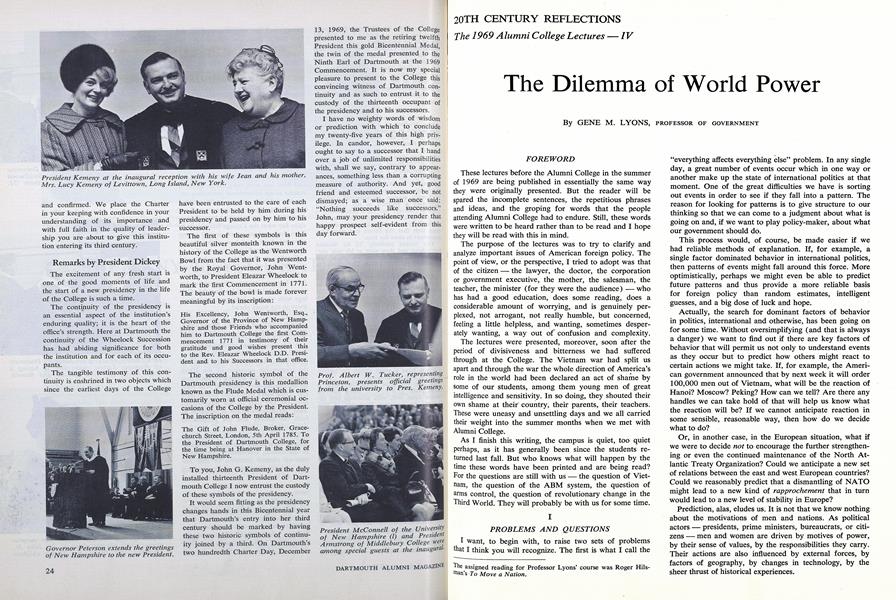

20TH CENTURY REFLECTIONSThe 1969 Alumni College Lectures - IV

PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

FOREWORD

These lectures before the Alumni College in the summer of 1969 are being published in essentially the same way they were originally presented. But the reader will be spared the incomplete sentences, the repetitious phrases and ideas, and the groping for words that the people attending Alumni College had to endure. Still, these words were written to be heard rather than to be read and I hope they will be read with this in mind.

The purpose of the lectures was to try to clarify and analyze important issues of American foreign policy. The point of view, or the perspective, I tried to adopt was that of the citizen - the lawyer, the doctor, the corporation or government executive, the mother, the salesman, the teacher, the minister (for they were the audience) — who has had a good education, does some reading, does a considerable amount of worrying, and is genuinely perplexed, not arrogant, not really humble, but concerned, feeling a little helpless, and wanting, sometimes desperately wanting, a way out of confusion and complexity.

The lectures were presented, moreover, soon after the period of divisiveness and bitterness we had suffered through at the College. The Vietnam war had split us apart and through the war the whole direction of America's role in the world had been declared an act of shame by some of our students, among them young men of great intelligence and sensitivity. In so doing, they shouted their own shame at their country, their parents, their teachers. These were uneasy and unsettling days and we all carried their weight into the summer months when we met with Alumni College.

As I finish this writing, the campus is quiet, too quiet perhaps, as it has generally been since the students returned last fall. But who knows what will happen by the time these words have been printed and are being read? For the questions are still with us - the question of Vietnam, the question of the ABM system, the question of arms control, the question of revolutionary change in the Third World. They will probably be with us for some time.

I

PROBLEMS AND QUESTIONS

I want, to begin with, to raise two sets of problems that I think you will recognize. The first is what I call the "everything affects everything else" problem. In any single day, a great number of events occur which in one way or another make up the state of international politics at that moment. One of the great difficulties we have is sorting out events in order to see if they fall into a pattern. The reason for looking for patterns is to give structure to our thinking so that we can come to a judgment about what is going on and, if we want to play policy-maker, about what our government should do.

This process would, of course, be made easier if we had reliable methods of explanation. If, for example, a single factor dominated behavior in international politics, then patterns of events might fall around this force. More optimistically, perhaps we might even be able to predict future patterns and thus provide a more reliable basis for foreign policy than random estimates, intelligent guesses, and a big dose of luck and hope.

Actually, the search for dominant factors of behavior in politics, international and otherwise, has been going on for some time. Without oversimplifying (and that is always a danger) we want to find out if there are key factors of behavior that will permit us not only to understand events as they occur but to predict how others might react to certain actions we might take. If, for example, the American government announced that by next week it will order 100,000 men out of Vietnam, what will be the reaction of Hanoi? Moscow? Peking? How can we tell? Are there any handles we can take hold of that will help us know what the reaction will be? If we cannot anticipate reaction in some sensible, reasonable way, then how do we decide what to do?

Or, in another case, in the European situation, what if we were to decide not to encourage the further strengthening or even the continued maintenance of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization? Could we anticipate a new set of relations between the east and west European countries? Could we reasonably predict that a dismantling of NATO might lead to a new kind of rapprochement that in turn would lead to a new level of stability in Europe?

Prediction, alas, eludes us. It is not that we know nothing about the motivations of men and nations. As political actors - presidents, prime ministers, bureaucrats, or citizens - men and women are driven by motives of power, by their sense of values, by the responsibilities they carry. Their actions are also influenced by external forces, by factors of geography, by changes in technology, by the sheer thrust of historical experiences.

All these forces, moreover, act on each other and any general model of interaction must bear the critical tests of time, culture, and ideology. The importance of geographic position in international politics, for example, is sharply affected by advances in technology - witness the impact of missiles of intercontinental range on the protection that the two oceans historically provided for the United States. Similarly, the historic interests of Russia become complicated by the ideological impulses of communism. The mix of national interest and ideology, moreover, shifts with changes in the external environment and with the internal politics of other communist nations.

The fact is that we can isolate the major factors of international politics. What is more difficult is to discover general principles that will tell us how these factors act upon each other. This difficulty is complicated by prob- lem number two: the "pictures in the mind" problem. "Pictures in the mind" is the felicitous phrase invented many years ago by Walter Lippmann. It refers to the screen of preconceived notions through which we filter our understanding of events as they occur - our perception of reality, if you will.

Let me try to illustrate the problem of "pictures in the mind" by inviting you to play an old parlor game. What are your first reactions to key symbols? What comes to your mind immediately when I say China? when I say Russia? the Soviet Union? Do you think of something different when I say "Russia" than when I say "Soviet Union"?

The relevance of the "pictures in the mind" problem becomes evident when we try to think out an issue like the ABM. Many of you may have followed the debate on the ABM in the Congress. You will remember that much of the debate centered around the comparative capacities of the United States and the Soviet Union with regard to both offensive and defensive military systems. There were obvious gaps in information about the present and future capabilities of the Soviet Union, but these were gaps that could be filled in by reasonably intelligent (though not uncontroversial) projections on the basis of known information.

But the capability of the Soviet Union was not the only factor involved in trying to come to a conclusion about what to do about the ABM. Also involved was the question of Soviet intentions and it is here that "pictures in the mind" operate most forcefully. When we are asked to estimate Soviet intentions at some unknown future date, there are undoubtedly reference points that can help us. We might estimate future intentions by the history of past actions, or at least our understanding of past actions. But even here, the links are complicated. Do we judge the future by our "picture" of the Soviet Union under Stalin? under Khrushchev? under the present leadership of Kosygin and Brezhnev?

Or do we judge future Soviet intentions by an estimate of changes that might occur in the Soviet Union and the kind of leadership that might emerge? If we do, then we have to identify the nature of these changes, the probability of their coming to pass, and the sources of their generation. In all these speculations, there are a great many variables, factors that depend on unknown and perhaps unknowable shifts and patterns. In dealing with these factors of social, political and economic change, there is thus less that is sure than when we try to project military capabilities that are governed by largely technological possibilities.

When we deal with Soviet intentions, therefore - or, to make the case even stronger, with Chinese intentions — the range of responses is subject to great variation and the values given to probabilities are bound to be influenced by our "pictures in the mind." The less we know, of course, the more powerful will be the effect of these "pictures." But even where knowledge or information is reliable, even when we read and try to understand, there is bound to be a process of synthesis and projection which is conditioned by our life experience, by the notions of human nature we harbor, and by the reflexes we have developed to the phenomena of "Russia," "Communism," and "China."

Now I speak of these two sets of problems - "everything affects everything else" and "pictures in the mind" - because I think it is important to be aware of them before we try to understand and discuss the pressing questions of American foreign policy today. We should be aware of what we will be going through, the difficulties we are going to face in trying to be as objective and analytical as possible in dealing with four questions that, in one way or another, expose the range and intensity of the present dilemma of American foreign policy.

First, what posture should the United States adopt in its role in world politics after Vietnam? There are two extreme answers to this question. At one end, there is a posture of interventionism, or of becoming what many have called the "world's policeman"; at the other, a posture of isolationism, of returning to the alleged policies the United States followed after the first world war, or, in other terms, retreating into a "Fortress America."

If neither of these extreme strategies seems plausible, or desirable, each nonetheless could be justified. If there is any meaning to our Vietnamese experience, it is that the role of world policeman has grave dangers and may not be tolerated because of the strains it places on American society. And yet what is the alternative except a world of anarchy? or a world in which forces inimical to American interests can move into critical areas without opposition or fear of reprisal? The structures of international authority are weak; the differences between world powers are unlikely to disappear; and the forces for revolutionary change are ferocious. If the United States does not assume responsibilities for world stability, then chaos will result. And in chaos there is no protection for American interests (however they are perceived).

On the other hand, there may be real doubt (which Vietnam would seem to support) that the United States can effectively play the world's policeman. In the process of trying to do so, moreover, the United States can exhaust its economic resources, its political credibility and, indeed, its collective soul. For, in playing policeman, the United States can too easily find itself supporting the status quo and inhibiting important social changes. From a practical viewpoint, the United States does not need the world, could maintain a high level of material progress without international involvement, and would do well to turn its most creative energies to solving its domestic ills.

But the choice we have is not necessarily between interventionism and isolationism. And if I believed in prediction, I would predict that we will follow neither strategy in the future. We are more likely to follow some posture in between the two extremes. For the moment, it does not matter what the precise nature of that strategy will be. Whatever it is, it will require the necessity of choosing when, where and how we will become involved in the affairs of other nations. If the United States ever got caught up in a policy of pervasive and indiscriminate interventionism, it is over. By the same token, it is hopeless to think of the United States isolating itself from the main currents of world events. Even if we wanted isolation, others would not permit us this retreat.

But how do we go about deciding when, where, and how we will seek to influence the course of international politics? To which countries do we offer economic assistance? Under what conditions do we promise military protection? It is often convenient to answer questions like these by replying that we should make such decisions on the basis of our national interests. The national interest is an important yet seductive concept in international politics. It suggests a reasoned and careful analysis of pros and cons and a hard-hitting yet humane diagnosis of the situation. Yet, for all of this, saying that we should act in our national interest still does not tell us what our national interest is, or how one can go about finding out. We are left with the problem of articulating the criteria we will use in choosing among alternative ways of acting, and this problem leads to a second question: What should be the goals of American foreign policy?

Resorting to questions of goals is not an uncommon response to a dilemma. It can also be interpreted as a non-response. But surely there is no way of remotely measuring progress, or providing a base point for deciding how to act, without some notion of objectives, even if they are neither eternal nor ultimate. One problem is that we have to think of multiple goals and once we begin to articulate more than one goal, we often find that our goals may be potentially as conflicting as they are complementary.

I am reminded of the slogan that is used in many military installations: "peace is our business." In many ways (and for many people) this slogan is a contradiction and even hypocritical. Yet it is a good example of trying to reconcile the twin goals of peace and security that are legitimate objectives of American policy. The maintenance of a large military establishment is essential to American security. It is an instrument for maintaining a balance of power in the world and, through such a balance, a relative and precarious peace. Yet a military establishment is also an instrument for waging war in the name of security. When do the demands of security outweigh the demands of peace?

The question of goals, moreover, is wound up with the question of means. Indeed, the goals-means relationship is classic in all matters of human affairs and no less in matters of foreign policy. In simplified terms, we cannot hope to achieve objectives if we do not possess the means that are required. At the same time, the fact that we have the means today to bomb Communist China with nuclear weapons without fear of effective retaliation (from that country) does not necessarily provide a rational objective for American foreign policy. It provides an alternative choice, however - a choice we would not have if we did not possess certain capabilities.

The goals-means relation inevitably brings us up against the costs of foreign policies, costs not only in material or financial terms, but also in human terms, and in terms of values as expressed in the priorities we set for ourselves. There is much talk today about a possible distortion in the priorities of American society. This distortion is usually illustrated by contrasting the costs of the Vietnam war or the costs (whatever they are!) of the ABM system with the smaller sums being allocated to the rebuilding of cities, the protection of the physical environment, or the growth of educational facilities. This contrast is sometimes pictured against a fixed budgetary pie and the questionable assumption that savings that might be gained by ending the Vietnam war will be transferred to other programs. The national budget is not fixed, however, and increases in budgets for public housing and education will have to be earned through effective political action with or without Vietnam.

But the question of national priorities is nonetheless valid and critically important and is the third question that we need to keep in mind during these discussions: What should our national priorities be? What this question does, moreover, is to remind us that questions of foreign policy are questions of domestic politics as well as of international politics. Indeed, there is no meaningful line between our national life and our role in world affairs. How could it be otherwise?

The three questions I have posed thus far are clearly linked. The question of our international position after Vietnam is related to the goals we choose to pursue, goals that are influenced by our capacity and willingness to provide the means they require for success. By the same token, our role in world politics will affect, and be affected by, the quality of our society and the sense of urgency and the values we attach to our own lives. Even in the stating, I trust that you recognize the difficulties I feel any of us must have in answering these questions. It is for this reason that I am led to pose a fourth question that might be the most important of all.

If the future role of the United States will require decisions of choice, if the criteria of choice must be based on goals that are at best ambiguous and often conflicting (or at least in tension), and if the pressures for choosing among alternatives come from the internal strains of American society no less than the external demands of world politics - if the problems of choice are so wrapped up, then: How will the United States go about deciding questions of foreign policy? Who will decide?

I do not raise the question of who will decide as a way of avoiding a direct response to the first three questions. I raise the question of who decides because I think it should be high on our agenda. There are no determinable answers to the earlier questions; there is only a choice among alternatives. Who decided that the United States should send military advisers to South Vietnam? Who decided that these advisory groups should be supported by American combat troops? Who decided that the United States should launch air attacks against North Vietnam? Who decided that these air attacks should be halted? Who decided to threaten a nuclear attack against the Soviet Union during the Cuban missile crisis? Who decided that the defense of West Berlin is a firm and indivisible commitment on the part of the United States? Who decided the conditions under which the United States would, or would not, sell arms to countries in the Middle East? Who decides our national interest in these and other questions? Who decides our goals? whether we have the means of carrying out our goals? what the effect will be on our priority of values?

I do not raise these questions at this point with any purpose except to emphasize the importance of: who decides? Perhaps it passed through your mind that an obvious answer to most of the questions is "the President." But it should also be obvious that the answer is neither so simple nor so neat. President Truman used to say that "the buck stops here" and it does. The President has no one to whom he can pass along the question, whatever it is. Nor does he have anyone he can blame for his mistakes. If he acts on bad advice, it is nonetheless he who acts.

But the President does not act in isolation from his political associates, from the constitutional processes of checks and balances, from the prevailing mood of the country. There has certainly been a centralization of decision-making since the second world war, especially in matters dealing with foreign affairs. But I see no evidence (as some might contend) that it has come about through any conscious attempt at usurpation of power. It has come about through the nature of the issues we have faced. Crisis management, the demands for secrecy, and the mobilization of expert knowledge have all tended to shift the balance of power in decision-making from the legislature to the executive.

These are facts of life. It is also a fact of life that a widening, or broadening, of the decision-making process does not necessarily lead to what one might call enlightened policies. Open congressional debate on matters of defense, for example, has often demonstrated a frightening level of bellicosity. At the same time, it is fair to judge that the influence of congressional and public debate on economic assistance to developing nations has been to limit, rather than expand, the scope and impact of American programs.

The question nevertheless is a question of the democratic process. We can be interested in the democratic process without assuming that democratic societies are inherently humane, generous and wise. Still, we live with the hope that this society of ours can be humane, generous and wise. We understand the reasons why decision-making has become centralized. We see the Congress seeking to reassert itself in making a more positive and inquiring role in the recent hearings on Vietnam, the ABM, and the military budget. And whether or not we ourselves feel alienated, we hear many people in our society, particularly young people, deploring their isolation from decision-making and, in the extreme, threatening to destroy the whole system.

The question of who decides, therefore, cannot be avoided. It is of considerable importance to a group like this, since I assume that most of you come as citizens. And as citizens, what is the use of trying to understand if there is no opportunity to affect the direction of foreign policy? Why bother worrying about these questions if no one cares what you think? Or even if they do care, why bother if what you think does not and cannot matter because of the overwhelming influence of other forces on decision-makers? If we are here to think about foreign policy, then surely we cannot, must not, ignore the question of who decides.

II

A FRAMEWORK FOR HISTORY

"Everything affects everything else" but, if we look carefully, the situation might not be quite as hopeless as that general rule suggests. What I want to argue is that, in any particular period of history, certain forces affect the character of the times more than others. And so it is for the period of history through which we are passing. History is a continuous process and there really are no absolute marking points. But I trust that my colleagues in the History Department will permit me to designate the second world war as a critical point of departure for new forces - or new configurations of historical forces - that continue to shape the world we live in.

I am thinking of three forces especially that not only are fundamental in their effects but provide the bases for developing an analytical framework through which to understand and to try to deal with the contemporary issues of American foreign policy: science and technology; the break-up of the colonial empires and the emergence of a new nationalism; and the state of relations - by now a mix of conflicting and mutual interests - between the great nuclear powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. These forces are pervasive; they are inter-connected; they carry distinct characteristics that set them off from similar forces in other periods of history.

Science and technology, for example, have always been effective engines of social change. But certainly there are clear differences that govern the impact that science and technology have on international politics today. There is, for example, a compression of time between the discovery of new knowledge and its technological exploitation. As a result of the capacity of advanced industrialization, moreover, the technological exploitation of science is massive, so massive that its effects are global in scope. This range of impact, in consequence, leads to revolutionary and often unanticipated changes in the lives of people everywhere.

An immediate effect of science and technology is on the nature of war. War has been so prevalent in history that it seems almost essential to the human condition. But nuclear weapons and long-range delivery systems now have combined to make war between the superpowers unthinkable. There is literally no way in which either nation can rationally calculate effective gain in the aftermath of a thermonuclear holocaust. Yet this situation has led both major nuclear powers to adopt strategies of deterrence in their relations with each other. Rather than renouncing the use of force, strategies of deterrence require the maintenance of large stockpiles of nuclear weapons and delivery systems in a state of constant readiness. It is paradoxical that if these weapons have to be used, deterrence would have failed; yet the success of deterrence, for either side, depends on the belief (by the other side) that they will be used.

There are greater complications in the nature of war that I will want to talk about later. If nuclear war is unthinkable, human conflict unfortunately is as persistent as ever. But war is not the only function of society that has been dramatically transformed by science and technology. The growth and spread of medical services, for example, have had historic results. High rates of infant mortality and periodic losses of large populations through disease and epidemic need no longer be accepted as inevitable tragedies. But these great gains have their side-effects. The preservation of human life is one factor in expanding population pressures in a time of painful economic and social development in many parts of the world. Population pressures in turn raise heavy demands on the production and distribution of food supplies. There are potential solutions for population control and for achieving a balance between food and population in the extension of existing and future technological capabilities. But "technological fixes" are not only constrained by systems of international power and by traditions of national history; they can also seriously disrupt political, sociological, and psychological patterns and, in the process of solving one set of problems, open up a Pandora's box of unforeseen consequences.

It is possible that modern science and technology may have unleashed more than we can cope with. There are some in this country, and elsewhere in the world, who would like to shut off the tap. "Stop the world, I want to get off." There is an anti-technology feeling that carries serious strains of anti-intellectualism and, when observed carefully, troublesome anti-democratic tendencies. Technological progress can certainly no longer be accepted as automatic and benign, to be valued without question. For progress in communications, transportation, production and distribution has brought with it pollution, psychological stress, individual alienation and, for many, loneliness and fear. In terms of international politics, it also has raised doubts about our capacity to deal with the global implications of science and technology within an international system of nation-states.

There were many thoughtful people who predicted the end of the nation-state system when the first atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They correctly assessed the significance of this event on the nature of war and international politics. But assessment and prediction are two different matters; the nation-state survives and the force of nationalism seems stronger and more effective then ever. There are several reasons for the persistence of nationalism. One of the most important is the end of the old colonial regimes and the emergence of new states as legally independent sovereignties. For the new nations of the Third World (as well as many older nations, especially in Latin America) nationalism is a rallying point for differing factions, a symbolic force for mobilizing human effort, a reality that provides a link between the individual and his identification beyond himself in the process of economic and social development.

These are phenomena we can understand. At this level, it is difficult to speak of nationalism as an evil, as obsolete, as unrealistic. But the fact remains that nationalism, not only in the Third World but everywhere, contributes to a disintegrated world system. Whatsoever you may have thought of the old colonial empires, they provided a certain integrating force in world politics that has disappeared with their breakup and the rise of the new nationalism. What is ironic is that this disintegration has come at a time when the effects of science and technology require an integrated global response if they are to be controlled. In a less complicated world, a small number of European powers, ruled by men who had ties of class and status across national lines, provided a worldwide network for change and transfer; they could settle major issues of conflict and disruption, if they wished, through reasonable compromise within a framework of shared values and interests.

But this cozy club is gone. And the worldwide networks of the colonial empires have been dismantled. What vestiges are left serve especially narrow and particular interests, n ot the world community. The end of empire was, of course, in sight for many decades. Indeed, a steady motive behind the establishment of the United Nations and its system of specialized agencies, international conferences and operating programs was and has continued to be the creation of a new set of global patterns through which many of the functions of the old colonial regimes could be performed. There is, however, an essential difference: the colonial systems were based on relations between unequal participants; the U.N. system is based on a relation of equality among all peoples, though the primary unit through which equality is expressed is the nation-state. .

The aim is admirable. Equality among nations is, however, a questionable reality when one contrasts the newest and smallest of African states with mighty nuclear powers. The possibility of arriving at consensus as the underpinning for an integrated world is difficult and even frustrating with so many voices in the debate; ideologies, historical experiences, cultural backgrounds, and political instability, all combine to churn up differences rather than to mold the common interest of humanity.

In somewhat simplified terms, we are confronted with a world that requires a global response to the issues raised by modern science and technology but is suffering through a period of serious political disintegration. In such a situation, some kind of resolution, even of a transitory nature, might be possible through positive and concerted action by the major powers, in this case the United States and the Soviet Union. But for most of the years since the second world war, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. have been in a dangerous state of "enemyship," a relation which has tended to worsen rather than alleviate the problem of disintegration. In recent years this state of enemyship has changed, become more complex, as the two superpowers seem to have become more aware of common interests that they and they alone share, simply because they are the superpowers. How this sense of mutual interest will shape their relations in the future is not altogether clear. It could be a positive force toward political integration. It is, however, disturbed in important ways by the looming uncertainties wrapped in the rise of Communist China as a major world power.

These three forces seem to me to be of primary importance in understanding, and giving perspective to, the international events and issues we have to deal with. They emerged in their present form out of the historical developments of the second world war, though their roots go deeper. They are dynamic, changing, adjusting, interacting, but nonetheless persistent and pervasive. I would like to demonstrate how they have evolved since the war and, in so doing, try to suggest a scheme of analysis that might accomplish three purposes: (1) to clarify the trends in world politics during the past twenty-five years; (2) to sharpen our understanding of the changes we are currently witnessing; and (3) to relate these trends and changes to the questions of American policies and strategies "after Vietnam." In doing so, we might be able to see the world in somewhat sharper focus than is suggested by the rule that "everything affects everything else."

I want to illustrate this method of analysis by dividing the history of American foreign policy since 1945 into defined periods of reassessment and change. These different periods of postwar history can be interpreted in terms of the changing effects of the three important forces I have discussed: science and technology; the break-up of the colonial empires; and U.S.-Soviet relations. At the same time, the scheme provides the apparatus to ask questions about the goals and major instruments of foreign policy during these periods and about the political setting, both international and domestic, within which decisions have to be made.

In essence I want to postulate four periods of reassessment and change in American foreign policy since 1945: the period of reconstruction of the international system from 1945 to 1947; the "cold war" years from 1947 to 1962; a third period of "peaceful coexistence" between the United States and the Soviet Union which is not yet over, but is characterized in its present final stage by the efforts of our country to disengage itself from the Vietnam conflict; and lastly, a period "after Vietnam" into which we might already slowly be moving (since the boundaries between these major periods are neither fixed nor definitely-marked).

The first period, the period of the reconstruction of the international system, was notable for the establishment of the United Nations and the efforts, essentially frustrated, to settle the political problems of the second world war, principally the question of Germany and the rebuilding of Europe. Each of these major problems, as well as proposals for the internationalization of atomic energy, were dependent for success on the positive cooperation of the United States and the Soviet Union. Cooperation, however, floundered on the shoals of suspicion, fear, and insecurity.

The history of these years continues to be reviewed, rewritten and revised. A kind of official and conventional explanation emerged that attributed the lack of great-power cooperation to the aims of the Soviet Union to consolidate its national position of power and to use the political confusion of the immediate postwar years to further the cause of international communism. Many writers now view that interpretation as misleading. Some see Soviet behavior as a response to their own insecurity in the face of dreadful losses during the war, the hostility they historically felt from the West, and the fear that the United States might use its power, especially its atomic power, against them in the same way it had against Japan. Others see the situation in less extreme terms, more in terms of a series of calculations, on both sides, that were based on less than perfect information and on understandable but dangerous and unrealistic perceptions of the intentions of the other.

Whatever the interpretation, the period of reconstruction of the international system was cut short. In the. United States the transition to the next period, the period of the "cold war," took place through a reassessment of foreign policy goals and instruments. This reassessment produced the adoption of the so-called policy of "containment" and its implementation through the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, the establishment of NATO and general rearmament after the initial and brief period of partial demobilization right after the war. The theme of the "cold war" period was the "enemyship" relation between the U.S. and U.S.S.R., a relation that dominated all international politics. The nature of that relation was not constant throughout the years 1947 to 1962, however. It was shifting and changing, principally in response to the impact of science and technology on the development of weapons systems.

I want to underline these changes by dividing the "cold war" years into three phases. The first, during which the United States held a monopoly in atomic weapons, ended with the Soviet explosion of its first atomic device in 1949. This event, followed by the triumph of the communist forces on the Chinese mainland and the outbreak of the Korean war, led to an intensive arms race with massive military buildups on both sides. For the United States, too, it brought a series of new commitments through a system of regional and bilateral pacts that obligated the United States to provide military assistance, in one form or another, to nations around the periphery of communistheld lands. These commitments were made while the United States continued to hold a military superiority in the strategic balance, though no longer a monopoly over nuclear weapons. But in 1957, with the launching of the first Sputnik, the Soviet Union demonstrated a capacity to direct nuclear-headed missiles over intercontinental distances and, for the first time in its history, the United States became vulnerable to direct attack from a potential enemy based overseas.

The last years of the "cold war" were thus marked by this new state of U.S. vulnerability. The whole period seems to me to have come to a close in 1962 with the Cuban missile crisis. Before the Cuban missile crisis, the threat of nuclear war was constantly in the background, breaking closer to the surface during dangerous moments of confrontation like those that erupted over the Berlin question in the late 1950's and the early 1960'5. But in the Cuban missile crisis the threat of nuclear war was made clearly and unambiguously and everyone knew it. It was made by the United States, by a young, intelligent and knowledgeable President, not as a gesture of defiance or an act of bravado, but as a response to what he perceived to be a fundamental threat to the interests of his country and, beyond that and perhaps more important, to the precarious balance which was the only basis for peace between the great powers.

It was this nuclear confrontation in late 1962, it seems to me, that led the two major world powers to understand the interest that they, and they alone, shared in avoiding open and direct military conflict. It was this understanding - growing over the years as the burdens of the arms race became increasingly risky and costly - that produced in turn the nuclear test ban treaty in 1963, the installation of the "hot line" between Washington and Moscow, the initiation of continuing discussions on limiting the spread of nuclear weapons. It was this change in the basic relations between the United States and the Soviet Union that then brought us into the third period of postwar international politics, a period sometimes designated by the phrase "peaceful coexistence." It is characterized by continuing differences in the goals and value-structures of the two great powers, but also by an acknowledgement of their mutual interest in avoiding confrontation and conflict.

But this third period, these years of "peaceful coexistence," also needs to be seen as a series of phases. Beginning in the mid-1960's, the sense of mutual interest on the part of the U.S. and U.S.S.R. was joined by a realization of the limits of their own power. For the Soviet Union, it came with the growing rupture with Communist China, the ripples of nationalism through Eastern Europe, and the almost impossible cost of trying to support movements in the Third World. For the United States, it came with the strains within the NATO alliance, the difficulties of maintaining a position of effective influence in Latin America after Cuba and the Dominican affair and then elsewhere in the Third World, and above all else, with Vietnam.

In 1968 the United States began its disengagement from Vietnam and once the lines of this disengagement are clearer, the final phase of the third period of postwar international politics will be over. We will then begin to move into a new period: After Vietnam. Indeed, this is where we are in this scheme of historical analysis. It is at this point that we need to make choices about the goals of American foreign policy, about the instruments - diplomatic, military, economic, and cultural - that we will use to seek to achieve those goals. Our choices, moreover, will be fashioned by our interpretation of the political setting in which we find ourselves, a political setting influenced not only by forces in international relations but also by the pressures and demands of our domestic life.

There is not enough time for us to review the periods of history since World War II in any more detail than I already have. The more detailed review I must leave to you, bringing to bear your own knowledge and understanding of the events of the past twenty-five years. But let me emphasize how such a review might put us into a reasonable position to project into the future, into the fourth period of postwar history that is even now emerging out of our debate over the significance of Vietnam for American foreign policy.

It can, for example, be stated that peace and security have been long-range goals of American foreign policy since 1945. During the immediate postwar years, these goals were related to our efforts to create an effective system of collective security through the agencies of the United Nations. Yet, as I mentioned earlier, these efforts were frustrated by the lack of cooperation, whatever the reasons, between the United States and the Soviet Union. The goals of peace and security persisted, however, and took the form during the "cold war" years, the second period of postwar history, of what I call a "mid-range" policy of containment. This mid-range policy of containment was implemented by short-range responses to crises in largely military or military-supported terms; witness the Berlin airlift, the Korean conflict, the development of commitments of military assistance through regional and bilateral pacts.

These lines of policy - long-term, mid-range, and short-term - required a primacy, and thus a build-up, of the military instruments of foreign policy, not to the exclusion of other instruments, but nonetheless as primary means. This build-up was supported by the American public, however we measure that support, by public opinion polls or by the voting in Congress of ever-increasing military budgets. But as we move along into the third period of postwar history, we see the increasing questioning of the effectiveness of a mid-range goal of containment in pursuit of the long-range goals of peace and security. Its global extension becomes subject to sharp criticism with the rise of new configurations of power in Europe, both east and west, with the Sino-Soviet split, with the unfolding of the process of decolonization, and with the agonizing experience of the Vietnam war. In these terms, what we are now engaged in is not a rethinking of long-range goals but rather a reassessment of mid-range strategies to meet these goals. These strategies may well dictate a new ordering of the instruments of American foreign policy and must, in themselves, be responsive to a new evaluation of the international and domestic political settings within which decisions have to be made.

But all this is background, against which we need to analyze in greater depth two major areas of foreign policy to which I want to turn next: the quest for peace and security and development in the Third World. It is essential background, however, and it is background that hopefully provides intellectual tools with which to probe the future. It is thus an attempt to create a basis for avoiding the confusion that flows from the reality that "everything affects everything else." Perhaps, in the process of going through the exercise of systematic historical analysis, we can also have a better understanding, a more critical understanding, of the "pictures in our minds."

III

PEACE AND SECURITY

The quest for peace and security, stated as such, may sound like an abstraction, difficult to grasp, difficult to relate to the practical issues with which we have to deal. And yet is there any greater reality for our time than the need to achieve peace and security? The fact is that there are four pressing issues of foreign policy that we face at this very moment, that will shape the reality of peace and security in the future. They are, to state them simply ABM, MIRY, SALT and China.

In the coming months, the Congress will be asked to vote on appropriations bills that provide for the building of anti-ballistic missiles sites (the ABM question) and for the development of new strategic weapons with multiple warheads, i.e. multiple independent re-entry vehicles (the MIRV question). Decisions on both questions involve our relations with the Soviet Union, in the first instance. For the go-ahead for ABM and MIRV depends on what we calculate to be the requirements of continuing to deter the Soviet Union from taking actions that we deem inimical to our vital interests. The capacity of the Soviet Union to act, however, is something we can only estimate on the basis of what they themselves are doing about the ABM and MIRV (in the Soviet equivalents) and what we think their future intentions might be.

But the situation cannot be left there. The acknowledgement of mutual interest in avoiding confrontation and conflict has motivated the Soviet Union and the United States to continue to pursue discussions on arms control through the strategic arms limitation talks (the SALT question). If SALT can lead to effective agreements to control future arms development, then there may be no need to proceed with ABM and MIRV. But while SALT involves the Soviet Union and the United States, both governments have to consider a potential strategic threat, at some future and unknown date, from Communist China. The question that both are faced with is: Will any SALT agreement to stop new weapons development, either offensive (MIRV) or defensive (ABM), weaken our deterrent capability against China in the future?

These questions are certainly not abstractions. They are on our agenda now. What shall we do? Shall we proceed with ABM? with MIRV? What proposals shall we make in SALT? Shall we recognize Communist China? Shall we vote for the admission of Communist China into the United Nations? Would either of these last actions provide us with a better basis than now exists for relating to China in the future?

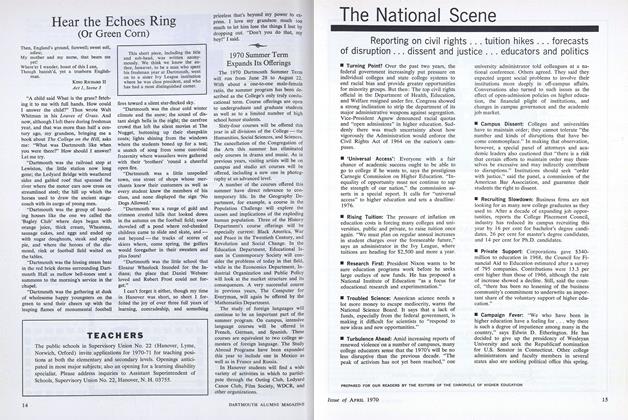

In dealing with these issues I want to try to understand how we have come to the present situation, not simply in historical terms, but in terms of a set of concepts that might be helpful in looking for answers. I thus want to suggest a simple diagram as a basis for analysis (see illustration No. 1).

The diagram sets out six basic strategic postures that the United States (or, for that matter, the Soviet Union) can adopt vis-a-vis its major nuclear competitor. These strategies run from unilateral disarmament at one end of the spectrum to preventive or preemptive war at the other. There are certainly variations of these six basic strategies and adopting one strategy at any given time does not mean giving up the chance to switch to another strategy should there be a change in critical variables. Indeed, one can say that the United States over the years has increasingly tried to develop a capacity that would give it a choice among different strategic options.

The only time when the strategy of preventive war was taken seriously in the United States was probably in the late 1940's, especially after the Soviets detonated their first atomic device in 1949. The argument for preventive war had to assume that conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States was highly probable, if not certain. But even if conflict did not break out, it could have been argued that a nuclear-equipped Soviet Union was bound, as its military power increased, to thwart the U.S. in pursuing its own goals in international politics, especially in trying to create a working international system out of the chaos of World War II.

In this context, a controlled preventive war with atomic weapons could be conceived as a less destructive conflict than might break out after the USSR was armed with its own atomic bombs and the U.S. had considerably increased its stockpiles and capacity for delivery. Moreover, even if it was possible to predict that nuclear war would not break out at some future date, it was important that the United States get about the job of rebuilding the world order. There would be an advantage in eliminating any possibility of the Soviet Union's making that task more difficult than it already was.

I need not pursue this argument any further. Let me just note that preventive war has never been adopted as a deliberate strategy by the United States or, for that matter, by the Soviet Union (insofar as I know). But this does not mean that either the United States or the Soviet Union might not decide, under certain conditions, to use nuclear weapons in what one or the other considered to be a preventive or preemptive action. The difference between a preventive war and a preemptive war is one of timing and information. One might take preventive action to eliminate an assumed graver trouble at some future date. Preemptive action is taken when you know that the other party is about to act (e.g. by mobilizing) and you want to gain the upper hand by attacking first. Both the United States and the Soviet Union are capable (in terms of military capability) of carrying out a preventive or a preemptive attack; but they no longer are as likely to do so now that retaliation is, to all intents and purposes, guaranteed. That is part of what we mean by deterrence. In 1949 the Soviet Union had no way of retaliating against the United States directly and might have been so crippled by a preventive attack as to have been gravely limited in striking at West Europe.

Preventive war remains, therefore, a possible but not a probable strategy. Nor, for that matter, is unilateral disarmament at the other end of the spectrum very likely. It is difficult to imagine that an American President would order a large, let alone complete, dismantling of American strategic forces in the uncertain world in which we live. But it may not be unreasonable to consider a move toward what would be, in effect, partial unilateral disarmament. For example, declaring a temporary halt on all deployment and development of ABM and/or MIRV could be considered partial unilateral disarmament, especially as strategic military balances have to be calculated as much on future as on existing weapons systems. Indeed, a moratorium on weapons development is frequently opposed on the basis of its being unilateral disarmament in the face of an untrustworthy opponent.

But where unilateral disarmament is urged, it is usually as an incentive to reciprocity by the Soviet Union, as a step toward multilateral disarmament. For multilateral disarmament requires reciprocal action to reduce existing military forces to agreed-upon levels. From the very early years after World War 11, one might say that American policies have favored multilateral disarmament. But American proposals, from the first proposals to internationalize control of atomic energy, have included provisions for monitoring and inspection that have been unacceptable to the Soviet Union. Conference after conference, throughout the 1950's especially, ended in an impasse on the inspection issue.

At the same time, as the Soviets struggled to gain some kind of military parity with the United States, there was little reason to expect that they would respond positively to unilateral moves by the United States toward disarmament. At least American policy-makers did not believe they would respond. But now that parity has effectively been reached, the question may not be so clear.

The strategies at the two ends of the spectrum cannot be dismissed. But developments during the years since World War II have tended to push the United States to adopt strategies toward the middle of the spectrum. During the 1950's, for example, the U.S. followed a strategy of so-called "massive retaliation." The logic was that the Soviet Union would be deterred if the United States possessed the capacity and the will to retaliate massively with nuclear weapons against any threat to its interests. Both the strength and the weakness of the strategy of massive retaliation, strangely enough, lay in its ambiguity.

The Soviets would be deterred, it was argued, by the knowledge that the United States would attack their homeland with nuclear weapons if they crossed the line (or encouraged others to cross the line) into areas of American strategic interest. But where was that line? Were the Americans themselves certain that they would be willing to order a nuclear strike at anything less than an attack on the United States itself? Even a thrust into Europe? This uncertainty was primary, especially when U.S. domination began to disappear and the Soviets developed an intercontinental capability for launching a nuclear strike of their own. The uncertainty was, at once, part of the American deterrent and a weak link in its being completely credible, most assuredly once the United States became vulnerable to direct attack.

It was the Soviet advance toward a position of military parity which led the United States to revise the strategy of massive retaliation into a more complex strategy of "flexible response," thus moving another step toward the center of the spectrum. "Massive retaliation" was not replaced by "flexible response," but now massive retaliation, as a preliminary response or through a process of escalation, became one among a number of options available in confrontation with the Soviet Union. The theory of "flexible response" provides a variety of military and diplomatic ways of initially responding to a perceived threat. It admits that nuclear confrontation might still come about through a process of escalation. But it offers multiple opportunities for compromise, settlement and withdrawal in the name of peace, and perhaps sanity, before threats of massive retaliation are deliberately invoked.

Now, the strategies of preventive and preemptive war and the varieties of deterrence that I have been talking about are based on relations between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. that essentially reflect their conflicting interests. But in my last talk I suggested that this state of "enemyship," dominating the cold war years, changed with the Cuban missile crisis. At that point relations became a complex mix of conflicting and mutual interests. And with a recognition of mutual interests, both powers moved along the spectrum of strategies to incorporate arms control into their calculations. This move, it seems to me, was made on at least three bases: first, an understanding of the limits of deterrence brought home by the experience of the Cuban missile crisis; second, by a new ability to avoid the troublesome question of international inspection by relying on national monitoring systems to detect nuclear explosions; and, third, by a desire to halt the spread of nuclear weapons in a world becoming increasingly depolarized.

What we therefore now have is a mixed strategy of graduated deterrence with arms control, through which the United States (and the Soviet Union in its own way) is seeking to pursue the goals of peace and security. It is against the requirements of this mixed strategy and these changes in international politics that we need to find answers to the questions of ABM, MIRY, SALT, and China. The argument for ABM (or one of the arguments) is that this defensive system will strengthen our deterrent capability by protecting our missiles against a first attack from advanced Soviet weapons (or future Chinese weapons). The argument for continuing the SALT talks is to try to control, by agreement, the development of new offensive weapons that would make both our defensive capacities outdated and ineffective and thus weaken deterrence on both sides.

In many respects, the problem can be seen in the mixed nature of our strategy. Both deterrence and arms control have requirements that have to be met if they are to be effective; but these requirements are not the same, and while not necessarily in conflict, they complicate each other. The requirements of deterrence, for example, can be said to be three: capability, will, and communications. You need the capability of inflicting unacceptable damage in order to deter a competitor. This capability must involve not only offensive weapons but also defensive weapons that can serve to protect your offensive capability should the competitor strike first in an effort to destroy it.

But since deterrence is essentially a psychological relation — and fails if you use your weapons - then your competitor must be convinced that you have the will to use power. This will has to be communicated to him so that he understands you and does not misjudge, or miscalculate, your intentions. Lines of communications must be kept constantly open so that each side will know when the other is providing an opening for some kind of settlement, or adjustment, so that force can be avoided.

If this process as I have just described it sounds abstract and unreal, let me remind you of what happened during the Cuban missile crisis. I do not need to trace the case in detail since I assume you have all read one or more versions of what happened. In essence, President Kennedy threatened a nuclear attack (though not necessarily immediately) against the Soviet Union unless Soviet ships carrying missiles to Cuba were stopped and ordered to return home. The American capacity to carry out the threat was never in question. The President nevertheless must have thought that his will might be doubted since Khrushchev, in their Vienna meeting the year before, had shown an arrogance and some disdain for the character of such a youthful and inexperienced man. Kennedy thus took great pains in his public announcements and in private communications to leave no doubt about the resolve of his government. He sought, moreover, to keep every possible channel of communication open so that no nuance of meaning would escape examination and no opportunity for avoiding violence lost.

Capacity, will and communications are thus the requirements of deterrence, in theory and in practice. There also are requirements of arms control that parallel these. Under arms control, there must be a willingness to limit weapons development, or to limit the use of existing weapons. These limitations can, of course, have an important effect on the weapons capacity required for deterrence. This is one of the complexities of following a mixed strategy. Which requirement is to prevail?

The will required in deterrence, moreover, is a will that could only be born of serious and prolonged differences. Yet arms control, in the abstract, requires a sense of trust, nurtured over a period. Trust, of course, does not exist between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. That is why, in the absence of trust, the United States insisted on inspection provisions to detect violations of arms control agreements. The lack of trust has thus limited arms control to areas where each superpower could, through its own national facilities, monitor the weapons tests of the other.

Capacity and will, as against limitations and trust. But in the case of both deterrence and arms control, communications is a must and here there is an interesting compatibility. In the course of arms-control discussions, it stands to reason that the two countries have to exchange a good deal of information about their weapons capacity and developments. I suspect that neither is going to give up secrets to the other. But there would seem to be no way of avoiding important disclosures and passing back and forth not only factual information, but also a sense of the general direction - if not the specifics - of strategic thinking. Arms-control discussions can, in this way, be seen as an important part of the communications network that is required by deterrence.

But perhaps I have said enough and we are ready for the question. Let us assume that we are members of the Senate and that the time has come to vote on ABM, MIRV, SALT, and China. The formal debate is over. The hearings have been held and the record is in. Undoubtedly each of us thinks there is something he has missed, that the information and the analysis he has heard have been inconclusive, that he is not sure in his own mind what is right. Many may not be ready to vote. But vote we must. And so I put the question.

Those in favor of supporting ABM? against?

Those in favor of supporting MIRV? against?

Those in favor of continuing SALT? against?

Those in favor of admitting China into the UN? against?

The vote shall be recorded.

IV

THE THIRD WORLD

For years we have had great difficulty in finding a phrase that would identify, in a collective sense, the developing nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. I use the term "the Third World" here because it is recognizable and easy, not because I consider it to be an especially valid expression of reality. For one thing, the existence of two other worlds - presumably communist and "western" - as tightly organized entities is no longer valid, if it ever was. At the same time, the nations of the Third World are themselves as diverse as one could imagine, in culture, in historical experience, in level of industrialization, in political complexity.

Yet the nations of the Third World are all, in one way or another, engaged upon the historic process of trying to make what Robert Heilbroner has called "the great ascent." And whether or not they succeed will be, with the quest for peace and security, a major issue of international politics for decades to come.

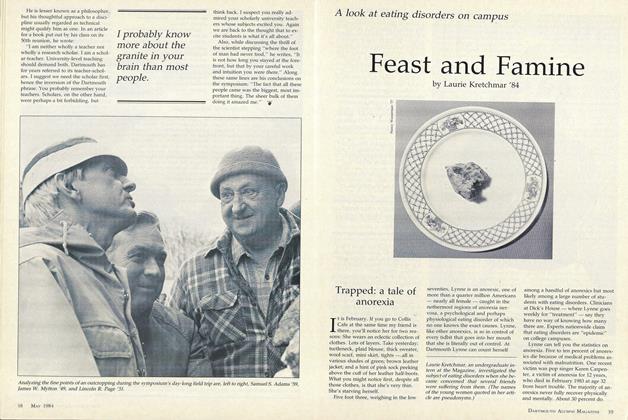

What is the "great ascent"? Heilbroner tries to illustrate what it is in the initial pages of his book under that title. It is, he suggests, as if we could imagine ourselves sitting in our own homes, surrounded by our material belongings, while one by one, each of our possessions disappears until we are left without shelter, with only worn clothes on our backs, with only one or two partially filled packages of spoiled food, without running water, without heat, without news or information about anything but the utter desolation and meanness of our own lives, isolated from the centers of decision-making in our society, unable to read, to understand, hopelessly depressed. The great ascent is the movement upwards for millions in the Third World, from that state of hopelessness and depression to something better.

There are two sets of questions we need to ask before we can look at the choices we have in our relations with the peoples of the Third World: What about our prior obligations to the poor and depressed in our own country? and what is our interest in becoming involved in the problems of the Third World? We have, in recent years, been dramatically confronted with the spectacle of poverty and hunger in America. There is no question, it seems to me, but that we cannot permit these conditions, these evils if you wish, to continue. But I am not convinced that we have, or need to have, a choice in dealing with poverty, hunger and racism at home or abroad.

For one thing, these are global conditions that in relation to the values of human dignity recognize no national boundaries. For another, there is no real evidence that the powerful resources of this country need to limit us in doing everything we can both at home and abroad. The spectacle of American affluence and indulgence is as troublesome as the spectacle of poverty and hunger. We all share, I am sure, the worry of increasing burdens of higher taxes and higher costs of living. But it is difficult to imagine that most of us would be substantially deprived if we had fewer automobiles on the highways, fewer television sets in the living room, fewer calories on our dinner tables, fewer unused toys in the children's closets, fewer cigarettes to smoke.

This is not to say that our resources, even if we allocated them in a more reasonable and sensible way, are unlimited. The tasks of combating poverty at home and abroad are enormous. The application of financial and material resources, moreover, will not do the job alone. There are complex political, psychological and sociological problems involved that will not be solved automatically through economic development. Educating, training and employing black citizens in our own country are the necessary, but not the sole, conditions for uniting what some have called a divided nation. By the same token, we now know that there is not necessarily a firm level of economic growth that will in itself propel the nations of the Third World towards the goal of effective and humane societies.

The global implications of the conditions of poverty and racism are thus reasons why we cannot make a blanket choice between working at home or abroad. And beyond these implications, there are the requirements of world integration to cope with the global effects of modern science and technology. I have already discussed these requirements. In trying to develop the bases for world order, the great ascent must be taken into account as one of the most important influences on the future shape of international politics. We must therefore participate in the great ascent ourselves since we have a stake in the integrated world order of the future. But how?

Let me begin by assuming that there will be change, social, economic and political, in the developing nations, though we cannot judge the direction of that change. Once we made the over-simplified assumption that change could, or would, take one of two directions: one that followed a communist model and one a non-communist or "democratic" model. Indeed, it was this false contrast that was frequently used to gain domestic political support for foreign aid programs. But now we hopefully know that this is a deceptive, self-deceptive, basis for acting. The roads to development are numerous and the combinations of political, economic and social organization are more complex than is suggested by any simple contrast between great power ideologies.

Let me therefore pose the question in terms of the way development in Third World countries might evolve rather than in terms of end results. And let me go further by suggesting that there is a range of possibilities - that is, that change could come about through peaceful evolution at one end of a spectrum or through imposed rule by external powers at the other. In between these two extremes there are certainly other possibilities: political change through a coup, through internal revolutionary activity, and through several forms of external pressures, from indirect economic pressure to deliberate military aggression. These might be pictured on a diagram to look like this (see illustration No. 2).

Now I should like to make several observations about this range of means of political and social change, particularly as they bear on the choices of American foreign policies. To begin with, it is important to note that the elements of violence and external intervention increase measurably as one moves from peaceful change at one end of the spectrum through coup and revolutionary activity to greater and greater degrees of external involvement. This being the case, I will suggest that to the extent that American policies affect the direction of change in Third World countries it is to our advantage that change be carried out through processes that minimize violence and external intervention. I believe there are several reasons for this, reasons that I trust become evident when we recallrecall the earlier analysis of postwar international politics.

For one thing, violence and external intervention could result, if not immediately, then at a later stage, in involvement and possible confrontation by the great powers. I realize that the scenarios that could be imagined are numerous and different. But, in one way or another, it seems to me crucial that the great powers avoid involvement that could, by escalation, bring about their confrontation and thus sow the seeds of nuclear conflict. By the same token, it seems to me that the process of decolonization and the rise of nationalism in Third World countries have contributed to a sense of independent-mindedness which resists external intervention. There is trouble for anyone who intervenes in the Third World.

In saying these things I am aware how inadequate general statements are when we are dealing with the multiple and complicated kinds of situation we find in the Third World. Intervention has a pejorative sense, but there is no way in which the United States can avoid intervention except by cutting off relations entirely. Even in the most normal and benign relations, any great power by its actions is bound to intervene in the affairs of smaller nations. We should by now understand the complexity of the processes with which we are dealing and be ready to accept the fact that there are probably no "pure" or ideal situations. By engaging ourselves in the task of the great ascent, we will of necessity intervene in the affairs of Third World countries. Our problem is to act, to the maximum possible, so that our intervention leads neitherto an increase of violence in the process of development,nor to domination by external, foreign powers (includingthe U.S.).

I am not trying to set up an unreal world. Nor do I have any illusions about the success we might have in following such general guidelines. I am only saying that these precepts seem to me to respond to the forces for world change I have tried to discuss and that we can ignore them only at our own peril. But how, you might ask, do we translate these general guidelines into specific lines of action when we have to make choices with regard to trade policies, foreign aid programs, or requests for military assistance?

To try to get at a question like this, let me develop further the three requirements for minimizing violence and external intervention that I listed in the diagram but did not discuss: capital, skill, stability. Again, I realize that I am postulating a set of conditions that we might never find, in any perfect sense, in real life. But I would contend that a Third World nation has a reasonable chance at making the great ascent if, over a long period of time, it can generate a significant amount of investment capital, can employ the requisite technological, managerial and political skills for the tasks at hand, and can maintain a tolerable level of stability so as to avoid serious disruptions to the development process from either internal or external forces.

Let me recognize one problem that stems from my incuding "internal stability" as a requirement for development. Stability can mean maintaining existing social structures and thus existing inequities and existing disparities of wealth and poverty in, for example, many Latin American countries. There is real doubt whether, in some of these countries, social change can come about through peaceful processes; controlling elites are unwilling to give up their privileges and revolutionary elites are unwilling to believe that peaceful processes mean anything but protective covering for the status quo. These realities do not, however, make less valid the need for stability in order to make the great ascent — though stability may not be possible until social inequities are eliminated. The problem for the United States is to recognize this and not act in the name of stability alone.

It is also important to point out that the provision of capital, skills, and stability were functions that were carried out, during an earlier period of history, by the colonial regimes. But they were functions carried out between unequal participants. The end objective was essentially exploitation, with the development of Third World countries only a by-product. The colonial experience was, however, the reference point from which we began to work in the years after World War II. And one of the major tasks in building up institutions of international relations since 1945 has been to provide these same attributes - capital, skills, and stability - within a new pattern of world exchange, a pattern founded on concepts of national independence and equality among nations.

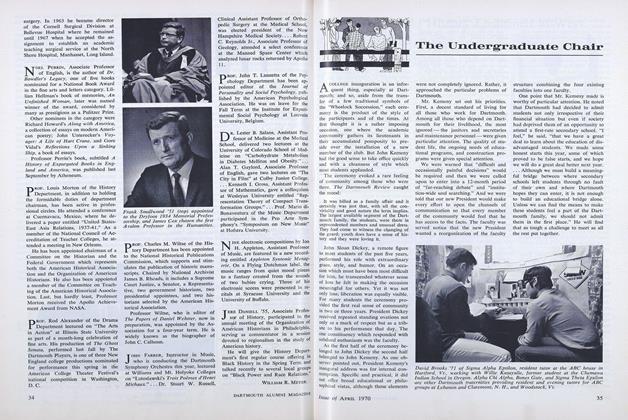

In the years since 1945 the United States has created a host of agencies to deal with developing countries. Their number and names are bewildering and, I dare say, few people except specialists have been able to keep their purposes and functions straight. At the same time, the United States has been involved in a large number of international organizations that have had similar purposes. Most of these have been affiliated in one way or another with the United Nations, though some have been regional rather than global in scope, such as the Alliance for Progress. The conceptual problem is to see all of these institutions, national, regional and global, in relation to each other and also against the requirements of peaceful change in the developing countries: capital, skills and stability (see illustration No. 3).

When these institutions are presented in relation to each other and to the functions of development, they may be more understandable, perhaps even manageable. We begin to see, for example, the variety of ways in which a country might gain foreign capital for a development project. It might gain capital through foreign earnings, through several different loan arrangements, or through a grant from a national (U.S. or other), regional or world source of investment. The diagram I have presented does not show the full picture; there is more to the international system. Most especially I have set down only the national programs of the United States. The French, the British, the Soviets, and others also have national programs that should be added, as should the programs of private institutions such as commercial banks and foundations. But the diagram is complete insofar as it presents the major choices that the government of the United States has in participating in the great ascent.

The United States, to turn the earlier problem the other way, can help a developing country gain foreign capital in at least twelve different ways (count them on the diagram). These range from the effects of its trade policies and its influence in working out world trade agreements, to loans from programs it helps fund and grants from the Agency for International Development (AID). Similarly, the United States can assist a developing country in building up the skilled manpower it needs through AID or Peace Corps programs, through the financing of regional training centers, or through supporting the work of specialized agencies of the United Nations, like UNESCO, the World Health Organization, and the Food and Agricultural Organization. In the critical and dangerous area of stability, the United States can choose (if it does wish to act) to provide military training and assistance directly or to use its influence to support regional or UN programs of arms control or peacekeeping.

I am aware that, in presenting the picture this way, I am suggesting that this variety of choices is always available to the United States as a practical matter. It may be tempting, for example, to rethink the Vietnam "case by claiming that the United States might have supported UN conciliation efforts rather than choosing to provide military training and assistance to South Vietnam in the early 1960'5. But I am not sure that other means (for example. UN mechanisms) were available or practical. The questionfor the United States may be whether or not to act, as oftenas it is how, or through what instrumentalities, to act.

Each case, each decision, has its own special configuration of forces. Without trying or even hoping to find a formula that would fit every case, I have only tried to argue that the United States should be involved in assisting Third World nations in their struggle on the great ascent. The level and balance of that assistance will be decided through the political process, and the U.S. operates within a larger international system of which it is only one part. But whatever these limits, the United States has a wide range of choices in deciding how to act. By acting, moreover, the United States will be forced to intervene into the affairs of these nations. There may be therefore a relation between the choices we make and the guidelines for intervention that I suggested earlier: that our intervention lead neither to an increase of violence in the process of development nor to domination by external, foreign powers (ourselves, as well as others).

And so we come, as we do so often, to the question of who decides such matters. I raised this question the very first time we met. I raised it with regard to questions of peace and security and asked you to test yourselves on what you would do. Now, we must raise it again. For this analysis of our involvement in the "great ascent" has again left us with choices. Perhaps by now each of you has started to make your own choices - not only about ABM, and MIRV, and recognition of China; but also about the balance between national and UN programs of economic assistance; about supporting the "soft loan" arrangements of the World Bank; about trade policies and making our own markets available to developing countries to earn foreign capital; about military assistance.

I hope you have. But whatever courage you might have mustered in confronting these issues, we still have to talk about: "Who decides?"

V

"WHO DECIDES?"

Most of you would, I trust, admit great dedication to the principles of democracy. But many of you might, at the same time, nurture a quiet doubt about the capacity of a democracy (and especially American democracy) to carry out effective foreign policies. More than a hundred years ago, De Tocqueville, that astute and prophetic observer of American life, showed a considerable amount of skepticism in this respect and his skepticism has been echoed more recently.