ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES

PROVOST Leonard Rieser has remarked how truly educational the activities initiated at Dartmouth College since May 4 have proved to be. The fact that education was not killed by these workshops, but revitalized and spurred into intensive individual reading, researching, and thinking, is testified by the following phenomena: requests from students for additional reading, demands for books on appropriate topics in the library, the fact that the bookstore continually sold out of books on U.S. foreign policy, a high degree of personal reflection (as demonstrated in discussions), and, above all, a renewed sense of community and a heightened degree of intellectual intercourse between faculty and students.

One faculty member remarked that "faculty-student interaction produced a new sense of learning among the community," and a very large number of his colleagues would endorse this statement. Most members of the community feel that the College fulfilled its function by providing the students with the opportunity to make an exciting and successful educational experience. In a more obvious and real way than ever before, people on campus were suddenly motivated to know and to act. This motivation was channeled through regular classes, through the newly instituted workshops, and through individual contacts between faculty and students.

In the context of the spring term of 1970, workshops took several forms: lecture-type talks followed by discussions, isolated seminars, or — in all cases when the interest was strong and sustained - continuing seminars. In several cases classes restructured as workshops were opened to a broader public of students, faculty, and members of the administration. A very novel fact was that many Dartmouth employees participated in these discussions. Unlike traditional classes, the workshops were all related to the pressing matters facing the nation, including educational reform, racism, repression, war, and The War. The idea behind the workshops derived its energy not from required attendance, but rather from general interest. When a question arose, a workshop was created to discuss it. A member of the class of 1970, summing up the views of a very large proportion of this class, remarked: "The high quality of questions and answers suggests that something very good is taking place here, something missing from the traditional classroom situation."

To speak of the week of May 4 as a "strike" week can be dangerously misleading, for there is little doubt that for those who seriously participated, far more learning occurred than in a normal week of classes. Indeed, that week saw the implementation of many aspects of the "Statement of Purpose" officially made by Dartmouth in its Catalogue (see p. 46 of the current issue). This statement expresses the hope that, aside from acquiring a "competence" or training in the methodology of a discipline, students will also while at Dartmouth "enlarge their awareness of, and conversance with, the world they have inherited and in which they live," and also "confront their own consciences and those of others regarding that which may be unsatisfactory and unacceptable about the way things are in their society and in the world."

Developing such a "conversance" and practicing such a "confrontation" were in fact the essential tasks of the last few weeks of the spring term at Dartmouth. Here it may be appropriate briefly to review some of the specific themes of workshops recently held on campus.

On Tuesday May 5 Prof. Louis Morton, chairman of the History Department, conducted a workshop - attended by over 200 students and faculty — on the topic "The Politics of Cambodia." Professor Morton discussed both the political and the military dimensions of the Cambodian operation, and did not find much to favor it on either count. It should be noted that different viewpoints on the validity of the Cambodian operation were to be heard at other workshops, when for example Prof. Jeffrey Hart, of the English Department, sought to justify it.

On the same first day of workshop activities a team of faculty members led by Professor of Biology Raymond W. Barratt tackled the subject of "Degradation of the Environment in Vietnam." This session began with a discussion of the geography of Vietnam and its problems of distribution and resources. The participants then dwelt on the use of defoliants in Vietnam, and examined the short-term and long-term effects of these chemicals on agriculture, food, and people. The participants felt that the workshop was highly successful from several viewpoints: (a) the information content was high and largely new to most participants; (b) the workshop drew together faculty and students from at least three divisions of the College; (c) considerable vigorous discussion resulted from the disparate modes of thinking of the participants.

One of the very first workshops, conducted by Prof. Francis W. Gramlich on the topic "Moral Issues and Present American Policy," was attended by a very large number of students who responded enthusiastically by participating in the discussion. In this session discussion centered on the specific meanings and relevance of the democratic ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity to which America is committed, and the extent to which present practices implement, distort, perhaps even contravene them. Finally, discussion turned to the issues and difficulties posed by the tension all men face between loyalty to the institutions which foster their growth and sustain their activities, and aspiration toward progressive change and betterment of these institutions in the light of traditional democratic ideals.

Another topic which attracted a large and responsive audience was the talk given by Anthropology Professor James Fernandez on "The Anthropology of War." In this workshop Professor Fernandez reached the conclusion that war is not a genetically inherited propensity, but a social invention. He explained that in primitive societies war is a limited operation, conducted within the framework of a "balanced" situation, without resulting in the obliteration of the opposite tribe or clan. He contrasted this with the modern practice of "total" warfare.

The Religion Department workshop on May 7 dealt with the broad issue of "The Religious Justification of Power." Mr. Charles Stinson indicated two polar responses to coercion and power found in the history of Christian thought (Eusebius's glorification of might and Augustine's pessimism concerning the use of power); he believed Americans today to be more Eusebian than Augustinian. Prof. Edward Yonan picked up this theme by pointing to recent treatments by Robert Bellah and others of America's historic role, a faith subject to both transcendent and demonic applications. Mr. Ronald Green spoke of the moral confusions concerning power produced by America's historic role, and suggested that Americans and American religionists have tended to vacillate between the extremes of pacifism and unchecked use of force.

Mr. Leo O. Lee, of the History Department, conducted a workshop in which he discussed writings by Chinese and Vietnamese intellectuals. Mr, Lee remarked that the way in which this spontaneous workshop developed reminded him of the pedagogical approach of perhaps the greatest teacher in Chinese history, Confucius. It is good to know that some Dartmouth students seem to have rediscovered the ancient Chinese Way.

Prof. W. H. Stockmayer of the Chemistry Department addressed himself to "The Scientist's Responsibility." Associate Professor of Education Donald Campbell was extremely active in a number of workshops and meetings. Mr. Alan Gettner of the Department of Philosophy examined the philosophical bases of democracy. In a workshop devoted to "The Responsibility of Intellectuals" I reviewed various definitions of the term "intellectual," from very general ones through culture-oriented and function-oriented definitions, to formulations characterized by a normative concern - such as Noam Chomsky's - and by insisting on the ethical dimension of the intellectual's role.

The reform of American higher education was a central topic in the discussions of May 1970 on the Dartmouth campus. One could observe the emergence of a group which calls itself the Educational Reform Group (ERG) and has undertaken a systematic review of a number of imaginative and thoughtful proposals originating from many members of the community.

Among those who predict profound changes on American campuses in the near future, Prof. Neal Oxenhandler of the Romance Languages Department stands out as a staunch advocate of the necessary cooperation between faculty and students in order to bring about important changes. He insists that the "new" teaching will express commitment of value judgments on the part of the teachers, and believes that this is especially needed in our pluralistic society where we depend on the energetic competition of competing minority views. In a workshop on "The College of the Future," he said that the "new" teaching should move away from the lecture course in the direction of new learning arrangements which bring about a joint exploration of a subject by students and teachers.

Such were some of the workshop-type activities that characterized the educational scene at Dartmouth last month. The workshops did function well, but had weaknesses. These weaknesses came from the workshops being built into the fast schedule of the May 4 week, some lasting only one hour and not repeated. Nevertheless, they did succeed in showing that the life of the intellect is related in an important way to social and political situations. Many students attended workshops on topics they had never exposed themselves to. The impressive participation in the workshops provided a living embodiment of an educational ideal often espoused but too rarely achieved: the cooperative pursuit of answers to problems that are of supreme importance to all participants. The workshops showed how exciting the educational endeavor can be, when it is based on joint concern and involvement of faculty and students. The challenge presented to Dartmouth by this experience is to capture a similar spirit of learning in its normal educational processes. That one week of searching and examination was only the beginning of an intensified motivation to learn and of a sense of community between faculty and students - two primary prerequisites for learning.

In a statement that sums up the feelings of many, Russ Lucas '70 aptly observed: "I have been here for four years and never would have believed it could happen. I am glad that I was here to experience the 'new' Dartmouth, so I will know what it is. like in the future years."

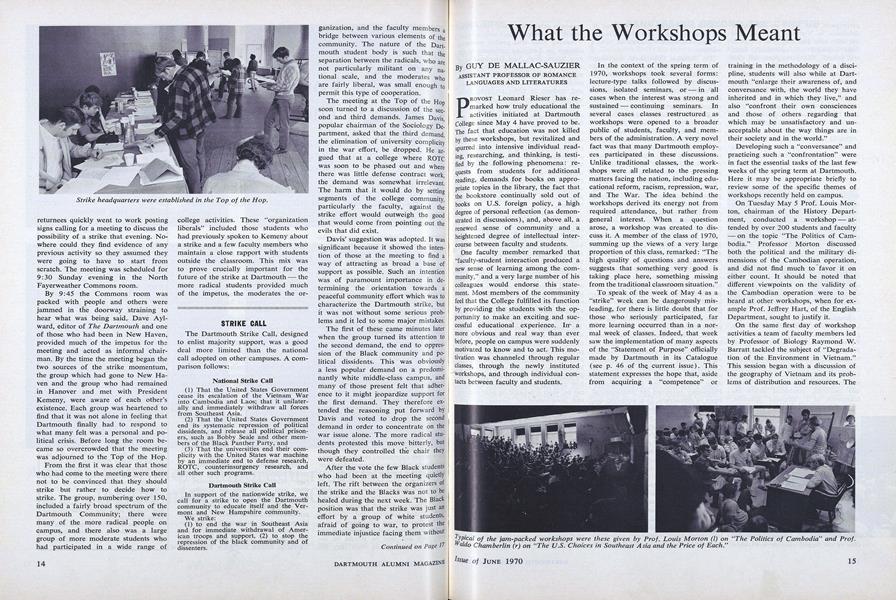

Typical of the jam-packed workshops were these given by Prof. Louis Morton (l) on "The Politics of Cambodia" and Prof.Waldo Chamberlin (r) on "The U.S. Choices in Southeast Asia and the Price of Each."

Typical of the jam-packed workshops were these given by Prof. Louis Morton (l) on "The Politics of Cambodia" and Prof.Waldo Chamberlin (r) on "The U.S. Choices in Southeast Asia and the Price of Each."

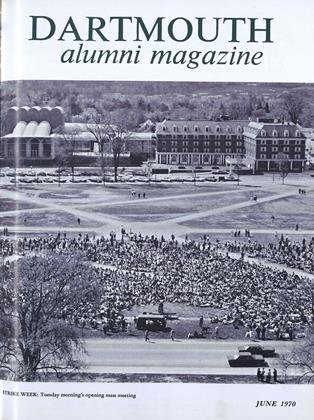

One of the largest outdoor workshops.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

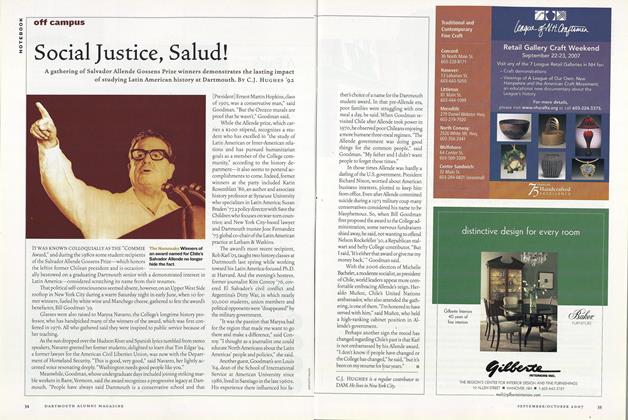

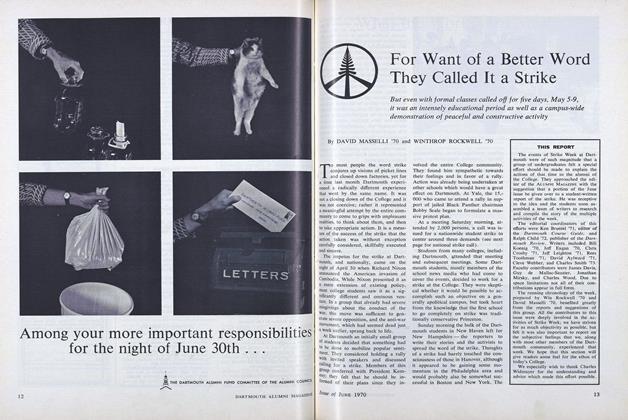

FeatureFor Want of a Better Word They Called It a Strike

June 1970 By DAVID MASSELLI '70 and WINTHROP ROCKWELL '70 -

Feature

FeatureSix Professors Reach Retirement

June 1970 -

Feature

FeatureNew Environmental Studies Program To Be Launched in the Fall

June 1970 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1970 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT KEMENY'S RADIO TALK

June 1970 -

Article

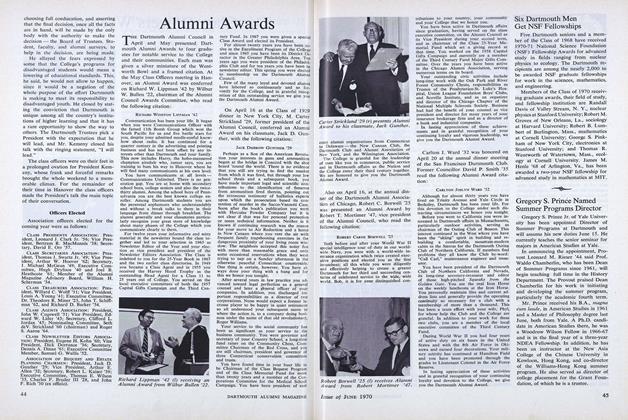

ArticleAlumni Awards

June 1970