THE use of size as a criterion of greatness is an American failing. This is probably, at least in part, a heritage from the nineteenth century. When the West was being opened up, we heard a great deal about the height of Niagara Falls and its mighty volume of waters, about the depth of the Grand Canyon, the length of the Mississippi River (even the Indians got the idea and called it The Father of Waters), about the broad range of the prairies, about the huge extent of the untamed wilderness.

We liked to conjure with notions of national greatness. We spoke with pride of the Great Lakes, the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, the Great Divide of the Rocky Mountains - as if there were no great lakes or deep valleys or tall mountains anywhere else on the face of the planet.

Our political orators - many of whom employed what my friend Julian Boyd calls "the old wet-mouth style of delivery" ran the gamut of the available adjectives: vast, far-flung, immense, enormous, measureless, unbounded, huge, gigantic, limitless, stupendous - and of course colossal. We turned to Greek mythology for the adjective Titanic, to Homer for the term Cyclopean, to Rabelais for Gargantuan, to Swift for Brob-dingnagian. There was a kind of jingoism in our constant stress on the size of our population, the wealth of our natural resources, the growth of our cities, the vast network of our roads and railroads, the amassment of personal fortunes. We did not invent the term millionaire the French did - but we forcibly adopted it because it fitted very well into the kind of thinking we were accustomed to.

This habit of mind carried over into the present century. In 1881, Phineas T. Barnum merged with James Bailey to form a circus known as "The Greatest Show on Earth." When Bailey died and Barnum and Bailey combined with Ringling Brothers' Circus in 1906 or there-abouts, there was no place for the Greatest Show on Earth to go but Out of This World - a concept which the press agents are still using. But when anything in America goes out of this world - as for example the vehicle of the astronauts it bears the stamp of "Made in America." Phineas T. Barnum would doubtless be flattered to know that the biggest box of soap powder in the A & P is sized as Jumbo, after the largest elephant in his circus.

But Jumboism in education is not necessarily a criterion of greatness. On the contrary, the times at Dartmouth when we felt ourselves being actively educated - that is, literally drawn out of ourselves towards new goals and new concepts were those times when we communicated directly with one another, or three or four others, and hardly ever with hundreds or thousands of others. There is, we say, strength in numbers. But this is not necessarily so in education, where we need above all the personal give-and-take, the direct communication of man to man, the discoveries that men can make in pairs or small groups.

The Word of the Lord in Genesis increase and multiply —is surely being followed in our day with ever-increasing acceleration. To meet the problem of over-population we are trying to devise various methods of control - and having a hard time of it for reasons that I will not explore. To meet the problem of over-population in education, we have devised huge universities as complex as cities, and sometimes nearly as inefficient. They need their own police forces, fire departments, parking plazas, highrise hotel dormitories, and cafeterias to feed the multitudes off paper plates and with plastic utensils. The lecturer is often a distant figure on the podium, nearly as inaccessible as a star. The classroom teacher is often a graduate student who will rush away from the class hour to grade undergraduate papers and then, in the small hours, try to get on with his doctoral dissertation. What we call education is sometimes a travesty of education. We have to do it, but in our burgeoning society we need the available antidote of the relatively small liberal arts college where the-best in education can be offered to smaller numbers. Dartmouth is such an antidote to hugeness.

Our job in all this welter is to provide for the nation an aristocracy of brains and talents to lead us through the limitless challenges of the next hundred years. Such an aristocracy will emerge - I have Jefferson's faith that education is one of the best ways to guarantee its emergence. It will come by a process of trial and error both from the multiversities and the small private colleges. Genius will not be put down. But the chances for the nurture of genius are far better in colleges like Dartmouth than they are in larger places. For among the criteria of greatness is one of quality that has nothing to do with size. Dartmouth enters — on this very night - her Third Century. This criterion of quality is paramount in the thinking of her teachers and her administrators. The antidote for greatness in the sense of size is greatness in the sense of quality.

We are met here tonight to celebrate a truly historic occasion. And we all need a sense of history. In our diurnal preoccupations we are too often endstopped. If we cannot see around the corner of time into the future, we can at least look into the past. The Brooklyn schoolboy studying Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter was at least trying to look into the past when be wrote that Hawthorne's heroine, Hester Prynne, was "caught in a society which opposed the ideals of adultery very strongly." If you will forgive a personal reminiscence, I can provide yet another illustration of the force of the historical sense. Some years ago a New jersey state senator was introducing a bill for improved narcotics control. He asked me to go over the bill with him and help straighten out the language. Part way through this task, which took all day, I came on the term "snowbound." I had been raised in New England and Snowbound meant to me a famous poem by John Greenleaf Whittier. But here was the same term in a new context. I asked what it meant. Well, said the senator, one of the slang terms for heroin is snow. If you are an addict, you are said to be snowbound. It was an arresting transfer of terminology. It showed how far down the trail our civilization had slid from the clean, cool, joyful, agrarian experience of being snowbound on a New England farm in midwinter, with a long tradition of family solidarity at the core of daily life and then that other meaning of snowbound, growing out of the awful experiences of drug addiction in the ghettos of a corrupt city during a long hot summer.

Colleges like Dartmouth can not only provide their students with a needful sense of history, but they can also provide us with all sorts of corrections to the errors we entertain whether as individuals or as groups. They open up long vistas down the corridors of human experience. They provide us with legitimate means to legitimate ends, and it would not be too far-fetched to inscribe over the doorways of every classroom and library entrance in Hanover in letters of gold: The Dartmouth College Power and Light Company.

I should like to pay heartfelt personal tribute to the members of the Dartmouth Board of Trustees, both past and present, and to the two most recent Chairmen of the Board of the Dartmouth College Power and Light Company - the late Ernest Martin Hopkins, who was the great man in charge when I was there, and John Sloan Dickey, our excellent outgoing president, whom I have come to know and greatly revere during the years of his administration. They used their power to dispense light, and we are the people who benefited from their actions, as our sons have done, and as their sons will do throughout the rising generations.

Both Hopkins and Dickey have been great believers in right action. They share with Ralph Waldo Emerson a belief that without action the student, the scholar, is not yet man. Without action, "thought can never ripen into truth." It is Emerson, speaking of education, who quotes the Arabian proverb, "A fig tree, looking on a fig tree, becometh fruitful." Any college like Dartmouth is like an entire wide orchard of fig-trees. One of the ways in which our minds can be stirred to the roots and then rendered genuinely fruitful is to turn and return often to these orchards of intellectual impregnation. Multum in parvo, they used to say: the macrocosm is implicit in the microcosm. Perhaps, if we think of Arabia once again, a college such as Dartmouth is like one of those cool groves of trees beside refreshing water in the midst of the sands of the desert. Dartmouth College, and others like it, is one of the few remaining oases of knowledge and wisdom in our neon wilderness, our air-conditioned nightmare where the air is evermore in more terrible condition, and where we are too hurried and harassed by the conflicting winds of circumstance to let thought ripen into those truths that we need to go on with.

Carlos H. Baker '32, who is WoodrowWilson Professor of Literature at Princeton University, gave this talk about theCollege at the dinner meeting of theDartmouth Club of Detroit on CharterDay, December 13, 1969.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Rise and Fall of Humanity

March 1970 By WILLIAM W. BALLARD '28, -

Feature

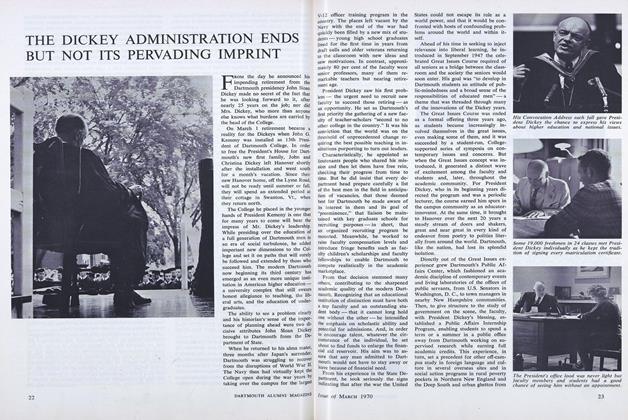

FeatureTHE DICKEY ADMINISTRATION ENDS BUT NOT ITS PERVADING IMPRINT

March 1970 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Priorities for 1970

March 1970 -

Article

ArticleThree Students Argue for Coeducation

March 1970 By CHERYL CAREY, Coed, RANDY PHERSON '71, RICHARD ZUCKERMAN '72 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '7O -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1970 By EDMUND H. BOOTH, DONALD L. BARR

Article

-

Article

ArticleGrades Improve

January 1939 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Holding Pace

MAY 1957 -

Article

ArticleRugby

April 1976 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS DENIES DISCRIMINATION AGAINST JEWS

June, 1926 By Ernest M. Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE OUTING CLUB REORGANIZES

November 1935 By Natt W. Emerson '00 -

Article

ArticleGI Planners and Program.

FEBRUARY 1966 By R.J.B.