ASSISTANT TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

I KNOW of no more appropriate way to begin a discussion of Anglo-Canadian-American relations than to repeat the words of Prime Minister Diefenbaker during his first radio and television broadcast as Prime Minister. Referring to the fact that he had almost simultaneously received messages of congratulation from Queen Elizabeth and President Eisenhower, he suggested that the timing of these messages was more than mere coincidence and added: "I consider it very dramatic evidence of Canada's unique position in the Commonwealth under the mystic unity of the crown and of her close relationships to the United States . . . I believe that the unity of these nations must be preserved in the years ahead in a spirit of infinite forbearance and compassion."

I believe that, too, as I am sure do all of us here.

As we recognize the need for unity, however, we recognize also that the fact of unity has required effort to be achieved, and will require further effort to be maintained. Even in cases where our interests are parallel, as in the matter of continental defense, active cooperation rather than mere assent has been required in order that these interests might be fully served. In those cases where our interests may tend to conflict, then the "forbearance and compassion" of which Mr. Diefenbaker spoke, along with hard work, have been required in considerable measure, and will continue to be required, if unity is to be maintained.

A hundred years ago, or a little more, there occurred a series of events which illustrates clearly the need for agreement between our nations, and the processes by which this agreement can be achieved. In 1853 a difference of opinion existed between Canada and the United States with regard to fishing rights in the vicinity of the Maritimes. A naval order issued that year declared that the United States Government had "concluded to send a naval force to cruise in the seas and bays frequented by our fishermen. . .The commanding offlicer's orders were to "take such steps as in your judgment will be best calculated to check and prevent interference," and concluded, "Your mission, Commodore, is one of peace; but while you do nothing to provoke war, you will do nothing to jeopard our rights or compromit our honor."

This rather stiff-necked approach was, in those prenuclear days, merely a conventional way of frowning at each other. (That was when we could still afford to miscalculate in matters of peace and war.) But the fact that frowns seemed necessary shows clearly that the fact of our geographical proximity alone has not guaranteed our good relations.

About a year after the episode of the naval order the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 was signed, removing this and other sources of friction. . . . Edgar Mclnnis, the Canadian historian, who honors this convocation with his presence, gives this verdict on the outcome: "The result of the treaty was a period of progress toward closer economic cooperation which, paradoxically, strengthened the forces of political separatism and brought still nearer the achievement of a distinct national status by British North America."

The lesson seems to me inescapable: that by the realism of our cooperation in matters where cooperation was appropriate we mutually increased our strength, and thereby enhanced our independence.

A full century in Canadian-American relations has intervened since certain problems of that day were dealt with in the Treaty of 1854. Despite the success of our efforts then and since, we have today a new set of problems. (One of my colleagues defines progress as that condition in which problems facing him today are different from those he faced yesterday.)

On our economic horizon some thunderclouds have gathered.

It is a plain fact that our two countries are currently in a surplus position in wheat. Our farmers are doing better at their job of producing than the rest of us are doing at ours. I would not for a moment assert that we have in every case succeeded in our surplus disposal efforts to avoid unintended consequences for our friends. I can say, however, that earnest efforts by earnest men are constantly being made to dispose of those price-depressing surpluses with full regard to the interests of our friends. But we must do better. A more concerted approach in this area could be productive of still better results.

In many respects our economies are complementary, in some respects competitive. Surely our mutual interest is in freely flowing trade. Irritations have arisen, for instance, in the marketing of potatoes, dairy products, strawberries, fish fillets, oats, rye, barley, lead and zinc. I am sure we shall never be altogether lacking in irritations; but, in respect to each, as it occurs, the urgency and nature of the exigency that confronts us must be recognized. In perspective, there are really very few actions that are taken which seem inimical to the national interest of our neighbor. They must be the exceptions, reluctantly made, to the rule of removing unwarranted obstacles to the freedom of trade and investment. Fortifying economic frontiers against one another can only lead to rechanneling of trade which imposes a penalty upon both of us and to acrimony which aggravates our national feelings out of all proportion to reality.

Enduring friendship between nations, as indeed between friends, can be no casual, capricious relationship. Friendship can be sustained only by effort and dedication: effort, in our case, not only to emphasize areas of affinity, but also to smooth and staunchly resolve the changing issues which sometimes quicken the national pulse; dedication not simply to the common heritage and traditions that bind together our people, but dedication to the task of finding common ground on which we can profitably stand, whether it be in the area of defense, tariffs and trade, or whatever ground on which we seek to stand together.

The preservation of a lively friendship is no mean task. It certainly involves some appreciation of the impact of our national conduct upon the other fellow, and what the results of that conduct may be upon his welfare and upon his pocketbook. A community of heritage, blood ties and ideals are the footings upon which our firm alliance stands. Yet this edifice must be more than a whimsical affection that we have for each other. It must take into account the difficulties in each other's national family which stir up and weaken us for vastly more important and far-reaching responsibilities. . . .

The world has changed in a thousand ways since negotiations of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, and our two nations have been not least in changing. Yet for all essential elements which are different today, there is at least one which remains the same. If there was then a sense of partnership between us, and a growing sense of interdependence between all three of us, together with a keen feeling of the need for mutual strength and cooperation, there is no less such a sense of feeling now. If resolving issues then required time and great effort, there is no reason to doubt that resolving today's issues will require still more. If the successful resolution of foreign policy questions in that age demanded the exertion of great ingenuity and infinite patience, we must assume that the resolution of today's problems demands no less. If realistic cooperation on matters of joint interest in those times did not decrease the dependence of each nation, but increased it, then the presumption is warranted that similar cooperation will have equivalent results today.

If the world in this promising but perilous era needs to learn any single lesson it is that peaceful means can be found for resolving differences. While preserving the integrity of our own national institutions we can live in peace together in the same world. And if such a national policy works for us it can work for others. We of the Anglo-Canadian-American Community can teach and live this lesson if anyone can. That, for a century and a half we have done. That, I believe, we shall continue to do.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

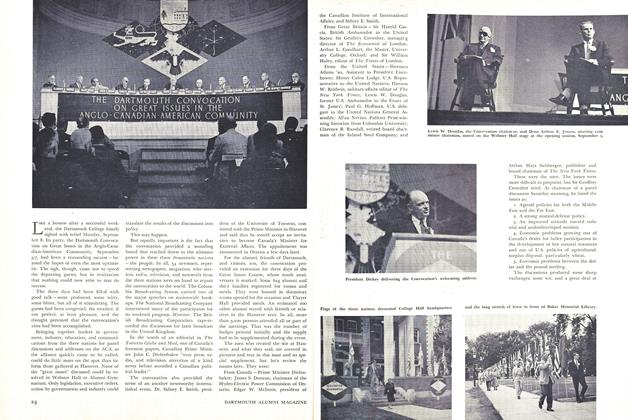

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWho will teach them?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWill they graduate?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

MAY 1996 -

Cover Story

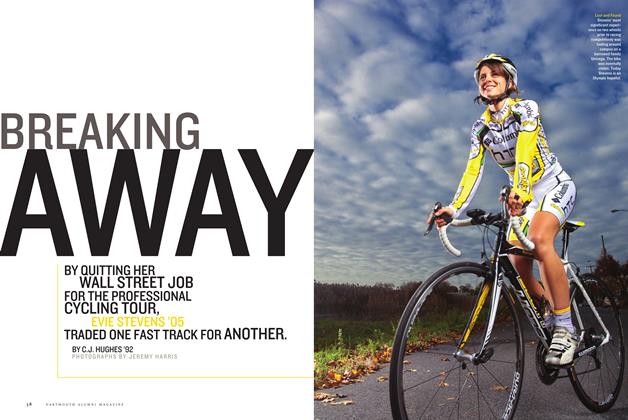

Cover StoryBreaking Away

Jan/Feb 2011 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Cover Story

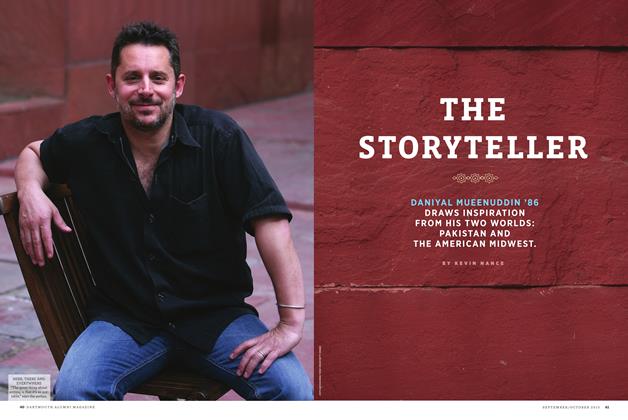

Cover StoryThe Storyteller

September | October 2013 By KEVIN NANCE -

Feature

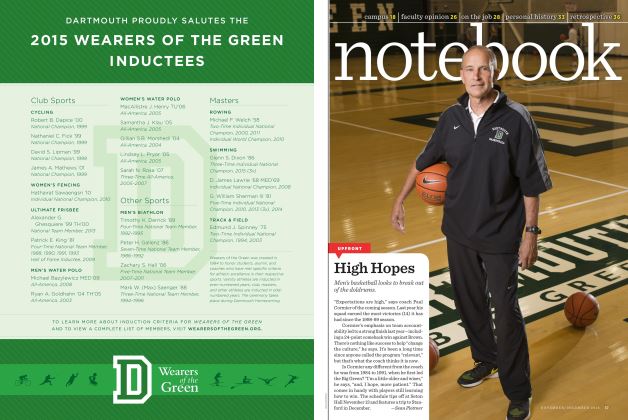

FeatureNotebook

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By SHERMAN JOHN