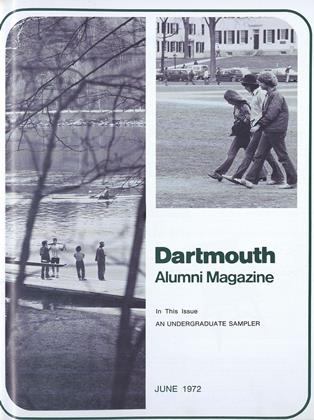

One hundred years ago, at Dartmouth's Commencement of June 1872, Walt Whitman came to Hanover as the invited guest of the senior class, and read his poem, "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free," written for the occasion. His audience little appreciated the literary event that should have been a cherished memory.

An excellent account of the visit, written by Prof. Harold W. Blodgett sixty years after the event, was printed in the February 1933 issue of the DartmouthAlumni Magazine. To mark what might be called "Dartmouth's Walt Whitman Centennial" we repeat it here:

A few weeks ago a Dartmouth undergraduate, much absorbed in James Truslow Adams' The Epic of America, noticed that the author had prefaced his book with certain swinging dithyrambs from Walt Whitman:

"Sail, sail thy best, ship of Democracy, Of value is thy freight, 'tis not the Present only The Past is also stored in thee ..."

And so on, for a page. Interested, he tried to find the source of the quotation. He inquired without success, and thumbed the "Leaves of Grass" in vain. No one knew. No one knew that these lines, and many others, were delivered by Walt Whitman himself over the unregardful heads of Dartmouth seniors at the June Commencement of 1872. "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free" he titled his poem, and at its finish a white-haired alumnus was heard to murmur: "Words, words; nothing but words!"

The ironies of literary fame are beautifully illustrated by this episode in Dartmouth's history. Whitman evidently accepted his invitation in the good faith that at length he had arrived, recognized and honored by the redoubtable guardian of literary reputation—retrenched academic opinion. To be sure, he lost this faith later. "College men as a rule would rather get along without me," he confessed in his old age. "They go so far, the best of them—then stop! Some of them don't go at all." But in 1872 he was feeling confident. He had been published in London, he had corresponded with Lord Tennyson, he had been hailed by Dowden in the Westminster Review, he had been translated in Germany and Scandinavia. So what more likely than his recognition by a conservative New England college? Elated, he wrote a long article about himself to be published immediately after his appearance at Hanover. "The late Dartmouth College utterance of the above-mentioned celebrity," he began, "is again arousing attention to his theory of the poet's art, and its exemplification in his writings."

Alas, the article never saw print, and furthermore Whitman never knew that his invitation came, at least in part, from the ardent desire of certain seniors to annoy the more conservative members of the faculty. Boston, New York, and Philadelphia were full of minor poets of unimpeachable character who would have been only too glad of a chance to read their innocuous lines to Dartmouth seniors. But Whitman in 1872 was a betenoir to many of his countrymen. James Harlan, Secretary of the Interior, had summarily dismissed him from the Department after a secret examination of the "Leaves" (filched, by the way, after office hours from Whitman's desk). Various reviewers had nearly exhausted their vocabulary of abuse over his book, and good people who did not know his incorruptible idealism, supposed him to be dangerous and unregenerate. And so the seniors had him up from Washington.

Unrest was in the air in the spring of 1872. As The Dartmouth remarked in its editorial column of the May issue: "These are indeed troublous times. The few who are so fortunate as to find on their return from the short recess that their connection with the College is not of a frail nature, have sufficient food for reflection in the warning fate of others, and the general instability of human affairs." Out of this unrest came the Whitman invitation. In explaining the matter to Bliss Perry, Whitman's biographer, Prof. Charles F. Richardson wrote: "In 1872 there was in the senior class a semijocose organization called 'Captain Cotton's Cadets'—not strictly a wild set, but not precisely the leaders of evangelical activities in the College. These 'Cadets' ran the senior elections of that year, and incidentally got Whitman to come."

On the other hand, the late Prof. E. J. Bartlett '72 did not recall, as he told the writer, that there is much in the notion that Walt was brought to Hanover to disturb the faculty. "Whitman was not sufficiently appreciated then," he said, "and we were all eager young fellows looking for something new." Among the restless of this class of 1872 was Charles (Chuck) Ransom Miller, late distinguished editor of the New York Times (so restless indeed that on Commencement Day Miller disappeared and was barely persuaded by his classmates to rush back to college in time to get into his regalia for the ceremonies). Miller, possessed of an alert and independent mind, was accustomed in his undergraduate days to read all the chief current periodicals in the reading room, founded four years before his coming to college.

"From these," writes his biographer, F. Fraser Bond, "he learned of a new voice in American letters—that of Walt Whitman. When the time came for the class of '72 to follow an annual custom and invite a distinguished poet to deliver an address and to read from his own works, Miller persuaded his fellows to ask the new poet." And so, partly from the motive of outraging the faculty, partly from a natural sympathy with iconoclasts, Walt Whitman was brought to Hanover and the following item appeared on the Commencement Week program:

"Wednesday, June 26th, three o'clock, P.M.: Anniversary of the United Literary Societies. Address by Rev. Edward E. Hale, D.D., of Boston, Mass. Poem by Walt Whitman, Esq., of Washington, D. C."

Whitman's sharing of honors with the venerable Unitarian clergyman was singularly appropriate, for Edward Everett Hale was among the first (in the NorthAmerican Review for January, 1856) to give Walt's poems a good hand.

If the Dartmouth seniors had expected Whitman to divert them with any astounding eccentricities (as Joaquin Miller frightened London dinner parties with his red shirt and bowie knife), they were disappointed. For Whitman was very demure, so demure that his poem was half inaudible. Those in the back of the church were in some doubt as to when he had finished, and those in front who managed to hear him were unimpressed. The house was polite and unenthusiastic. But the poet did not seem to mind. He liked his reception and in the evening he attended the Commencement Concert, applauding the singers by waving his arm and shouting "Bravo!"

But if Whitman's poem was uninflammatory, his appearance must have in some degree compensated the beholders. "He appeared on the platform," writes Miss Kate Sanborn, "wearing a flannel shirt, square-cut neck, disclosing a hirsute covering that would have done credit to a grizzly bear; the rest of his attire was all right." Elsewhere, Miss Sanborn commented: "Whitman was a great, breezy, florid-faced, out-of-doors genius, but we all wished he had been a little less au naturel." Prof. E. J. Bartlett remembers him "with a part of his brawny breast bare, and his long white gray hair and tawny beard set out by his Byronic collar made his head and face a study ..." Another witness was Francis E. Clark, who tells in his DartmouthDays how he saw Walt Whitman, clad in a blue flannel shirt open at the neck, shuffling down the main street of Hanover. "His voice was muffled and I could not hear his poem and probably could not have understood it if I had heard it, but I remember that as I passed him on the street, he gave me a gruff but hearty 'Good Morning.' "

While in Hanover Whitman was entertained at the historic home of Dr. S. P. Leeds, pastor of the College church. Here many notables had received hospitality—Emerson, Longfellow, and Holmes among others—and here Rufus Choate and Helen Olcutt had carried on their courtship. Dr. Leeds was absent in Europe when Whitman was entertained, and since he was a preacher of the old school who kept strictly within the articles of the church creed, it is to be presumed that he could have had little sympathy with Walt Whitman. Long afterwards Edward Leeds Gulick wrote, "I do remember Whitman's being at our house, and that Dr. Leeds was not altogether pleased at the fact." However, the pastor's wife, Julia Lockwood Leeds, graciously dispensed the traditional hospitality of their home, and she found the poet to be an ideal guest, considerate and not "troublesomely peculiar" in any way. At their parting Whitman presented her with an autographed copy of "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free."

It was from this house that Whitman wrote to his Washington friend, Peter Doyle: "I delivered my poem here before the College yesterday. All went off very well ... Pete, did my poem appear in the Washington papers—I suppose Thursday or Friday—Chronicle or Patriot? ... It is a curious scene here, as I write, a beautiful old New England village, 150 years old, large houses and gardens, great elms, plenty of hills—every thing comfortable, but very Yankee—not an African to be seen all day—not a grain of dust—not a car to be seen or heard—green grass everywhere—no smell of coal tar—As I write a party are playing base ball on a large green in front of the house—the weather suits me first rate—cloudy but no rain ..."

No, Whitman's poem did not appear in the Washington papers, nor did it arouse attention anywhere. The Daily SpringfieldRepublican, however, published the poem and announced succinctly: "Walt Whitman, being introduced, read his poem, 'As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free,' in which America's freedom and strength were set forth in the poet's own peculiar style, much to the disappointment of the expectant audience." But Whitman, as usual, did his own advertising. He wrote the long notice which never saw print, and he published the poem with several others in a little booklet, which he advertised as follows:

"The leading piece in this volume, and giving name to it, is the Annual Commencement Poem, delivered on invitation of the Public Literary Societies of Dartmouth College, N. H., June 26, 1872. It is an expression and celebration of the coming mentality and literature of the United States-not only the great scientists 'already visible,' but the great artists, poets, litterateurs, yet unknown. ..."

Regarded from the perspective of the times, the visit was not a success. TheDartmouth of the following year, June 1873, remarked caustically: "Walt Whitman delivered the annual poem at Dartmouth one year ago, and those who heard him on that occasion will appreciate the following from the DanburyNews." The scribe of the Danbury News had amused himself by quoting one of the more fragmentary of Walt's poems with the observation: "And here he stops. Not a word of how the battle resulted, but just drops down and leaves the reader to imagine the result. This is the secret of his success. His stops make him popular. The more he stops the more popular he becomes. If he should stop altogether the public would give him a monument."

But Whitman did not stop, and the irony of the situation turns upon itself, full-circle. For the unappreciated poem which Whitman read in innocent pride and unaware of the full reasons for his having been so signally honored, this half-unheard poem which he himself advertised and press-agented, turns out to be a genuine poem, quoted in a recent distinguished book and destined to be quoted again. The fame and influence of Walt Whitman is increasing year by year and Dartmouth may well be interested in his literary history.

Walt Whitman

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Future of Liberal Arts Education at Dartmouth

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Men and the World: Three Views

June 1972 By ALBERT H. CANTRIL '62 I, THOMAS F. BOUDREAU '62 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE SAMPLER

June 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Myth of the Munich Analogy

June 1972 By STEPHEN C. THEOHARIS '71 -

Article

ArticleResearch at Dartmouth on Fly Control

June 1972 By JOHN K. SANSTEAD '72

Features

-

Feature

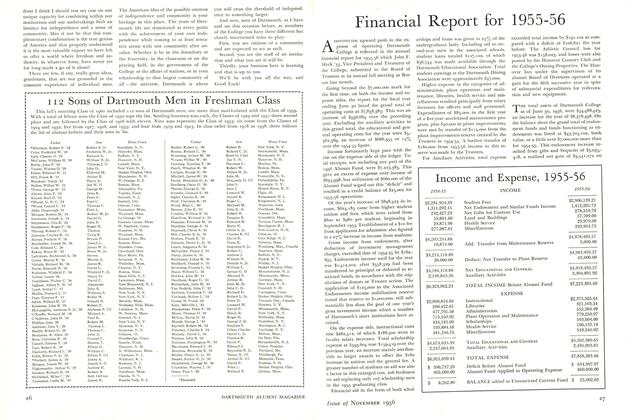

FeatureFinancial Report for 1955-56

November 1956 -

Feature

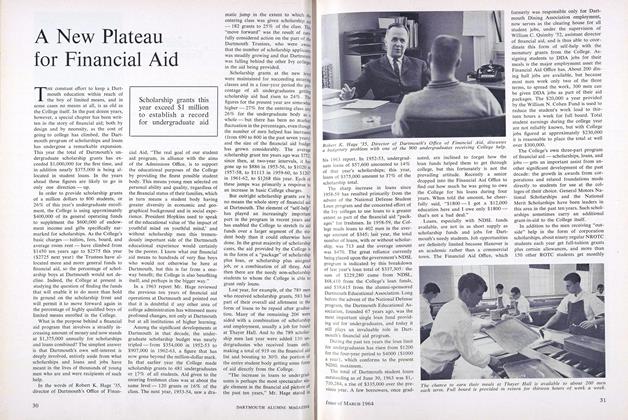

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

MARCH 1964 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 200TH COMMENCEMENT

JULY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureSports for the Multitude

JUNE 1964 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1963

JULY 1963 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureOliver Wendell Holmes Slept – and Taught – Here

May 1956 By ROBERT S. BLUM '55