Symptomatic of a sea change in the climate of the times, Dartmouth Commencement 1972 was essentially a happy time for the 1000 degree recipients and their 5000 friends and family members who filled the lawn in front of Baker Library to participate in the academic pageantry on Sunday morning, June 11.

Perhaps because pressing contemporary issues had been faced Saturday in a series of seminars featuring several of the honorary degree recipients, old-fashioned nostalgia, sentimentality, and the measured march of familiar forms reigned at Commencement over the mood of cynicism, blazing idealism, righteous anger, and frustration that had marked graduation ceremonies in recent years.

In a sense, Commencement 1972 also marked the end of an era as Dartmouth graduated its last all-male senior class—6Bs members of the Class of 1972 and 74 men from earlier classes—amid a pervasive awareness of the advent of coeducation in September. (In the Class of 1973 will be 30 women seniors who were junior-year exchange students this past year, who were admitted as transfer students, and who will be graduated next June as Dartmouth's first female A.B. recipients.)

In his valedictory to the Senior Class, President Kemeny charged them, as both agents of change and as the last all-male class, with "a special responsibility to monitor Dartmouth's progress in coeducation as well as in its traditional concerns for making the College ever a better place while preserving that which historically had made Dartmouth a unique institution."

At the same time, he charged the graduates who witnessed—and participated in—the eventful years of protest and demonstration on campuses everywhere "never to lose your idealism and dedication." He praised the seniors for their world-wide concerns, yet reminded them that "some of the most urgent problems of the world are faced by neighbors in our own communities."

A similar theme of individual concern threaded through the message of class valedictorian Ross Kindermann of Fox Point, Wis., a math major and computing specialist. While praising his classmates for their "highmindedness and their opposition to war, hatred of sham and sympathy for the world's hungry," he urged them to put that idealism to what he called the "real test" by loving one's neighbor. "It's quite a simple matter for us to love a starving Latin American peasant," he said, "simply because we have never had to live with one. It is even easier for us to love several thousand starving Latin American peasants. (But) time and again, the noblest abstract principles retreat when confronted with the concrete situations which we are called upon to face in our everyday lives."

He took direct issue with last year's valedictorian whose eloquent plea for help in finding a purpose in life was suffused with a tone of despair. Rather, Kindermann warned that "self pity leads nowhere." (The texts of both valedictories appear in this issue.)

The impact of the individual in world affairs was also reflected in the six honorary degrees which President Kemeny awarded, in addition to the 759 baccalaureate and 240 advanced degrees. Those honored were Trustee Emeritus Dudley W. Orr '29, Doctor of Laws; Chinua Achebe, African novelist from Nigeria, Hannah Arendt, writer and teacher, and Walter Cronkite, CBS-TV news correspondent, all of whom received Doctorates of Letters; Arthur L. Mayer, motion picture executive and Dartmouth professor, Doctor of Humane Letters; and Dr. Merlin K. DuVal Jr. '44, Assistant Secretary for Health for HEW, Doctor of Science. Their citations appear on Pages 22 and 23.

In the context of approaching coeducation, President Kemeny took the occasion of the luncheon of the General Association of Alumni given by the Trustees in honor of the 50-year Class of 1922 to underscore that Dartmouth's unique capacity to invoke the love and loyalty of its alumni already has shown its constancy in an era of continuing and fundamental change.

As evidence he read a letter of thanks from a young woman who had just completed the academic year at Dartmouth as an exchange student and who was one of the 100 among the 150 women exchange students at Dartmouth this past year who had applied for admission to the senior class as transfers. She was not accepted, President Kemeny explained, not because she was not qualified but simply because of limits on the number of exchange students whom Dartmouth could accept as transfers from a single college.

Yet, President Kemeny said, she wrote to thank Dartmouth "for the most wonderful year I've ever had." She explained that she had been exposed to academic opportunities unavailable to her before, and, as importantly, "came to know what school spirit really is and came to love Dartmouth as much as any alumnus ever could as an institution that could do no wrong—except that wrong it did in not accepting me."

The same note stressing Dartmouth's core constancy in the face of change was sounded by John D. Dodd '22, retired vice president of the Bell Telephone Company of New York and a former Trustee, who gave the address for the 50-year Class, printed in this issue. Reviewing the almost incredible changes that have occurred in this country and the world in the half century since the graduation of the Class of 1922, last of the really small classes, Mr. Dodd stressed that its members had learned to live with change "as a way of life." He predicted that they would also adjust to and support the changes coming to Dartmouth in the forms of coeducation and the Dartmouth Plan for year-round operation.

"I believe you'll find the Class of 1922 working as hard for Dartmouth's future as it has in the past, to the end that Dartmouth may continue its pursuit of excellence in education as one of the nation's leading private institutions of higher learning."

Although the general mood was traditional, four innovations were introduced into the combined Commencement and Baccalaureate exercises.

There was no outside speaker for the first time since 1946 when that practice was reinstated in modern times with an address by Harold E. Stassen, former governor of Minnesota and presidential aspirant. The omission represented an effort to keep the total ceremony to a reasonable length and still retain the individual award of degrees. In place of an outside speaker at Commencement, four of the six honorary degree recipients participated Saturday in a series of seminars ranging from Mr. Achebe's analysis of African literature and Mr. Mayer's personal review of his life-long "love affair" with films, to a panel on "Truth in Government," featuring Professor Arendt and Mr. Orr, along with Government Professors Laurence Radway and Roger D. Masters and seniors Richard Zuckerman, former editor of The Dartmouth, and Bruce J. Shnider.

In another break with tradition, the Rt. Rev. Mnsgr. William E. Nolan, chaplain of Aquinas House, Catholic student center, gave the invocation at both Commencement and the Naval ROTC commissioning ceremony, while the Rev. Paul W. Rahmeier, chaplain of the College and acting dean of Tucker Foundation, gave the benediction. In the future, it is planned to invite clergy of the local churches serving Dartmouth students to participate in Commencement in this way on a rotating basis.

For the first time also, diplomas were handed out in reverse alphabetical order so that Joel H. Zylberberg of University Heights, Cleveland, who all his life has been bringing up the rear of most organized lines, received his degree first.

Meanwhile a 30-year formal relationship between Dartmouth College and the U.S. Navy came close to an end with the commissioning of 16 graduating seniors as Navy ensigns. Another ten cadets, who have completed their military science. program but must now finish their senior year studies at Dartmouth, remain to be commissioned in June 1973. But the commissioning this Commencement weekend brought to a close the formal academic program under a three-year phase-out of all ROTC programs recommended by the faculty the first week in May 1969 and approved by the Trustees.

The generally relaxed tone of the weekend was set at Class Day exercises on Friday in a traditional gathering at the Bema given over for the most part to humor and nostalgia, with two poignant exceptions.

They were the two senior class students who were black, who somberly and sadly reminded their classmates and their families that in June 1972 barriers of race and prejudice still cloud the future. Both men with outstanding college records, they are Jesse J. Spikes of McDonough, Ga., Dartmouth's sole Rhodes Scholar this year, and Stuart O. Simms of Baltimore, Md., co-captain of the 1971 co-championship Ivy League football team.

It was clear that, despite their successes, they could not entirely agree with C. William Pollack of Nacogdoches, Texas, starting quarterback on the 1971 football team, a Phi Beta Kappa scholar and class president, when, speaking as senior class marshal, he looked back and described Dartmouth as "the friendliest and happiest place I've been in all my life." Yet they, too, spoke in the end of challenge and hope, though they could not echo the humor of the other speakers.

At the graduate level, where, as in the past, several women received degrees along with the men, three husband-wife pairs were awarded advanced degrees together. Sidney W. Marshall '65, of Milwaukee, Wis., and his wife, Halina, a native of Warsaw, Poland, and a graduate of the University of Lublin, both received Ph.D.'s, he in engineering and she in psychology.

Among the Tuck School graduates, E. George Bellows '67, of Haworth, N.J., and his wife, the former Margaret Andrew of Columbus, O., became that school's first husband-wife team to earn an M.B.A., and they are now both starting jobs in Columbus, O. For the Bellows, there was the added distinction of having still another of that name getting the M.B.A. degree. The third member of the family was George's younger brother, Jeffrey C. Bellows. Watching them all were Mrs. Bellows' father, Dr. James M. Andrew '45, and her brother, Blair, who just completed his freshman year at Dartmouth.

Finally, a rare double—two master's degrees—were awarded to T.P.N. Sinha of New Delhi, India, who simultaneously received a master's degree in engineering from Thayer School and the M.B.A. from Tuck in what has to be an academic tour de force.

In that vein, the graduating seniors also distinguished themselves in academic honors. An even 150 men were elected to Phi Beta Kappa, having achieved a four-year grade average of 4.4 on a 5-point scale. Sixty-seven were graduated summa cum laude, 120 magna cum laude and 175 cum laude, while a whopping 58 per cent of the A.B. recipients earned distinction or higher in their majors, including 62 with highest distinction, 129 with high distinction and 250 with distinction. Quite an ending to a hectic four years, 1968-72.

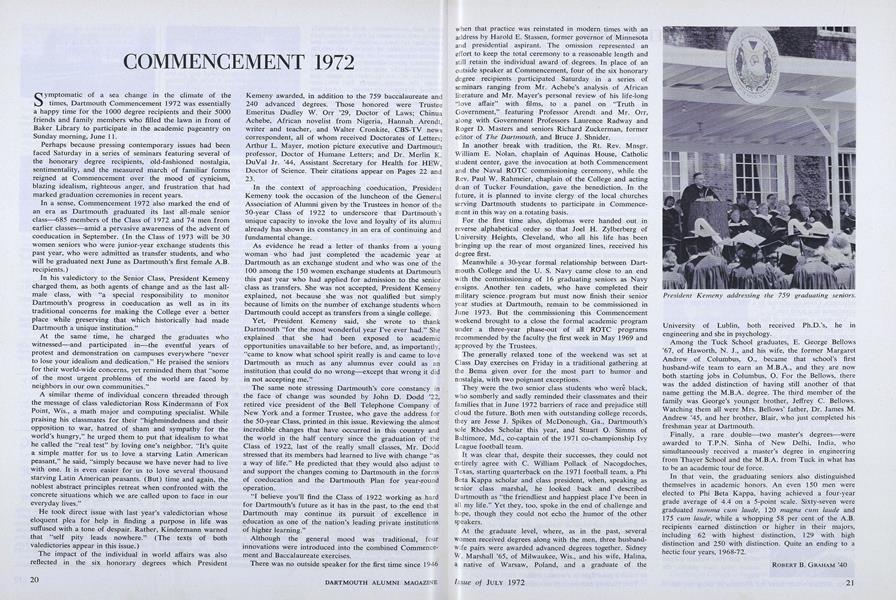

President Kemeny addressing the 759 graduating seniors.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

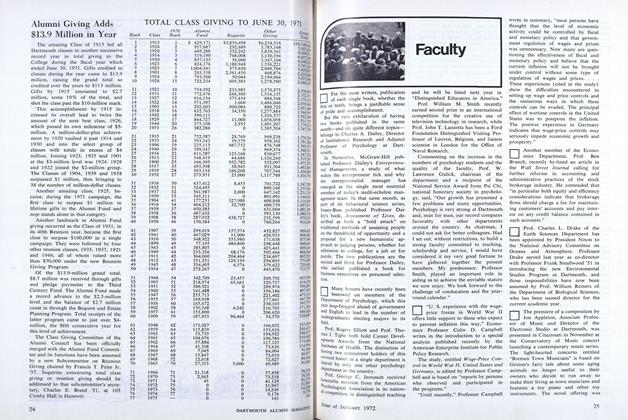

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

July 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

July 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSenior Valedictory

July 1972 By ROSS P. KINDERMANN '72

ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

-

Feature

FeatureNew Environmental Studies Program To Be Launched in the Fall

JUNE 1970 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

JANUARY 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

JUNE 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

OCTOBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

JANUARY 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

OCTOBER 1964 -

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

MAY 1969 -

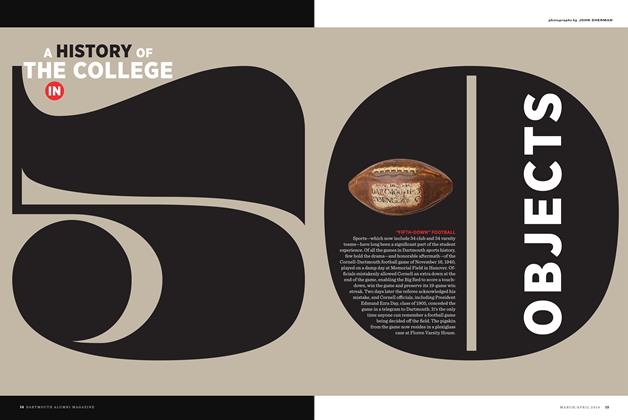

COVER STORY

COVER STORYA History of the College in 50 Objects

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

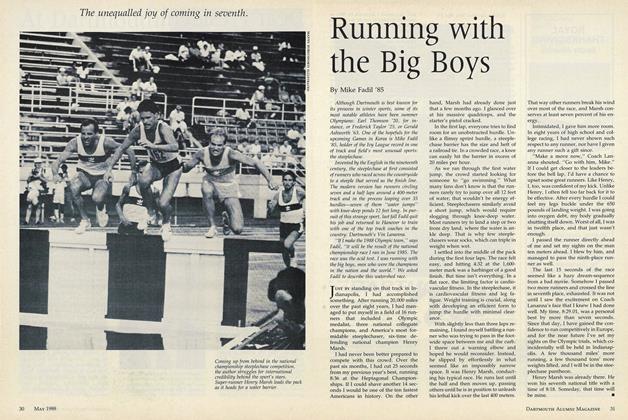

FeatureRunning with the Big Boys

MAY • 1988 By Mike Fadil '85 -

Feature

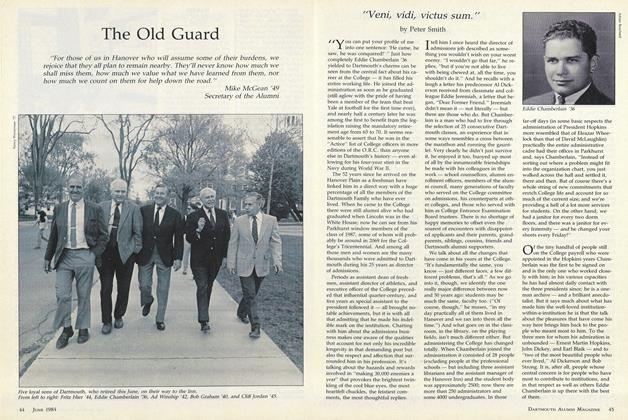

Feature"Veni, Vidi, victus sum."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith