Though he has published almost 100 articles on birds and wildlife in professional ornithological journals, has achieved an international reputation for his behavioral studies of woodpeckers, and has been elected a Fellow of the American Ornithological Union, Lawrence Kilham M.D. denies being a professional. On the contrary, "Virology is my profession," he wrote upon retirement as professor of microbiology at the Medical School in 1975, "but I've always been leary of pouring one's whole life into one narrow speciality. ... I have been, for as long as I can remember, much interested in ornithology and natural history. I never wanted to spoil my interest in these subjects by being a professional. They go well with other things."

Never Enough of Nature demonstrates that Kilham is right in maintaining the distinction. He is genuinely an amateur - emphatically not in the sense of "sub-professional," but in the most nearly basic, etymological sense of that word: a devotee, a lover.

The general reader's interest in Kilham's book is less likely to be engaged by the literal, informational content than by the implied quality of the mind which conceived it. To be sure, the book informs; it is in effect the condensed record of a lifetime spent in observing living creatures. It is composed of excerpts from earlier wildlife articles rewritten for the layman plus selected entries from Kilham's field journals, the whole thematically arranged into 22 coherent chapters.

But it is more. For all his scientific knowledge and professional methodology, Kilham is no detached, impersonal observer. The book is clearly infused with the observer's love of what he is observing. Love and, in addition, wonder. Like Kazantzakis' character Zorba the Greek, whom he is fond of quoting, Kilham too "sees every day as if for the first time." Wonder, spontaneity, zest: they seem to follow naturally from Kilham's love and understanding of "nature at the center of things."

"Is not nature enough?" Kilham asks himself at one point in the book. "Yes and no," he answers. "Nature must include human nature." And so to the impulse from the vernal wood Kilham adds the knowledge which comes from books. Thoreau is of course de rigueur - and Kilham has read him thoroughly - but few ornithologists, I venture, have also read Euripides, William Blake, Browning, Sir Thomas Browne, and Wordsworth. Kilham has. Though marred by an occasional solecism that escaped editing, Kilham's writing reflects an intellect which has ranged as widely through the seminal literature of the Western humanistic tradition as through the specialized literature of ornithology.

Impelled no doubt by our legitimate concern for a ravaged environment, nature writing has become an "in" thing. A kind of debased neo-Wordsworthianism has become chic. And frankly, many of the overwrought (and usually over-priced) coffee-table nature books which pour from the presses nowadays seem pretentious: those too dramatic, contrasty color plates; those breathless purple-prose panegyrics to rainbows and sunsets; those anthropomorphic ooh's and ah's over this or that specimen of untamed fauna or uncultivated flora. From all of this Kilham's small, hand-illustrated, unprepossessing book comes as a relief. He is a trained observer knowledgeable enough to understand what he is seeing, tough-minded enough to know that nature is both murderer and mother, yet sensitive enough to retain his awe and love for the process.

NEVER ENOUGH OF NATUREBy Professor Lawrence KilhamDroll Yankees, 1977. 273 pp. $9.95

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureScions of Rhodes

January | February 1978 By Daniela Weiser-Varon -

Feature

FeatureOf Sun-Gazers and Seal-Hunters

January | February 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

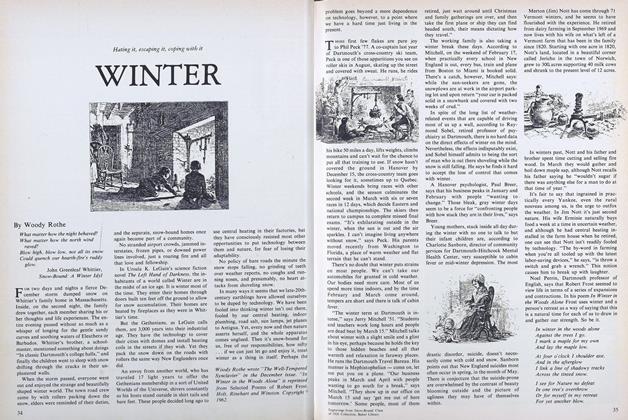

FeatureWINTER

January | February 1978 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

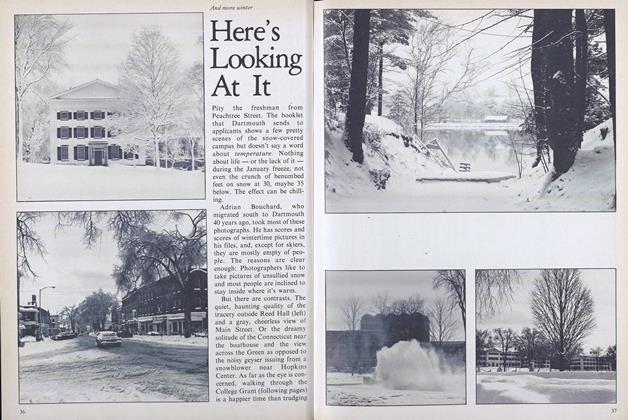

FeatureHere's Looking At It

January | February 1978 -

Article

ArticleGuardian of the Oasis

January | February 1978 By M.H. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

January | February 1978 By WALTER C. DODGE

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksAn Attendant Lord

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksSeeing Tilley Plain

OCT. 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksBound by Emotion

NOV. 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a realist among the Cassandras and one microcosmic answer to a macrocosmic question

NOV. 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

MARCH 1929 -

Books

BooksEVALUATION OF DEPOSITS DURING PROSPECTING AND EXPLORATORY WORK.

JUNE 1963 By ANDREW H. MCNAIR -

Books

BooksITALY ON FIFTY DOLLARS

By G. C. W -

Books

BooksTheir Message

May 1980 By Laurence L. Edwards -

Books

BooksAsking Deep Questions

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Richard Eberhart '26 -

Books

BooksAN OUTLINE OF SENECA CEREMONIES AT COLDSPRING LONGHOUSE

November 1936 By Robert McKennan '25