The following article is an outgrowth of Steve Theoharis'Senior Honors Thesis at Dartmouth College. The thesis wonthe Jones Prize in 1971 as the best written essay by aDartmouth senior on a subject dealing with Americanhistory. The essay and thesis were written under mydirection.The article reflects the quality of the Honors Thesis, andit deals with a timely subject that is of considerableimportance to the past and future of American society.

—KENNETH E. SHEWMAKER Assistant Professor of History

Throughout the Cold War, there have been various factors influencing the formulation of American foreign policy. One of the most important and basic of these has been the lesson of Munich. The Czechoslovakian crisis of April through September 1938 and its settlement at Munich have taught succeeding generations a supposedly valuable lesson: appeasement of an aggressor will only encourage further aggression and, conversely, firmness will discourage further aggression. Time and time again, situations faced by the United States are declared to be analogous to that crisis faced by Great Britain and France. In this way, the "Munich Analogy" has had a pervasive influence on American foreign policy.

What happened at Munich must first be summarized. The primary actors in the crisis were Great Britain, France, Russia, Czechoslovakia, and Germany. At the heart of the dispute was the treatment of the German minority in Czechoslovakia. The crisis began in earnest on April 24, 1938 when Konrad Henlein, head of the German militant faction in the Sudetenland and acting under the orders of Adolph Hitler, made the Karlsbad demands. These were extreme and unacceptable to the Czechs. Hitler had ordered him to make his demands so extreme that the crisis would not be averted by negotiations. Hitler wanted to use the plight of the German minority in the Sudetenland to destroy Czechoslovakia, which posed a threat to his plans of domination. After the May crisis, during which the Czechs mobilized in response to reported German troop movements, the French and British, frightened by the prospect of war, took the initiative. They promoted negotiations between the Czechs and Sudetens, sponsored a mediator and applied pressure for concessions by the Czechs. When the situation worsened during early September, Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister of Great Britain, decided to take a more direct course. He met with Hitler at Berchtesgaden on September 15 and at Godesburg on September 22-23. At Godesburg, Hitler vehemently denounced an earlier agreement made at Berchtesgaden and demanded an immediate military takeover of the Sudetenland. At this point, Chamberlain broke off talks. On September 29, after a lastminute appeal for a conference was successful, Chamberlain, Hitler, Edouard Daladier, the French Prime Minister, and Benito Mussolini, the Italian Prime Minister, signed the Munich agreement. It called for the cession of the Sudetenland to Germany. There is no doubt that Great Britain and France pursued a policy of appeasement in dealing with Germany. Chamberlain believed he could appease Hitler and prevent World War II. He obviously failed when six months later Hitler took over the rest of Czechoslovakia and began to threaten Poland.

With this failure, many felt they had been taught a lesson. With the failure of appeasement, they assumed that an opposite course of action would have produced an opposite result. That is, they believed that firmness in dealing with Hitler would have discouraged any further aggression, thereby avoiding World War 11. Time and emotion have served to expand this specific lesson into a general law: a firm stand against an aggressor, avoiding all appeasement, will prevent further large-scale aggression. That is the primary lesson derived from the events of Munich. It is important to note that this lesson was not drawn from an actual experience but from speculation on an experience. A firm stand against Hitler was not even attempted in 1938. The unproven speculation that a firm stand would have stopped Hitler has been accepted as gospel truth by an entire generation, including those responsible for the formulation of American foreign policy.

The Munich analogy has played an influential role in American thinking. Munich, which has come to symbolize the entire experience the Western powers had with Fascism, became the basis of America's postwar foreign policy. The analogy is used by militant Zionist factions demanding increased U. S, aid to Israel. In the 1970 Congressional campaign, it was even used by President Nixon in connection with domestic affairs. Talking about the dissident elements in our society, Nixon observed:

A major reason why they (the dissenters) have gained such prominence in our national life, the major reason they dominate our television screens, the major reason they increasingly terrorize decent citizens can be summed up by a single word: appeasement. ... For too long, we have appeased aggression here at home—and as with all appeasement, the results have been more aggression, more violence.

The World War II generation became determined never to allow another Munich. It became conditioned to reject anything that appeared to be appeasement. During the Cold War, Americans began to see the possibilities of a Munich in every new crisis with the Communists, who came to play the role the Fascists had in the 1930's. The accusation of appeasement evoked the same intensity of emotion in the 1950's and 1960's that had been evoked in 1938. Since the leaders of the three postwar decades were all part of this generation, the events of Munich naturally affected American foreign policy.

For example, the Munich analogy was a prime factor in Truman's decision to go into Korea. The analogy has proved useful in another way; it allows a "hawk" to parade as a "dove." It allows a leader to justify a decision for war or intervention in the name of peace. The analogy holds one more attraction for political leaders. It gives their policies the same aura of moral righteousness that surrounded the Second World War. So it is these attractions plus the emotionality of the event that help to explain the influence of the lesson of Munich.

The overall impact of the Munich analogy can be separated into its effect on the leadership and on the citizenry of the United States. Unfortunately, there is little factual evidence documenting the analogy's impact on the people and much of what is discussed is conjecture. Therefore, the major thrust of this paper will deal with the analogy's effect on the leaders, since it is recorded in their speeches, memoirs, interviews, and books.

Before continuing, two things should be mentioned. Because the scope of this paper is limited, the term "leaders" will refer only to postwar Presidents and their major Secretaries of State. Secondly, it has been argued that the analogy has been used insincerely by political leaders, as a mere tool to sway public opinion. Until new sources appear, it is beyond my or any historian's ability to prove conclusively their sincerity or insincerity. Thus I shall take what they publicly said at face value. It is with this limitation in mind that I will discuss the influence of Munich.

The Truman administration was the first to show the effects of the lesson of Munich. The three major figures of that administration, Harry S. Truman, George C. Marshall and Dean Acheson, were all disciples of the lesson. Marshall, a man of great prestige, was highly respected by and listened to by Truman. He served as Secretary of State from January 1947 to January 1949, and as Secretary of Defense from September 1951 to January 1953. Like his generation, Marshall had been touched by the events of Munich. In a Memorial Day address in 1950 he stated, "There is nothing to be said in favor of war except that it is the lesser of two evils.'For it is better than appeasement of aggression because appeasement encourages the very aggression it seeks to prevent." Dean Acheson, Truman's Secretary of State during his second term, was a man sophisticated in foreign affairs yet he was not immune to Munich. In an address in 1951, Acheson asserted, "Aggression cannot be allowed to succeed; it cannot be appeased, regarded or ignored. To meet it squarely is the price of peace."

But it is with Truman that we come to the main propagator of the Munich analogy. Truman was relatively unskilled in the field of foreign affairs and needed all the help he could muster in dealing with the outside world. Being something of an amateur historian, the lesson of Munich must have proved irresistible to him. It provides the rationale for the Truman Doctrine and the policy of containment. The democracies of the 1930's failed to contain Fascism and the consequence was World War II. Therefore, containment of Communism will prevent World War III. Truman, speaking of his postwar policy, articulated the influence of Munich. "Our actions showed that we were for peace ... At the same time, we made it clear to all the world that we would not engage in appeasement. When the Soviet Union began its campaign of undermining and destroying other free nations, we did not sit idly by ... "

When he was confronted with an aggression in Korea that could have disastrous implications, Truman seized upon the analogy as a crutch to help him make the most momentous decision of his Presidency: In his memoirs, he recalls his thoughts after being notified of the invasion.

In my generation, this was not the first occasion when the strong had attacked the weak. I recalled some earlier instances: Manchuria, Ethiopia, Australia. I remembered how each time that the democracies failed to keep going ahead. Communism was acting in Korea just as Hitler, Mussolini, and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen and twenty years earlier.... If this was allowed to go unchallenged, it would mean a third world war, just as similar incidents had brought on the second world war.

In an address to the nation on Korea, Truman stated, "But we will not engage in appeasement. The world learned from Munich that security cannot be bought by appease- ment." Obviously, the Munich analogy had played a vital role in the ultimate question of foreign affairs—whether or not to go to war.

With the coming of the Eisenhower administration in 1953, the Munich analogy enjoyed its zenith of influence. The two major architects of foreign policy, Dwight David Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles, his Secretary of State from 1953 until 1959, had both learned the lesson of Munich well. In a speech in 1959, Eisenhower observed, "The course of appeasement is not only dishonorable, it is the most dangerous one we could pursue. The world paid a large price for the lesson of Munich—but it learned it well." Dulles echoed these sentiments in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee: "Indeed, experience shows that those who try in that way (appeasement) to buy peace in fact only increase the ultimate danger of war."

Two major aspects of their policy, the domino theory and collective security, are both directly related to Munich. The domino theory is the lesson of Munich restated. The domino theory tells us if we allow a country to fall to Communism, others will follow in the inevitable chain reaction. The lesson tells us that if we allow an aggressor to take our first domino in an effort to appease him, it will only increase his desire for the rest of our dominoes. Collective security can also be explained in relation to Munich. Dulles' "pactomania," which led the United States into signing a myriad of treaties, comes directly from one of the lessons of Munich. Many contemporaries contended that Munich grew out of a failure to adhere to collective security, that is, the failure of Great Britain and France to live up to their commitment to Czechoslovakia. Therefore, in order to prevent another Munich and another world war, we had to create a system of collective security and honor our commitments. As Dulles explained it in 1956, "All of these arrangements, in their present form, are the product of a sense of danger born of the aggressive and violent foreign policies of power-hungry dictators—firstly Hitler and then the Soviet and Chinese Communist rulers."

Eisenhower and Dulles used the analogy liberally in making specific policy decisions. Referring to West Berlin in 1959, Eisenhower stated, "Let us remind ourselves again what we cannot do. We cannot try to purchase peace by forsaking two million people of West Berlin." Explaining American intervention in Lebanon in 1958, Eisenhower told the nation:

In the 1930's the members of the League of Nations became indifferent to direct and indirect aggression in Europe, Asia and Africa. The result was to strengthen and stimulate aggressive forces that made World War II inevitable.

The United States is determined that history shall pot now fee repeated. We are hopeful that the action which we are taking will both preserve the independence of Lebanon and check international violations which, if they succeeded, would endanger world peace.

Eisenhower used the analogy in 1954 to try to persuade the British to join us in backing the French in Indochina. He wrote to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, "We failed to halt Hirohito, Mussolini and Hitler by not acting in unity and in time. That marked the beginning of many years of stark tragedy and desperate peril. May it not be that our nations have learned something from that lesson." Ironically Churchill, the "hero" of Munich, rejected Eisenhower's assessment and request for collaboration.

But it was in the crisis in 1958 over Quemoy and Matsu, two small islands off the coast of China, that Eisenhower stretched the analogy to the depths of absurdity. In a televised address to the nation, he contended that the defense of these islands was necessary in order to prevent World War III. He first invoked the memory of Munich and World War II.

Do we not still remember that the name "Munich" symbolizes a vain hope of appeasing dictators? ... Now if the democracies had stood firm at the beginning, almost surely there would have been no world war.

He then placed the Chinese Communists in the role played by the Fascists.

Let us suppose the Chinese Communists conquer Quemoy. Would that be the end of the story? We know that it would not be the end of the story. History teaches that when powerful despots can gain something through aggression, they try, by the same methods, to gain more and more ...

He then directly applied the analogy to the Western Pacific.

... a Western Pacific "Munich" would not buy us peace or security. It would only encourage the aggressors. If history teaches anything, appeasement would make it more likely that we should have to fight a major war ...

He finally concluded, deciding on the course of action the United States should take, "There is not going to be any appeasement."

It is apparent that the events of Munich had a profound influence on the foreign policy of the Eisenhower administration. In their striving to avoid another Munich, Eisenhower and Dulles not only exhibited an intransigence born out of the fear of appeasement—which might help to explain the downgrading of the Soviets' "peace offensive" in the late fifties—but also showed a tendency to stake the prestige of the United States on relatively unimportant issues, such as Quemoy and Matsu.

With the coming of the Kennedy administration in 1961, the influence of the analogy plummeted. The analogy still exerted an influence, but John F. Kennedy had the mind of a first-class historian and understood the dangers of using historical analogies. He attacked Eisenhower for his liberal use of the Munich analogy: "... let us remember in the future that foreign policy is neither successfully made nor successfully carried out by mere pronouncements—and that the use of such terms as appeasement, Far Eastern Munich, and national unity does not in itself institute a policy." Dean Rusk was not quite as sophisticated, and used the analogy as early as 1950 in his position as Assistant Secretary for Far Eastern Affairs: "We shall not tread the dismal path to disaster marked out during the thirties by Manchuria, Ethiopia, the Rhineland, Poland and Pearl Harbor. Aggression must be stopped in Korea."

But Rusk remained in the background, as did the Munich analogy, with one large exception: The Cuban missile crisis. In an address to the nation, Kennedy attempted to bolster his firm stand by invoking the analogy:

The 1930's taught us a clear lesson: Aggressive conduct if allowed to grow unchecked and unchallenged, ultimately leads to war . . . Our unswerving objective, therefore, must be to prevent the use of these missiles ... and to secure their withdrawal or elimination from the Western Hemisphere.

In light of Kennedy's sophistication and his criticism of Eisenhower's previous use of the analogy, he merits severe criticism for his application of the analogy. Furthermore, it can be considered as evidence for those who maintain that the analogy's use by leaders has been far from sincere.

Kennedy was peculiarly equipped to deal with the events of Munich, since he had written a book in 1940 dealing with the foreign policy of England in the 1930's. Entitled WhyEngland Slept, it is a scholarly work as opposed to the majority of the books of the period, which were emotional and vitriolic. Kennedy did discover one lesson. He wrote, "We must always keep our armaments equal to our commitments. Munich should teach us that; we must realize that any bluff will be called."

With the death of Kennedy in 1963 and the coming of Lyndon Johnson, the level of sophistication in foreign affairs went down and the influence of Munich accordingly rose. Johnson, like Truman, was largely uninitiated in the complex world of international relations and needed the analogy. He believed he had learned a valuable lesson from Neville Chamberlain and was obsessed by a feeling that America must oppose all aggression. The depth of this belief is reflected in a May 1965 speech on Europe.

On November 11, 1938—the 20th anniversary of the armistice— Munich was just six weeks old, and war less than a year away ... And when new aggression threatened, Western leaders yielded, to find that weakness only increased the appetite of tyrants.

In all of this America shared; by failing to support the league and by standing apart from the troubles of Europe.

And war came. Again the lights went out.

When the dawn arrived, twenty years ago today, it was a gray dawn. Tens of millions were dead and nations were shattered. Almost before the ashes had cooled, the shadow of Soviet ambition fell across the face of Europe.

It was, perhaps, fortunate that the new danger came when past failure was fresh.

For, we learned from the folly of the past ... the Atlantic nations replaced appeasement with firmness. We made it clear, in Greece, in Turkey, and in Berlin, that we would not yield one inch of European soil to aggression. As a consequence, Europe is safer from attack and closer to enduring peace than at any time since V-E day.

While the analogy may have figured in other decisions, such as the intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1965, its most celebrated use was in the decision to commit combat troops in Vietnam. In a speech in 1965, Johnson explained his decision:

Three times in my lifetime, in two world wars and in Korea, Americans have gone to far lands to fight for freedom. We have learned at a terrible and brutal cost that retreat does not bring safety and weakness does not bring peace. It is this lesson that has brought us to Viet-Nam ...

Nor would surrender in Viet-Nam bring peace, because we learned from Hitler at Munich that success only feeds the appetite of aggression. The battle would be renewed in one country and then another country, bringing with it perhaps even larger and crueler conflict, as we have learned from the lesson of history.

Once again, Munich played a dominant role in an American decision for war.

With the 1968 elections, we come to the Nixon administration. The major figure of that administration and the only one that needs to be considered is Richard Milhous Nixon. Nixon not only lived through Munich; he was tutored in it for eight years under Eisenhower. He learned the lesson well. In Six Crises he wrote, "Our failure to meet a Communist probe in Asia or Africa or Latin America only increases the probability that we will be forced to meet such a problem in Europe." In 1964, he called proposals to negotiate with the Viet Cong "surrender on the installment plan." In a speech in 1966, he discussed Vietnam,

What are our goals in Vietnam? Let us be sure we know what our goals are not ... They are not bases ... our goal is to prevent the conquest of South Vietnam. We believe this is a war that had to be fought to prevent World War III ... (some) say we should make whatever concessions are necessary to end the war, pay whatever price is necessary to get out of it. Why must we reject this thinking? ... We have to reject it because peace at any price is always an installment payment on a bigger war in three, four, or five years ...

In the 1970 campaign Nixon avoided controversy and the analogy, though Spiro T. Agnew noted that Humphrey "begins to look a lot like Neville Chamberlain ... maybe that makes Mr. Nixon look more like Winston Churchill." It was not until the Cambodian invasion in the spring of 1970 that Nixon revived the Munich analogy. In a pre-dawn meeting with student protesters he invoked the analogy. Recalling the incident, Nixon told reporters,

I told them that I know it is awfully hard to keep this in perspective. I told them that in 1939 I thought Neville Chamberlain was the greatest man living and Winston Churchill was a madman. It was not until years later that I realized Neville Chamberlain was a good man but Winston Churchill was right.

In his press conference on June 1, 1971, President Nixon used the lesson of Munich to defend American involvement in Vietnam and his plan for ending the war.

To allow a takeover of South Vietnam by the Communist aggressors would not only result in the loss of freedom for 17 million people in South Vietnam, it would greatly increase the danger of that kind of aggression and also the danger of a larger war in the Pacific and in the world. ...

The influence of Munich can be criticized on a number of grounds. Perhaps the most basic way would be to examine the source of the analogy, Munich itself. There are three major arguments supporting the thesis that a firm stand would have stopped Hitler. The first would have us believe that Hitler was bluffing and would have backed down at a show of force. There is reason to question the interpretation that Hitler was bluffing. "On the contrary," concluded Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, First Secretary of the Berlin Embassy, "he was not only resolved on war but was actually looking forward to it." His plans for the invasion of Czechoslovakia, his actions at Godesburg, and his vehement speeches all indicate that he desired a military solution. In his reaction to the Munich Conference, we find further proof that he was not bluffing. Rather than being pleased that his "bluff" had not been called, he was angered by the results. As Allan Bullock writes,

Yet Hitler was more irritated than elated by his triumph ... After Munich, the view gained currency outside Germany that Hitler had been bluffing all the time ... This view is one of the assumptions which most strongly colour discussion of the Munich crisis even today. It does not, however, correspond with the impressions of those who saw Hitler at the time. ... By allowing himself to be persuaded into accepting a negotiated settlement, Hitler came to believe that he had been baulked of the triumph he had really wanted, the German armoured divisions storming across Bohemia ...

The second major argument states that there was a conspiracy among the German generals to arrest and overthrow Hitler when he gave the order to invade Czechoslovakia. Theories of conspiracy populate all periods of history. However, according to Keith Eubank, there is little contemporary evidence supporting this particular conspiracy. John Wheeler-Bennett, in his history of the German army, concludes that there is no evidence but the flimsiest assertion that the conspirators were sufficiently prepared or resolute enough to strike.

Finally we come to the argument that the combined forces of England, France, Russia, and Czechoslovakia could have defeated Hitler in 1938. Czechoslovakia, having to face the brunt of the German army and air force without any kind of substantial aid from her allies, could not have lasted more than a few weeks. As for Russia, there is a great deal of speculation as to whether she ever really intended to help the Czechs. Perhaps Russia intended to use the condition that France fight first and geographical factors to stay out of the conflict. The English ambassador to Russia, Anthony Verekim, the German ambassador Count von der Schulenburg, and American Soviet expert George Kennan all arrived at this conclusion. As for England and France, neither was ready for modern war. France was politically, morally and militarily weak. Politically, she was extremely unstable in this period, with four governments in ten months. Morally, there was corruption in the Chambes des Deputes, the Senate and the army. There was little enthusiasm for war. Militarily, her army was huge but with only two light armored divisions, and her air force was, in the words of Charles Lindbergh, "almost non-existent from the standpoint of a modern war." Furthermore, her strategy was hampered by the Maginot mentality, that is the waging of a defensive war behind the Maginot Line. The English were not in much better condition. The Navy was the only branch of the armed services prepared for war, yet the effectiveness of the navy was of questionable value in a localized land war in Central Europe. England's army was small and ill-equipped. Her air force consisted of 759 planes, most of which were outdated and slow compared with the modern German air force of 2800 planes. As the Chiefs of Staff said, "To take offensive against Germany now would be like a man attacking a tiger before he has loaded his gun." It is clear, from this brief survey, there is little evidence that the allies were in a position to win a localized war in 1938.

Hitler was not bluffing, would not have been overthrown or defeated in war in 1938. In other words, the lesson of Munich is invalid for Munich itself, which certainly raises grave doubts as to its validity for situations and crises faced by the United States in the past, present, and future.

Of course, the preceding argument is, like the so-called lesson of Munich, speculative. Like all historical speculation it is susceptible to criticism. ... An analogy is only as good as the number of identical factors in the two cases being compared. American statesmen have ignored this vitally important fact in applying the Munich analogy to a wide range of crises. Its misuse can be seen by examining one of its applications in depth.

The Munich analogy has been used to justify American involvement in Indochina. ... In a number of important respects, Munich and Vietnam differ strikingly. Consider the background of action, Munich took place in Europe, a highly developed continent of stable and well-established boundaries. Southeast Asia, underdeveloped with artificial boundaries, is in the chaotic throes of revolutionary ferment. Compare the major characters. England and France were weak in 1938; the United States has a powerful military machine. Hitler had his powerful Wermacht; Ho Chi Minh's ragged bands of Viet Cong or the North Vietnamese regulars hardly pose an equivalent threat. Czechoslovakia in 1938 was a strong, democratic state, a far cry from the corrupt and repressive South Vietnam of Diem, Ky or Thieu. Compare the two aggressive leaders. Hitler was a madman obsessed with plans of world domination, while Ho Chi Minh was primarily concerned with attaining independence from the Western powers. The question in 1938 was largely a political one; in the postwar era, the movements in Asia have been broadbased, involving massive social and economic as well as political factors. Aggression in the 1930's Was the crossing of borders. Is the artificial line set up by the West between North and South Vietnam a viable one when the country previously had been united for thousands of years? Is it really aggression for a North Vietnamese regular to cross into the South Vietnam he may originally have come from, when most Vietnamese see their country as one, when Marshall Ky is a North Vietnamese and Pham Van Dong, premier of North Vietnam, is really a South Vietnamese? As with its applications in Lebanon, Quemoy and Matsu, Korea, West Berlin, and Cuba, the events of Munich are substantially different from the event it is compared to and therefore useless as an analogy.

The use of the analogy can also be criticized on the grounds of the unfortunate tendencies it encourages. It encourages oversimplification.... To understand a complex issue like Vietnam in the simple terms of Munich is to prevent any real comprehension or rational discussion of it. The usE: of the analogy also encourages the avoidance of hard questions such as: Is Quemoy and Matsu or Lebanon or any country that is being considered really necessary for our national security? Is there a Communist plan for world domination? What are the moral and strategic implications of our involvement in Southeast Asia?

Finally, if the lesson of Munich is correct, why are we lighting in Vietnam? Postwar policy has for 25 years used the lesson, and yet there is still aggression. After Korea, the suppression of the Huk rebellion in the Philippines, the suppression of guerrillas in Malaya, and the sending of American troops to Southeast Asia—all evidence of a firm stand which should discourage Communist aggression—why did it persist in Vietnam? If our use of subversion and arms in Guatemala in 1954 shows that we would not countenance Communist aggression in Latin America, how did Castro win in 1959? If our harsh policy towards Communist Cuba, including an invasion and a blockade, show our firmness, then why the Dominican uprising of 1965? It is clear that the Munich analogy and its lesson are but abstractions in the minds of men, with no relevance to the real world. ...

Thus it is necessary for us immediately to reexamine not only the use of the Munich analogy but many of the assumptions and preconceptions, such as the policy of containment, which are indirect results of our acceptance of the experience of the democracies in the 1930's as a model for our actions in the postwar world. America's relationship with Russia and China is, because of military, social, technological and ideological factors, unique in history and, as such, deserving of unique methods and solutions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Future of Liberal Arts Education at Dartmouth

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Men and the World: Three Views

June 1972 By ALBERT H. CANTRIL '62 I, THOMAS F. BOUDREAU '62 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureWhitman at Dartmouth—100 Years Ago

June 1972 -

Feature

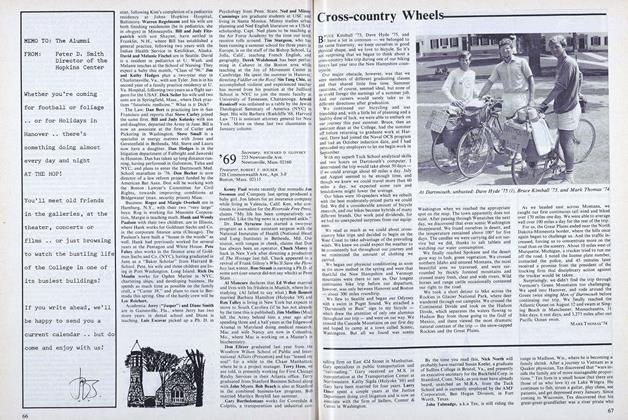

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE SAMPLER

June 1972 -

Article

ArticleResearch at Dartmouth on Fly Control

June 1972 By JOHN K. SANSTEAD '72