To remedy the teacher shortage many are urging higher pay, but few are pointing out

M.A. '35, PRESIDENT OF HOOD COLLEGE

IN all the current discussion about the acute shortage of teachers, no one seems to be raising his voice to express die perennial truth: BUT great teachers do not teach for money! It appears to be assumed that if, for the first time in the memory of men now living, the teacher is in short supply and will become even scarcer, it follows that the supply of teachers will be increased if their salaries are made commensurate with that of other professions.

That this assumption is partially correct, everyone would agree. In a pecuniary economy, when the demand for teachers will skyrocket in the next ten years with no prospect of a supply adequate to the demand, there can be no doubt that teachers will receive monetary rewards more in keeping with other professions. But it will be a sad day for the teaching profession if the primary consideration in the mind of the individual teacher becomes that of money reward and not what, for lack of a better term, we might label the "calling." The genuine satisfactions enjoyed by the teacher in our society have come not from material rewards but in spite of the lack of such compensations.

After 23 years of teaching, I elected to experiment with life on the other side of the academic fence - the administration. And it has been fun to be associated with that group I had formerly thought of - not always in wholly complimentary terms - as "The Ad Building." I can enter into complete sympathy with a faculty member who comes to my office to tell me that his salary is not sufficient to cover his annual expenditures. I can truthfully say that in twenty years of teaching at Dartmouth, there was no year when I did not have to earn supplementary income to balance the family budget.

But I can say this without any bitterness or complaint against Dartmouth since I remained there for those twenty years because I wanted to do so, and in spite of the fact that more attractive financial offers came from other institutions. I entered teaching because I wanted that kind of life and not for the financial rewards. On being graduated from college, a very close friend of mine advised me strongly to study law and assured me that in five years after law school he could secure me a judgeship. (And he happened to be in a political position to do just that!) But I wanted to teach. Perhaps one reason for this was that frequently expressed by a former colleague, Dr. McQuilkin DeGrange, who said: "In what other job can a fellow do just what he likes to do and get paid for it?"

At the time of the completion of my doctorate at Columbia University in 1928, teaching positions must have been relatively abundant for I had my choice of three jobs. Among these three positions there was a spread of $1,000 difference, and the least attractive was that of Dartmouth. Why, with a wife and a child, I did not take the best-paying one is a mystery only to those who cannot understand the mentality of a teacher. To be sure, a part of the responsibility for this decision must rest with that great teacher and scholar, Dr. Franklin Henry Giddings, who advised me to take the Dartmouth job. But only my wife and I were responsible for the decision made in each of those first five years at Dartmouth when we declined offers of jobs at other institutions at a substantial increase in salary.

I wanted to teach and I wanted to teach at Dartmouth. Why such considerations outweighed the importance of monetary rewards, only the perspective of the years has given me partial answers, and these are not solely rationalizations. To begin with, the administration of Dartmouth was so enlightened that we faculty members had confidence that our pursuit of the truth, wherever it might lead, would meet with the staunchest support from the President. This dedication to the principles of academic freedom provided a climate in which it was a joy to work. Likewise, the President felt that a good faculty member should also be a good citizen and participate in civic affairs. This led, in my case, to a most rewarding experience in town government. In the next place, the students were a highly selected group of young men and, with very few exceptions, if they were treated with the respect due them as persons, one received their respect in return. Finally, the emphasis of the institution was on teaching and not on research. Consequently, my associations were with colleagues whose primary objective was teaching rather than spending the best working hours of the day on research and then, in utter weariness, meeting classes.

However important all these factors were, perhaps they yield in significance to a still greater satisfaction in college teaching, and that comes from the feeling that one is constantly growing and in the process becoming a more effective guide to those who are younger in years, in experience and in knowledge. It is a shameful confession to make but in these eight years of administration, so burdensome is the daily routine of activities that one's intellectual capital is expended without adequate replacement. Perhaps there is no college president in the country who does not yearn for more time in his study, more opportunity to replenish his intellectual reserves.

The Cassandras of our time are bemoaning the fact that the day of the dedicated teacher is past. I for one simply do not, or will not, believe it. Naturally I can speak only for the college teacher, but I firmly believe that the satisfactions of teaching will continue to make the teacher quite indifferent to material rewards. Of the truly great teachers who have influenced my life, one could have achieved great success as an engineer, another could have become an outstanding actor, still another a great lawyer. But they elected to teach!

Let us do everything in our power to get the kind of social recognition for the teacher that will result in his receiving an adequate salary, but in the process let us not lose sight of the fact that, however little the world understands it, the effective teacher is not teaching for money.

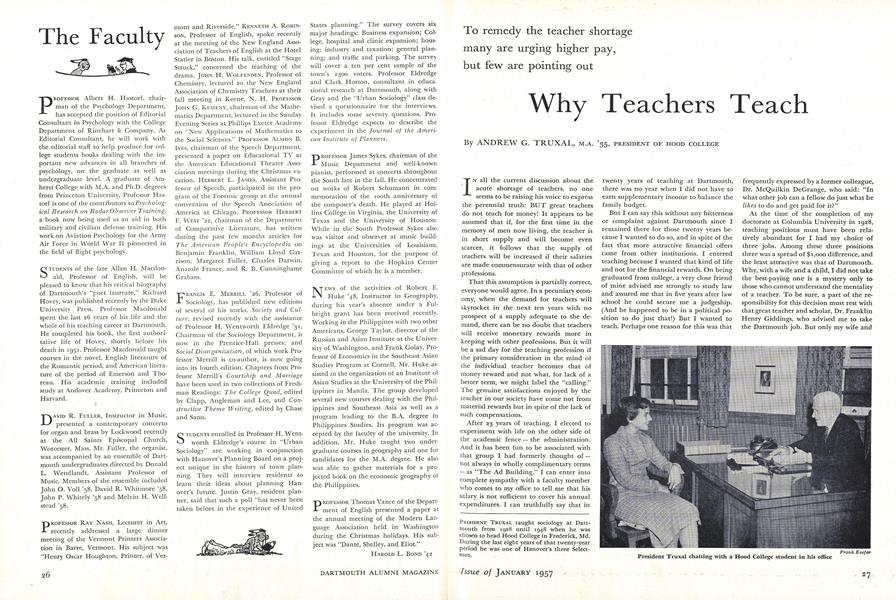

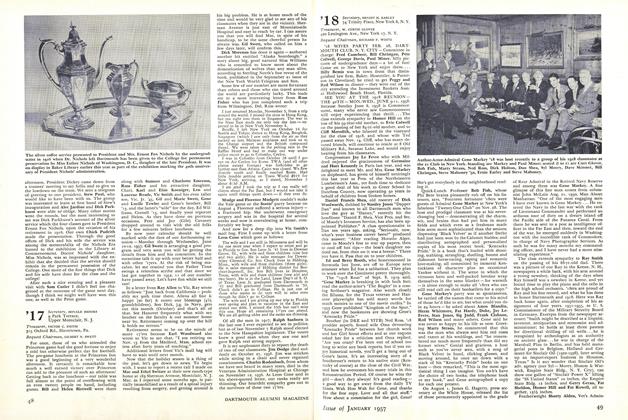

Frank Keefer President Truxal chatting with a Hood College student in his office

PRESIDENT TRUXAL taught sociology at Dartmouth from 1928 until 1948 when he was chosen to head Hood College in Frederick, Md. During the last eight years of that twenty-year period he was one of Hanover's three Selectmen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMr. President

January 1957 By JOHN L. STEELE '39 -

Feature

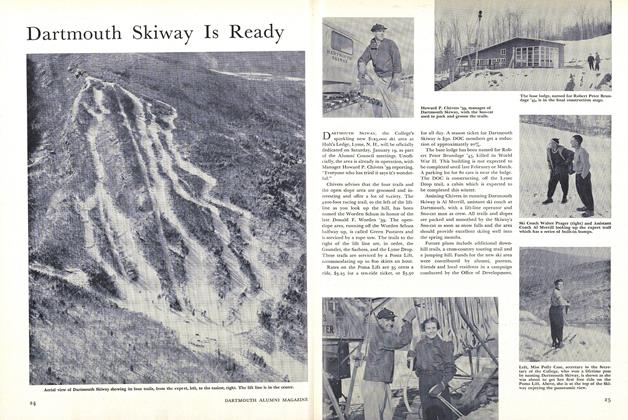

FeatureDartmouth Skiway Is Ready

January 1957 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

January 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

January 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, PETER B. EVANS, CHARLES G. ENGSTROM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

January 1957 By RICHARD C. CAHN, LT. (JG) EDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

SEPTEMBER 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Feature

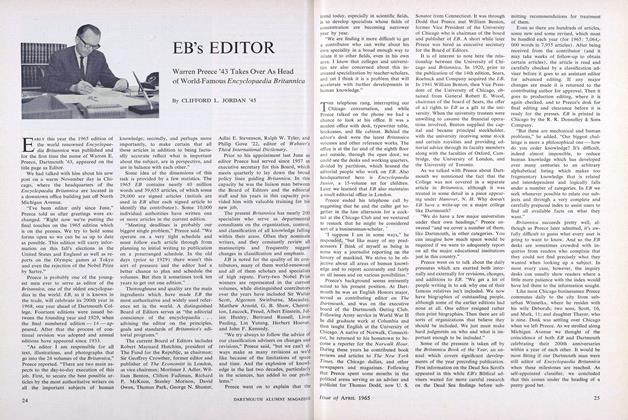

FeatureEB's EDITOR

APRIL 1965 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureHORNING: Invention of the Devil

DECEMBER 1963 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

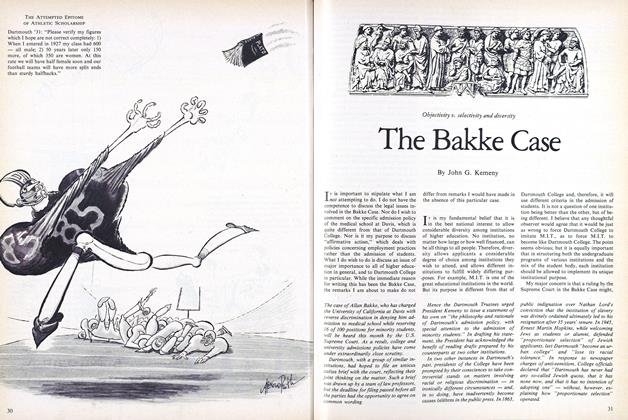

FeatureThe Bakke Case

OCT. 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

OCTOBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureStudent Workshop

MAY 1957 By VIRGIL POLING