For Want of a Better Word They Called It a Strike

JUNE 1970 DAVID MASSELLI '70 and WINTHROP ROCKWELL '70For Want of a Better Word They Called It a Strike DAVID MASSELLI '70 and WINTHROP ROCKWELL '70 JUNE 1970

But even with formal classes called off for five days, May 5-9,it was an intensely educational period as well as a campus-widedemonstration of peaceful and constructive activity

To most people the word strike conjures up visions of picket lines and closed down factories, yet for a time last month Dartmouth experienced a radically different experience that went by the same name. It was not a closing down of the College and it was not coercive; rather it represented a meaningful attempt by the entire community to come to grips with unpleasant realities, to think about them, and then to take appropriate action. It is a measure of the success of the strike that the action taken was without exception carefully considered, skillfully executed and sincere.

The impetus for the strike at Dartmouth, and nationally, came on the night of April 30 when Richard Nixon announced the American invasion of Cambodia. While Nixon presented it as a mere extension of existing policy, most college students saw it as a significantly different and ominous venture. In a group that already had severe misgivings about the conduct of the war, this move was sufficient to generate severe opposition, and the anti-war movement, which had seemed dead just a week earlier, sprang back to life.

At Dartmouth an initially small group of students decided that something had to be done to mobilize popular sentiment. They considered holding a rally With invited speakers and discussed calling for a strike. Members of this group conferred with President Kemeny; they felt that he should be informed of their plans since they involved the entire College community. They found him sympathetic towards their feelings and in favor of a rally. Action was already being undertaken at other schools which would have a great effect on Dartmouth. At Yale, the 15,000 who came to attend a rally in support of jailed Black Panther chairman Bobby Seale began to formulate a massive protest plan.

At a meeting Saturday morning, attended by 2,000 persons, a call was issued for a nationwide student strike to center around three demands (see next page for national strike call).

Students from many colleges, including Dartmouth, attended that meeting and subsequent meetings. Some Dartmouth students, mostly members of the school news media who had come to cover the events, decided to work for a strike at the College. They were skeptical whether it would be possible to accomplish such an objective on a generally apolitical campus, but took; heart from the knowledge that the first school to go completely on strike was traditionally conservative Princeton.

Sunday morning the bulk of the Dartmouth students in New Haven left for New Hampshire - the reporters to write their stories and the activists to spread the word of the strike. Thoughts of a strike had barely touched the consciousness of those in Hanover, although it appeared to be gaining some momentum in the Philadelphia area and would probably also be somewhat successful in Boston and New York. The returnees quickly went to work posting signs calling for a meeting to discuss the possibility of a strike that evening. No-where could they find evidence of any previous activity so they assumed they were going to have to start from scratch. The meeting was scheduled for 9:30 Sunday evening in the North Fayerweather Commons room.

By 9:45 the Commons room was packed with people and others were jammed in the doorway straining to hear what was being said. Dave Aylward, editor of The Dartmouth and one of those who had been in New Haven, provided much of the impetus for the meeting and acted as informal chairman. By the time the meeting began the two sources of the strike momentum, the group which had gone to New Haven and the group who had remained in Hanover and met with President Kemeny, were aware of each other's existence. Each group was heartened to find that it was not alone in feeling that Dartmouth finally had to respond to what many felt was a personal and political crisis. Before long the room became so overcrowded that the meeting was adjourned to the Top of the Hop.

From the first it was clear that those who had come to the meeting were there not to be convinced that they should strike but rather to decide how to strike. The group, numbering over 150, included a fairly broad spectrum of the Dartmouth Community; there were many of the more radical people on campus, and there also was a large group of more moderate students who had participated in a wide range of college activities. These "organization liberals" included those students who had previously spoken to Kemeny about a strike and a few faculty members who maintain a close rapport with students outside the classroom. This mix was to prove crucially important for the future of the strike at Dartmouth - the more radical students provided much of the impetus, the moderates the organization, and the faculty members a bridge between various elements of the community. The nature of the Dartmouth student body is such that the separation between the radicals, who are not particularly militant on any national scale, and the moderates who are fairly liberal, was small enough to permit this type of cooperation.

The meeting at the Top of the Hop soon turned to a discussion of the second and third demands. James Davis popular chairman of the Sociology Department, asked that the third demand the elimination of university complicity in the war effort, be dropped. He argued that at a college where ROTC was soon to be phased out and where there was little defense contract work, the demand was somewhat irrelevant. The harm that it would do by setting segments of the college community, particularly the faculty, against the strike effort would outweigh the good that would come from pointing out the evils that did exist.

Davis' suggestion was adopted. It was significant because it showed the intention of those at the meeting to find a way of attracting as broad a base of support as possible. Such an intention was of paramount importance in determining the orientation towards a peaceful community effort which was to characterize the Dartmouth strike, but it was not without some serious problems and it led to some major mistakes.

The first of these came minutes later when the group turned its attention to the second demand, the end to oppression of the Black community and political dissidents. This was obviously a less popular demand on a predominantly white middle-class campus, and many of those present felt that adherence to it might jeopardize support for the first demand. They therefore extended the reasoning put forward by Davis and voted to drop the second demand in order to concentrate on the war issue alone. The more radical students protested this move bitterly, but though they controlled the chair they were defeated.

After the vote the few Black students who had been at the meeting quietly left. The rift between the organizers of the strike and the Blacks was not to be healed during the next week. The Black position was that the strike was just an effort by a group of white students, afraid of going to war, to protest the immediate injustice facing them without looking at the problems of the whole society. They looked upon the meeting's repudiation of commitment to Black America in the name of expediency wjth utter contempt.

Shortly after this the meeting at the Top of the Hop came to a close and a self-appointed steering committee, comprised of those who expressed interest in working further that night on organization and specific plans, met in Bartlett Hall, home of a complex of educationally oriented student organizations. With Lynn Hinkle, a junior, presiding, the meeting debated the earlier vote to drop all but the first demand. Professor of Government Denis Sullivan argued that the decision at the Top of the Hop was justified because it would enable the strike to move outside the immediate Dartmouth community on an issue of wide appeal; it could, in short, be the basis of widespread political action which he thought would be impossible with the second demand conjoined. Sullivan would pursue this idea of action on the first demand and in so doing create one of the major political activities of the strike, the Continuing Presence in Washington (see page 25). But there were still deep reservations in many minds about dropping the second demand and a heated debate would take place Monday afternoon over whether the second demand should be reinstated in the Dartmouth strike call.

The group that was meeting in Bartlett concurred that it was calling for a strike "to shut Dartmouth down in order to open it up." By shutting down the institution the strike committee meant the cancelling of classes and the suspension of the normal functions of the academic community. The "shutdown" would enable the various ele- ments of the community - students, faculty, administration, staff and alumni - to "open" themselves to a discussion of the issue at hand, not only to educate themselves but hopefully to carry their concern and their sense of urgency to the community at large. The strike committee said it wanted a strike not "against" the College but a strike "by" the entire College against the actions of the Nixon administration in Southeast Asia.

It was agreed to call for a mass meeting of the college community Tuesday morning at 10:00 a.m. on the green to vote on a strike resolution. Workshops were planned and a call went out for dormitory and fraternity meetings Monday night at 10 o'clock.

The suggestion was made that a delegation go to President Kemeny's house that night to talk with him about what was being discussed and planned. At first the proposal was rejected. But it was argued that Kemeny would probably be up anyway since he has a reputation for keeping late hours; that going to his house at midnight would stress the urgency the group felt about the strike; and finally that Kemeny should have as much time as possible to consider what was being planned so that he could consider his own position in light of the direction the strike group was taking.

When approval for such a visit was won from the group, Kemeny was contacted. He was immediately receptive to such a meeting and five students left for his house at around 11:45. The students included Bill Koenig, Dave Graves, Win Rockwell, and Lynn Hinkle.

In the meeting with Kemeny the group made it clear that it had requested the meeting in order to keep him informed and asked him to consider action as President in light of the call for a strike. His questions were tough. "Once you are on strike what will you do? How long will you strike? What do we do about those who don't want to strike?" These were all questions that the five students had known they would face and for which they had only partly satisfactory answers. They told Kemeny that workshops were being organized and that a large canvassing operation in New Hampshire and Vermont was under consideration. They told him they did not know how long the strike would last but that provisions should be made for those who wanted to continue their studies. At this point the group felt themselves at the outer limit of what they reasonably could claim were the tacit instructions of the steering committee. One of the five students, emphasizing that he was going beyond the earlier discussion in the Bartlett Hall meeting, suggested that a two- to three-week strike with major effort on canvassing was a possibility. The idea was picked up and pressed by the others. The students argued that none of them had ever felt a real sense of community at Dartmouth and that a strike by a community as a community would have the potential to bring to Dartmouth a kind of unity that had long been absent. One student said to Kemeny, "When you became President we felt there was hope again that students could find meaningful leadership from their president. We don't know all the answers to your questions and we can't create alone the kind of community we envision, but if you and the faculty will join in the leadership that has already come from the students, the problems can be worked out."

In the course of the one-and-one-half hour meeting Kemeny switched from playing the devil's advocate to exploring the possibilities of the kind of strike that was being proposed. He thought through some of the problems out loud and suggestions as well as criticisms came from all quarters. Mrs. Kemeny was present and made a very strong argument to her husband that the community was facing a serious crisis and that there were times when even an institution such as Dartmouth had to break out of its traditional posture and respond.

By the time the meeting had ended Kemeny had made it clear that he was actively considering his own role in the proposed strike, although he gave no hint as to what it might be. He said he wanted to meet with the group the next day after it had met once again with the steering committee. He said he would listen at that time and decide what if any stand he would take. He had a routine monthly press conference scheduled Monday at 10:00 p.m. on WDCR, a perfect forum to speak to the whole community.

Kemeny was asked to consider calling a faculty meeting Tuesday at which the faculty could take a position on the strike. He was also asked to consider canceling a Navy recruiter who had been scheduled for May 8. It was felt that the visit of such a recruiter would be provocative to radical students at the very time when an effort was being made to unite the community. It later developed that the recruiter was properly discouraged and made the decision himself that the week of May 4 was not an appropriate time to visit Dartmouth.

When the meeting broke up at 1:15 the five students were greatly encouraged by what they had heard. They had received a reception which they had not thought likely when they had driven out to the President's house. Kemeny had seemed receptive to the concept of "closing down in order to open up." He had seemed interested in striking to "do" something.

After the group of five left Kemeny's house they discussed the meeting for a while among themselves. At approximately 3:00 a.m. they called a number of friends to the COSO room in Robinson Hall and explained what had happened in the meeting with Kemeny. The group said they were concerned that they had gone beyond the discussion of the previous evening in Bartlett by suggesting a possible time limit on the strike and by suggesting that canvassing might be an important aspect of such a strike. It was finally agreed that everyone would have to wait for the steering committee meeting Monday afternoon to see what the reaction would be to the meeting with Kemeny.

In many stages of the discussions Sunday night and in the dawning hours of Monday it became clear that those who had come forward to commit their time to a strike had no patience with symbolic protest. Everyone wanted action and they wanted it in forms that could be appealing to a wide range of backgrounds and abilities. They wanted action which could reconcile the disparate elements of the Dartmouth community and, hopefully, action which could help to reconcile the society beyond Dartmouth. Theirs was a large hope.

It was an argument which was highly irritating to some of the more radical factions on campus. They argued repeatedly during the early stages of the strike for the steering committee to forget about Kemeny and the more conservative segments of the college community: "We have a strike and we have demands and let's not get hung up about who's going to go along with us. If some people don't want to go along with us, screw 'em." It was an argument that was batted back and forth all week. The organization liberals (a descriptive term loosely applied since there were all gradations of opinion) felt that by focusing on the war issue there could be a strike, an umbrella, which would carry the whole community. They felt that, if possible, it was important to avoid alienating elements of the community so that groups under the strike umbrella, feeling strongly about issues other than the war, would be able to move out and argue their views in a community which was still willing to listen.

The radical members of the group saw the three national strike demands as deeply bound together and interrelated; Vietnam was merely oppression abroad, a different form of the oppression used at home on dissenters and Blacks; university complicity was tied up with the notion that an entire, seemingly unconscious, system supported and in fact constituted the instruments of repression. Many of the radicals felt that the sacrifices required to maintain the broad coalition were morally and tactically wrong since they could conceive of the beginnings of a solution only when all three issues in the national strike call were recognized as stemming from a common malaise. They argued that to compromise in setting up the strike was to fall into the same terrible mistake and hypocrisy that the strike was designed to protest. They forced those who tended toward expediency to face the fact that one had to make a moral decision and commitment even when it involved risk.

As the week wore on the debate in this area clearly settled into a running skirmish between those who said "what is pragmatic" and those who said "what we are morally obliged to do." In most cases each individual, regardless of the terms on which he felt the strike should be called, was committed personally to the three issues. The argument was one of tactics. Fortunately, rather than hardening as the week wore on, each side softened its position. The radicals and the moderates seemed increasingly willing to listen to each other and to take some of each other's philosophy. It was this atmosphere which allowed the event ual resolution of the debate over adoption of the second national strike demand.

As those who had worked most of the night slept late into Monday morning, a line of Ohio National Guardsmen knelt on top of a knoll at Kent State University and fired a salvo of bullets into a crowd of demonstrators. Four students died; ten were wounded. It was unclear why the troops had fired and, as President Kemeny was to say Monday evening, "the details of how they died ... are unimportant. What is important is that civilization in this country has reached the stage that I find totally intolerable." The events at Kent State Were to have an important effect on the magnitude of protest not only at Dartmouth but at other institutions across the country.

Monday morning marked the first awakenings of the political movements that would eventually carry part of the Momentum of the strike. Ralph Child, a sophomore, set to work organizing workshops to follow up Tuesday morning rally. The workshops were to serve as a particularly important element of the strike in the first four days. They provided a forum for those who wanted to speak, not only on the immediate strike issues, but on all manner of social issues as well. Some were amused that a workshop on the women's liberation movement was scheduled in Casque and Gauntlet.

In Government 50, a course on political behavior taught by Denis Sullivan, the subject of the strike was raised Monday morning. Sullivan had been in Chicago for some professional meetings when he heard Nixon's speech on Cambodia. Said Sullivan, "I felt that regardless of whether or not Nixon's action would end the war sooner, he had violated a whole set of tacit understandings necessary to a workable system of government." At that point Sullivan, who has never been politically active before and who says he hates activism, felt he had to act. He walked around Chicago on May 2 feeling "depressed as hell" and sensing the deepness of the division between many working Americans and the student demonstrators he saw near his hotel. By the time he returned to Dartmouth he had been thinking about various courses of action that might be possible. When the subject of the strike and related political action came up in class Monday, Sullivan described a course of action in which groups of people such as families and community organizations would lobby on a long-term basis in Washington. "In a rhetorical flight," said Sullivan, "I called the plan a continuing presence in Washington," the name the organization would later officially adopt (see page 25).

Before the first strike meeting David Roberts, a professor of history, and Steve Rosenthal, a junior, had discussed various forms of political action which might be taken to oppose the Nixon move into Cambodia. They had talked about a petition drive as well as a "confrontation" by delegates from colleges in New Hampshire and Vermont with the Congressional delegations in Washington. Roberts and Rosenthal were at the strike meeting Sunday night. Monday they decided that they had an opportunity to go ahead with some form of regional political action, although they were not yet sure precisely what form it would take. They checked to see if anyone on the strike committee was organizing such an effort. When they got a negative response they decided to take the initiative themselves. An eight-man committee was constituted with four students and four faculty members. It was this committee which set the stage for the major canvassing effort which developed not only at Dartmouth but at nearly forty other colleges and schools in the Vermont-New Hampshire region.

Early Monday afternoon a dispatch came over the United Press International wires stating that Communist China had declared it would support the North Vietnamese against the action in Cambodia. It was unclear what the Chinese rhetoric actually meant, but the dispatch created some uproar Monday afternoon. Copies of the story were Xeroxed and handed out to departmental chairmen who were arriving in Parkhurst Hall for a meeting with President Kemeny. Kemeny had apparently decided to test the reaction of the departmental chairmen to the ideas which had been brought to him the night before. Throughout Monday until his address to the College over WDCR at 9:00 p.m. Kemeny did not take a position. Instead he asked questions, listened carefully, and checked the attitudes of various parts of his constituency towards the proposals which by then he was considering seriously.

The steering committee meeting was set for 3 on Monday afternoon. By the time it started many attending had heard that something had happened at Kent State, but the first reports were confused.

The group which had met the previous night hoped to turn the meeting towards a discussion of their plans for a massive canvass as the major effort of the strike. It soon became obvious, however, that most of those in attendance wished to discuss the second and third national demands again. With no limitations on the membership of the steering committee, those concerned about the strike came to express their views, packing a seminar room designed for thirty with over one hundred people. Many were worried that if they did not come the strike would be taken over by a small, unrepresentative group. It was not an ungrounded fear, though members of the COSO group did sincerely try to represent the whole community.

Chairman Lynn Hinkle persuaded the meeting to put off discussion of the demands until late in the meeting and members of the COSO group began to outline possible tactics. Their plans from the previous evening were well received. Most significantly, the entire group accepted the assumptions underlying the plan: the notion of a community effort and of "opening" the College as a relevant educational institution. To minds accustomed to thinking in the rhetoric of confrontation politics, these notions would require making some great adjustments, but doing so would contribute immensely to the unique aspects of the Dartmouth strike.

One important result of this orientation was the decision to try to include College employees in all strike activities. Throughout the week, the strike committee would demand, with some degree of success, that any freedoms or opportunities allowed the students and faculty also be granted the staff (see page 27),

Many of the activities of the strike would not have been possible had it evolved into an exercise in confrontation. Without confrontation the strike was able to attract the support of an overwhelming portion of the student body. From the vantage point of Mond ay afternoon, though, no one could yet foresee the response that would develop, so when discussion finally turned back to the second and third demands their supposed political liabilities were again a major topic. Debate on this issue was heated.

This time the more radical element was not to be denied. They argued forcefully that for the steering committee to turn its back on the facts of repression in the name of political expediency would be the sheerest hypocrisy. They acted in the knowledge that their position was more idealistically defensible and out of anger at what they felt was a shortsighted betrayal the previous evening; those opposed acted out of concern for the future of the strike.

The second demand was reinstated by a wide margin. Few would later have cause to doubt the decision was a wise one, though many would learn that including it as a demand and centering major action around it were two very different things.

The issue of the third demand was not strongly pressed and the meeting soon adjourned. Some of the group stayed to arrange for the evening dorm and fraternity meetings; a small group again went to see the President.

They found Kemeny deeply affected by the news from Kent State, where by now the magnitude of the tragedy had become apparent. They held a candid session in which they stated the strike committee's opinions to him in forceful terms. They did this not to coerce, but to keep him honestly informed of what was happening.

These recurrent conversations with the President were one of the unique aspects of the strike. They were far more than an attempt by the strikers to enlist his support, though they were all politically acute enough to realize that such support was possible and that it could help them immensely. Rather the conversations stemmed from a desire to keep the channels of communication clear even during times of crisis.

Many of the strikers had been deeply affected by what they regarded as an unnecessary and harmful confrontation during the Parkhurst takeover the previous year. They felt that the unwillingness, or inability, of the administration to communicate with students during that time was one of the major causes of that event. John Kemeny had pledged to keep communications open. The strikers took him at his word and acted accordingly, even though they knew they might face charges of co-option from their own ranks.

The strikers left Kemeny's office reasonably confident that he understood their position and was somewhat sympathetic to it. They knew he had reservations about a strike, but were convinced that he would not actively oppose the plans they had outlined to him. They realized that as head of the College he had other constituencies and other responsibilities to think of in whatever he said.

They were still faced with the necessity of mobilizing a large portion of the student body. It takes only a few people to shut a university down. The strike group contained many times that number, but to close a university peacefully and then open it up again requires something approaching a consensus.

The strikers waited for Kemeny's speech and planned for the actions they would then have to take to create that peaceful consensus.

Kemeny spoke at nine that evening (see text on page 18). WDCR had been advertising the speech all day and most members of the college community tuned in to listen.

It was a memorable speech. The President did not hide behind sophistries, but clearly stated his shock at the recent events of Kent State and his personal opposition to Nixon's actions in Cambodia. He did not anywhere assign blame in a denunciatory fashion, but insisted that the entire fabric of American society needed a careful examination.

He made it clear that he felt a great duty as the leader of the Dartmouth community to aid such an appraisal, yet realized his responsibilities to those who might differ with his feelings over the issues. However, he concluded that he had seen evidence of widespread community concern over what had been happening. To provide a proper framework for expression of that concern, he had decided to suspend all classes for Tuesday, which he declared would be a day of reflection and a day of mourning for the dead at Kent State. He would allow all members of the community - students, faculty and staff - to forego normal activity for the rest of the week, if they saw fit, without incurring penalty. He urged all members of the community to participate in the discussions of the next few days.

The speech was eloquent testimony of Kemeny's concern and it set the tone for much of the next week: thoughtful, low-key and committed. Its effect on the community was sizable; its effect on the strikers was immediate.

They had to switch from arranging the strike itself to providing for a broad spectrum of strike activities, enough to accommodate nearly 4000 persons by the next day. They would have breathed a little easier if they had known of the amount of independent outside energy that had already gone into preparing such activities. As it was, they felt a little overwhelmed. They had gone from a strike organizational meeting to a full strike in a little under 24 hours.

The dorm and fraternity meetings which followed Kemeny's speech showed a great deal of support for the strike and as the strike representatives returned to Bartlett Hall to report, the enthusiasm there grew. Already the third floor was being turned into a massive publicity office that would continue to operate for the entire week.

A third steering committee meeting was held at midnight, again in the overcrowded seminar room. Attention focused on the rally the next morning. The committee which had responsibility for planning the rally announced a short line-up of speakers to precede a call for a strike vote. They felt a vote was still necessary, in spite of the President's speech, to show visible widespread community support for the activities of a strike.

Most of the speakers for the rally had already been selected, but a Black who had been asked to speak for the Black community had first accepted, then later refused. Cleve Webber, president of the Afro-American Society, was at the meeting and the rally group asked him if someone from the Black community would speak.

Webber is a special student at Dartmouth who was one of the leaders of a Chicago gang before entering the College at 24. He has a powerful presence which is aided by a soft, almost poetic speaking style that often seems to be meandering when suddenly it drives home an important point with surprising force. He patiently explained that the Blacks were frankly skeptical of the strike effort. They had their own concerns and issues and did not see how the strike thus far related to them. The whites had the additional error of asking a Black individual to speak for the Black community, rather than asking the Afro-American Society, which at Dartmouth includes all Blacks, to provide a speaker. This was why the previously contacted Black had refused.

In retrospect, Webber's speech was extremely mild, almost gentle. He could with complete justification have castigated the whites for first having dropped the second demand and, then, for trying to get a token Black to speak without making any tangible effort to relate to or include the Black community by meaningful strike activity. Instead he spoke softly and at some length, trying to explain just why the Blacks had adopted the position they took.

After Webber finished, the meeting, Which had been in session over an hour, adjourned for the moment and moved to the Top of the Hop to accommodate the large number of people trying to fill the seminar room. During the intermission, members of the COSO group decided to meet again after this meeting was over to finish planning the specifics of the rally.

The steering committee spent over an hour at the Hop debating various methods of organizing itself to provide strike leadership. Every method proposed had some serious flaw, though, and finally it was decided to maintain it as an open group of all those who wished to participate. This decision was, as one observer noted, a form of unconscious "benevolent suicide" by the steering committee with respect to fulfilling the function of providing strike leadership, but it preserved a valuable forum for discussion of the issues of the strike.

It was also doubtful whether any organized method of selecting leadership would have been effective. In a strike situation, leadership of necessity devolves to those who are taking the most effective action. For this reason, a fluid situation is superior to some fixed leadership grouping.

When the COSO group met later that night it faced much the same problem with regard to leadership. Whether they had planned it or not, its members were effectively the leadership of the strike. The group contained many of those "organizational liberals" whose skill in organizing and knowledge of the workings of the College would be necessary to insure the success of strike activities.

One member of the group, however, objected violently to the way in which the group had been operating. He was skeptical of the commitment of the members to follow through with the strike effort should it run into trouble. He also unalterably opposed its secretive nature.

These charges sparked a long and important discussion. By the end of it the members of the COSO group had thrashed out differences concerning their opinions over the way the strike should run. They had also decided to make their existence more widely known and to make a concerted effort to include persons who were connected with all major strike activities.

For the duration of the week, the COSO group which would come to be known as the strike coordinating committee, numbered about twenty persons. Though its composition shifted as time went on, it remained essentially representative of three groups: those who had been to New Haven, the group who had first spoken to Kemeny, and the organizers of various strike activities.

The meeting dragged on to dawn for the second day in a row as those present discussed the potential and philosophy of the strike which would officially begin the next day. Some of those who stayed were scheduled to give speeches at the rally at ten, but remained as long as the discussions continued.

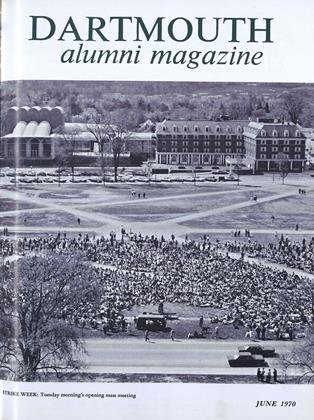

It might not have been an omen, but Tuesday was just one beautiful day. Buildings and Grounds came out early and set up a speaker's stand at the north end of the green. The rally was to start at 10 and a group began ringing the bells of Rollins Chapel ten minutes before it began. People streamed towards the green, until finally, fifteen minutes late, the rally commenced before a crowd of over 2000 who spilled over the north end of the green.

Just before Lynn Hinkle moved to call the meeting to order, a student opposing the strike came to the members of the strike group and asked to be allowed to speak. After some discussion, it was decided to let him speak first. The anti-striker may well have been the most effective spokesman for the strike group. He argued the wisdom, logistically and tactically, of Cambodia when most of those at the rally were concerned with its moral implications. In a way he symbolized the all-too-technical approach to war and killing that had angered so many of the strikers. He received little favorable reaction.

Following this, the scheduled speakers addressed the gathering. It was, for the most part, a quiet, thoughtful crowd and the speeches matched that mood. Before the strike vote was called for, three speakers discussed the rationale for such an, action.

The only thing which interrupted the smooth flow of this portion of the rally was the absence of Cleve Webber. Though he had initially agreed to address the rally, Webber evidently had second thoughts and did not appear.

Other than that, the rally progressed smoothly. When David Aylward called for a strike vote, the overwhelming majority of the crowd signified approval (later that day over 2500 undergraduates would sign the strike support petition) and the strike had officially begun.

The rally also voted in favor of a strike of indefinite duration and another mass rally before Sunday to consider its future.

The final speaker of the day, David Masselli, outlined the organization of the strike. He declared that major policy decisions would be made only by mass meetings and that the steering committee would prepare the agenda for such meetings. He also explained the existence of the COSO group, which he termed a coordinating committee which would be available to help any strike activities needing supplies, space or money.

The rest of that speech consisted of a rundown of the known strike activities. After the rally was over, many people who were organizing new activities or had ideas they wished to discuss with others took the speaker's rostrum and announced their plans and meeting places to the crowd.

A student from Alabama started a trend when he called for a meeting of all Alabamans to discuss political action. By the end of the day over thirty state organizations had been formed.

The state groups also hit on the notion of contacting alumni in their home areas. By midafternoon, a slew of representatives had gone to talk to Secretary of the College, Michael McGean. He was extremely receptive to their plans and his office provided immeasurable help throughout the week.

The Student-Alumni Coordinating Committee (SACC) eventually centralized all these varying plans under the leadership of Mike Renner and Mike Hofman. By the end of the week, most Dartmouth alumni had received pers onal letters from students explaining the strike from their viewpoint, and arrangements were being made to send speakers before alumni clubs. Though the encounters between student and alumni did not always result in perfect communication and understanding, it seems that a sizable dent was made in the generation gap.

While SACC was springing to life on the green and in a meeting at Foley House, the other activities were also flooded with eager volunteers. CPW grew quickly to almost 200 members. The canvassing operation also took shape in a large meeting in Reed Hall.

At the initial canvassing meeting, disputes rose over the petitions being used and the thrust of the petitioning drive. The canvassing group was eventually convinced by members of the coordinating committee to toughen up their anti-war petition and to introduce the subject of repression and carry a petition on that issue also. The canvassing group originally hoped to send students out as quickly as possible, but later decided to hold an information session on the issues before doing so.

Both canvassing and CPW were hesitant to include the second demand, because they felt it would weaken their effort to generate serious opposition to the war. Throughout the strike, the way in which the second demand was handled would remain a serious point of contention between the coordinating committee and the heads of activities.

In order to make the week of reflection more than a rhetorical concept, College officials decided to provide the pro - and anti-strike groups with office space and necessary materials. The strike group was given its favored COSO room, as well as space in the Top of the Hop, while Strike Back, the anti-strike group, was given a room in Carpenter Hall. The decision to provide this support stemmed not from a desire to enter the political thickets, but from a recognition that in order to profit fully from the educational possibilities of the coming week such support was necessary.

While all these organizational arrangements were being made, the most impressive event of the first day was taking place in the workshops. The iconoclastic Jonathon Mirsky (see page 26), Professor of Chinese, and Senior Fellow Steve Stonefield conducted a seminar on Cambodia. Attendance had been excellent at the earlier workshops, but no one was quite prepared for the size of the turnout here - a solid wall of over one thousand stretching from the steps of the museum through the front courtyard of the Hop and on towards the Inn, with many spilling out into the streets.

They stayed for over two hours as Mirsky and Stonefield presented a masterful introduction to the problem and then defended and expanded their views through a lively question and answer session. The most striking aspect of the affair was the diversity of the audience: students of all types, townspeople, College officials, and employees.

Mirsky is one of the finest teachers at Dartmouth and he was never more in his element than during that seminar. Stonefield, who has a distinctly different style, was also very impressive. It was a meaningful and intense intellectual experience for those who attended; to those who wondered what possible educational merit strike week could have, it provided an early and convincing example.

A short time later, the first canvassing meeting was held with nearly as large an audience in attendance. Throughout the week, workshops would be well attended and lively.

One serious problem did arise that day, It concerned the college staff. Though Kemeny had guaranteed them freedom to participate in the day's events, or just to leave if they so desired, their immediate supervisors were doing everything possible to thwart such behavior. When students offered to take over jobs in Thayer Hall, they were told that there was no need to do so, because none of the help wished to leave. It appears that the workers were told that they couldn't leave because no students were willing to fill in for them. Though this particular problem was solved, the question of the treatment of the staff was one of the more troubling of the week (see page 27).

On Tuesday evening the faculty met. It was an unprecedented event for the President had summoned to a joint meeting for the first time the four faculties: Arts and Sciences, Thayer, Tuck, and the Medical School. Such a communal body has no official existence (though one of John Kemeny's fondest wishes is that a unified faculty be established in the near future) so the meeting was billed as an informal one for the purposes of discussion. The attendance was incredibly high, higher even than that for last spring's important faculty meetings during the Parkhurst crisis.

It was also unprecedented in that for the first time some students were permitted to attend. The students could not help being happy with what they observed that evening. They were prepared to hear their actions strongly opposed; instead they found their efforts heaped with praise and heard words of support.

It is obvious that many faculty members, besides sharing the same personal convictions as the strikers, were impressed with the openness and positive nature of the strike. In contrast to the Parkhurst incident, this action was completely different: the campus remained open, there was a growing community spirit, communication among various factions remained good, the strike leaders were both levelheaded and committed at the same time. With campus after campus being plunged into violence, the peaceful revolution at Dartmouth was not the sort of thing that could be repudiated.

The only action taken by the meeting was a resolution that efforts would be made to provide for the needs of both striking and non-striking students. The Kemeny statement did not end classes for the week; it freed both students and faculty from the necessity of attending if they so chose. It was decided that the Faculty of Arts and Sciences would meet at the President's call sometime before Sunday evening.

The strikers left the faculty meeting encouraged by what they had heard. They realized that they faced a dual task in the days ahead: making the activity of the next few days as meaningful and impressive as they could and, at the same time, laying a solid base for a long-range program. It was an exciting moment. In the words of the strike newsletter, it was a time to "seize the time" and make use of it to protest the war and repression.

At a meeting in the COSO room that evening, Jonathan Brownall, a young attorney from Montpelier who teaches in one of the special interdisciplinary courses known as "college courses," offered an appraisal of the faculty mood. He felt they were looking to the students for leadership in this instance and that it was therefore important that these students come up with a convincing plan for extending the strike as soon as possible. The students agreed. They were pleased with their effort so far, but knew they must do more.

Bob Oates summed up the feeling of the strikers on the front page of the first newsletter when he wrote, "Yesterday we did a lot of talking . . . but today we must get behind our grand and lofty words. If we are really outraged by what the Nixon administration is doing in Indochina, if we really do deplore the fact that Blacks, Indians and other racial minorities in the nation are being suppressed every day, and if we disagree with the term "bums" that Mr. Nixon has used to describe us and are determined to make him hear this time, then today is the day to do something."

DARTMOUTH IS ON STRIKE! SEIZE THE TIME!

The strike moved into its second day with more excitement and activity than ever. Offices were set up all over the campus for the various student groups - some assigned by the College, others merely expropriated. If one knew the right students with the right master keys he could get access to almost any niche or cranny on campus. Several students set up "Radio Free McLane," a home-built dormitory transmitting station which must have been effective for all of about 500 yards. Not vital, probably not even useful, but a symbolic act of liberation which caught the spirit of the week.

By this time letters to Congressmen and letters to the 33,000 Dartmouth alumni were pouring out of Hanover at an impressive rate. The alumni office had immediately made available envelopes addressed to the 33,000 alumni, since many students wanted the chance to explain to the alumni the excitement they felt about what was happening at Dartmouth.

No one was sure of the effect of the letters to Washington, but feedback some days hence would show that the student effort to communicate directly with the alumni about what had happened at Dartmouth was appreciated by them and a significant step forward in a common appreciation of the potential that Dartmouth showed during the strike.

The Top of the Hop, which had been turned into a 24-hour-a-day gathering place and information center, also became the scene of amateur barbering efforts as long-haired students who wanted to go out canvassing decided they would be more effective with less hair. In addition to canvassing a schedule of visits to local high schools was arranged.

By Wednesday it had become clear that the uncertainty about the future of the strike needed to be resolved fairly quickly. Members of the strike coordinating committee had originally thought the momentum of the Tuesday vote would carry them through to the weekend, and that the choice between a return to classes and a continuation of the strike would not have to be made until that time. But many people were bothered by the uncertainty. Both students and faculty wanted to be able to make plans for the days immediately ahead. As a result of the pressure, private discussions in many quarters turned on Wednesday to a resolution of the strike. There were three basic alternatives: remain on strike, return to classes, or combine both in a "freedom-of-choice" plan. The third alternative was almost universally accepted as being the best during the numerous private discussions Wednesday. Under this plan students who wanted to go back to class would have the option to do so. Those who wanted to continue strike-related activity would have the option of ending their courses without penalty. This plan, it was argued, would carry through the spirit of the strike by respecting each individual's right to choose his own course of action. It was noted that never before had students, without fear of penalty, been allowed to make a choice between studying and the pursuit of political or moral commitments.

The Departments of Religion and Philosophy both endorsed the freedom-of-choice proposal, and an ad hoc gathering of students and faculty Wednesday had endorsed such a plan. With at least a proposal to work with and a feeling that action needed to come earlier than Sunday, several students arranged a meeting with Kemeny late that evening.

A meeting of the coordinating committee had been called for 7 p.m. Wednesday to hammer out a long range proposal for the strike. General approval was quickly obtained for the freedom-of-choice plan and the meeting moved on to the subject of Green Key weekend. It was agreed that the coordinating committee would contract directly with The Youngbloods, a rock music group, for an open concert in Leverone. The Youngbloods had originally been contracted by the Hop for a concert in Spaulding.

As another meeting of the coordinating committee began at 11 in the COSO room, five students, Chico Di Pretoro, Ken Bruntel, Win Rockwell, Tom Peisch and Chris Crosby, left for the meeting with Kemeny. The President himself had just returned from an appearance before the Dartmouth Alumni Club of New Hampshire in Concord. The Concord appearance had been Kemeny's first before an alumni group since the strike started and so it was regarded as a more or less crucial indicator of how the alumni would respond to the Dartmouth strike. Although Bill Koenig, who spoke prior to Kemeny at the meeting, was given a rough time by some of the alumni, Kemeny impressed upon them in his usual reasoned style that Dartmouth had engaged in a unique, non-violent, community effort. There were many alumni who listened and disagreed with the motivation of those who had acted, but they were almost universally impressed by the style in which Dartmouth had acted. A member of the College development office who had been at the gathering said he came away from Concord believing that Dartmouh alumni relations had become a completely new ballgame. "We will have more people really enthusiastic about what we are doing here," he said, "but we will also alienate more people."

After a personally successful evening in Concord, Kemeny was expansive although quite tired when the five students arrived around 11:45. Mrs. Kemeny offered brandy, coffee and cake to the five, but they elected only the coffee and cake fearing they might pass out on the Kemeny's living room rug if they drank anything, in their state of exhaustion. The students explained that they had wanted to talk to Kemeny that evening for several reasons. First, that action needed to be taken more quickly than had been previously anticipated; second, that a common theme had been emerging that day about the future of the strike; and finally, to explain some of the pressures which had been felt by the coordinating committee, particularly pressures from the left, so that Kemeny might better judge the mood of the campus over which he was presiding.

After a fairly long period of general discussion and two rounds of coffee, Kemeny moved the discussion in the direction of a more specific consideration of what to do next. It was agreed that the coordinating committee would try to meet Thursday afternoon, with a mass meeting to follow later that evening when a reading of student sentiment towards the strike could be taken. It was suggested that Kemeny call a faculty meeting for Friday morning so that the whole issue could be cleared up on Friday.

Kemeny seemed to think that most of these proposals were reasonable. He offered criticism and suggestions as the discussion progressed. By the time the meeting broke up, an informal timetable had been worked out for moving the decision-making process along with some speed. The conversation had been especially productive and relaxed since this had been the third meeting in three days and the students were getting to know Kemeny better. In the course of the meeting, Kemeny agreed to speak Friday night at the Youngblood concert.

Arriving back at Bartlett Hall around 1:30 several members of the group ran into Guy Brandenburg, a junior, and told him about the meeting with Kemeny. Jeff Leighton, editor of the strike newsletter, was in the room as the discussion took place and asked if he should announce anything in the newsletter. At that point Brandenburg objected, probably wisely, to the scheduling of a mass meeting Thursday evening. He argued for a steering committee meeting Thursday evening and the rally Friday morning. His reasoning was accepted and a note was sent out to Kemeny's house advising him of the changes and recommending that the faculty meeting be shoved back to Friday afternoon.

Those who considered themselves members of the amorphous body known as the coordinating committee found during the week that the bulk of the students were not willing to acknowledge a set leadership in the strike. Yet those in the coordinating committee found that an informal leadership could be defined and that decisions could be made if several guidelines were followed. First, any decision had to reflect fairly carefully the sense of direction and style which came out of the larger meetings. This job was complicated by the fact that the large meetings often left one with a series of conflicting impressions. Second, the group making the decision had to be completely honest about what it was doing and why it was acting as a decision-making group. Finally, the decision-making group had to realize that if they made a serious mistake either in reading the mood of the campus or in going beyond what they knew to be acceptable to the campus, their ability to act would vanish.

By Thursday Green Key dates were beginning to show up, not in the usual conspicuous way on the green but behind typewriters, answering telephones and performing the numerous jobs that keep an effort such as the strike going. A daycare center was established to take some of the strain off activist mothers. It was located, of all places, in the faculty lounge of the Hopkins Center. Thursday also saw the second edition of the strike newsletter which began, "As the new Dartmouth College begins its Third Day the reasons for its existence are more obvious than ever. . . . Here at Dartmouth the work has begun with a dedication and enthusiasm that is astounding to anyone who can find a minute to reflect." Some 30 workshops were scheduled for Thursday as well as 25 meetings for the state lobbying groups.

Thursday had been set aside as a day to focus attention on the Black community. A fast in Thayer Hall to raise money for the Roxbury children's breakfast program operated by the Black Panther Party netted several hundred dollars. A workshop in Webster Hall drew over 1200 students to a session that was brutally frank. The point was made, as it had been made all week, that no white could ever know his own thinking as clearly as a Black because no white lived under the kind of pressure Blacks had known since they were born. Until you go home to face a situation where your neighbors are dying hourly, the Blacks told the white audience, you will never make the kind of final decisions and commitments that we are forced to make. Throughout the week the Blacks looked for signs of sustained, long-lasting commitment from the white community towards the Black community. They never saw any such commitment and it was that lack of commitment which they defined as the racism of the institution.

During the afternoon Thursday the Committee on Organization and Policy met in order to propose a plan for Friday's faculty meeting. The proposal that emerged from their meeting adopted the freedom-of-choice framework that had been widely discussed.

That evening the steering committee met in Alumni Hall to arrange for the rally the . next morning on the green. In the course of the meeting there was a proposal to endorse a suggestion that had been made in one of the Black workshops that afternoon. Wally Ford had asked that the College donate $10,000 to the Panther Defense Fund. After some debate there was overwhelming approval on the part of the 200 or more people in Alumni Hall to commit themselves to raising the money. The committee formed to carry out the plan came to be known as the Committee for a White Commitment.

Friday morning an editorial in the Manchester Union Leader announced that Dartmouth had "bought another lemon for president" and had "gone from bad to worse."

The rally that morning was low key. Some 1500 persons sat quietly on the green as numerous speakers outlined strike activities. Two overwhelming votes approved first the intention to continue the strike and second the desire that workers be accorded the same rights as students and faculty during the strike.

By now there was little doubt that the freedom-of-choice plan would be adopted in the faculty meeting Friday afternoon. And in fact that is what happened. In his first formal meeting with the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, President Kemeny handled the chair with finesse as the faculty passed the COP resolution, with a number of modifications, allowing the students to make their own decision about the way they would spend the rest of the term.

Strike week ended on an almost perfect note. Several thousand students, dates and townspeople carried blankets down to Leverone Field House, spread them out on the huge dirt floor and waited to hear President Kemeny speak. Kemeny climbed up on the platform cluttered with all the electronic paraphernalia of a large rock band and stood before a lone mike as a standing ovation resounded throughout the immense building. He told the students that he was proud of them. He told them how he thought that they had created a truly unique week and that now they deserved to have an evening of relaxation. Then he pulled a lemon from his jacket pocket, and holding it up for the audience to see, he said,

There was one thing in the article which truly disturbed me. Of all the things that could have been singled out for that particular newspaper to attack, I would certainly have thought that the fact that thousands of students and faculty are going out in an orderly manner to try to change people's minds to affect effective political action might have been a target to attack, because that newspaper should be worried about this.

With that Kemeny said he had something he wanted the group to have. He threw the lemon out into the crowd and left the platform. A thunderous standing ovation ensued and the normally undemonstrative Kemeny was seen to give two short waves to the watching crowd as he made his way across the dirt floor to the exit. Only when he and his wife Jean had completely left the field house did the applause finally die down.

The rest of the night was spent dancing and responding not only to the music of the Youngbloods but to the excitement which everyone finally felt about Dartmouth.

BY Monday morning much of the campus had retreated to a semblance of normalcy. Few people could maintain indefinitely the pace that had been set the week before. Much of the weekend had been spent in sleeping off the exhaustion of the previous six days.

Under the plan adopted by the faculty most professors resumed teaching their courses. Some students chose to return to all of their classes and complete them in the traditional fashion. But many did not go back to business as usual. Instead they took advantage of various provisions of the faculty resolution to free their time so they could continue working on strike-related activities. Some took advantage of option two of the faculty plan which granted them credit in courses they had been taking. Others chose to use option three of the faculty plan which allowed them to take until December 31, 1970 to complete their courses for credit. Still others mixed all three options together (e.g. drop one course for credit, finish one course on schedule, and finish the third one next fall).

While most students stayed on campus, others went home to talk to alumni groups or work with local organizations on the anti-war effort. Some just went home. As Strike Week receded in time there were those who said that granting the students such freedom to choose had been wrong. It was said that some students had abused the freedom, and undoubtedly in some cases that was true. But to judge what action was meaningful and what was not is a risky business. Dartmouth Provost Leonard Rieser once described Dartmouth as a place where a student came to grow, not only academically but personally. Rieser said he thought it was a function of the institution to provide some shelter from the outside world to enable the growth and maturation process to take place. At Dartmouth with its peaceful Strike Week the shelter was maintained.

The week served as a focus for intellectual and personal growth. Each person was asked to make a choice about what action he would take. He had to justify that choice to himself for he had no one else to answer to. The learning process was briefly taken out of the classroom. Few would regret the classes that had been missed; many would long remember what they had seen and heard that week, whether or not they agreed with the motivation of the strike.

As the strike effort perceptibly waned in the second and third weeks, many of the original strike leaders would question the value of the entire activity. They were, understandably, distressed over the fact that many aspects of the strike had not been nearly as successful as they hoped, the inclusion of workers in activities for example.

This question of the ultimate value of the strike will probably be debated at the College for a considerable period of time. Those who did not support the two demands may well feel unhappy that so much of the energy of the College was turned towards a week of action based on them; some of those who did support the demands will feel that not enough was done.

The strike was an extremely massive, varied and complex effort. It seems that any reasonable appraisal will have to deal with it in three different contexts and judge its value by how well it succeeded in each of them. The strike was part of a nationwide movement, and as such one must examine both the effects of that movement and the way in which the Dartmouth effort fit into and aided that movement. It was a week of intensive activity and that activity and its effects on those who participated must also be dealt with. Lastly, the strike marked an attempt to lay a solid base for some significant changes in the Dartmouth community; the actions already taken to implement these changes and their prospects for future success must be evaluated.

As a nationwide effort, the effects of the strike are still a matter of conjecture. President Nixon has been put on the defensive and Congress has been given some incentive to act. What will come of this is not yet certain.

The strike galvanized the moribund anti-war apparatus back into action and gave it some momentum for the November elections. Many of the nation's schools have rearranged their schedules so that students will have time off this fall to work on political campaigns. The strike also spawned a host of lobbying organizations of which Dartmouth's CPW is a prominent example.

The Dartmouth strike made a more than adequate showing in building political opposition to the war. Both the canvassing operation and CPW have helped to mobilize anti-war sentiment in the Upper Valley and make that sentiment known to the politicians.

The national effort and that at Dartmouth have been far less successful in acting on the second demand, the end of the repression of Blacks and dissenters. In a way, this is only to be expected. The war is a discrete and highly visible venture against which opposition may be easily mobilized; racism deeply permeates the fabric of this nation, is often difficult to distinctly identify, and is not amenable to the same sort of easy solution as is the war (we could simply decide to end the war, give the proper orders and it would be done; it would be a symptom eradicated. This is not the case with a societal problem such as racism).

The third demand, as noted earlier, played little part in the Dartmouth strike. However, as shall be discussed below, the strikers were very concerned with the nature of the academic community and its role in society.

The events Of the strike week itself may be more easily evaluated. It was, for most of the student body and hopefully for other members of the community, a memorable educational experience. The content of that experience consisted not in the traditional sort of

learning but in examining a crisis situation and deciding what one's proper response to it should be. In this it transcended the normal educational process which only gives one the tools and leaves open the question of how they should be used.

Too often that traditional process is perverted or rendered meaningless, because the problem of action is never consciously faced and resolved. The spirit of the strike impelled participants to essay this sort of self-examination. This is not to say that everyone went through intense soul searching during the strike or even that deep introspection is a prerequisite for taking proper actions, but only that the strike, in its workshops and discussions, in its publications and rallies stressed the necessity of individual examination of the relation between knowledge and action.

Other valuable aspects of strike week centered around its community nature. A college got to see its new president in action and liked what it saw; faculty saw students taking the lead in expressing their personal commitments and creating from them a new educational experience; students went out to meet the people of the Upper Valley, teaching and learning at the same time.

As for the future, here again one can only make conjecture. The way in which the student body makes use of the academic freedom granted it this term by the faculty may well determine the direction that educational reform will take at the College in the years to come. If, freed from the tyranny of grades and requirements, students demonstrate that they can meet the challenge of traditional education while engaging in meaningful activity outside that structure, major revisions of curriculum and grading may result.

There are many other areas in which change may come as a result of the strike: student-alumni relations, the treatment of workers by the College, relations between Blacks and whites on campus. Efforts in all these areas are just beginning. They were nurtured in the peaceful and reflective atmosphere of the strike. Hopefully, the spirit of those days will continue and significant progress will be made in creating a new Dartmouth.

Strike headquarters were established in the Top of the Hop.

No dearth of strike notices.

Quarterback Bill Koenig '70 supportingthe strike call at Tuesday's big rally.

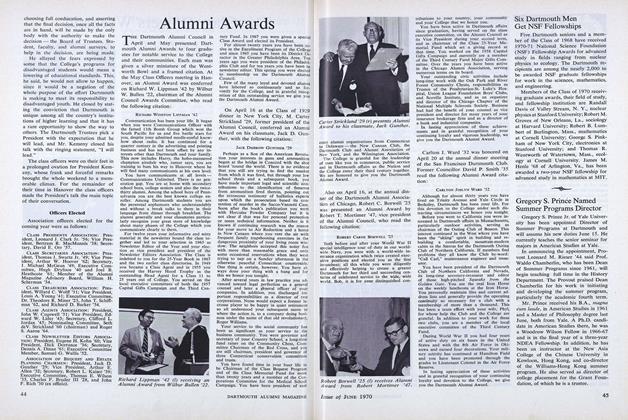

On behalf of faculty and administrative colleagues, Prof. Thomas B. Roos of theBiological Sciences Department, presents President Kemeny with a lemon tree,instigated by the Manchester Union's editorial, anent the strike, that Dartmouthhad acquired another presidential lemon.

© Copyright 1970, Rockwell and Masselli

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSix Professors Reach Retirement

June 1970 -

Feature

FeatureNew Environmental Studies Program To Be Launched in the Fall

June 1970 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1970 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT KEMENY'S RADIO TALK

June 1970 -

Article

ArticleWhat the Workshops Meant

June 1970 By GUY DE MALLAC-SAUZIER -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards

June 1970

Features

-

Feature

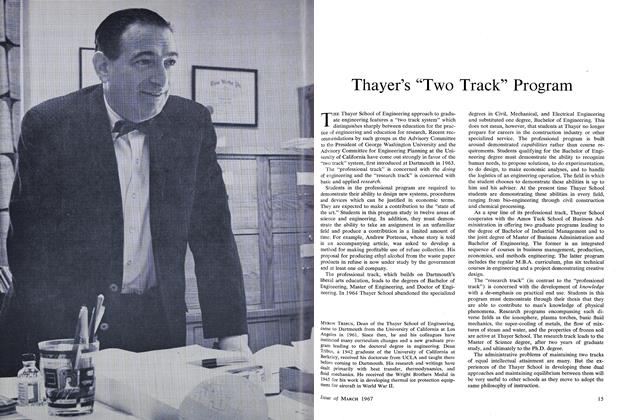

FeatureThayer's Two Track Program

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureADRIAN W.B. RANDOLPH

Sept/Oct 2010 -

FEATURE

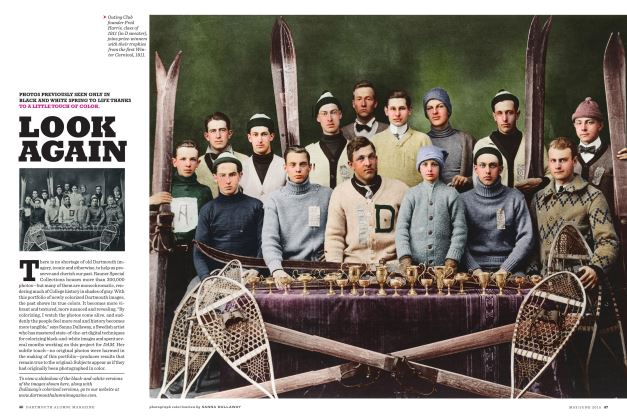

FEATURELook Again

MAY | JUNE -

Feature

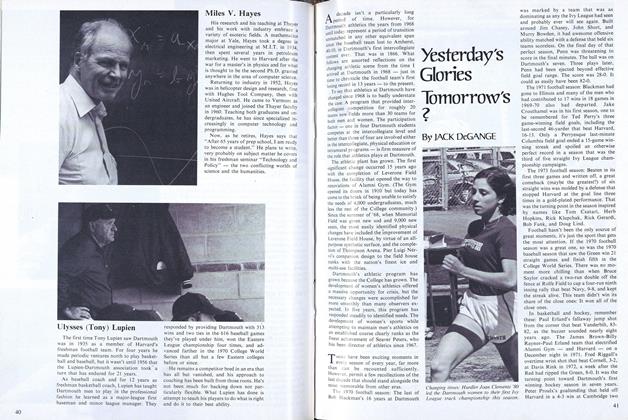

FeatureYesterday's Glories Tomorrow's ?

JUNE 1977 By JACK DeGANGE -

FEATURE

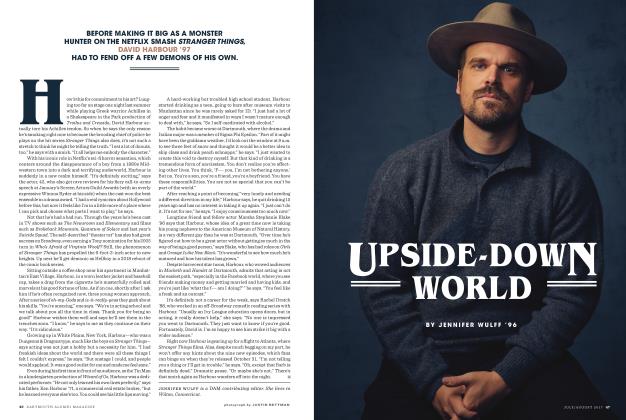

FEATUREUpside-Down World

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Past Is Prologue

JULY 1963 By T. DONALD CUNNINGHAM '13