ONE of the major sessions of the joint meeting of the Board of Trustees and the Dartmouth Alumni Council, held in Hanover on the weekend of December 12-13, was devoted to an interim report by the Trustee Study Committee on Coeducation, headed by Trustee Dudley W. Orr '29, chairman, and Provost Leonard M. Rieser '44, co-chairman.

The main presentation was made by Prof. John G. Kemeny, chairman of the subcommittee on academic models, and is printed here in full. Briefer statements were made by Mr. Orr, Dean Rieser, and William H. Timbers '37, president of the Alumni Council; and the whole committee participated in the discussion which followed.

In addition to the four speakers, the Trustee Study Committee on Coeducation includes Trustee Charles J. Zimmerman '23; Joseph J. Palamountain '42, President of Skidmore College; Treasurer John F. Meek '33; Dean Carroll W. Brewster; James A. Davis, Professor of Sociology; Mrs. Reese T. Prosser, Lecturer in History; Thomas Vargish, Assistant Professor of English; Sanford B. Ferguson '70; Leonid A. Turkevich '71, and Daniel Cooperman 72. Assisting the committee in substudies are other faculty members and students, including four coeds now at Dartmouth in the exchange program.

Mr. Orr

WHY, at this time are we studying the subject of formal coeducation as part of the academic program at Dartmouth College?

There are three reasons for doing so. First, it is part of the tradition of Dartmouth College to respond to the aspirations and values of the society of which it is a part. When Eleazar Wheelock founded the College 200 years ago, it was a response to what the people at that time thought was needed. If Eleazar were founding a college today, I think it probably would be coeducational, because 19 out of 20 collegeage men and women in America are in coeducational institutions. Coeducation is the rule; we are the exception. This fact is associated with a couple of other facts of our times. The past 25 years have been a period of tremendous change both in American society and in social and political arrangements all over the world. One part of this great change has been a change in the status of women and in the attitude of people towards the relationships between men and women. These things added together suggest that an institution like Dartmouth, in order to maintain its eminence, must consider the possibility of coeducation as part of its formal educational program.

There are at least two other reasons for studying coeducation. It is perfectly clear that the students and faculty are in favor of coeducation, although they might emphasize different reasons for it. The students tend to emphasize the social aspect of coeducation whereas the faculty puts more emphasis on what they consider to be its educational advantages. The final reason for study is the fact that all of a sudden our principal competitors have gone into the business. If we were in the milk business and we saw that all our competitors were going into the ice cream business, we would be imprudent if we didn't see what there was in the ice cream business for us. And that's the situation that Princeton and Yale have put us into. I don't want to push this analogy too far, however, because the mere fact that Macy's sells a full line of women's apparel as well as men's doesn't necessarily prove that Brooks Brothers should do the same thing.

There are a number of other things to be said on this topic. There is the question of who is making this study, and there is also the question of how this study is being made. The Provost of the College, whom I am about to introduce, will supply an answer as to who is making the study and, perhaps, make some additional observations before we come to the question of how the study is being conducted.

Dean Rieser

I WON'T have to tell you, because it will be obvious, that our work is in a very preliminary stage; it is our aspiration to have some kind of a report to give the Trustees in June.

Dudley Orr has already made observations on why we are engaged in these considerations. One's reaction is: Well, why not leave well enough alone? We've become aware of some things he has mentioned and I will mention several others to you. First of all, no significant institution now limited only to men or only to women has been established in the 20th Century. And secondly, few colleges or universities are as entirely dependent on themselves, on their own community, as Dartmouth is. Indeed, we take pride in this self-sufficiency. And certainly few if any of the top educational institutions in this situation have found it wise to educate at this time 18- to 22-year-old men, separate from women, for a period of four years.

Now this collective judgment certainly does not require that we change, but it does require that we not ignore the competitors in this business, and that we consider it rationally and make a hard-headed decision which is relevant for our era. Indeed, I might simply read to you the charge given to us by the Trustees when establishing the committee: "To undertake a comprehensive and concrete examination of Dartmouth's total existing and prospective program developments for the decade of the '70s with particular attention to a study of the question of the education of women at the College."

The only additional thing I want to do is to ask some questions, the kind of questions that weigh on us.

First of all, can the most meaningful education of a highly select group of contemporary male secondary-school graduates take place in Hanover for four years in the presence of men only, given the life-style which these students have adopted and which society has accepted?

Second, are there arguments for maintaining a men's institution which would not justify founding one, but nevertheless are sufficiently strong as to preclude giving one up? It's clear that nobody is founding one these days, but society is founding very few if any private institutions, and public institutions would have a hard case to make to the state legislature to exclude one sex or the other.

Third, would Dartmouth be stronger if Smith were within walking distance? That's not an arrangement we have in mind; I simply mention it as one different way of thinking about the issue.

Fourth, are the men who will reject Dartmouth because it does not provide the opportunity to study and live in a community with women, students whose absence would really concern us?

Fifth, is it conceivable that in the year 1980 all institutions, not just educational institutions, but all institutions, will have eliminated sex as a consideration for membership?

Sixth, if we were to commit ourselves to the education of both men and women, what opportunity is singularly available to us in Hanover with professional schools, etc?

Finally, I'll raise one last question relating to our meeting here together. How can you who have attended this College, and have supported it handsomely, join in these considerations as if you were enrolled now, or teaching now, or administrating now? Because we who live here have to deal with it now, and therefore we ask you to put yourself in this situation. At the same time, many of you have a perspective gained by looking at us from farther outside. How can your perspective of this traditional institution help us, and at the same time how can we again help you look at Dartmouth with the same rationality which you demand of your self in considering your own contemporary affairs?

Professor Kemeny

TOMORROW Dartmouth College will be 200 years old. If you look at the history of Dartmouth College, it has been a history of change; a history of an institution unlike any other in the United States, or anywhere else in the world, searching for a special destiny. During no period has this change been more rapid or more progressive and successful then the last quarter of a century during the leadership of President Dickey. I think this has a great deal to do with the atmosphere on campus today. We realize that John Dickey is leaving us, creating a tremendous change for the institution. This event, coupled with the historic moment of our Bicentennial year, has created an atmosphere of soul-searching in which the number one topic of conversation on the campus is the question of priorities. I think of my 16 years here, and I can say that during the past year I've heard more discussion, particularly on the part of the faculty, of the overall question of institutional priorities, than in the previous 15 years.

Everyone has his own list of priorities and his own list of issues that must be debated and resolved. I once, as an exercise, made my own list and, if I remember correctly, there were 13 major items on it. One of the 13 was the question of the education of women at Dartmouth. I want to emphasize that this was only one of 13 major issues, but it is a peculiar one. For reasons, and I hate to speculate why, it is the one issue that creates the greatest amount of heat. No matter which side you are on, emotions rise much higher on the issue of coeducation than on any of the other issues we are trying to debate. There are many alternatives open to Dartmouth College on this issue, but we have concluded in our committee that there is one alternative that is not open to us! That is the alternative of ignoring the issue.

First let me comment about the work of the major committee, the committee of 14 people who are charged with the responsibility of making a report to the Board of Trustees. This committee has been meeting monthly in long, hardworking sessions. The number one priority of this committee is, of course, to debate the very difficult philosophical issue - the pros and cons of coeducation at Dartmouth.

I would like to comment on a few of the issues that we have considered, none of which we have resolved. I don't know why this seems to be the day when all the speakers speak about the competition. I, too, have some remarks to make on that subject. I wonder if you realize that we are probably competing in the most competitive market in the United States. You might think that when a million students enter college each year, we have a very large market to which to sell our product. However, Dartmouth is not in that market. There's the obvious fact that we are interested only in male students, but that's not the point I'm trying to make. The very significant point is that the top half of our class scores at the 97th percentile or higher in College Board scores among those students who do enter college. That means that we're trying to fill the top half of our class out of three per cent of the male students who are entering college. The number of such students is about 20,000. So first of all, we are trying to fill the top half of our class from a potential group of about 20,000 applicants. But the situation is worse than that, as has been brought out in our committee. Although Dartmouth has a very generous scholarship policy, unless two-thirds of our students can afford Dartmouth College and can pay their way through here, Dartmouth College would be bankrupt. And if you try to estimate the number of students who are both this bright and whose parents can afford a Dartmouth education, you probably come out with a potential group of 5,000 students, of whom we have to attract several hundred to Dartmouth College. Therefore, it is an extremely tight and highly competitive market and when we express worries about our competition, we have good reasons to worry.

You will find as I go along that there are equally strong arguments on both sides of almost every issue. Any move that would make Dartmouth significantly less attractive to this group of 5,000 applicants would be tragic for Dartmouth. But is this what is going to happen? Princeton and Yale have gone coed. They now have a new attraction to students. On the other hand, this makes Dartmouth unique among the Ivy League institutions as the only all-male institution. Therefore, one of the fundamental questions is: What does this do to Dartmouth's competitive position? Hopefully by next May we will have some information. We have heard that applications at Princeton are up significantly this year, but applications alone do not tell the story. The question is where do the students decide to go when they have to make that very difficult choice next spring. And we are talking about those students for whom all the institutions compete hardest- our brightest, ablest students who can afford college. So we will have some data on this in May and will have a preliminary guess as to which way this particular new attraction influences potential students. So in a way our key question here is that going coed is certainly a very dramatic move for an Ivy League institution. It certainly attracts an enormous amount of publicity; it is certainly a new product, but it is not clear at this moment whether the new product is a Mustang or an Edsel.

Secondly, we have to mention the attitude of our students, if for no other reason that in another 20 years they are likely to be a major portion of the Alumni Council at Dartmouth College. The best information we have available is a very careful survey conducted last January by members of the Sociology Department of Dartmouth College. It was an in-depth study of students' attitudes towards almost everything on the Dartmouth campus. Coeducation was just one minor issue in the entire survey. Many of the results are very interesting. Students were asked to rate, ranging from terrible to excellent, several major features of the institution and I thought you might like to hear some of the results. For example, the faculty was rated good or excellent by 95% of our students. A very pleasant result. The academic facilities were rated good or excellent by 89% of the students. The course offerings and the choice of courses were rated good or excellent by 74% of the students. Here is one I still can't believe: The food on campus was rated excellent or good by 42% of the students. And then we come to social life, which was rated good or excellent by only 12% of the students. Two-thirds of our students rated it as poor or terrible and fully 30% of them rated it as terrible.

When we turn to the issue of coeducation, 84% of all our students said that they favored coeducation, but as I said this was a very sophisticated survey and although the easy question was put first, a number of more searching questions were put in afterwards. Questions to the effect: "Would you favor coeducation if you had to pay such and such a price for it?" For example, if it resulted in larger classes, or we had to give up graduate programs, or any of the other painful choices that one might have to make. The number of students in favor then typically dropped down to 50%, which at least shows that the students are willing to think in terms of alternatives and do not just come out with easy answers to difficult questions.

Nevertheless, when they were asked to rate issues on campus, coeducation Was rated far and away the number one controversial issue on campus. And the one question in the survey that disturbed me most, even if many of the students did not mean their answer, was the question as to whether they would advise a younger brother to come to Dartmouth College if Dartmouth College stayed an all-male institution. Fifty-three per cent of our students said that they would not advise a younger brother to come to Dartmouth. I'm presenting this evidence simply to say that this is probably the hottest issue among the students on campus, and I think one of the important effects that the very existence of our committee has had is that the students are aware that this issue is receiving very serious and careful consideration and, therefore, we do .not have riots on campus on this subject. We do not have protests because the students are convinced that this committee is going to give serious and fair consideration to a very complex issue.

I would like to comment on why the students seem to feel this way and here we have evidence based on conversations with students. It is very easy to read the survey as simply saying that the students are complaining about an insufficiency of sex and no doubt this is one factor in their considerations. But I think it would be a mistake, and a dangerous mistake, to dismiss the students' feelings that simply. Again and again, both on this campus and other campuses, one hears student testimony to the effect that they are complaining precisely because the only relations they have to women students at other institutions is during a hectic weekend where sex is the major factor. They would like to be able to have pleasant social relations with women under much less strained circumstances, where friendships could be established, where you are not continually challenged, where you feel that you can establish an informal relationship. This seems to mean a great deal to the present generation of college students.

This brings us to the key issue for an educational institution. The question is: What would the admission of women do to the quality of education at Dartmouth College? And again one can hear very strong arguments on both sides of the issue. For example, we have heard eloquent arguments that go somewhat as follows: One of Dartmouth's outstanding characteristics is the fact that Dartmouth has traditionally trained many of the most important leaders of the United States in a great many different fields. One further argues that spending four years in an all-male environment contributes greatly to the training of leaders. This is certainly an argument to which we have given considerable weight.

On the other side we hear testimony from faculty members who have had experience both in all-male and coeducational environments that in many subjects (probably mathematics is not the best example of this) there is a qualitative difference in the classroom discussions in an all-male and a coeducational environment. It's particularly our colleagues in the humanities and the social sciences who have given testimonial to this, and I wonder if some of you may have had a similar experience. We know that Alumni College has been an exceptionally successful endeavor on the part of Dartmouth. And we have heard testimonials from a great many alumni who have attended it that one of the exciting features of Alumni College was precisely the fact that alumni and their wives participated together, Men and women brought quite different points of view to the same discussion, and out of the clash of different opinions the discussion achieved a much deeper level of significance than an all-male discussion would have been able to achieve.

And finally, when we talk about the quality of education at Dartmouth, we must come to the point that Provost Rieser raised: As we prepare our students for life, are we doing them justice by leaving out of their educational process an extremely important aspect of preparation for life, by depriving them of feminine companionship during a four-year period that is a significant formative period in their lives?

That brings us to the issue on which the committee is bound to spend more time than on any other, namely, the question of cost. It is one of the sad facts of life that, even should the other arguments come out in favor of coeducation, we still have to take a very very hard look at the question of what financial sacrifices would have to be made in order to make coeducation a reality; and what it might mean in terms of either giving up other programs or cutting into other programs that are vital to Dartmouth College. Somewhere we must come face to face with the basic charge of the committee: Where does coeducation fit in with the various priorities of the institution and is the price of coeducation too high in terms of other sacrifices?

In addition to struggling with these difficult philosophical issues, the committee has taken a wide variety of testimony of which I'll mention just a few. We have heard President Dickey's views on the entire issue. We have read a carefully-thought-out document from George Colton on some of the implications for fund-raising if Dartmouth goes coeducational. We have heard from Eddie Chamberlain about questions concerning admissions. We have studied at great length a report that was prepared by Princeton University when they decided to go coeducational. And we have spent part of an afternoon with a member of the Smith College faculty who has spent a year studying in depth the question of whether Smith College should go coeducational.

Now, let me show you how confusing these issues are. We had thought that we had made significant progress after reading the Princeton report and having some information on what Yale did. We realized that somehow the decision was much simpler at Yale and at Princeton because the financial considerations were not nearly so severe there. We identified two major differences between Princeton and Yale on the one hand and Dartmouth on the other that were relevant to this decision. First of all the endowments of Princeton and Yale are significantly better than that of Dartmouth College, although ours is, of course, very good. Secondly, Princeton and Yale both have made much heavier commitments to graduate education than Dartmouth College and we had a strong impression that as you build up a faculty for graduate education you somehow have more slack and freedom, you have a richer mix of faculty if I may put it that way; and therefore it is easier to work in a new group of students without having to increase the total expenditure proportionately to the number of students you have. We were very happy about that explanation of why life seems so much easier at Princeton and Yale than it does at Dartmouth. That is, we were very happy until we heard the report from Smith College, which at least so far as one member of the committee is concerned, namely myself, confused us totally. Because we heard the report from Smith explaining why it was so much easier at Smith College to put in a significant number of new students. They've even had some estimates that if they admit enough male students they would (at least as far as academic expenses go) make a profit. And since Smith College's endowment is nowhere nearly as good as Dartmouth's, and they certainly have much less graduate education than we do at Dartmouth, I at least am now totally confused on this score.

The committee realized early that, in order to make our report meaningful, someone had to come to grips with the very difficult detail issues of forecasting the effects of coeducation, forecasting the cost of coeducation, considering various alternatives of coeducation, and so on and so on. Therefore we followed the usual academic procedure, namely we set up a number of committees, which are beautifully charted on the chart that was given to you. So I would now like to turn to what the various groups have been doing, groups that are doing some of the hardest work in the entire study. We have decided that we must go through the exercise of asking some key questions on an if-then basis. Suppose Dartmouth went coeducational. How would we do it? What would the effect be? What would the cost be? Even if the decision after all this work turned out to be negative, we could at least say to the entire community that it was a decision we arrived at rationally, not a decision that was a guess or hastily arrived at.

The first of these committees (I mention it as first only in the sense that this committee's information has an effect on the work of all the others) was to concern itself with what we've called various alternative "models" of coeducation. This work required a great deal of quantitative study and we were fortunate in having Kiewit Computation Center available. Rather than try to duplicate dozens of computer out-puts, we have abstracted just two tables that you might find interesting. They might show you the kind of questions we are asking.

The first table shows three possible models of coeducation. The column marked "now" reproduces what has been standard at Dartmouth College for the last few years. We have 3,150 men and no women. We must also take into account that increasingly students like to spend a term away from campus; for example, in the foreign study program or in government internship. This somewhat reduces the load of the faculty so that the net total on campus is typically around 3,000 students. So this is our starting point.

THREE MODELSNow I II III Men 3150 3150 3000 2800 Women 0 1050 800 700 Ratio — 3:1 3.7:1 4:1 Away 5% 5% 10% 15% Net Total 3000 4000 3420 2975 Increase 33% 14% —1%

The committee after looking at dozens of models decided to identify two extremes: one which we call the maximum model and one which we call the minimum model. Frankly, one is the most expensive we dare to consider and one is the cheapest reasonable solution. These are labeled Roman I and Roman III.

Let's look at Roman numeral I first of all. That column might be described as the Princeton solution to the problem of coeducation. What Princeton University decided, with an undergraduate body almost exactly the same size as ours, was that they could not possibly reduce the number of male students, and that in order to achieve significant coeducation they would need a three-to-one ratio of men to women. Therefore, in our terms, we would need 1,050 women. If we assumed that the percentage of students off campus stays the same as before, this would mean that the students on campus would go up from about 3,000 to about 4,000 which is of course a ⅓ increase, and which is a very very sizable increase in the total enrollment. As you will see in a moment, there are very significant cost factors associated with it and therefore we said we can't possibly consider any model more expensive than that one.

We then went to the opposite extreme and this is Roman numeral III. We considered a modest reduction in the number of male students, say to 2800, a more extreme ratio of men to women, four to one, and therefore we would only need to admit 700 women. We also played around with various schemes by which we could encourage our students either to spend more time off campus or to make more use of the summer term, and the most optimistic figure we could come up with is that during the academic year as much as 15% of the students might be away in any one term. If all of these "ifs" were realized, we would have a net total actually slightly smaller than our present total and therefore, not surprisingly, the net cost of such a solution would be quite minimal.

There are, of course, major catches to that solution which I probably don't have to point out to you. For example, the 15% figure is hardly achievable here, but we put this down as the other extreme and I'm quite sure that if any solution is seriously considered, it will fall somewhere between Roman numeral I and Roman numeral III. Roman numeral II is shown as a model not as extreme as the others; it is sort of halfway in between. We picked 3,000 men, which was actually the last recommendation of the faculty of Dartmouth College as to what the size of the College should be. For various complicated reasons we have snuck up above that number. We have settled for a ratio of men to women somewhere between three to one and four to one for this model, so we have 800 women. We are taking into consideration the fact that students off campus are likely to increase, particularly when the threat of being drafted will disappear. Therefore, perhaps a 10% figure might be realistic there, giving us a net total on campus of 3,420 or about a 14% increase in enrollment on the campus.

Now these models are the starting points. From this somehow one has to come up with estimates as to what this means in terms of new faculty members, new academic facilities, dormitories, dining halls, and what the overall effect of such a change would be on the quality of education at Dartmouth College. We therefore turn to the second chart.

% INCREASE IN ENROLLMENTArea I II III Arts 106 67 43 Economics 29 12 —2 Engineering 4 —7 —18 English 45 23 7 Govt-Socy 32 14 —1 History 44 23 7 Languages 30 12 —2 Life Sciences 40 20 4 Math 18 4 —9 Phil-Religion 56 32 14 Phys Science 22 7 —7

In addition to the fact that we would increase the student body, we have to take into account the fact that typically women select their courses along a somewhat different pattern from the way men select their courses. This is the reason why, although in model number I you find that the total enrollment goes up by 33%, the enrollments vary enormously by subject matter. Under "areas" we have grouped departments of similar interests; for example, in the "arts" we have art, music and drama, and you will see under any of the models it is this area that has the heaviest increase, because it's an area that is particularly popular with women students. And not too surprising it's engineering that profits least from admitting women to college. If you look down column Roman numeral I you will find that most areas go up by a rather frightening margin and this has a very unpleasant implication. The way I like to describe this is to say that every academic building must have a new wing built on it. You know, faculties have very strong prejudices. They like to have their own facilities, they like to be near their colleagues. They certainly would not be happy if we said, Well, we have ⅓ more students, we'll build three more academic buildings out on the golf course, and have % of the English Department in Sanborn House and the other ⅓ elsewhere, and they can come visit each other once every other week. So this is a particularly unpleasant model because there is a huge increase across the board, which probably makes it about as expensive a solution as possible. I would not be surprised if the total increase in cost for that model would be more than one-third, because there are so many different facilities that would have to be altered.

If we turn to the other extreme, which is Roman numeral III, we find that, of course, the total enrollment stays about the same; therefore some departments go up and some departments go down. You may say on the average you break even, but unfortunately averages are not the key factors here. In spite of the fact that you break even on the average you will find that the arts go up by 43%. And there's a serious question of what the effect of that will be on Hopkins Center. You will also find that there are a number of departments, quite large departments, whose enrollments go down significantly. And, as you may know, one of the most difficult things in any academic institution is to reduce the size of a department.

Therefore, something like model II at least has better features, although it looks far from ideal to me. That is, except for engineering, which has graduate programs which could absorb losses in undergraduate programs (all these figures are purely for undergraduate enrollments), all the others go up. Many of them go up by very moderate margins and therefore it looks as if there might be a model if we were only clever enough and could guess well enough, under which one could get away with adding relatively few new academic buildings and relatively modest increases in the faculty. But we have certainly not so far been ingenious enough to come up with that magic combination.

Now this is simply a starting point. Given these difficult facts, we must somehow put a dollars and cents price tag on each of these models and, much more difficult than that, we must put an educational impact price tag on these. What would life be like on the Dartmouth campus under each of these models? One of the key considerations here is what happens to living conditions. And here is where the second working group, under the chairmanship of Professor Vargish, comes in. They are asking perhaps the most difficult questions of any of the working groups.

They were charged to work out for each of these models a recommendation in the way of living quarters on the Dartmouth campus. But they have taken that charge and have broadened it considerably to an overall survey of what the style of life, outside the classroom, is like on the Dartmouth campus today. They have looked at dormitories, dining halls, and social facilities and they have asked a number of very difficult questions: (1) What conditions in terms of living facilities encourage the educational process? (2) How could these be improved to provide better education for our students? (3) What effect on all of this would the admission of women have? And (4), perhaps the easiest of the four questions, What special needs, if any, do women have in terms of residences and dining? The example that is always brought up is full- length mirrors.

You will notice that the first two of these questions are quite fundamental questions for Dartmouth College even if the decision should be not to go coeducational. And they have looked at their task as one that's very important for us whether or not the decision is pro coeducation. They have surveyed the campus and they have found out that the living facilities on the Dartmouth campus today are quite Spartan. This we have been told was a policy decision of the institution during a period of rapidly increasing financial demands. The policy decision was made that the first priority should be the quality of the faculty and financial aid, and therefore dormitories and dining facilities have been kept self-financing, which necessarily has meant that they have been minimal in nature. This has led to some of the greatest complaints on the campus and raises one of these very difficult questions of principle as to how much you are willing to sacrifice in one area to make the living conditions more conducive to education. They have been learning a great deal about the financial facts of building new facilities, which I'm sure many of you know are quite dismal, and they have made very heavy use of student members both on the committee and outside the committee to set up task forces to try to find out what it is that really matters to students today, what the complaints are about and what students would really like to see.

They are trying a number of approaches, one of which I should certainly mention, because I think it is one of the most ingenious ideas I've heard. They have set up a committee they call the Utopian Committee. Because they have found that if you ask either students or administrators what a dormitory should be like, you get very unimaginative and unenlightening answers. Professor Vargish has said it's the same three suggestions that come up over and over again. And you have a terrible feeling that everybody is quoting the last person who made the three points. So they have set up a student committee with the task of designing an ideal dormitory. Not that anyone is going to build it for you, but they hope that in the process of going through this exercise the students will really show what those features are that are most meaningful to today's generation of students.

I can say that this is one working group that has already reached a conclusion. They have reached the conclusion that whether or not we go coeducational, it should be a high priority item to Dartmouth College to improve the living conditions for the male students here. Given the life style of students today, our living facilities are not acceptable, and they are a very serious handicap to the educational process.

The third working group, one that has gotten going only recently, is an all-student committee under the chairmanship of Sandy Ferguson. They call themselves the "Everything Else Committee," and they are looking into such questions as athletics, cultural activities, extracurricular activities and social life, most notably fraternities. In each case they are asking three questions: What is it like now; what is the future, let's say of athletics at Dartmouth College, if we stay all male; and what would the effect of the admission of women be in each of these areas? As I have said, they have just gotten started on this and therefore I can't give you any details, but it certainly is a committee which is very important to the overall work of the Trustees Study Committee.

And finally, the fourth committee has just been organized under the chairmanship of Mrs. Prosser, a member of the Dartmouth faculty. This committee is going to look into some special questions about the education of women. The main question they have asked themselves is the following: What are the educational goals of women students today? And closely related to this is the question: Is there anything special that Dartmouth can do for the education of women? This is a recognition that women are different from men. It is a recognition that women face different problems than men. The typical career pattern of a man, especially in time of peace, is to go through many years of education, graduate study, perhaps an internship or an apprenticeship, and then he can look forward to 35 years of uninterrupted career. The typical pattern of a woman is to go through perhaps just as much education, start a career and then have it interrupted for 15 to 20 years, after which she may try either to pick up that career or find some other way of using the enormous amount of education she had acquired.

There's a second kind of way in which women are different that's relevant here. And this is something we are beginning to realize more and more: that getting suffrage did not give women equality in a number of significant areas, due to very great social pressure.

The question we are all struggling with is this: It's sometimes terribly easy for all of us who have spent out life trying to work for an all-male institution to think of our goals entirely in terms of what is good for the education of Dartmouth men. And certainly it is a key issue - we are not going to do something that is bad for the education of Dartmouth men. And yet, there is a strong feeling on the committee that to bring women here purely because it is good for the men here, is something that we cannot in good conscience do. Unless Dartmouth has a significant contribution to make to the education of women, we should just forget all about coeducation.

This brings me to the last problem on which we don't have a working committee and yet is a very puzzling and perhaps absolutely fundamental question. Leonard Rieser has asked what if Smith College were kind enough to move up to within walking distance of the Dartmouth campus? That's a good way of introducing a question. There are many patterns of coeducation going under various headings. One of the headings is coordinate education. That is, just because Dartmouth decided to go into the education of women, it does not necessarily mean that it has to be full coeducation.

There are a number of other alternatives. Just this week there is an interesting article in Newsweek about that school down in New Haven, saying that they have admitted over 500 women and that some of the women at Yale are rather blue. I apologize for that. Incidentally in reading the Princeton report, a number of us had the reaction that Princeton looked at its report entirely from the point of view of men and somehow assumed that if you just take a group of intelligent women and drop them into the middle of an all- male campus, with hundreds of years of tradition, with all kinds of habits and attitudes, with an educational system entirely geared to males and say "You're terribly lucky to be here, just go ahead and make the best of it" - that all problems would be solved. We saw no evidence at all that either of those two institutions gave serious consideration to these problems, and we at least have not taken it for granted that there aren't other solutions that may be better. There may be solutions where you would share facilities and faculty and perhaps have common dining (students always say that having meals together is one of the best ways of making friends), and yet you could set up a women's institution in Hanover which would have a considerable degree of independence and freedom to work out its own destiny, its own traditions, and its own way of making the most of the available facilities.

When we came to this point in our deliberations, there was one overwhelming argument against it, namely, that it is completely against the national trend. Every other institution that had a coordinate institution is going in the opposite direction. Of course, very often "coordinate" really meant a quite separate institution, without any real ties to the main institution, which we are not talking about here. But still, the trend seems to be in the opposite direction.

But here I would like to come back to the point I started with, that Dartmouth is a unique institution in size, composition, and its history. We do not know of any that is exactly like Dartmouth and we are not willing in any of these deliberations to say that somebody else has done so and so, therefore we must do the same. It may not be the first time in the last decade that Dartmouth has made a decision that went completely against a national trend and yet it turned out that Dartmouth was right and others were wrong. We will look at all possible solutions and we will not copy other people. We will not be pressured into a solution, but we will try to work out Dartmouth's own destiny.

Mr. Timbers

THOSE of you who know something about the judicial process I think will respect my observation that we keep our minds open and reserve decision until the record is complete. The record before this Committee is not complete at the moment, as these gentlemen have made clear. We've gone a good way on the issue of the desirability of some form of education of women at Dartmouth. But on the issue of feasibility, which really means the price tag, I think all members of the Committee would agree that we have not even begun to scratch that surface.

What can the alumni of this College be asked to do on this issue? I don't think it takes a genius to figure out that this is a critical issue in the life of Dartmouth College. It also is an explosive issue and, unless handled properly, it could be a devisive issue - particularly vis-a-vis the alumni who, after all, are the largest constituency with which we're concerned.

I would like to suggest, as President of the Alumni Council, that we try to afford to all alumni an opportunity to be heard on this issue and earnestly and systematically to solicit their views. Let me say first, after some discussion in this Committee, I think we probably have rejected the notion of any sort of a questionnaire to all alumni. The fallacy of this approach is, I think, obvious. Furthermore, I think that any request that alumni express themselves pro or con after a decision has been reached is unthinkable.

It must be made clear to all concerned just who is going to make the decision once the Committee report is in. The alumni are not going to decide whether there will be coeducation at Dartmouth, nor are the students, nor the faculty, nor the administration, nor any other constituency except the sole decision-making body of the institution, namely, the Trustees. And while a matter so fundamental may seem obvious, I think it is of the utmost importance that we not lose sight of where the decision ultimately rests.

On an issue of this sort which cuts to the core of this institution and of our national life, the alumni of Dartmouth College should be heard. My proposal is that once a tentative report by this Committee is in hand - and I underscore the tentative stage - we have a series of regional meetings of alumni throughout the country, organized comprehensively so every section of the country is covered, so every concerned alumnus can participate. One or more members of this Committee would be in attendance, hopefully with one or more members of the Alumni Council, to sit down and discuss, as Dartmouth men should, the gut issues presented for consideration. My guess is, if a procedure of that sort were followed, that whatever the ultimate recommendation of the Committee might be it would receive the backing of the alumni of Dartmouth College, provided they understand the complexity of the problem and the professional skill which has gone into the analysis of it.

Committee Chairman Dudley W. Orr '29

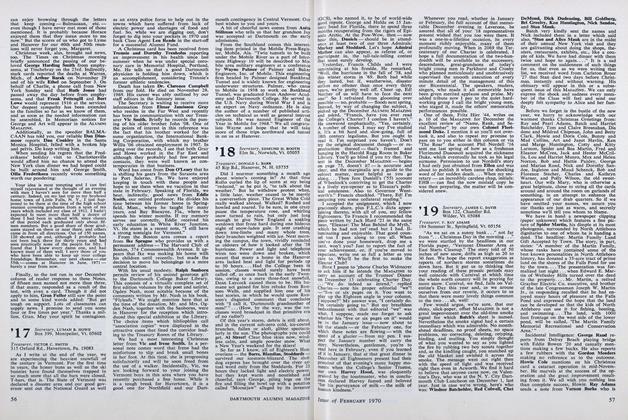

Professor Kemeny speaking at the joint Trustee-Alumni Council meeting. Seated(I to r) are Trustee Lloyd D. Brace '25, Council vice president Robert T. Mortimer '47, Trustee Dudley W. Orr '29, Dean Leonard M. Rieser '44, Mrs. ReeseProsser, Treasurer John F. Meek '33, and Prof. Thomas Vargish.

One of Dartmouth's current "exchange"coeds, Gabrielle Disario of Skidmore,shown in her dorm room at Cohen Hall.

Coeducational music in Hopkins Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom the Primate Patrimony To the Fellowship of Flowers

February 1970 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ, -

Feature

FeatureSpeaking of Books

February 1970 By FRANCIS BROWN '25, -

Feature

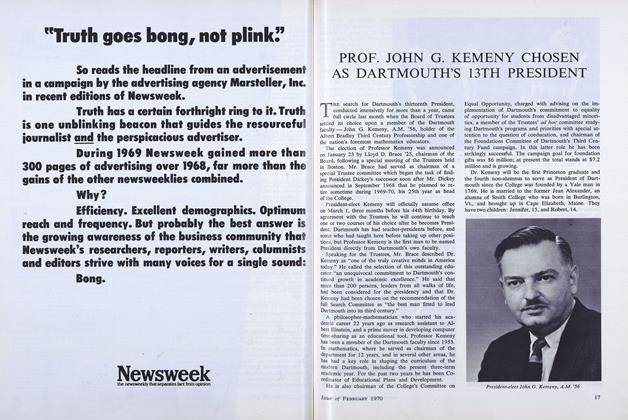

FeaturePROF. JOHN G. KEMENY CHOSEN AS DARTMOUTH'S 13TH PRESIDENT

February 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1970 By EDMUND H. BOOTH, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

February 1970 By JAMES C. DAVIS, F. RAY ADAMS

Features

-

Feature

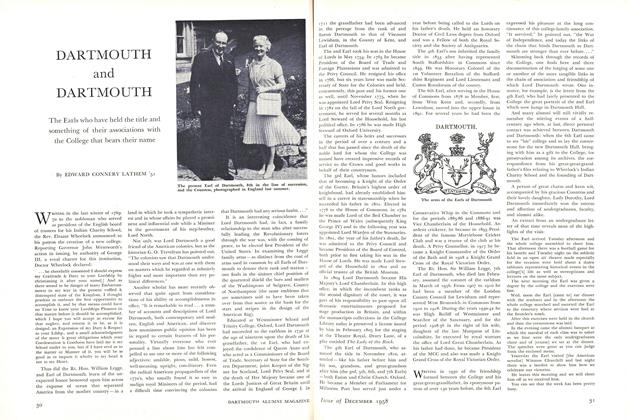

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

FEATURES

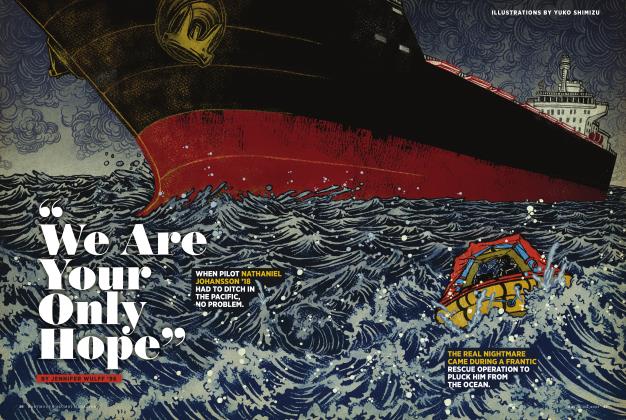

FEATURES“We Are Your Only Hope”

MAY | JUNE 2023 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

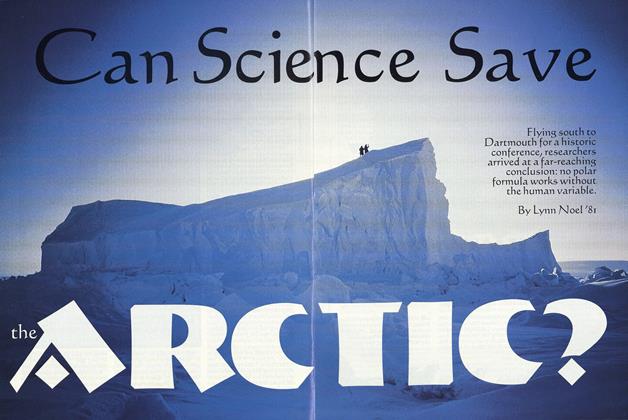

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

Feature

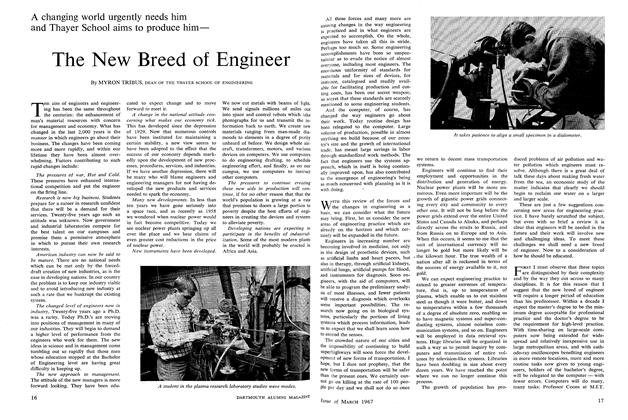

FeatureThe New Breed of Engineer

MARCH 1967 By MYRON TRIBUS -

Feature

FeatureSTRATS

APRIL 1986 By Willem Lange