Following are the texts of the talks given at the Convocation exercises in Webster Hall on the evening of September25, with President Kemeny presiding:

MEN AND WOMEN OF DARTMOUTH:

This is the first time in 203 years that the President of the College has so addressed the freshman class. Convocations have marked many memorable moments in the history of the College and this particular Convocation marks the beginning of a historic year. It is traditional to open the year with an address by the President and I shall fulfill that traditional obligation. But before I do so, there are three speakers who bring special greetings to entering students.

Our first speaker has major responsibility for the welfare of all undergraduate students. The Dean of the College, Carroll Brewster:

Remarks by Dean Brewster

The 13th President of Dartmouth College calls us together to mark the opening of the 203rd year of the College, to celebrate the presence among us of the men and women of the Class of 1976 and, as at no time in recent memory, to signal the rebirth of Dartmouth College.

We convene at a time when the benefits of undergraduate education are sought by more and more young Americans and the goals which seemed so clear a generation ago are less and less definite. A generation ago colleges like Dartmouth were content to educate men and women for a society presumed stable at least for the 40-year period of one's working life, for a world of employment which looked congenial to a well-rounded bachelor of arts. All that has changed. The world's need for the highly trained puts pressure on us to do more and more faster and faster to hasten the training which prepares one for a career in tomorrow's technological world.

I believe we must work together right now to resist external pressures on undergraduate education to do more and more in less and less time, pressures which now threaten the climate of individual contemplation, the serenity of life the walls of a college can provide for a short time, and solitude, "the nurse of full-grown souls." As Dartmouth bursts to life this week, I urge that we guard her treasured stillness and, as students, "far from the clank of crowds" rediscover that "there is a society in the deepest solitude" in which the vision of the leader, the scruples, judgment, courage and staying power are born, as well as a sense of mystery and the infinite and timeless in poetry, art and music, love and prayer.

Wisdom, spiritual growth, good judgment are our goals; not unbridled intelligence. "What else is wisdom," says Euripides:

"What else is wisdom? What of man's endeavor, Or God's high grace, so lovely and so great.

To stand from fear set free, to breathe and wait; To hold a hand uplifted over hate; And shall not loveliness be loved forever?"

At the same time we must quicken the heart of the true adventurer, rising to change not cringing from it, with the spirit of the self-reliant whose talents and place depend not on the transient structures of the status quo. As periods between major social change and consequent realignment of values and social goals shorten, no quality will better adorn our graduates than a zestful and willing delight to confront the unexpected. Our adventurer must understand historic values, the sinews of our culture, if he is to feel at home in change, but he must as never before be prepared for a life of constant retraining, with the resiliency and adaptability of a free and independent spirit.

We must finally put to rest the cruel deceit that educating the whole man at college need not necessarily involve excellence in scholarship, that college life and its rewards are anything but sterile when that life does not involve the greatest adventure of all, the adventure of the mind in scholarship. The world proves each day a more fearsome place to those without a proven record of achievement in that great adventure.

The rebirth of Dartmouth this year calls for a doubling of personal effort from each of us, teacher, student, staff. Year-round operation is tough.

In the past the loyalty showered on Dartmouth sprang in solemn gratitude for the willing self-sacrifice exhibited in deep and humane concern by selfless servants of this College, inspired by the example of others before them and the knowledge that Dartmouth blesses tenfold those who most generously "dare a deed" for her. Perhaps as at no time since her founding does Dartmouth now call on her every servant, every teacher, and every student to give to her of your very heart and spirit that she may be happily reborn. The loyalty she now requires depends on the humanity and respect with which Dartmouth treats all individuals, and Dartmouth is nothing but you. The respect and kindness with which Dartmouth treats one student, one teacher, affects how everyone feels about her and specifically how willing he is to give of himself in loyalty to Dartmouth. The sense of place—what one student described to me as the sudden realization that every building, every tree and every blade of grass at Dartmouth were his forever, "miraculously builded in our hearts"—this sense of place is alone a reflection of the people who touched his life here. The transforming loyalty each of you can feel for Dartmouth is a creature only of how you, Dartmouth, treat your fellow man, the fairness of competition, the respect for privacy, the compassion and constructiveness of your criticism which signifies that each of you wants the very best for your colleague in Dartmouth. Such humanity makes possible the lively and welcome clash of opinion which is at the heart of healthy institutional change. I say avoid the current and ridiculous palliative that all disagreement can be explained by what is called a lack of communication, and imitate Melville's Jarl. "Thanks, Jarl," says Melville. "Thou wert one of those devoted fellows who wrestles hard to convince one loved of error, but failing, forthwith change their wrestling to a sympathetic hug."

Dartmouth asks of her students nothing less than the gift of four years of your lives in earnest service of her ideals, in scholarship, in sport, but most of all in humanity, friendship, fairness, and loving kindness to your fellow student and all with whom you live and work at Dartmouth. Individual humanity is the stuff of loyalty. The loyalty Dartmouth will enjoy in future years, her life's blood, depends on the selflessness with which each of you now gives yourself to her noble ideals that in the end the very name of Dartmouth "makes you rejoice that you are a human being, and at the same time tremble."

The symbols whereby we speak our loyalty in intimation of the unexpressible must be fresh. The manners and sayings, the customs and habits of another generation are at best stale and maudlin, at worst offensive. We must seek fresh symbols, even new song, as we stretch for ways of saying, "I love this College as life itself" in proclamation to ourselves and to all who hear us, our pride in Dartmouth reborn.

To the Class of 1976 I now say my final welcome. I have enjoyed greeting each of you as you entered Dartmouth last week, and from that experience I can testify to anyone who thinks shaking the hands of 177 women lightens the bone- crushing task of matriculating freshmen that the Class of 1976, women as well as men, already has the granite of New Hampshire in its muscles as well as in its brains.

My hope for each of you is that four years from now when Dean Manuel and I hand you your diplomas and in the year 2001 at your 25th reunion you will say like Kazantzakis: Whatever fell into my youthful mind was imprinted there with' such depth and received by me with such avidity that even now I never grow tired and indeed gain strength from recalling it and reliving it. I welcome you by calling you to serve your college in this hour, as thousands have before you, with all your strength and all your spirit and all your heart.

Next, speaking for the student body, the President of the Senior Class, John Hauge.

Remarks by John R. Hauge '73

I would like to talk with you tonight about the three factors which I feel make up a college education: knowledge, perspective, and commitment.

The first is knowledge. It can take many forms: facts gleaned from lectures, theories discovered in books, opinions of knowledgeable and respected individuals. These are the building blocks with which the student constructs a library, the storehouse of information from which he will be able to draw. He can go on acquiring knowledge ad infinitum, especially at a college like Dartmouth where the faculty and facilities are first-rate__my father once told me of a man who was in the Harvard graduate school system for 18 years until he was asked to pursue his studies elsewhere.

For this knowledge to be meaningful, I would suggest that two other factors must always be present. One of these is a sense of perspective, a fitting of the knowledge gained into a total framework. Only with such a comprehensive outlook can ideas be assimilated and given their proper emphasis and status. The student begins to realize that he is not expected to grasp mentally and then intuitively to understand all the knowledge he has read, seen and heard from the hundreds of courses offered at Dartmouth (most of us take 36). The student becomes more selective; he develops his own particular view, and in so doing activates his powers of judgment. These efforts to assimilate knowledge must be given some type of driving force; this impetus is called purpose and Is found in commitment to an ideal or goal. Let me speak of this third factor in a successful college education—commitment.

By the time he enters college the individual has become aware of the forces swirling around him, the maelstrom of life in which he is caught. Through perspective he tries to give life meaning, and the only way he can affirm his view is through purposeful commitment. For as one wit translated the Greek inscription chiseled over the library entrance of a Midwest college, "Pep without purpose is piffle." Therefore, commit yourself to something; whether it be an activity, a sport, or an organization, and follow it with dedication, duty, and decision. This need not be on an Olympic scale; there are numerous opportunities close to home: the Tucker Foundation, the Glee Club, the gymnastics team, intramurals—any calling is great if greatly pursued.

Unless knowledge is tempered by a sense of perspective and a feeling of commitment, it can become dry, and if pursued long enough alone, suffocating. That is why it is these three facts together which are the key to a first-rate education and the catalyst for fulfillment in the years to follow. I hope you find it so.

It is a special privilege to introduce the next speaker. I take great personal pleasure in welcoming into the Dartmouth family the distinguished President Emeritus of Wellesley College, Vice President Ruth Adams.

Remarks by Vice President Adams

On this platform at a most impressive ceremonial occasion presided over by a most distinguished 20th century mathematician and philosopher, I sought to give myself reassurance by turning to the works of a 19th Century mathematician and logician to reinforce the remarks I wanted to make this evening. I turned to the work of Lewis Carroll—Alice in Wonderland.

Some of you will remember—indeed all of you should know—that the protagonist of that volume and its sequel is Alice, "a reasonable young lady." And in her adventures she encounters a number of fabulous beasts. I belabor my point if I say that for myself and the others of my sex there is a kind of wonderland quality in coming to Dartmouth.

At one point in her excursions Alice encounters the Griffon—a creature of no sentiment whatsoever—and the Mock Turtle—all sentiment—two fabulous beasts, and they turn to a discussion of Education, during which the Griffon rather sadly recounts the golden days of his educational career and tells what the curriculum was that he studied. It began, of course, with "reeling and writhing." It was followed by mathematics in its various subdivisions: "ambition, distraction, uglification, and derision." Another required course was "mystery" and then also the classics, which were, as you know, "laughing and grief." And I wish to point out, as Dean Brewster and Mr. Hauge have pointed out, that this is not a bad curriculum. We have each translated our remarks in a different way.

"Reeling and writhing" is elementary and immediate in a college career. You reel under the impact of printed forms to be filled out, you writhe under the constrictions of freshman seminars that are already filled by the time you register, and this whole pattern of twirling and wriggling is an idiom into which you move necessarily, automatically and inevitably. "Reeling and writhing" you have already begun to study.

In mathematics: "ambition." Ambition, insofar as it is close to aspiration, is healthy and good. I commend to you decent human ambition. It should be for a cause rather than for one's self, because if ambition is selfish, it negates its potential value.

"Ambition, distraction." Distraction is something one should provide for one's self. It is at times absolutely essential that one be distracted, that one relax, that one have fun. But it should be for fun's sake and not as an escape from responsibility. And distraction should be self-generated and self-directed, not directed towards others. You should not impose your distractions on other people who wish to concentrate, who wish to work.

"Ambition, distraction, uglification." Uglification is always bad and therefore we should know about it. Uglification, if it is personal uglification from neglect or hostility, should be seriously considered and rejected as irrelevant. When neglect or thoughtlessness uglify our landscape and our environment, we must know the sources of uglification and combat them. This should go as precisely to details as to resent the uglification of our buildings and our man-made domestic environment as a consequence of bad taste or shoddy production. We should resent the uglification of the mind that results from a narrow frame of reference, a kind of aridity which is beyond cultivation in every sense of the word, that results from an inability indeed a poverty—that makes comparison and judgment abortive. And we should combat the uglification of the spirit, which for me lies in a refusal to pay tribute to the goodness and strength of all mankind.

"Derision," our final branch of mathematics, is all right, I suppose, when it is a contempt for the bad. I find it, however, a bad technique in any situation and if it is directed towards people it is unforgivable.

"Reeling, writhing; ambition, distraction, uglification, derision; mystery." Mystery, ancient and modern. One should be required to cultivate a sense of what is unknowable, a sense of mystery from which there springs our capacity for wonder and awe. And it is right that at all times we should experience what it is to stand in wonder, to stand in awe.

Finally, the classics, "laughing and grief." Laughing is classic; grief is classic. They are and have been and will be required. We must be able to do both. We must be able to grieve. We must be able to laugh.

These are the curricula of the "fabulous beasts and the reasonable woman." Aspiring to the latter, I am glad to have joined the fabulous beasts.

Address by President Kemeny

Entering classes traditionally go to great trouble to establish the fact that there is something very special about them. You, the members of the Class of 1976, do not have this difficulty because you are indeed a very special class. You are the first coeducational class ever admitted to Dartmouth and the first class admitted under the Dartmouth Plan. The success of these two major innovations is going to depend on all of us, but particularly on you the members of the entering class. Since you were not here when we had our great discussion and debate over the past three years, perhaps it would be appropriate to review briefly why these decisions were made.

First of all, they were made because the faculty and the student body of Dartmouth College overwhelmingly supported coeducation. It was the consensus of both groups that Dartmouth would be a better place if both men and women were here side by side. This led to the memorable meeting of the Board of Trustees in November 1971 to consider the fundamental mission of the College which has traditionally been the training of leaders. The Board reached the judgment that in an age when it is clear that women will increasingly play roles of leadership in our society, it is important for Dartmouth to train both men and women for leadership roles. It was on that basis that the Trustees approved coeducation.

To turn to the second major decision—the Dartmouth Plan—I am quite sure that in the minds of many who approved it the crucial consideration was its linkage to coeducation. How could one add a significant number of students without spending many, many millions for new buildings—millions which incidentally, we do not have. And, clearly, the fact that the Dartmouth Plan would accomplish this was one major reason for its adoption, but it was by no means the only one. I shall say more about this later.

Many urged us not to try two major experiments at the same time. But we saw no way of trying one without the other. The more successful we are in implementing the Dartmouth Plan in the next few years, the larger the number of women students who will be admitted to Dartmouth College. We hope that in the next four or five years, by the time the Plan is in full operation, we will have achieved at least a 3-to-1 ratio of men to women in the undergraduate body. It is important to tell you, the entering class, that the Trustees did not vote either a quota or a desirable goal—we simply calculated how much one can achieve in a few years with limited resources. The Trustees have no preconceived ideas that that ratio is desirable or should be with us for a long time. Rather, they took this as the first practical measure, and when we complete phase one, I am sure that the Trustees will reassess the plan and start planning for phase two.

So much for the background of the decision-making. Today, as we celebrate the beginning of a very exciting new year, I would like to raise a few problems that I think may confront us in the year to come.

For more than 200 years in the undergraduate body Dartmouth has had an all-male (or nearly all-male) experience. Our brother institutions that went coeducational faced a number of problems in the initial year. It is my hope that we may be able to avoid many, if not all, of the mistakes they may have made, and this is one of many reasons why I am happy to have Ruth Adams with us: to try to warn us ahead of time before we make the same mistakes everybody else has made.

I have been told that some of our brother institutions had a tendency to pre-judge what it was that women wanted even before the women arrived on the scene. One of my favorite stories concerns an institution in which a group of all-male administrators decided what kind of feminine furniture would be appropriate for women students when they arrived on campus. A dormitory was furnished entirely with this beautiful "feminine" furniture and the administration was quite shocked when shortly after the women arrived all of that furniture was found on the lawn outside the dormitory. The women insisted on having furniture exactly like that of the male students. I don't know why—I don't think the furniture of the male students was that attractive—but we have tried very hard not to make the same presuppositions at Dartmouth.

There have also been a number of assumptions that women will automatically express different preferences in their academic choices. I am sure that there is some truth in this, but I suspect that it is exaggerated. I suspect that the differences among institutions may be greater than the differences among students of opposite sex on the same campus. We all know that Dartmouth men have interests quite different from those of Harvard men. It remains to be seen whether the academic interests of Dartmouth women might not be closer to those of Dartmouth men than, let's say, those of Harvard men. I am convinced that the factors that have played such a major role in attracting male students here for over two centuries will be the very same factors that will attract women students here. And therefore I am quite sure that just as it is often said that Dartmouth men are different, in the future it will also be said that Dartmouth women are different.

A great deal is on my mind as to what needs to be done to make this year successful. I know that there has been very strong endorsement of coeducation on campus and this is a major asset in facing our problems. But words alone are not enough. I suspect that there may have been quite a few who voted for coeducation simply on the grounds that they felt it would be nice to have girls around. And I must confess that it is nice to have girls around. But now we must make sure that these same girls become fully equal members of the Dartmouth community, and that will take a little bit of work.

Let me turn first to the faculty and those others who serve as advisers to women students. I would like to ask you in the strongest possible terms not to advise women students, for example, to enter the "feminine professions." I happen to be very sensitive on this topic because I know a young lady at another institution who would like to become a scientist. And throughout her first year several well-intentioned and kind gentlemen told her that a woman has no place in science. And she is getting very tired of hearing that. I personally feel that to say that science, for example, is an exclusively male profession is as ridiculous as saying that only women should enter the humanities.

The faculty was the single group that was most overwhelmingly in favor of coeducation during the planning period, and therefore the faculty now bears a special responsibility to assure educational equality to women. I hope very much that this will not be spoiled by preconceived notions that may belong to another age.

Let me next turn to male students on campus. I have heard many of you complain for years that the relationship in which you see women only as dates, most often during hectic weekends, is an unnatural relationship between men and women in this day and age. You argued this point eloquently and convincingly and you won your argument. Now you have to prove that you meant it. If you treat Dartmouth women as curiosities, or simply as more easily available dates, you will make a mockery of that which has been said over the past three years. I am glad that during these three years we had a very successful experience with the excellent exchange program, which is being continued. I think this has paved the road to successful coeducation at Dartmouth.

But I am particularly counting on the men and women of the Class of 1976 who have entered together and have not been preconditioned, and who hopefully will find the relationship we are all looking for: the natural way of men and women working side by side and treating each other as equals. Because in the last analysis the question of whether the women of Dartmouth will feel fully members of the Dartmouth community will depend on the attitude of the student body.

Let me turn briefly to the Dartmouth Plan. I said that it was necessary for coeducation, but I believe it is a plan with considerable educational merit. It will bring new freedom of choice to students, to the faculty, and even to the President of the College. For the first time the President will be able to choose when he takes his vacation, and I assure you that it will not be in the summer. I don't know why people have to be compelled to come in the summer—I think you should pay extra for the privilege of being in Hanover in that season. But, more seriously, the option available under the Dartmouth Plan of taking off six months at a time, even twice during your undergraduate career without delaying graduation, opens up new opportunities, some of which we have thought of and many of which I hope you will think up. The possibility of a better and more meaningful job is one important opportunity. The possibility of going off on a Tucker Foundation project and staying in the ghetto for an extra period just because you feel that you should do it is another very important opportunity. The possibility of going overseas and staying longer than one term is a third important possibility. And above all, I hope that these periodic significant interruptions will give you time to sit down and think about where you are going so that you do not face us on graduation day and say, "I have just never had time to think and therefore I have no idea what I have been doing at Dartmouth."

The question is: how will you-particularly you members of the Class of 1976—use this new freedom. I hope that you will not fall into the educational rut of required calendars but will take a fresh look and use your imagination to think up options we haven't even dreamed of. In that way you may set the pattern for a generation of Dartmouth students.

This is a special year. You can almost feel it in the air. Frankly I would not miss this year for anything. I know that we will make mistakes and I hope that we will learn from them. Probably we will have a bit of chaos during the year—we have already had some. But I must confess that I would rather be connected with an institution that is moving forward where there is excitement, where there are new ideas, and where there is chaos, than to be connected with an institution that is stagnating.

The feeling that in this particular year all of us are making an impact on the destiny of a great institution is an intoxicating sensation. And above all, you the men and women of the Class of 1976 have a special opportunity and therefore a special obligation. We will be watching your progress with great interest and I hope that some day, when we look back at this crucial turning point in the history of the College, we may speak with pride of the spirit of '76.

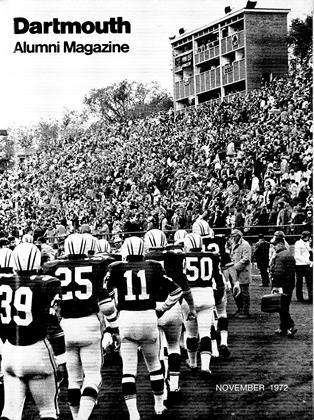

Dartmouth's first coed student body at Convocation

Dean Brewster addressing faculty and students.

Two pairs of twins are in the Class of '76: (left) Kipp and Kirk Barker of Garden Grove Calif being matriculated byDean Brewster; Debbie and Donna Humphrey of New York City with Dean of Freshmen Ralph Manual '58 at registration.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

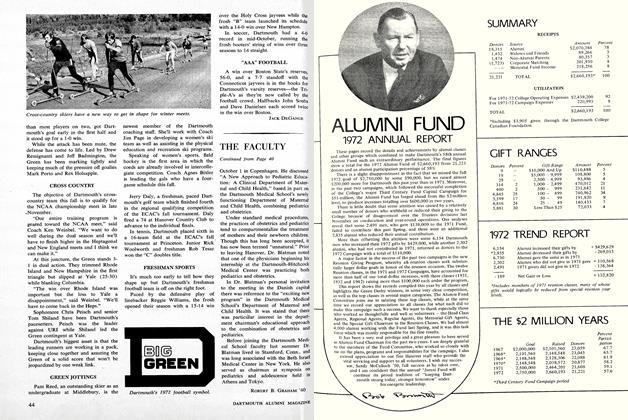

Feature1972 ANNUAL REPORT

November 1972 -

Feature

FeatureElection '72: A Historian's View

November 1972 By JAMES E. WRIGHT -

Feature

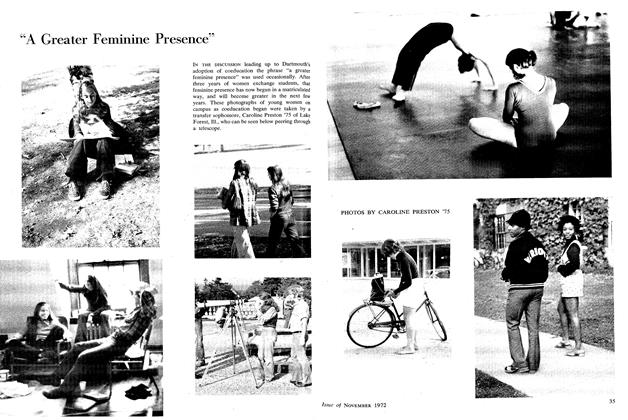

Feature"A Greater Feminine Presence"

November 1972 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1972 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

November 1972 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1972 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureToro's President

DECEMBER 1966 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJust a suggestion, Mr. President: an agenda for the eighties

OCTOBER 1981 -

Feature

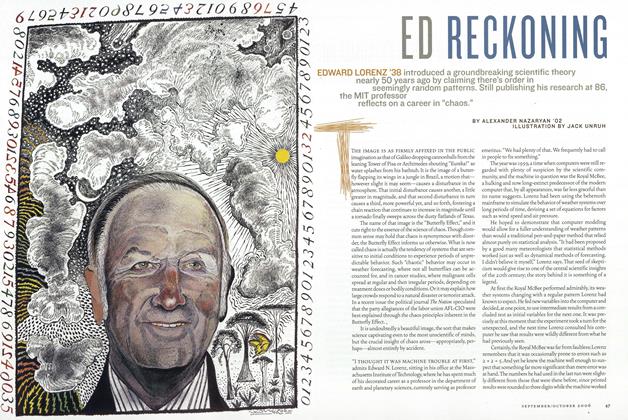

FeatureEd Reckoning

Sept/Oct 2006 By ALEXANDER NAZARYAN ’02 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Star from the East Named Dimitroff

MARCH 1995 By Bill Hartley '58 -

Cover Story

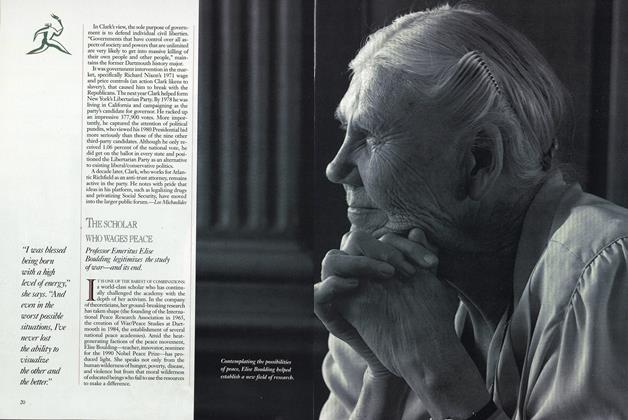

Cover StoryTHE SCHOLAR WHO WAGES PEACE

JUNE 1990 By Jim Collins ’84 -

Feature

FeatureGames Changers

Jan/Feb 2010 By LISA FURLONG