HastingsLyon '01. John Felsberg, Inc., New York.1944, pp. 146.

The main thesis of this book is that a program of governmental borrowing and spending is a bad way to decrease "involuntary unemployment," and that a better way is to set the price of labor where it will clear the market. One great trouble with leaning on inflation (even where we assume that the government's deficit financing will produce the inflation) is that it lowers the wages of all units of labor collectively. It is preferable, the argument runs, to adjust the supplyprice schedules of each of the different types of labor. That inflation alone will hardly turn the trick is not likely to be denied by economists, to whom chiefly, to judge by its composition, the book is addressed. The question, rather, would be what sort of adjustment the author recommends.

Here one is not left long in doubt about the point of view which is to color, or discolor, the whole discussion. In the first chapter the author defines "involuntary unemployment" in such a way that you are voluntarily unemployed if you decline any job whatever at any wage whatever, no matter how low. It makes a difference whether this definition is accepted. The present reviewer could not recommend it without "lying like an epitaph." If you are idle because you demand more than your services are worth, you are responsible for your unemployment. Fair enough. But "suppose you turn down a job because the employer insists on wages which are below what your work is worth? Lo, you are still to blame for your idleness! Quite apart from "blaming," which is not the main point, this does not make sense. It is not economics. The object is to allocate productive power, including labor, as economically as possible. For this purpose, labor should be priced at what it is worth. If it is priced higher, employers cannot afford to use it. If it is priced lower, then either laborers are discouraged from working or else employers are permitted to use labor in relatively unimportant jobs. The author ought to be the first to see this, since he has so defined "employment" as to make it practically synonymous with "production." Any definition of involuntary unemployment which ignores it sheds darkness on the central problem.

No doubt deficit spending has pitfalls enough, and certainly the author displays subtlety in his attack on some of them. Yet a curious selection of assumptions now and then tends to discredit the general thesis. To take another instance, the author chooses to stress, as a determinant of saving, the will to save rather than the ability to do so. And then, perhaps by way of being consistent, he goes on to treat the willingness to have children as a case of unwillingness to save. One of our most trying problems after the war will be that of dividing rights and duties wisely between employers and laborers. If it is made harder by the tendency of organized labor to seek rights without duties, it will not be made easier by treatises which justify employers in doing the same thing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

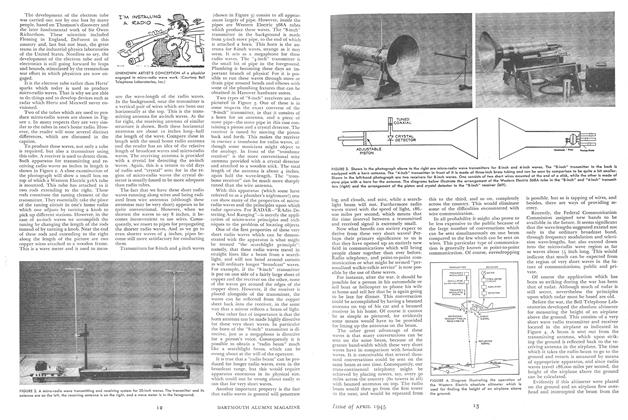

ArticleRADIO WAVES AND RADAR

April 1945 By GORDON FERRIE HULL JR. '33, -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

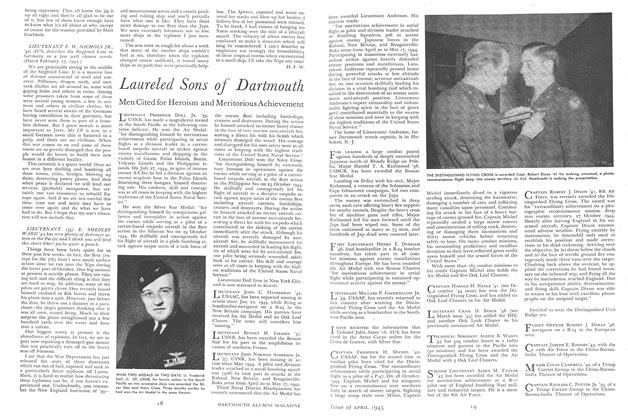

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

April 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

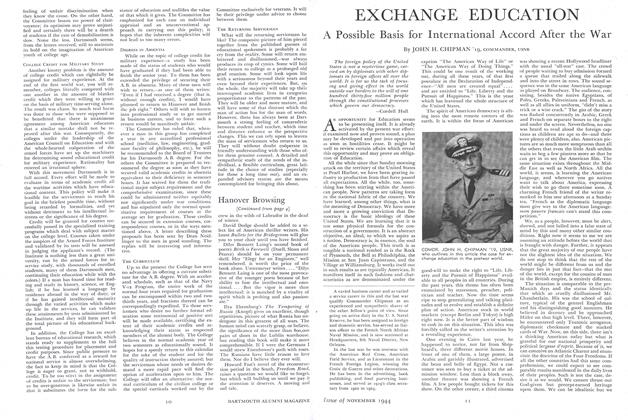

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1945

Bruce Knight

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Authors

November 1944 -

Books

BooksThe December 5 issue of Far Eastern

January 1946 -

Books

BooksMRS. BRIDGE.

FEBRUARY 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksElusive or Realizable?

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Elise Boulding -

Books

BooksAREA STUDIES IN AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES,

February 1948 By George L. Scott '25. -

Books

BooksTHE MYSTERY OF THE APOSTLES

October 1935 By William H. Wood