EDITOR, THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

WHEN I was asked for a title that would describe what I was going to talk about, I really was put to it. Finally, "Speaking of Books" seemed best suited, and I chose it not in desperation, but deliberately. It is of course the title, the standing head as we call it, for one of our departments in The Times Book Review. In that department each contributor is given the privilege of selecting his own topic and his own approach, with the only test that what he writes have some pertinence to a publication like ours. He is, in other words, a free-wheeler, and since I want to do some free-wheeling myself this evening, I think that I, too, can be classified as a speaker of books. I am going to range rather widely and I trust that what I say will have some pertinence for our common interests.

First of all, some thoughts about libraries, A library, of course, is many things, and what we are thinking of tonight, I am sure, is the broad-gauge, working library that is part of an institution or is basic to a community. In Ireland a few years ago I had occasion to visit a quite different kind.

At historic Cashel, the seat of the ancient kings of Munster, the town whose ruins on a great rock are regularly featured in Irish travel literature, a library was being dedicated, perhaps re-dedicated is a better word. In the beginning, the books had been brought together by a bishop of the Church of Ireland in the early 18th century. He must have been a man of intelligence and taste, but whatever he was, he assembled a noble collection: among its items as I recall were an early Chaucer, Spenser's FaerieQueene, some volumes by Sir Philip Sidney, and there were many others, representing most notably the 16th and 17th centuries in authorship and book-making. Some of the books had belonged to Francis Bacon and his autograph was on their flyleaves. Over the years the bishop's library had been neglected, its books had deteriorated, were threatened with total decay. Then a new dean came to the cathedral church of St. John the Baptist in Cashel. He was a bookman. He took matters in hand.

To raise funds for restoration of the books, and to provide suitable quarters for them, took a lot of doing. One source of funds was the Folger Library in Washington, which bought duplicates in the collection and probably some others. In any event, the money was found. The upper floor of the chapter house in the yard of St. John's was renovated for library purposes, and handsomely. The old books were restored. So there it is, a small treasure house for bibliophiles, tucked away in rural Ireland. It's a treasure house, but not a working library for the likes of most of us.

Unless we are collectors of one sort or another, I wonder if what we want even of our personal collection is not a working library. We may cherish a few rare volumes, a few more of questionable literary importance that have sentimental significance, but if we are serious about the books we put on our shelves, then the ones we put there, the ones we keep there, are books that have some particular value, or some potential value, for our own needs.

A good many summers ago I rented with some young bachelor companions a house here in Hanover. One of the more mature among them expressed his scorn for the books in the house. What a miscellaneous collection, he said, what a useless and senseless assemblage, and then he added that he supposed it was like the personal library of most people. I made up my mind then that if ever I had a library of my own, it would not be senseless and it would be useful. At least it has been useful, and it represents my tastes and interests.

From the time I was a small boy I have been interested in history. I recall the first book of history that I read: a school text that had been my father's, Scudders History of the United States. At least I think that was the title, and I believe that this book with its faded yellow binding is still somewhere on our shelves in the country. Time went by, and soon, as an adult, I was buying history and biography, ranging first both American and European history, and then more especially American. Interest and enthusiasm have shifted from time to time, with emphasis on first one period, one area, then others.

In graduate school it was the American colonial period that was uppermost, and it was then that I made my one and only excursion into rare books. At the Anderson Galleries, which have now become Parke-Bernet, a sale was advertised of old American books. One of my fellow students at Columbia — it was Lawrance Thompson, the future biographer of Robert Frost - persuaded me that I should attend. Now in the catalogue was a first edition of Governor Thomas Hutchinson's History of Massachusetts Bay. At the time I almost felt that I knew the Royal Governor because he was very much a part of the doctoral dissertation that I was writing. So I went to the sale. Sure enough, the history came up, two volumes very beautifully bound in green morocco, a binding that must have been relatively modern.

The bidding began. I was an impecunious student who had no business being at the sale in the first place, but there I was and I bid. Suddenly I panicked. I was still in the bidding and the price had gone to fifty dollars, far above what I could afford and far more than I had in my pocket or was likely to have. Then some guardian angel took over. I was outbid. Yet, I couldn't go home empty-handed. A third edition, 1795, of Hutchinson came up, and I bought it for something like ten or twelve dollars. Whether it was worth the money, I still have no idea, but I have kept the volumes for forty years. They represent my rare book collection.

My library is not wholly devoted to history and biography, and you wouldn't expect it to be, though both are well represented, and some of the volumes have been well worn with use. Over the years first one book of reference and then another has been added. Works of literature, works on art, economics, sociology, current affairs are on the shelves. As my children came along, I tried to have books that would be of use to them. They did use them and in the process became book lovers. Now it is my grandchildren's turn and the promise is good.

For a generation my work has been such that books were available to me on a complimentary basis so that my actual purchases have been relatively small. Only when a special project was under way have I been a real book-buyer. When, for example, I was writing the life of Henry J. Raymond, a founder of The Times, I searched the second-hand book stores for books that would supply the facts and figures and the feel of New York and its newspapers in the mid-nineteenth century. Sometimes the titles were delightful: for instance, Sunshineand Shadow in New. York, 1868, inscribed "Frederick W. Francis from Mother." I wonder who he was and if he ever read his mother's gift.

When I left Time Magazine after some years as a senior editor, a friend of mine was asked what he thought I would like most as a parting gift. He knew me well, and he replied the Dictionary of American Biography. And so at the height of a very gay farewell dinner at "21" I was the surprised recipient of the twenty volumes of the DAB. I left "21" at about three in the morning, in a thick alcoholic haze. With me I carried the twenty volumes, feeling for all the world like a drunk who had brought home a hydrant. But it was a wonderful present.

As editor of The Times Book Review I have been in an enviable position so far as building a library is concerned. And at times my family must have wished my lines had been cast in other waters. There have been almost too many books, but I wouldn't have had it otherwise.

I'm afraid I haven't been like the Irish professor about whom I was told recently. The professor, a distinguished economist at the National University in Dublin and a member of the Irish Senate, had a home that was noticeably bare of books. When asked why it was that he, a scholar for whom books were tools, had none at home, he replied, "Does a butcher keep sides of beef in his house?"

Editing a Book Review like ours, despite its many headaches, has been a constantiy stimulating and satisfying experience. A book review, and I'm speaking now of the individual book review, can be an adventure for its writer, its reader and its editor. Let me talk about book reviewing for a few minutes.

What is a book review anyway, what is its reason for being? Book reviews are, in a sense, only good, informed talk (written, that is) about books. Usually this written talk is of new or current books. It could just as well be about old ones, only then what is really a review balls itself a literary essay.

Now there are, there have been, and there will be tomorrow, all kinds of book reviews, which is another way of stating that there is no set formula,, that there are no set rules. In the early 19th century Lord Macaulay (he was plain Thomas Babington Macaulay then) made himself famous in the Edinburgh Review by writing what began as a book review and became an essay on the subject presented by the book, the book itself meanwhile being lost and forgotton in the rolling periods of Macaulay's prose. Lesser Macaulays are still writing that sort of essay, and it can be excellent reading for what it says and as a literary exercise, but it is not very satisfactory for anyone concerned with the book that started it all.

At the opposite pole, or at least far removed is the routine review that has nothing to recommend it. The time is long gone, if it ever was, when a book review reported only a book's title, authorship and content - much like those school reports of blessed memory - but even now too many reviews are being written that are first cousins of such a bare bones performance. The reviewer, maybe taught in school that this is the way to do it, tells what a book is about, makes a point or two of minor criticism, concludes with a general endorsement that is meaningless, and then picks up his marbles and goes home. Such reviews are not to be taken seriously.

What do matter are those first-rate, often brilliant reviews that are the products of a first-rate, often brilliant mind that has got inside the book under review, and in telling what has been found frequently sets in motion ideas and thoughts that are stimulating in themselves, over and above what the author has done. The result, and some of what I am saying I have said on other occasions, may be also a well-turned piece of literary criticism. In England a generation or so ago Virginia Woolf's book reviews were an instance, and while there are not many Virginia Woolfs, and as a critic she has less to say to us now than to her own time, her kind of book review has set a pattern that many have followed to the reader's great profit and delight. These are the reviews that make bright a literary editor's day.

A first-rate reviewer, whether a Virginia Woolf or not, has to have something to say and be willing to say it, and it would be well if he did not follow the precept of the English wit, Sidney Smith, who said "I never read a book before reviewing it; it prejudices a man so." Sometimes, to be sure, it does seem that reviewers have the precept in mind - I've seen some exhibits - but, to repeat, I don't recommend it. However unconventional a reviewer's approach to his material, somewhere in the review he is writing, and this would seem to be fundamental, he must reveal what the book is about and what is its nature. He has to do more, and he does.

Because the purpose of the best book review is to furnish perspective, to put in place, to further appreciation, sometimes to challenge the accepted, the reviewer must ask himself a lot of questions. He must, for example, ask what does the book's author bring to it as a writer and a thinker? What is he trying to do? How has he gone about realizing his aim, where has he failed and why, where been successful? What contribution to knowledge, to comprehension, of man and his world has he made, where does this fit into his own previous work as an author, into that of others who have been gleaning the same field?

Such questions are easier to ask than to answer, for their answering, and the nature of the answers, calls not only upon a reviewer's own knowledge and philosophy, but upon his appreciation of the task of literary creation. Moreover, questions that are pertinent to one book and author may be quite out of turn with others. Obviously one does not judge Norman Mailer and Frances Parkinson Keyes by the same standards.

The best critics not only have something to say, they know how to say it and want to say it. But in the saying there are many accents and intonations.

Americans by tradition, or so we are assured, are a kindly people, and while this quality has not prevented assault upon a man's politics or his ancestry, it has often protected him in the practice of authorship. The frequent result has been a hesitancy, almost a congenital unwillingness, to disagree with the thesis of a book and its development, or to speak out and pronounce the verdict: bad, bad, bad. There has been dislike, perhaps it is fear, of controversy.

By contrast there are critics who are not afraid to hear their own voices, to speak their minds. The number, thankfully, seems to be increasing, and why not? A well-informed reviewer should not be afraid to praise when praise is due or to attack, maybe demolish, when the nature of a book so determines. It is the vigorous independence, the candor, with which a man sets forth his position that gives strength and ultimate conviction to his criticism. When he hedges, he is unfair to himself, to the reader, and eventually to the author, for from criticism the knowing author can learn much.

The ideal is always easier to describe than to attain. The root of the problem, from beginning to end, lies obviously in the critic, the reviewer, and there have never been enough good ones.

To preserve the independence that should be a sine qua non of the profession, criticism must be as free from logrolling and knifing as it is from the control of clique or claque. Yet one of the hardest things about assigning books for review, as every literary editor has learned, and I had to learn it too, is to keep friends from friends, enemies from foes. Perhaps there are times when exceptions can or should be made, but only when one can be certain that friendship will not count and enmity will be temporarily adjourned. To repeat, the best reviewing is that which is farthest from deliberate log-rolling or premeditated knifing.

At the risk of sounding like a bloody colonial speaking ill of his betters, let me say that the English reviewers are notorious for not abiding by this rule. Behind the anonymity of the T.L.S., for example, they often promote their friends and savage their enemies, and sometimes without the cloak they do so in the full daylight. We at The Times have been unwitting victims of this custom on occasion.

I recall one instance. C.P. Snow, with whom I have a degree of friendship, once asked me if he could review a novel by William Cooper. My guard should have been up - but it was down. He reviewed the book for us, favorably, and only afterward did I learn that not only was Cooper a" friend of Snow's, but also a sort of protege. That, as the English say, was naughty.

A somewhat different case, but it makes the point, involved a distinguished British historian who had written a chapter of autobiography. I ran into him, told him that we were reviewing his book. He asked the name of the reviewer, and I told him. "Oh," said the historian, "how could he? Why, I don't even know the man."

A good, well-rounded book review can be a wonderfully exciting thing for it offers the excitement of discovery. The reviewer is setting forth what he has found in a book, and if the book is a good one, and sometimes even if it is a poor one, he has found a lot, whether it is new understanding of the human animal or fresh interpretation of his origins or new insight into what made John Keats tick. He shares his discoveries with the reader, just as he may take the reader on philosophical excursions or artistic digressions that the book at hand suggests. Readers may be outraged (and often are) by what the reviewer has said and the manner of his saying it, but is that bad? Dissent in itself can be exciting, can bring light into gray corners. As our culture becomes more and more unified, diversity is a quality to be cherished and cultivated, and how dull it would be, how stultifying, to find ourselves in agreement on politics, aesthetics or what you will - and most of all on books which by their very being testify to man's diversity and the importance thereof.

These general observations constitute the ideal, and the ideal, alas, is too seldom realized. An editor and his staff may have the best of intentions, may have the ability, the knowledge, yes even the intelligence to bring off this ideal, and yet find themselves confronted by what Grover Cleveland in a different context described as a situation not a theory.

How is the ideal to be attained, for instance, when a book review like that of The New York Times, is faced with 8,000, 9,000 books or more a year, and can at best review perhaps only 2,500 of them? Obviously some good books are passed over, some poor ones are reviewed unnecessarily, some books are assigned to the wrong reviewers.

What is an editor to do about reviewers who stubbornly refuse to meet deadlines, disregard the length assigned for their reviews, kick like steers if their copy is altered, however much alteration may be in order, who in short act like prima donnas?

How does an editor resist, and he must resist, the pressure of authors, not to mention their friends, and of publishers and their friends?

How does he settle the question of judgment and taste raised not only by readers but by his own staff?

I sometimes marvel that we do as well as we do, and actually, if you press me, I'll tell you that, with occasional lapses, I think our job is well done.

But the issues that I have raised are somewhat common to all reviewing media. At The Times, and I suppose this must be true to some extent of other newspapers with book review sections, we are constantly aware that we are part of a newspaper, and in our case a newspaper that boasts of its broad coverage. What exactly does this mean?

It means that first of all we are reporting, analyzing, putting in perspective the news in books, whatever their nature. It means also that we are more concerned than would be a strictly literary magazine with books dealing with current affairs, whether politics in the narrow sense or in the large. Moreover, because of the Times principle of broad coverage, we feel obliged to cover, and we believe that this is right, very right, the many varieties of books that come from American presses. Not all: some are too specialized, some are unworthy. But we are speaking to an audience that is presumably as varied in its tastes and interests as the books we are reviewing. This is not a limited audience of special interests. The Sunday Times has a circulation of more than 1,500,000. We have to speak to that audience in many ways. We seek to guide it to the best and most significant, and we like to think that often we have planted some important ideas in the minds of our readers.

Mr. Brown speaking at NECL banquet.

Francis Brown's talk, "Speaking of Books," was given in Hanover on April 25, 1969, at the banquet of the annual meeting of New England College Librarians. The program for the meeting, the largest NECL gathering ever held, was arranged by the Dartmouth Libraries under the sponsorship of the Kenneth F. Montgomery Foundation. Mr. Brown, holder of Dartmouth's honorary Doctorate of Letters (1952), has been editor of The New YorkTimes Book Review since 1949. He is the author of four books and has edited or contributed to a number of other volumes. He is the editor of the Bicentennial book, A DartmouthReader, that was published on Charter Day, December 13, 1969. He was a member of the Dartmouth Alumni Council from 1951 to 1957 and served as vice president of the General Alumni Association in 1958-59.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom the Primate Patrimony To the Fellowship of Flowers

February 1970 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ, -

Feature

FeatureThe Pros and Cons of Coeducation

February 1970 -

Feature

FeaturePROF. JOHN G. KEMENY CHOSEN AS DARTMOUTH'S 13TH PRESIDENT

February 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1970 By EDMUND H. BOOTH, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

February 1970 By JAMES C. DAVIS, F. RAY ADAMS

FRANCIS BROWN '25,

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Student View of the Crisis, 1816-19

FEBRUARY 1969 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThao Dinh Vo '91

March 1993 -

FEATURES

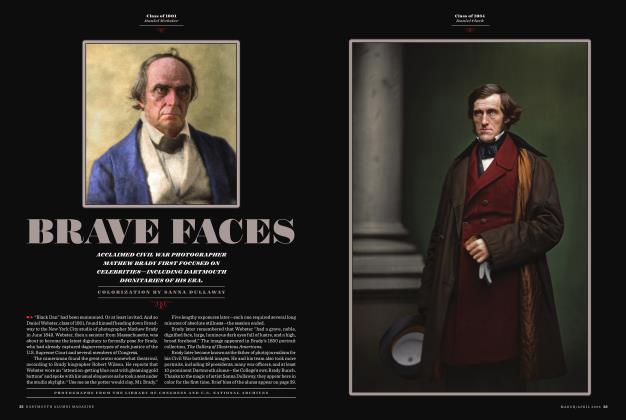

FEATURESBrave Faces

APRIL 2025 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

OCTOBER 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Teri Allbright -

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

DECEMBER 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40