By David J. Luck '34. Englewood Cliffs:Prentice-Hall, Inc. 118 pp. $2.95.

Consider the immense effort which goes into new products, and the futility of much of this effort—most new products fail, David Luck points out. One might expect business would formulate a set of principles for choosing and guiding new products, and back up these principles with proof and evidence. ON the contrary, the mad dance of new products in technical societies merely confuses us. With no science to guide us, we face even a "Malthusian spectre of product overpopulation," in Philip Kotler's analogy. The resulting waste has no small social and political implications.

The appearance of new competitive products often generates frantic activity from managers rather than cool analysis. It is therefore reassuring to find a few cool analysts in the field able to transmit to us their ability to view the process as a whole. In a short pithy treatise of scarcely 110 pages, Professor Luck introduces us to the fundamental concepts necessary for describing product life, outlining the options open to managers, and suggesting further readings.

The very high degree of condensation in writing made necessary a terse style, with considerable resort to lists of things. He always links these lists to his working concepts, however, and hence avoids the superficiality of the manual writer. Professor Luck frequently illustrates his concepts with rather well chosen examples from the marketing field. The heart of the book—for me—was the material on product youth and maturity. Others would find material pertinent to their interests in decisionmaking, policy formation, and, of course, product management.

Of course, no product has a life cycle in the sense that a person does, although it is a most useful analogy as he employs it. Nor can products "behave"—only people behave. But these are useful terms if employed in description, as Professor Luck does, and not used as explanations, a trap he avoids.

It is surprising that the book does not analyze services, which clearly fall within the Luck definition of products. There is a growing importance of services in our economy, and thus his concepts have a broader usefulness than shown here.

At the end of this well organized treatise we are left with the mystery of why so many products fail, but this is no worse than other mysteries in the field of marketing: R&D investment (who can forecast return?) or advertising (who knows when it is well spent?). Even though Professor Luck does not solve the mystery, he does give us some working tools for coming to decision. That at least will encourage the manager discouraged by complexity.

Adjunct Professor of Psychology and Director of Institutional Research at DartmouthCollege, Mr. Dailey has resigned to acceptthe position of Research Associate atHarvard University where he will work withDavid McClelland in the analysis of powerand also serve as Industrial Consultant onproblems of executive selection.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1972

July 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

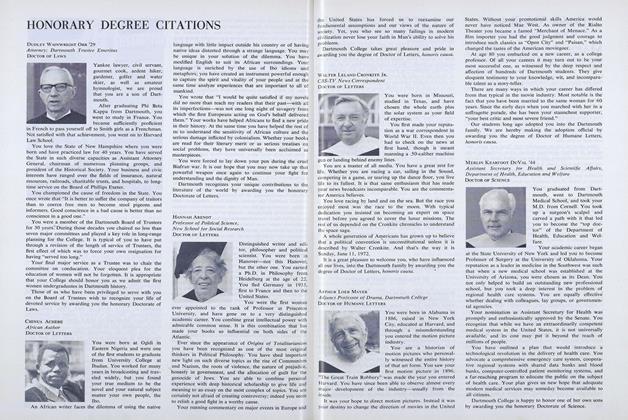

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1972 -

Feature

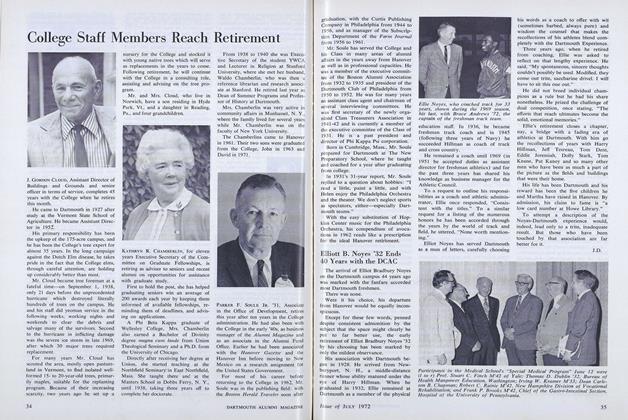

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

July 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

July 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

July 1972

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

DECEMBER 1970 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Nov/Dec 2005 -

Books

BooksHOW TO SING FOR MONEY

January 1940 By DONALD E. COBLEIGH '23 -

Books

BooksSOVIET POLICY AND THE CHINESE COMMUNISTS 1931-1946.

FEBRUARY 1959 By H. GORDON SKILLING -

Books

BooksCUBAN TAPESTRY.

December 1936 By Ralph A. Burns. -

Books

BooksPOETRY: A CLOSER LOOK

FEBRUARY 1964 By RICHARD EBERHART '26