By James H. Wheatley '51. Cambridge,Mass.: The M.I.T. Press, 1969. 157 pp.$7.50.

Patterns in Thackeray's Fiction: the title is auspicious. For too long, both laymen and critics often dismissed Victorian novelists as haphazard and superficial. Admittedly, Dickens, Trollope, and their contemporaries were frightfully prolific. Often they wrote too swiftly, spurred by the financial and temporal pressures of serial publication. But the almost languid narratives that resulted conceal a careful craftsmanship. If they are, as Henry James said, "baggy monsters," Thackeray's novels are also meticulous tableaux.

For a century after Vanity Fair, critics failed to respond to this artistry. James H. Wheatley, like Geoffrey Tillotson before him, is alive to the challenges Thackeray poses. He enjoys a firm understanding of the intellectual milieu of the period, and in his introduction he makes a telling point about the Victorians at mid-century: "Whole attitudes that had been implicit and acceptable - implicit partly because they were acceptable - were now beginning to have names and with names, attackers and defenders." The tacit consensus that shaped Thackeray's fiction began to dissolve, eroding the author's self-confidence and daring. Yet that gentleman's consensus, while it lasted, was dynamic and powerful. Because of the cluster of unquestioned verities that existed before 1848, Thackeray could imply, evoke, and show what muckrakers and Marxists, reformers and evangelists, would have him say. When the intellectual idiom of Victorian England became explicit, as in Tennyson's flag-waving conclusion to "Maud," it became strident. The axiomatic Victorian conservatism gave way to a baffled and belligerent imperial pride.

Wheatley's critical approach suits Thackeray's pointillism. He begins with the early parodies, writing that Thackeray the parodist assumed that language revealed character. This is central to Wheatley's thesis that "Thackeray's greatness lies in his style, and it can lead to a profitable speculation about the nineteenth-century novel in general. Professor Wheatley proceeds to read the. major novels intensively. The unifying scheme in his whirlwind tour of Thackeray's detailed, panoramic fictional universe is to recognize, in so formal an art, the life 0 the ego in action."

Wheatley shows how well satire and realism mesh in Vanity Fair. He tries to isolate its emotional center in an illuminating contrast to Jane Eyre. His discussion of Pendennis, Henry Esmond, and The Newcomes pivots on an interesting composite portrait of the Thackerayan tyro. An examination of Thackeray's novels as secular prayer is provocative. And Wheatley demonstrates commendable sensitivity to the historicism of the novelist who called time "the grey satirist."

Wheatley explores more than concludes, but he has produced an original and stimulating study of the artistic rhetoric and moral meaning of Thackeray's novels.

Mr. Paul, who was valedictorian of theClass of 1969, currently teaches English atConcord (N.H.) High School. His SeniorFellow thesis was on Thackeray.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dilemma of World Power

April 1970 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureRevival of the M.D. Degree

April 1970 -

Feature

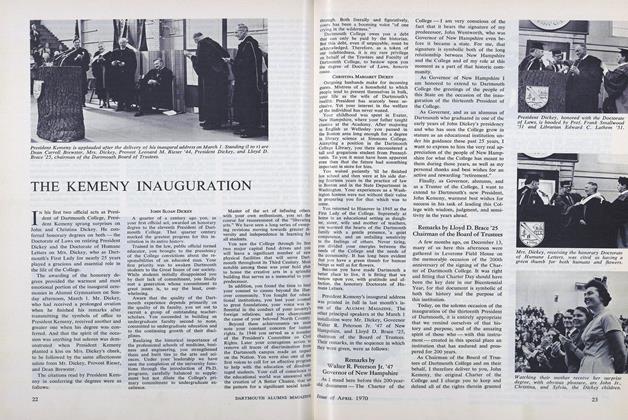

FeatureTHE KEMENY INAUGURATION

April 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe National Scene

April 1970 -

Article

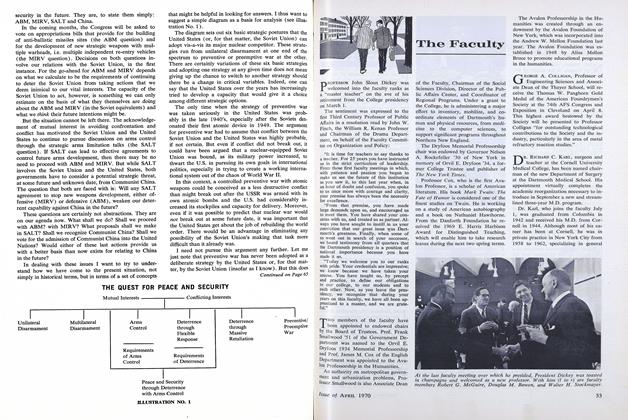

ArticleThe Faculty

April 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

April 1970 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, GEORGE PRICE

KENNETH PAUL '69

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

OCTOBER 1969 -

Books

BooksWEIRD AND TRAGIC SHORES: THE STORY OF CHARLES FRANCIS HALL, EXPLORER.

JUNE 1971 By KENNETH PAUL '69 -

Books

BooksTHE STICKS: A PROFILE OF ESSEX COUNTY, NEW YORK.

JANUARY 1973 By KENNETH PAUL '69 -

Books

BooksTHE MYTH OF THE MIDDLE CLASS NOTES ON AFFLUENCE AND EQUALITY

APRIL 1973 By KENNETH PAUL '69 -

Books

BooksIndividuals Alone

SEPT. 1977 By KENNETH PAUL '69 -

Article

ArticlePatience Rewarded

JUNE 1978 By Kenneth Paul '69

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE STRIDE OF TIME.

APRIL 1967 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksThe Nuclear Dilemma

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By BERNARD D. NOSSITER '47 -

Books

BooksAN ADVENTURE IN TEXTBOOKS.

MARCH 1970 By DENNIS A. DINAN '61 -

Books

BooksA FURTHER RANGE

October 1936 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Books

BooksNEIGHBORHOOD GROUPS AND URBAN RENEWAL.

JULY 1966 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksTHE EPIC OF INDUSTRY

JUNE, 1928 By Robert E. Riegel