian-cheerleader during the 1962 football season. "I always attempted to be a proud Indian," I thought, "why should these students feel offended?" This was my white, middle-class upbringing coming out, however. It has since been pointed out to me that to an individual who identifies with a race which is just evolving its race pride in modern America it touches a raw nerve to see a non-Indian pretending to be one and cavorting as a mascot at a football game. To equate the Indian with the Columbia Lion or the Princeton Tiger is not upgrading the Indian race. Once again, the writers missed the point. The students were not asking that the "Dartmouth Indian" name or the profile on letterheads be eliminated. The objectionable part was making the Indian a mascot instead of an equal human being.

I don't mean to insult the individuals who wrote these letters in good faith, but we must all attempt to put ourselves in the other person's position in order to understand him. If we are to decrease the pressures of racism in this country and the world, we must attempt to look further than college loyalties or national loyalties to "human loyalties."

Hanover, N.H.

TO THE EDITOR:

The work of Dr. Shockley and Dr. Jensen, as I understand it, is an attempt to prove that people of different races inherit genetically, as a race, different intellectual capabilities which produce different personality traits. It is argued, then, that behavior is more the result of genetic factors than upbringing, education, and other environmental influences. At least two Dartmouth graduates appear to accept this idea that behavior is based on birth. Edwin D. Neff '35, writes, "Meanwhile, there is the suggestion at least that their (the Black Students') behavior answered the question Dr. Shockley raised better than the paper he could not present," and W. Bradley Morehouse '46 says, "It's a pity that the black boors who prevented Dr. Shockley from speaking last week should have given some credence thereby to his unfashionable views." (DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, Dec. 1969.)

Both these statements are classic examples of racial prejudice: unscientific and limited observation, generalization to the whole race, and then jumping to the conclusion that the cause of the behavior is genetic. The use of controls is also omitted. If either of these observers had been in Washington on November 15 they might have altered their theories about the genetic causes for mass protest. One suspects that Dr. Shockley's techniques, while much more sophisticated, are really subject to the same weaknesses.

I assume that the behavior trait that Neff and Morehouse now want to ascribe to Black people is a genetic anarchy or rebelliousness. It is peculiar that the same race could change so rapidly in just a little more than a century from the time when slave owners, observing their slaves carefully, commented on the docility of Black people. I suppose this change must be the result of the mongrelization of the races, or something.

There is a theory held by many Black Muslims, and described in the Autobiography of Malcolm X, that white people are born racist and without soul. Malcolm X, in the early days of his conversion to the Muslim belief, used the term "White Devils." There is, I'm afraid, ample evidence in support of this theory that can be found by observing slavery, Vietnam, and now the alleged atrocities against the Black Panthers in Chicago. To use the logic of Neff and Morehouse, it is a pity that they, and millions of White people like them, give credence to this view of genetic White racism.

Saxtons River, Vt.

TO THE EDITOR:

Being one of "certain alumni" whose letters regarding the Shockley affair Mr. Alan Gettner found overtly racist in character, I would like to assure Dartmouth readers that I have no prejudices against any group or class of people.

As proof of my openmindedness, may I point out that one of my best friends is a research instructor in philosophy?

Northfeld, Vt.

TO THE EDITOR:

I would like to refer to the Editor's Note in the December issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, answering an alumnus' letter about the Shockley incident. At a time when the case was not adjudicated by either the Black Judiciary Committee or by the CCSC, your note states that "in the College's view" the students "violated the principle of free discourse." I fail to understand how "the College" can state as a matter of fact that the students violated College rules before the case had been either heard or decided. In my opinion such a statement amounts to an unacceptable interference with a pending procedure and a presumption of guilt as well.

Professor of Government

Hanover, N.H.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The statement to which Professor Ehrmann objects was based on the view publicly expressed by Provost Leonard M. Rieser, speaking as a College official, but we concede that it would have been better had we made it clear that it was he and not "the College" speaking. As for interference, the December issue appeared on the day the CCSC rendered its decision.

Response to Two Letters

TO THE EDITOR:

Two letters" in your January issue invite comment:

(1) Robert M. Gippin '69, an undergraduate member and also chairman of the student-faculty committee which in 1967-68 framed the Guidelines (later adopted as Policy) on Freedom of Expression and Dissent, finds that the College's response to the Parkhurst takeover was "a perversion of the intent of that policy." I was a faculty member of that same committee, but I do not share Gippin's view. The College took enormous pains to assure the expression of all possible points of view on the ROTC issue, over a period of weeks. It was the response of the militant minority, not the response of the College, which alone violated the Policy.

Gippin remarks on the College's "haste in turning to the State's police power." He should recall that President Dickey had, at least a week earlier, expressly announced his intention to seek an injunction if Parkhurst were to be seized. Moreover, the Faculty vote of confidence in this policy was overwhelming if not unanimous. And it cannot be denied that all physical violence and pain were averted. Alternative policies could not easily be guaranteed to have done so.

The question of double jeopardy has been raised by many; but it is possible to hold the view that the College and the State were really not concerned with the same offense. Attendance at Dartmouth is still a privilege, not a right.

Nobody can be happy over the Parkhurst incident, except possibly William Loeb. On balance, however, I think the alumni can feel gratified rather than ashamed at the way things turned out.

(2) Alan Gettner of the Department of Philosophy apparently thinks that the National Academy of Sciences "gave Dr. Shockley a prestigious forum without arranging for a rebuttal." Either Gettner was not there, or his memory needs a jog. The Academy "gave" Shockley nothing. As a member, he has the constitutional right to present a paper at any Academy meeting, and there was no way to keep him off the program. As chairman of the meeting at Dartmouth, I followed a deliberate policy (in retrospect, it may seem, possibly not a wise one) of submerging all publicity about Shockley's paper, which was only one of some 45 talks at the meeting, and of scheduling it at the very end. My hope (which I communicated to the Afro-American Society after the Manchester Union Leader gave Shockley front-page publicity) was that people would either ignore or boycott Shockley's presentation, leaving him to address an almost empty room. However, thanks to the Leader and to a mimeographed call for action distributed by two SDS members, an overflow crowd appeared. At that point, it might have been technically possible to invoke an Academy by-law: by majority vote of the Academy members present (about five) we could have closed the session to the public. But this maneuver could also have produced a dangerous response, and I did not seriously consider it. (The Black Judicial Advisory Committee has given its opinion after the fact that I should have tried it.) Instead, I told the audience of some 200 people what the Academy rules were; that neither Dartmouth nor the Academy had invited Shockley's paper or in any way sponsored or endorsed it; that the Academy rules required time for discussion and rebuttal; and that indeed several persons present, including Professor Kemeny, were prepared to challenge Shockley's statements and debate the issue. To make the Academy's position clear, I also read a prepared statement by its President, Dr. Philip Handler, which specifically repudiated any notion that the Academy sponsored Shockley's views. Offering to clarify any of these points but hearing no requests to do so, I then introduced Shockley, with results that are now well known.

This is not the first time that Dr. Shockley has discomfited the Academy, and doubtless it will not be the last. He is formidable and determined. He has brought unpleasantness to his Dartmouth hosts as well as to the Academy. But his greatest sin is the anguish that he brought to the black students. It is they who have lost the most from this bitter affair, and it is they who should have our greatest concern and understanding.

Professor of Chemistry

Hanover, N.H.

P.S. I purposely refrain from stating here any personal opinions about the position of the Judicial Advisory Committee or the CCSC in respect to the Shockley Incident.

An Indian Graduate Writes

TO THE EDITOR:

This concerns the item in the '69 Times newsletter regarding the disappearance of the Dartmouth "Indian" at the football games. The reason for his disappearance is that I and the other Indian students worked for over a year to remove this racial slur from the Dartmouth campus. In our struggle to abolish this image, we encountered many people who had been blinded to the prejudices involved. Their most common defense in these confrontations was, "There's nothing wrong with it. It's an inoffensive and proud symbol of the Indian. You should be proud of the fact that is represents Dartmouth."

Clearly, this image is inoffensive to these people, but to the people it represents it is only a humiliating reminder of the subordinated position the Indian holds throughout American society. Furthermore, our people resent having a non-Indian masquerading as an Indian, an act which only serves to exploit our cultural heritage and traditions for a white man's gain and our embarrassment and indignation. To say this is a noble symbol of my forebears only confuses the issue by identifying it with a highly romanticized fictional character. The problem lies in the fact that this mythical creature continues to be propagated by any number of sources. In fact, the continuing use of such an image is probably more harmful than the stereotype it has largely replaced, namely, the "bloodthirsty savage."

This unfortunate symbol is much akin to the manner in which Blacks have been recognized by ignorant people as being naturally good dancers and athletes. When a people as a group are recognized as dancing, musical performers, or quiet, noble painted and feathered warriors, they are being denied the right of being recognized and treated as human beings. It is simplistic to say that "of course we realize that all Indians aren't like that," when we Indian people are all too well aware of the fact that we have never been and still are not portrayed as we really are.

The many alumni who are "concerned" over the loss of the "Indian" represent an attitude which we found to be expressed in questions like, "What right have you to destroy Dartmouth's traditions?" I can only hope these concerned individuals put their Dartmouth educations to better use than they evidence in attitudes such as these.

Rochester, N.Y.

Historic Moonlighting

TO THE EDITOR:

The December issue is wonderful. Eleazar Wheelock comes more and more to life. We have had to wait too long. The Reverend Ebenezer Cleaveland, my great-great-great-great-grandfather, scouted the location of the College. He, also, was moonlighting as his church in Rockport could not keep up his pay. I think of Dartmouth College as the product of the greatest moonlighting of the 18th century.

St. Petersburg, Fla.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom the Primate Patrimony To the Fellowship of Flowers

February 1970 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ, -

Feature

FeatureThe Pros and Cons of Coeducation

February 1970 -

Feature

FeatureSpeaking of Books

February 1970 By FRANCIS BROWN '25, -

Feature

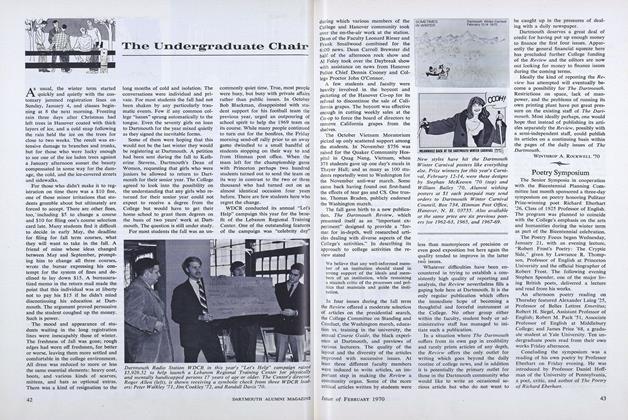

FeaturePROF. JOHN G. KEMENY CHOSEN AS DARTMOUTH'S 13TH PRESIDENT

February 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1970 By EDMUND H. BOOTH, DONALD L. BARR

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorTHE MEMORIAL ARCHWAY TO MEMORIAL FIELD

May, 1923 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MARCH 1930 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

April 1955 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

December 1955 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA Procrastinated Holiday

FEBRUARY 1994 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorReaders React

July | August 2014