Address by President Kemenygiven May 4 as part of anall-day symposium oneducation at the College

I should like to begin by expressing my appreciation to the Committee on Educational Planning and to the Student Forum for arranging this occasion and inviting me to speak to you. It is very easy to get bogged down in the everyday routine and demands of one's office and I believe that every college president should be forced from time to time to consider the fundamental mission of the institution. It is equally important for the community as a whole to engage periodically in soulsearching and therefore I am happy that we are taking a day off from a very full and busy year to consider why we are here and what we are doing.

It is particularly appropriate that we pause to take stock at this time as Dartmouth College faces some very major changes. I have found it instructive to attend meetings of the 25th reunion classes. They are perhaps the most interesting reunions in which I have taken part, because our graduates 25 years out of college are usually at the height of their careers; they are far enough from their student days to have sufficient perspective to evaluate their education and to make a judgment as to whether that education had a lasting value. I am struck by the fact that this year's freshman class will be celebrating its 25th reunion in the year 2000. And that means that we have to consider what we should be doing today that will be meaningful to graduates of the College in the year 2000.

I have heard a number of discussions of the nature of liberal arts education and I must confess that I found them less than satisfactory. Typically they begin with some of the symptoms of discontent and very soon the discussion degenerates into a series of pet complaints and the elaboration of pet theories. Rarely do the discussions get down to the basic question of what the purpose of liberal arts education is. I am going to attempt to face exactly that question today. During the past few days I have been developing a set of basic premises that would define for me a liberal arts education, and in terms of which I believe such an education should be fashioned.

Altogether, I have identified eight such premises, five positive and three negative. They are:

(1) The college years are the best time to choose goals for one's life.

(2) Preparation for leisure time is as important as preparation for a job.

(3) It is important to acquire an overview of the breadth of human knowledge and activity.

(4) It is important for the development of the human mind to acquire mastery of one area of knowledge.

(5) It is important to understand tks problems threatening our civilisation.

And the three negatively stated premises are:

(6) We cannot teach everything.

(7) We cannot teach everyone.

(8) We cannot teach a student all that he needs for the rest of his life.

Let me start with the negative premises.

We cannot teach everything. That is a simple statement of fact. But I should make the premise stronger because even if by some miracle we could teach everything, any one student could learn only a very small fraction of what we would be teaching. The ideal universal man belongs to the age of the Renaissance or the Enlightenment, or perhaps to the Jefferson era. I have a strong suspicion that Mr. Jefferson himself may have been the last person to achieve that distinction. Why therefore do we have a tremendous urge for completeness in departmental offerings? Why is it that no self-respecting history department would be without an expert on the history of Afghanistan? Why is it absolutely necessary to have an expert on every single musical instrument or an expert in every branch of mathematics that has ever been invented?

These pressures lead to a proliferation of courses and a fragmentation of the curriculum. As a result the catalog contains a tremendous number of specialized courses. This may possibly enhance the reputation of our departments but it is a major disservice to the student and, after all, it is the student that the curriculum is designed to serve.

But there is a second negative effect of the desire to have great completeness in curricular offerings, and this is the fact that given the size departments that Dartmouth College has, if you are going to have an expert in every major area you get to the point where members of a department cannot talk to each other about their interests. It is certainly a problem that they cannot pinch-hit for each other and cannot share courses. Eventually one reaches the regrettable situation in which individual courses are owned by individual faculty members.

I think one of the interesting challenges in designing a curriculum is the following: Can we as an institution decide on those areas we would like to single out for special strength at Dartmouth College? Can we build groups of faculty members who are strong in these areas? And then significantly reduce the number of courses but make them all of high quality and most of them of broad appeal?

My second negative premise is that we cannot teach everyone. It may sound like an elitist statement but it is not intended as anything of the sort. It is merely a statement of fact. The number of students taught at Dartmouth College is a very small fraction of the total student body of colleges and universities in the country. And even if you say that Dartmouth has a select group of students, hopefully of very high ability, we still teach only a very small fraction of the students of high ability in the country. We are often told that we must offer such-and-such a course because if we did not offer it we would lose good students. My response is that most good students go elsewhere. And that statement is true for every academic institution in the country. I simply do not panic if we lose a few good students because there is some single course missing in the curriculum or some one program we are not able to offer. As long as we can attract 1000 very good students each year who are of high potential and who represent great diversity, we are fulfilling the role of the institution.

I do want to emphasize the importance of diversity, however. A homogeneous liberal arts institution is a contradiction in terms because learning takes place not just within the classroom but also from the interaction of students and teachers through shared experiences and through discussions. Therefore, a highly diverse faculty and student body is crucial to the success of a liberal arts institution. But as I said, we must make choices and I'm quite convinced that if, let's say, we cut the number of courses in half, we would have no more difficulty attracting a thousand outstanding and highly diversified students than we do today.

That is the type of choice we made when the institution made a commitment to equal opportunity. While we as a nation owe a commitment to all minority groups—and one long overdue —any one institution, particularly one of our size, cannot play that role simultaneously for all minority groups. While Dartmouth would always admit any student who is well qualified, the question is what special programs and what special support can the institution provide? And, as you know, the decision was made to single out two minority groups for special programs and special support as our significant contribution to solving a national problem.

One of these is the group of Black students, since their problem is of such major national proportions that probably every institution in the country must participate in this. In addition, we have made a commitment to Native Americans because of the long, historic ties between Dartmouth College and Indian Americans. I am very happy to note that this year we see many of those verbal commitments being translated into meaningful action and I believe that by the end of this calendar year we may say that we are indeed meeting those commitments. I mentioned the importance of diversification of the student body, and certainly the admission of a significant number of minority students is one tremendously important factor in that diversification. I am convinced that the educational experience of every student is much better because of that diversity.

My third negative premise is that wecannot teach a student all that he needsfor the rest of his life. There is simply too much to learn. In addition, a student in college is too unsure of what he or she will need in later life, and change is too rapid to guess what these needs may be 25 years hence. This fact has two major implications. The first one is that it greatly increases the importance of continuing education. You may have heard me refer on previous occasions to the remark of Ernest Martin Hopkins, 11th President of Dartmouth, who called for a lifetime relationship between an institution and its alumni, one that would provide opportunity to replenish intellectual reserves periodically throughout the lifetime of the alumnus. (Incidentally, that remark is from his inaugural address in 1916.) As you know, President Dickey made an important beginning in the field of continuing education, establishing the Alumni College, alumni seminars, and the Dartmouth Horizons program. I hope to encourage a major expansion of these programs. I believe it is absolutely necessary for the survival of our civilization that we break out of the pattern whereby education stops dead at a certain point in life and then individuals are supposed to work for forty years or more without interruption and without an opportunity, in President Hopkins' words, "to replenish their intellectual reserves."

The second implication of the premise is that the contents of many courses may have to be changed. How would we redesign the curriculum if we knew for certain that students will continue their education beyond college and beyond graduate school? Of course this is a question that each discipline must answer for itself, but I would like to give some partial answers of my own. Because of my belief that continuing education will be the rule rather than the exception, I put very low priority on the teaching of facts. They are soon forgotten and are not likely to have long-range impact on the individual. I also put low priority on the teaching of perishable knowledge no matter how popular the particular topic may be at the moment. I do put high priority on understanding of fundamentals in any discipline. I put very high priority on developing the ability to reason, and I put highest priority on learning in college how to learn because life itself is a learning process.

I should now like to turn to my five positive premises. The first is that the college years are the best timeto choose goals for one's life. If that is true, and if that indeed should be first among our premises, then facilitating the choice of goals for life should be one of the fundamental purposes of the institution. The reason I believe that this is the right time to make choices is that high school is generally too early—the typical high school student has not acquired sufficient maturity and usually does not know enough about the options open for a career choice. On the other side of college, profession- al schools are usually too specialized and usually keep students so busy that there is no time to think. And if the choice is put off until after professional school, it is too late.

Within college it seems to me that the first two years, before a choice of a major is made, must be the crucial years. And yet as I look around here and elsewhere as to what help we provide the students in making a fundamental choice for life, I am not satisfied. It is typical for courses offered preceding the major to be designed primarily for students who are going to go on in that major and not designed to help acquaint a student with what that particular discipline can offer. Nor are they designed to help him decide whether he should or should not enter that particular discipline.

This puts an enormous burden on advising during the first two years. I believe that our very active freshman advisory system is better than at most institutions, and I also believe that it is not good enough. Perhaps our advising is best in the third and fourth years when departments advise majors, but by then they are advising students who have at least tentatively made a commitment to their goal in life. And for some reason or other, in the sophomore year, the year when the key decisions are often made, we seem to abandon our students completely. We do not seem to have any systematic method of counseling students on career choice. Even more basically, how do we help the students to decide how to make a career choice? Let me ask what can be done, for we are justly proud of the fact that at Dartmouth there is a close relationship between all faculty, including senior faculty, and all students, including freshmen, within the classroom. Having heard a number of stories of sister institutions, I think this is one area where we can with considerable truth claim that we are ahead of most institutions. But outside the classroom we cannot make the same claim. There we do not have enough opportunities for similar close contact between faculty and students.

I would also like to see the development of introductory courses for those students who would like to have an overview of a discipline rather than take the first step into entering the discipline. I would of course like to see a better advising system and one that takes care of an entering student for two years rather than one. I would like to see more contact between undergraduates and role models; that is, contact between undergraduates and graduates of the institution and others who have been highly successful in individual professions who might spend a few days or a week on campus to talk to students to give them a feeling about what it is like to work in that particular profession. I would like to see better living conditions because the role of peers in making career decisions is very important and the living conditions in dormitories and fraternities are not truly suitable for the kind of serious discussion that would facilitate this kind of decision.

I feel that our off-campus programs can play an important role. Participation, for example, as a Tucker intern has helped many students to decide what to do with their lives. And I hope that these opportunities will be vastly expanded under the Dartmouth Plan, with new job opportunities, the possibility of apprenticing for six months to try out a proposed profession and, above all, the time to reflect. One sin that we as institutions have committed is taking four years of a student's life, that are important for choosing goals, and then giving the student absolutely no time to reflect on how to make these decisions. I hope very much that under the Dartmouth Plan the periods off campus, particularly six-month periods, will be most helpful in correcting that shortcoming.

Premise number two was that preparation for leisure time is as important aspreparation for a job. Remember that we are talking about the year 2000 and I am fairly sure that by that time most individuals will spend a great deal more of their time in what we call leisure time than on the job. And yet though we spend an enormous amount of time and effort training people to do their job, we often give them little or no help in preparing them for their leisure hours. I believe that the well-educated person will need both a vocation and

one or more important avocations to have a meaningful life. For this both curricular and extracurricular activities are important. Literature and the arts are avocations that make life meaningful for many people. Some may find that a field like mathematics as a hobby may be something that makes life meaningful. Almost any academic area if pursued in sufficient depth may in later life become an important component. And so may extracurricular activities. One must not underestimate the importance of sports from this point of view, quite aside from anything sports may do to improve the health of individuals, the old Greek ideal. In addition to that, sports are a major means for the outlets of emotion and have played a very important part in the leisure time of many adults.

I know that there are human beings for whom a profession is totally fulfilling. But such human beings are rare. If we prepare our students only for their professions and do not prepare them for the rest of their lives, we will be failing as a liberal arts institution. In that connection I believe we have just taken a major step forward with the implementation of a plan for coeducation. If it is indeed one of the major purposes of the institution to prepare a student for the whole of life, then it is very important that in the future at Dartmouth men and women will study together, will work together and will learn to respect each other. This may be our single major step towards preparing our students for all of life.

The third premise, and the one that usually is most discussed, is the idea that it is important to acquire an overview of the breadth of human knowledge and activity. Strangely enough, so far as I know no one disagrees with this premise. And most people agree that the four years of college are the time to acquire this breadth of human knowledge. The only question is: how do you achieve it? It happens that I made a study of the socalled distributive requirements a few years ago and I would like to read you a passage from an essay I wrote at that time:

Let us begin by examining the plans at two typical liberal arts institutions, Cornover College and Western Waynsley.

Cornover College requires a two-year sequence in "All the Ideas of Man." The first year covers "The discovery of fire to the Copernican revolution," while the second year deals with "The circulation of the blood to nonrepresentational painting."

Although the course is geared to the nonexpert, high standards are maintained. Students work very hard in this course. One sophomore was in the infirmary for three days, and he missed the entire Renaissance. The only complaint about the course is that the grading depends somewhat on who reads the final examination. For example, to the question "What was Newton's greatest discovery?", Professor Jones expects the answer "The laws of motion," while Dr. Brown requires as an answer "The calculus."

Students come out of the course with a magnificent stock of cocktail party conversation pieces. They know some one fact about each of 100 famous men. They can speak an intelligent sentence about Athens, Roman Law, the Dark Ages, the Rise of Science, the Impressionists, and Relativity Theory. And a cocktail party rarely requires more than one sentence on any one subject.

Western Waynsley has a totally different approach to the problem of breadth in learning. No one course is required, but the student elects a number of basic introductory courses. For example, each student elects four science courses, from six departments, but no two from the same department. Thus the student may elect either invertebrate zoology or vertebrate zoology, but selecting both semesters constitutes specialization.

When one adds to these "distributive requirements" the requirements in English, in foreign languages, and prerequisites for a major, the student has filled his entire schedule for the first two years. Thus, except for his chosen major, the student is not allowed to progress beyond a course numbered 1 or 2 in any subject.

It is a very demanding task to design a suitable course, of one semester duration, which will give the nonexpert an over-all view of the field. And students are not always appreciative of these difficulties. For example, the two eligible psychology courses are nicknamed "Terminology 1 and 2." The very popular European history course is, referred to as "Blood and Gore." Equally well-known are "Hamlet for the Illiterate," "Experiments that Should have Worked," and "Star-Gazing 2."

In selecting a college, a student should pay careful attention as to where psychology is classified. At Cornover College it is a science, and therefore a favorite means of social scientists fulfilling the science requirement. However, at Western Waynsley it is a social science and therefore available to science students who need an A in a nonscience course.

Having talked to graduates of both these institutions, I have come to the conclusion that well-rounding should allow for more depth than at Waynsley, without the necessity of the universal knowledge course-sequence at Cornover.*

Of course our own distributive requirements are much better than at these two fictitious institutions. The most common criticism of our distributive requirement is that it cuts down on the number of electives available to a student, and that is the one criticism that I do not understand, since practically every course in the catalog counts somewhere towards the distributive requirement. If the student is not interested in taking any of the courses that fulfill the distributive requirement, what is he interested in taking? I am afraid that I have very little sympathy for a student who, let us say, cannot find four courses somewhere in the social science division that he would have wanted to elect as free electives.

But I do have two criticisms of our own distributive requirement. The first is that it is basically a smorgasbord approach. The student samples a little of this and a little of that, and one hopes that it all adds up to a great meal. My second criticism is that I absolutely don't understand why the distributive requirements are by divisions. The divisions of the faculty are a partitioning for administrative purposes and at least to my mind they do not in a natural way correspond to divisions of human knowledge. Perhaps it would make equally good sense to require each student to take four courses from the most senior members of the faculty, four courses from middle-age faculty members, and four courses from junior faculty members.

I do not have a magic plan and I strongly suspect that there is no foolproof plan for distributive requirements, but I do have a number of preferences. I would like to see course sequences for non-specialists in several major areas of human knowledge. And by an area I mean something bigger than a department and I mean something more meaningful and more homogeneous than a division. I see nothing magic in three. I don't know whether there should be seven, eight or nine major areas into which one partitions human knowledge. I would like to see all of the faculty within an area cooperate in the development of first-rate course sequences, specifically for the non-specialists, and I would like to see each student explore several such areas in some depth. Obviously no student could explore all of these areas and that does not trouble me a bit. I would much rather see a student take four courses within the arts, or four literature courses, or four courses in philosophy and religion, or four history courses, rather than take one course in each of these four areas.

Finally, I have often heard in discussions that there are some subjects that are somehow by their very nature "liberal arts" while others are not. This is an assertion that I categorically reject. I believe that a student who spends most of his four years concentrating on, say, Russian Literature is just as much of a specialist as a student who spends four years concentrating on Physics. Both students have failed to achieve the objectives of the liberal arts education.

I have to recognize that there is one major roadblock in the way of the development of good distributive requirements and keeping open a sufficient choice for the student body. And I want to identify as the villains of the piece our graduate and professional schools, for two different reasons. First of all, they are the ones who tend to put strong requirements of pre-professional training on students. Of course their response will be that if you look in their catalogs the requirements are absolutely minimal and should leave students open to do whatever they want. In practice, however, this is not what happens. In practice they drop a great many hints as to what courses they would really like to have students take, and particularly today when it is so difficult to get into a professional school, most students panic and take everything that could possibly help them be admitted.

Secondly, I feel that our graduate and professional schools have a bad effect on undergraduate education because they are the cause for students being so terribly grade-conscious. I have sometimes said to a student that getting a C— in a course is really not going to ruin the rest of his life. But the student often responds: "Yes, but it may keep me out of medical school and that will totally change the rest of my life," and I have not yet thought of a good answer to that particular complaint. Because of grade-consciousness students are often afraid to be adventuresome. They are reluctant to try out ideas in areas of knowledge that they might find very exciting because they are not sure they can get the "A" or "B" that will assure them of getting into graduate and professional schools.

Somehow I feel that the opposite is the essence of a liberal education. One of the nicest things that ever happened to me was a letter. I received from a Dartmouth undergraduate after I failed him in a mathematics course. It was a very lovely letter in which he said that unfortunately all through elementary school and high school he had acquired a tremendous mental block about mathematics and therefore he really didn't have a ghost of a chance of passing my course. (Incidentally, he said he hoped I would recognize it was his failure and not mine.) And then he went on to say that the course showed him, for the first time, why there were some people to whom mathematics was a very exciting discipline. And therefore he wanted to thank me for the experience. That a student can fail a course and yet say that it was an important part of his liberal education to me holds a key to what we should be doing rather than what the graduate schools force us to do. I feel very strongly that we must not allow Dartmouth to become a preparatory school for our graduate schools.

The next premise is that it isimportant for the development ofthe human mind to acquire a masteryof one area of knowledge. In other words, I believe in the requirement of a major. But I believe in it not because it is important for professional preparation, though it may be that, but primarily for other reasons. There are very few mathematics majors who go on to become mathematicians and there are very few history majors who go on to become historians. But I am quite convinced that these students become better human beings from the experience of having to concentrate on a field exciting to them and immerse themselves in this to considerable depth. It removes a- superficiality that is only too common in our civilization today. However, I do not feel that there is any preordained list of what majors should be. I do not believe they have to be limited to pre-packaged things that students shop around for, and therefore I very much welcome the coming of special majors in which the student can take an active role in helping design his area of concentration.

But as I hear criticisms even of this minimal major requirement, something troubles me deeply. Perhaps I can best express it by recalling something from Bertrand Russell. Russell once wrote that as a young man he was quite depressed and had suicidal tendencies and the only thing that kept him from committing suicide was a deep desire to learn more mathematics. (Incidentally, history records that he lived to be almost 100.) Now it is not the fact that it was mathematics that fascinated him that is important in that particular statement, but the fact that here was a man for whom a desire to learn some field meant enough to persuade him not to commit suicide. It is that burning desire to learn something that is missing in so many students, and I can only wish it were more universally present.

My final premise is that it isimportant to understand the problemsthreatening our civilization. But it is difficult to say what the university can do to achieve such understanding. Of course, we can tailor some of our courses towards this need—indeed, it is important that we do so—because dedication without knowledge most often leads to catastrophe. We can offer special programs so that our students can become personally involved and can learn of the problems from firsthand experience. We are deeply in the debt of our Tucker Foundation for leading the way in such special programs. We can sponsor a variety of extracurricular events—lectures, films, all kinds of discussions—that help in this area and we can talk to students about those problems that deeply concern us.

But I believe that there are some things that a college or university cannot do. It cannot allow the campus to become a political battleground. Nor can it allow dissent on any issue to be stifled. If universities do not guard the right for all opinions to be heard, no matter how unpopular at the moment, then they abandon their oldest and most important mission. I believe that today's student is dedicated but I believe it only if he is willing to pay a price for this dedication. The student who is willing to do good work only when someone gives him course credit or credit for a term paper, or when someone is willing to cancel classes so that he can go out and do something he believes worthwhile, shows no evidence that he really cares.

The true test of sincerity, I believe, will come under the Dartmouth Plan. I will" be very much interested to see, for example, just how many students will take the fall term off this year in order to work full time for the candidate of their choice. This is easy to do under the Dartmouth Plan. I will be very much interested to see how many students will go on a Tucker Foundation internship without course credit, or go for credit and stay an extra term not for credit but purely out of conviction. I will be interested to see how many will use their off-campus terms to work for a cause they truly believe in. If the majority of students elect to do one of these things, then we will indeed have proof of the strength of our students' beliefs. And if that should materialize, that may be the single most important contribution of the Dartmouth Plan.

I have not attempted to describe the ideal educational system because I don't believe there is such a thing. I believe in a variety of approaches for a variety of purposes and for different individuals. I do not believe in a magic cure for all ills. It is often argued, for example, that small sections are automatically superior to large ones, and indeed in a course where faculty and student should have close relations and exchange of ideas, a small section is far superior. In another type of course where the purpose is to convey a large body of knowledge and the students would like to profit from a lifetime of expertise by the faculty member, it may be that the large lecture section is not just more efficient, but a better way of organizing this course. And I know from personal experience that such a course can be truly inspiring.

Any plan that you may draw up today that will look ideal to you is sure to look far from ideal to many others. To me the trick is to provide enough diversity and choice that 4000 different students can all find what they are looking for at one single institution. I believe firmly that the liberal education offered at Dartmouth is one of the best in the country. But it is good precisely because it is in ferment, because it is continually being re-examined, and because it is continually changing. And therefore, I hope that out of your discussions during the rest of this day will come many ideas that will make a Dartmouth education even better and more meaningful to future generations.

President Kemeny speaking in Webster Hall, to open last month's symposium.

John G. Kemeny, Random Essays, 1964, Prentice-Hall, Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Men and the World: Three Views

June 1972 By ALBERT H. CANTRIL '62 I, THOMAS F. BOUDREAU '62 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureWhitman at Dartmouth—100 Years Ago

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE SAMPLER

June 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Myth of the Munich Analogy

June 1972 By STEPHEN C. THEOHARIS '71 -

Article

ArticleResearch at Dartmouth on Fly Control

June 1972 By JOHN K. SANSTEAD '72

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Hold Conference

November 1956 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHeather McCutchen '87

March 1993 -

Feature

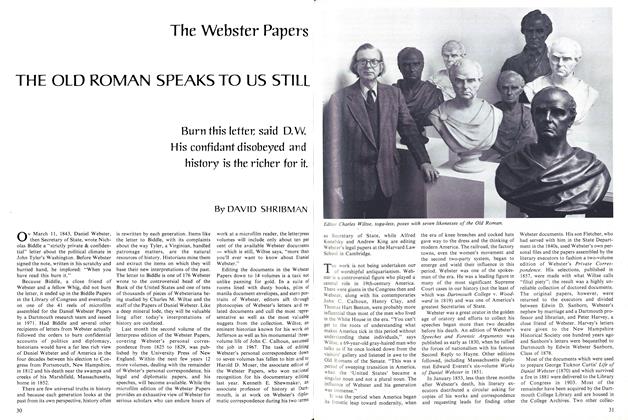

FeatureTHE OLD ROMAN SPEAKS TO US STILL

June 1976 By DAVID SHRIBMAN -

FEATURES

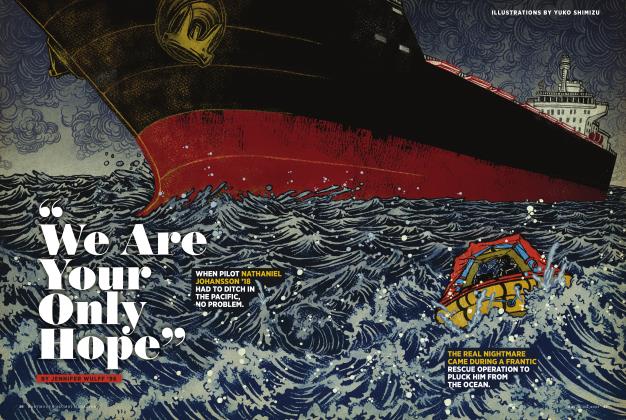

FEATURES“We Are Your Only Hope”

MAY | JUNE 2023 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureCOACHES

SEPTEMBER 1996 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK LIKE A PRO

Sept/Oct 2001 By NELSON ARMSTRONG '71