FROM the day he announced his impending retirement from the Dartmouth presidency John Sloan Dickey made no secret of the fact that he was looking forward to it, after nearly 25 years on the job; nor did Mrs. Dickey, who more than anyone else knows what burdens are carried by the head of the College.

On March 1 retirement became a reality for the Dickeys when John G. Kemeny was installed as 13 th President of Dartmouth College. In order to free the President's House for Dartmouth's new first family, John and Christina Dickey left Hanover shortly after the installation and went south for a month's vacation. Since their new Hanover home, off the Lyme Road, will not be ready until summer or fall, they will spend an extended period at their cottage in Swanton, Vt., when they return north.

The College he placed in the younger hands of President Kemeny is one that for many years to come will bear the impress of Mr. Dickey's leadership. While presiding over the education of a full generation of Dartmouth men in an era of social turbulence, he added important new dimensions to the College and set it on paths that will surely be followed and extended by those who succeed him. The modern Dartmouth now beginning its third century has emerged as an even more unique institution in American higher education a university complex that still swears honest allegiance to teaching, the liberal arts, and the education of undergraduates.

The ability to see a problem clearly and his historian's "sense of the importance of planning ahead were two dicisive attributes John Sloan Dickey brought to Dartmouth from the Department of State.

When he returned to his alma mater, three months after Japan's surrender, Dartmouth was struggling to recover from the disruptions of World War II. The Navy then had virtually kept the College open during the war years by taking over the campus for the largest V-12 officer training program in the country. The places left vacant by the Navy with the end of the war had quickly been filled by a new mix of students young high school graduates freed for the first time in years from draft calls and older veterans returning to the classroom with new ideas and new motivations. In contrast, approximately 80 per cent of the faculty were senior professors, many of them remarkable teachers but nearing retirement age.

Presedent Dickey saw his first problem - the urgent need to recruit new an faculty to succed those retiring - as an opportunity. He set as Dartmouth's first priority the gathering of a new faculty of teacher-scholars "second to no other college in the country." It was his conviction that the world was on the threshold of unprecedented change requiring the best possible teaching in institutions purporting to turn out leaders.

Characteristically, he appointed as lieutenants people who shared his mission and then let them have free rein, checking their progress from time to time. But he did insist that every department head prepare carefully a list of the best men in the field in anticipation of vacancies, that those deemed best for Dartmouth be made aware of its interest in them and its goal of "preeminence," that liaison be maintained with key graduate schools for recruiting purposes — in short, that an organized recruiting program be mounted. Meanwhile, he worked to raise faculty compensation levels and introduce fringe benefits such as faculty children's scholarships and faculty fellowships to enable Dartmouth to compete realistically in the academic marketplace.

From that decision stemmed many others, contributing to the sharpened academic quality of the modern Dartmouth. Recognizing that an educational institution of distinction must have both a top faculty and an outstanding student body - that it cannot long hold one without the other — he intensified the emphasis on scholastic ability and potential for admissions. And, in order to encourage talent, whatever the circumstance of the individual, he set about to find funds to enlarge the financial aid reservoir. His aim was to assure that any man admitted to Dartmouth would not have to stay away or leave because of financial need.

From his experience in the State Department, he took seriously the signs indicating that after the war the United States could not escape its role as a world power, and that it would be confronted with hosts of confounding problems around the world and within itself.

Ahead of his time in seeking to inject relevance into liberal learning, he introduced in September 1947 the celebrated Great Issues Course required of all seniors as a bridge between the classroom and the society the seniors would soon enter. His goal was "to develop in Dartmouth students an attitude of public-mindedness and a broad sense of the responsibilities of educated men" - a theme that was threaded through many of the innovations of the Dickey years.

The Great Issues Course was ended as a formal offering three years ago, as students became increasingly involved themselves in the great issues, even making some of them, and it was succeeded by a student-run, conllege supported series of symposia on con-temporary issues and concerns. But when the Great Issues concept was introduced, it generated a distinct wave of excitement among the faculty and students and, later, throughout the academic community. For President Dickey, who in its beginning years directed the program and was a periodic lecturer, the course earned him spurs in the campus community as an educator-innovator. At the same time, it brought to Hanover over the next 20 years a steady stream of doers and shakers, great and near great in every kind of endeavor from poetry to politics literally from around the world. Dartmouth, like the nation, had lost its splendid isolation.

Directly out of the Great Issues experience? grew Dartmouth's Public Affairs Center, which fashioned an academic discipline of contemporary events and living laboratories of the offices of public servants, from U.S. Senators in Washington, D. C., to town managers in nearby New Hampshire communities. Then, to give structure to the study of government on the scene, the faculty, with President Dickey's blessing, established a Public Affairs Internship Program, enabling students to spend a term or a summer in a public office away from Dartmouth working on supervised research while earning full academic credits. This experience, in turn, set a precedent for other off-campus study in foreign language and culture in several overseas sites and in social action programs in rural poverty pockets in Northern New England and the Deep South and urban ghettos from Boston and Jersey City to Compton, California. Nearly 10 per cent of Dartmouth's undergraduates now participate in these programs each year.

THE planner in John Dickey recognized that he could not help Dartmouth realize the potential of the institutional strengths he inherited from his predecessor, Ernest Martin Hopkins, by a series of ad hoc innovations, no matter how wide and beneficial their ripple effects might be. He therefore persuaded the Trustees of Dartmouth College to set up a Trustees Planning Committee in 1954 to decide what the College should accomplish over the 15 years remaining before its Bicentennial.

Even then looking ahead to the anniversary, he said it was important that Dartmouth be able to say on its Bicentennial that it had produced an "undergraduate educational operation worthy of celebration as she moved from her second to her third century."

Rarely has a college so critically examined itself from stem to stern over so many years, or seen so much accomplished as the result of a searching survey of its strengths and shortcomings.

With the important support of the Trustees, and under President Dickey's alternate guidance and goading, Dartmouth re-instituted doctoral programs under its Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Significantly it has keyed them to serve Dartmouth's singular purposes and reinforce Dartmouth's strengths by keeping them relatively small, encouraging advanced scholarship without losing sight of the undergraduate student or the centrality of liberal learning.

As part of the mission President Dickey perceived for Dartmouth he also undertook the "refounding" of the Medical School, fourth oldest in the nation, recognizing that in the Medical School and the Mary Hitchcock Hospital associated with it, Dartmouth offered the major medical facility for the central section of northern New England. The Medical School under Dean Carleton Chapman is now moving to implement next fall a shortened and improved M.D. degree program designed to be a model for meeting the twin needs of the nation for more physicians and better medicine.

And still in the graduate area, President Dickey provided the essential encouragement to the faculties of the two other professional schools - the Thayer School of Engineering and the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration - that produced new approaches to teaching and learning, as well as their increasing coordination.

The birth of the Hopkins Center for the Creative and Performing Arts - a modern agora, or meeting place, for all the arts - is uniquely a product of the Dickey style of administration and one which has perhaps most profoundly influenced the general tone of life at Dartmouth.

For decades Dartmouth had been writing and rewriting plans for a theater-auditorium, a project given high priority by the Trustees Planning Committee. But none of the old plans satisfled President Dickey, nor did any of the modifications. Somehow, he felt a concept of commanding purpose was missing. Then, according to Richard Olmsted '32, now business manager of the College, Dr. Adelbert Ames of the Dartmouth Eye Institute ventured at one of the building committee meetings the notion of a forum for all the arts.

"You never saw anyone run so fast with an idea," Mr. Olmsted recalls. "That building seemed to grow right in front of our eyes as Mr. Dickey expanded on the concept, touching us all with the fire of his enthusiasm."

Once controversial in its modern design amid the traditional colonial and neo-Georgian, the $8-million barrelvaulted building, completed in 1962, added a crisp contemporary look to the campus. But more, it brought the arts, never previously strong at Dartmouth, into a central place in the life of both students and faculty and made Dartmouth the regional oasis for the arts in northern New England. It also gave Dartmouth a stage for internationally acclaimed Congregations of the Arts each summer, through which Dartmouth became one of the leading patrons of modern serious music.

Dartmouth's role in pioneering the educational uses of computer time-sharing, now being widely emulated, reflects another facet of President Dickey's leadership style. Among the new faculty recruited to take Dartmouth into its third century were two mathematicians: John Kemeny, destined to become the College's 13 th President, and Thomas Kurtz. While revising and invigorating the mathematics curriculum, they came to President Dickey with a then revolutionary plan for the computer as an educational tool. They rejected "batch processing" computer equipment then in general use in schools and colleges, because they argued, it placed computer experts and programmers between users and the tool. Rather, they reasoned that an educational institution should make it possible for students to learn about the computer by using it. They wanted to gamble on developing a time-sharing system that would let Dartmouth students learn about the computer by their own experimentation. President Dickey gave them the go-ahead on a combination of faith and fact-finding. They, in turn worked with General Electric engineers to give Dartmouth a tool that has had powerful impact not only on each school and department in Dartmouth, as more than 85 per cent of its students gain "hands-on" knowledge of the computer, but on education in general. Now, Dartmouth is exporting its experience to schools and colleges throughout the country. Tangible symbol of this advance, which recently brought a parliamentary team from Japan to study the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System, is the Kiewit Computation Center, completed three years ago.

FROM the Pennsylvania Dutch country of Lock Haven, where he was brought up, Mr. Dickey brought to Dartmouth as a student and later as President a strong sense of the importance of a moral purpose, and, he was not long into his presidency when he felt that students needed vehicles for their idealism and ethical concerns. He was also concerned that for men receiving liberal learning to be leaders of the nation it was increasingly important that conscience be wedded to competence.

To this end, he inspired the establishment of the Tucker Foundation, named after William Jewett Tucker, Dartmouth President at the turn of the century and last of its minister leaders of the past. Under the wing of the foundation, Dartmouth has developed a score of unique programs by which students may devote themselves for a term or two to working at the business of creating a better society and to helping individuals find themselves.

Out of this concern grew Dartmouth's pace-setting work in its ABC (A Better Chance) program to prepare educationally disadvantaged secondary-school students - blacks, Indians, Puerto Ricans, Mexican-Americans, and whites - for college and the opportunities they otherwise might not have.

Today Dartmouth students provide the sinews of that program as tutors here and 'at ABC homes in eight New England communities cooperating in the venture. Most of them are not aware that the program literally was hatched by President Dickey following discussion in 1964 with preparatory school headmasters over the need for "bridge" programs for disadvantaged youngsters at the secondary school level.

Similarly, it was President Dickey who early in 1968 sparked the formation by the Dartmouth Trustees of an Equal Opportunities Committee to study how Dartmouth could improve its contribution to realization of the nation's founding idealism.

And when Dartmouth negotiated with its black students a general Afro-American program, the President insisted that his staff examine the merits of the black "demands" and ignore their rhetoric. "No white man, no matter how hard he tries, can understand the burdens black Americans carry from 100 years of discrimination on top of 200 years of slavery," he reminded his staff in urging that equity has many sides.

Characteristically, President Dickey, who loves the outdoors and the natural environment of Dartmouth, kept in mind always the whole Dartmouth man, matching his concerns with curriculum and conscience with attention to the physical well-being of the students. Thus, the Dartmouth Outing Club - with its 50 miles of trails and many huts and cabins beckoning book-weary students - had a priority claim on his attention.

Only a President with a love of hiking and the out-of-doors would have made it possible for the DOC to organize each fall a week-long freshman trip which introduces 400 entering freshmen, or about half of each new class, to the hills and trails of New Hampshire even before they learn their way around campus. And every year, he made four trips during that week 50 miles north to Dartmouth's Moosilauke Ravine Lodge to greet each group of freshmen and share with them something of his philosophy about the College and life. As part of this concern for the whole man and the total institution, his administration added to Dartmouth's athletic facilities the Dartmouth Skiway 15 miles north in Lyme, the Leverone Field House, a new swimming pool and basketball court in the gymnasium, and artificial ice in the hockey rink. He also supported the evolution at Dartmouth of perhaps the largest ski school in the East as part of the physical education program.

Meanwhile, this concern with nature led inevitably to a concern with the quality of the environment. Again "seeing the problem," President Dickey sparked the recent moves of the College and its graduate schools to formulate a regional program, whereby its diverse resources -in engineering, business administration, medicine, the sciences, and the arts - could be brought to bear on the problems of change confronting northern New England as a model of university-community relations of substance and value to both.

President Dickey still found time among his chores on and off campus to walk his golden labrador retriever, his constant campus companion, down to the practice fields inconspicuously to watch the football team go through its drills or the track team work out. And when the seniors left a major team, each man received a personal hand-written note from the President, and each knew from what was in it that the President had composed each note himself.

Except when he was in conference, the door to his office was always open, and he saw more faculty, students and staff without appointment than with. Because he believed it important to make special efforts to share his thinking with the students, he never turned down an invitation to speak to a dormitory, fraternity or social group if it was humanly possible for him to acept.

This keen concern for the individual student, for the institution, and for both academic integrity and freedom led President Dickey to support the effort by students and faculty to articulate more than a year ago a Dartmouth policy on "Freedom of Expression and Dissent."

His concern for both the student and the institution also made the breach of that policy last spring by anti-ROTC militants who seized Parkhurst Hall a doubly agonizing experience for him. Yet, it also was a spur that made him search for a way to thwart violence as a form of political expression while protecting both the students and the institution from unnecessary harm. Thus, after long consultation with counsel and others, he developed a flexible approach to campus unrest, in which the court injunction was employed to curb student violence while yet assuring that the power of civil authorities was used with restraint.

Although the number of students at Dartmouth has been increased only slightly over 25 years, the emphasis on quality, and its cost, is reflected in comparative dollar figures.

When he came to Dartmouth in 1945, the budget was $2.25 million. Last year he presided over a budget exceeding $31 million. Total assets have increased from $31 million to approximately $200 million, including 20 major buildings added during his nearly 25 years. Meanwhile, alumni clubs have increased from 90 to 140, and Alumni Fund giving jumped from $337,000 to more than $2 million last year, and the total endowment rose from $22 million to $147 million. They are figures that underlined the observation of Lloyd D. Brace '25, chairman of the Dartmouth Trustees, that finding a successor to step into President Dickey's shoes presented the Trustees with a major problem.

As the 12th in the Wheelock Succession, following the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock who founded Dartmouth exactly 200 years ago, President Dickey was the eighth alumnus President. Graduated from Dartmouth in 1929 with highest distinction in history and a Phi Beta Kappa key, he went on to the Harvard Law School where he received a law degree in 1932 and for several years was a member of the Boston law firm of Gaston, Snow, Saltonstall and Hunt. He served as assistant to the Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Correction in 1933-34, and later joined the Department of State first as assistant to the Assistant Secretary Francis B. Sayre and later, to Secretary of State Cordell Hull. In 1940 he resigned his law partnership to rejoin the State Department in the Office of Inter-American Affairs, then directed by Nelson Rockefeller '30. After serving as chief of the Division of World Trade Intelligence, he again, in 1943, was named special assistant to Secretary Hull to work on the Trade Agreements Act and provide liaison between the State Department and outside groups interested in foreign policy. In 1944, he became the first director of the State Department's Office of Public Affairs, the position he held when called to Dartmouth. During this period he also served as public liaison officer for the U.S. delegation to the San Francisco Conference on the United Nations Charter, and taught foreign policy formulation at the School of Advanced International Studies.

After becoming President of Dart- mouth, he was named a member of the Presidential Committee on Civil RigWs which in 1947 produced the historic report, To Secure These Rights. In 1951, following outbreak of the Korean War, he was consultant to the American representative to the United Nations, Security Measures Committee, and in 1952 he was a consultant to Secretary of State Dean Acheson on Disarmament.

His continuing interest in international affairs throughout his presidency at Dartmouth was exemplified by the three-day convocation held in 1957 on Great Issues Among Britain, Canada and the United States and later the Canadian and the Japanese Years observed by the College. In 1960, as a contributing author of the book The Secretary ofState, he wrote on "The Secretary of State and the American Public." He is also editor of the book, The UnitedStates and Canada, an American Assembly Spectrum publication issued in 1964 by Prentice-Hall.

Although in recent years he has had to cut back outside assignments, he is or has been a member of the Advisory Committee for the Foreign Service Institute of the Department of State, the Board of Visitors to the United States Military Academy at West Point, the Committee of Advisers to the President of the U.S. Naval War College, the Committee on Studies of the Council on Foreign Relations, the Foreign Policy Committee of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Board of Governors of the Arctic Institute of North America, and the board of directors of Atlantic Council of the U.S.

Also, a trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation, Wellesley College, the Committee for Economic Development, and the Brookings Institution; a director of the National Merit Scholarship Corporation and the Council for Financial Aid to Education; a public governor of the New York Stock Exchange; and a member of the Ford Scholarship Board of the Ford Motor Company Fund, the General Motors Scholarship Committee, and the Public Policy Committee of the Advertising Council.

When he returns to Hanover in a month or so and settles down to the role of President Emeritus, Mr. Dickey will have a faculty office in Silsby Hall because he also will hold the position of first Bicentennial Professor of Public Affairs. He has told friends that he intends to expand his professional interest in international affairs, particularly American-Canadian relations. Mr. Dickey expects to participate in some international relations courses as lecturer, and his plans also call for some writing.

The Dickeys' new Hanover home, which they began to build last year, will not be far from the center of campus activities. There they will have the pleasure of seeing a host of Dartmouth and other friends, and of providing a home base for their three children - John Jr. '63, Sylvia, and Christina (Mrs. Stewart Stearns Jr. '54) - and their three grandchildren.

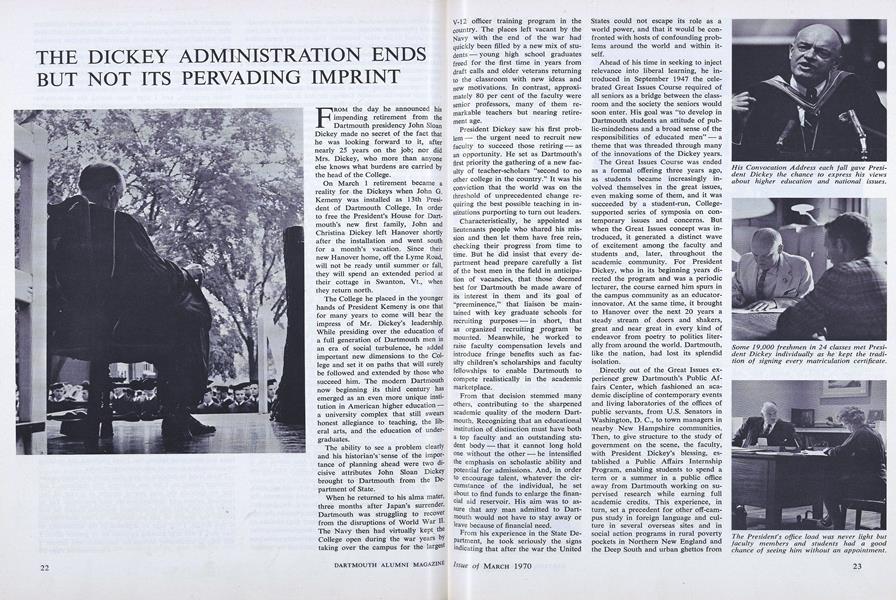

His Convocation Address each fall gave PresidentDickey the chance to express his viewsabout higher education and national issues.

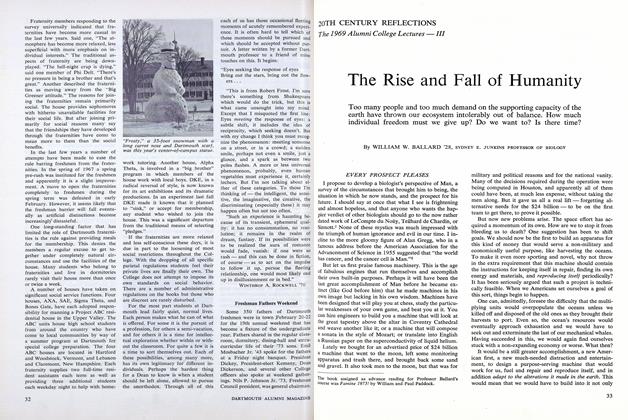

Some 19,000 freshmen in 24 classes met PresidentDickey individually as he kept the tradition of signing every matriculation certificate.

The President's office load was never light butfaculty members and students had a goodchance of seeing him without an appointment.

President and Mrs. Dickey on their visit to Japan in the spring of 1964.

Mr. Dickey helps to dedicate the KiewitComputation Center in Dec. 1966.

President Dickey playing host to President Eisenhowerwho was in New England in 1955.

A favorite spot for escaping the burdens ofoffice has been the Dartmouth College Grant.

Meeting informally with newly arrived freshmenat the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge is somethingMr. Dickey has enjoyed doing each fall

President Dickey receiving the honorary Doctorate of Laws from the Universityof Toronto in May 1968. He has been honored by 17 institutions in all, includingBrown, Columbia, Harvard and Princeton of the Ivy group.

James Ruxin "JOPresident Dickey helping to build last month's center-of-campus snow statuefor Winter Carnival, a job at which he has been faithful over the years.

At the 1970 Boston alumni dinner,which he has addressed almost everyyear, Mr. Dickey received an inscribedclock from Howard C. Smith Jr. '52,president of the association.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Rise and Fall of Humanity

March 1970 By WILLIAM W. BALLARD '28, -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Priorities for 1970

March 1970 -

Article

ArticleThree Students Argue for Coeducation

March 1970 By CHERYL CAREY, Coed, RANDY PHERSON '71, RICHARD ZUCKERMAN '72 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '7O -

Article

ArticleAn Antidote to Hugeness

March 1970 By CARLOS H. BAKER '32 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1970 By EDMUND H. BOOTH, DONALD L. BARR

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

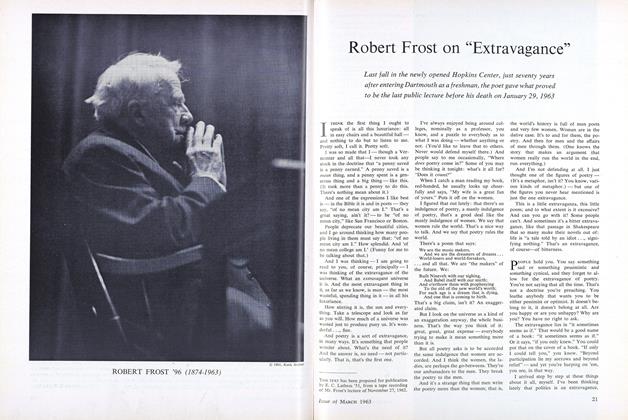

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

MARCH 1963 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTed Wolf '30

March 1993 -

Feature

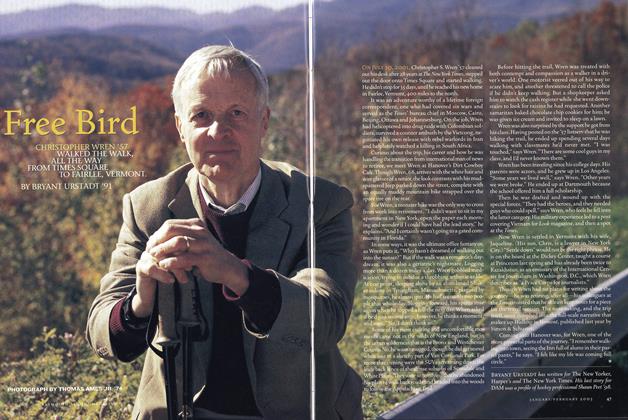

FeatureFree Bird

Jan/Feb 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

OCTOBER 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

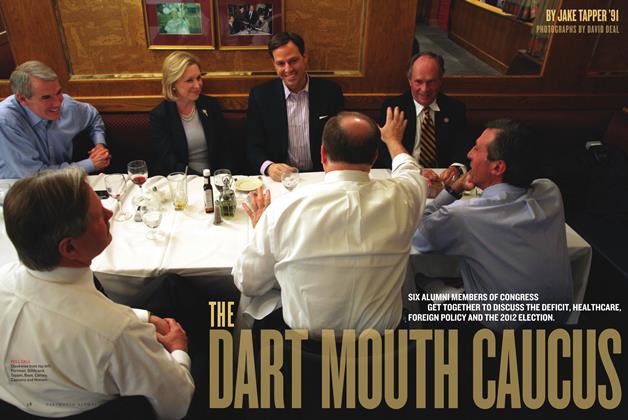

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Caucus

July/August 2011 By Jake Tapper ’91