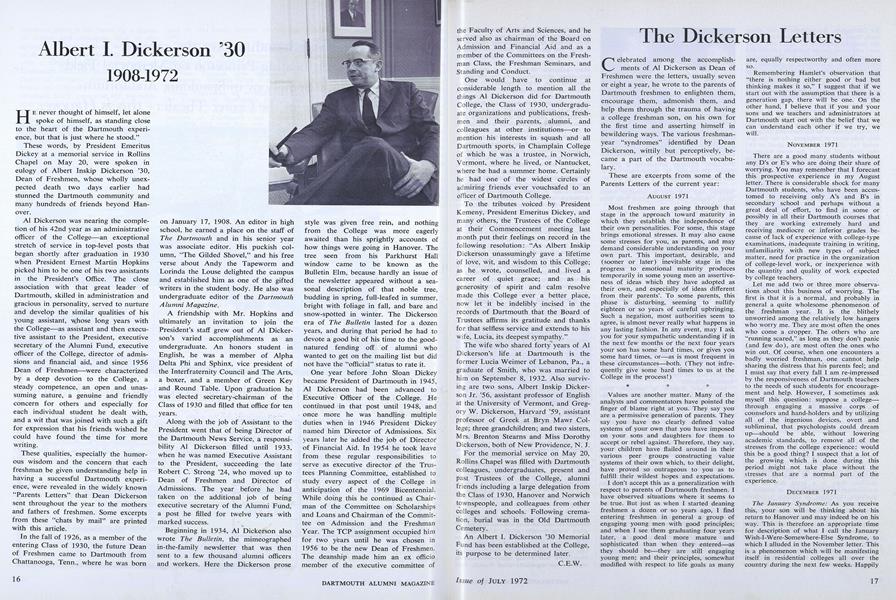

Celebrated among the accomplishments of Al Dickerson as Dean of Freshmen were the letters, usually seven or eight a year, he wrote to the parents of Dartmouth freshmen to enlighten them, encourage them, admonish them, and help them through the trauma of having a college freshman son, on his own for the first time and asserting himself in bewildering ways. The various freshmanyear "syndromes" identified by Dean Dickerson, wittily but perceptively, became a part of the Dartmouth vocabulary.

These are excerpts from some of the Parents Letters of the current year:

AUGUST 1971

Most freshmen are going through that stage in the approach toward maturity in which they establish the independence of their own personalities. For some, this stage brings emotional stresses. It may also cause some stresses for you, as parents, and may demand considerable understanding on your own part. This important, desirable, and (sooner or later) inevitable stage in the progress to emotional maturity produces temporarily in some young men an assertiveness of ideas which they have adopted as their own, and especially of ideas different from their parents'. To some parents, this phase is disturbing, seeming to nullify eighteen or so years of careful upbringing. Such a negation, most authorities seem to agree, is almost never really what happens in any lasting fashion. In any event, may I ask you for your sympathetic understanding if in the next few months or the next four years your son has some hard times, or gives you some hard times, or—as is most frequent in these circumstances—both. (They not infrequently give some hard times to us at the College in the process!)

Values are another matter. Many of the analysts and commentators have pointed the finger of blame right at you. They say you are a permissive generation of parents. They say you have no clearly defined value systems of your own that you have imposed on your sons and daughters for them to accept or rebel against. Therefore, they say, your children have flailed around in their various peer groups constructing value systems of their own which, to their delight, have proved so outrageous to you as to fulfill their wildest hopes and expectations.

I don't accept this as a generalization with respect to parents of Dartmouth freshmen. I have observed situations where it seems to be true. But just as when I started deaning freshmen a dozen or so years ago, I find entering freshmen in general a group of engaging young men with good principles; and when I see them graduating four years later, a good deal more mature and sophisticated than when they entered—as they should be—they are still engaging young men; and their principles, somewhat modified with respect to life goals as many are, squally respectworthy and often more so.

Remembering Hamlet's observation that "there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so," I suggest that if we start out with the assumption that there is a generation gap, there will be one. On the other hand, I believe that if you and your sons and we teachers and administrators at Dartmouth start out with the belief that we can understand each other if we try, we will.

NOVEMBER 1971

There are a good many students without any D's or E's who are doing their share of worrying. You may remember that I forecast this prospective experience in my August letter. There is considerable shock for many Dartmouth students, who have been accustomed to receiving only A's and B's in secondary school and perhaps without a great deal of effort, to find in some or possibly in all their Dartmouth courses that they are working extremely hard and receiving mediocre or inferior grades because of lack of experience with college-type examinations, inadequate training in writing, unfamiliarity with new types of subject matter, need for practice in the organization of college-level work, or inexperience with the quantity and quality of work expected by college teachers.

Let me add two or three more observations about this business of worrying. The first is that it is a normal, and probably in general a quite wholesome phenomenon of the freshman year. It is the blithely unworried among the relatively low hangers who worry me. They are most often the ones who come a cropper. The others who are "running scared," as long as they don't panic (and few do), are most often the ones who win out. Of course, when one encounters a badly worried freshman, one cannot help sharing the distress that his parents feel; and I must say that every fall I am re-impressed by the responsiveness of Dartmouth teachers to the needs of such students for encouragement and help. However, I sometimes ask myself this question: suppose a college—through engaging a massive corps of counselors and hand-holders and by utilizing all of the ingenious devices, overt and subliminal, that psychologists could dream up—should be able, without lowering academic standards, to remove all of the stresses from the college experience: would this be a good thing? I suspect that a lot of the growing which is done during this period might not take place without the stresses that are a normal part of the experience.

DECEMBER 1971

The January Syndrome: As you receive this, your son will be thinking about his return to Hanover and may indeed be on his way. This is therefore an appropriate time for description of what I call the January Wish-I-Were-Somewhere-Else Syndrome, to which I alluded in the November letter. This is a phenomenon which will be manifesting itself in residential colleges all over the country during the next few weeks. Happily for Dartmouth, the calendar of our threeterm, three-course program removes one of the main elements of the syndrome. Your son came home for the holidays with his first college finals under his belt. They weren't anywhere near as traumatic an experience as the sophomores had made him believe. The fact that these first finals are now behind him, for better or for worse, gives the Dartmouth freshman a welcome feeling of relief and of belonging.

But speaking generally, the campus-bound freshman as January approaches is not a happy man. Home had never looked so good to him. You were never so liberal with the keys to the car. The brothers and sisters, if any, were never so indulgent. As for the girl, either (a) she never looked so good, or (b) they broke off, or (c) the worst happened and both of these things occurred. (The latter is known as being "shot down.") None of these three eventualities tends to cheer the student in January as he sets off to return to his college campus. The sense of adventure and discovery which dominated the September departure is missing. In its place is a sort of delayed homesickness. So . . . the freshman, having vastly enjoyed the all-too-brief hometown exhilaration of being The Returned College Man, goes back to college to face, under most college calendars, the culmination of all his academic insecurities as the dreaded finals approach. Even the Dartmouth freshman, with that particular ordeal behind him, turns his face toward Hanover with a sobering sense of still having his way to make as a college man.

So in January in residential colleges everywhere, freshman deans are talking to freshmen who come in to say they think they should quit college, or transfer; go to work, or join the army, or travel. They talk about their health, their sinuses, the climate; about your health or business problems, or the illness of aunts or grandparents; they yearn for the life of the big city (whether or not they have ever lived on one); they have suddenly discovered that a college nearer home (where possibly a particular girl happens to be attending or planning to enroll) offers courses especially well adapted to their suddenly discovered needs; etc., etc. Things they never mention are (a) homesickness and (b) worry over finals.

For this description of the January Wish-I-Were-Somewhere-Else Syndrome, I have drawn on various colleagues at other colleges. It's a comfort to all of us to realize how universal this experience is.

Let's face it: a college freshman is likely to be a pretty self-centered fellow. At the freshman's age and in this once-in-a-lifetime situation of feeling that one must make his place quickly in a new peer group of substantial size and of high and varied abilities, there is a great deal of selfquestioning; of self-evaluation in relation to academic challenges, in relation to fellowstudents, in relation to girls, in relation to everything. In simple fact, freshmen spend a lot of time thinking about themselves. It is understandable if parents, in the face of this sometimes massive self-preoccupation, occasionally feel rebuffed. It is an odd but widely recognized fact that it never occurs to young men of this age, who are themselves extremely sensitive to criticism from their families, that parents also have feelings, and can also be sensitive about being "wanted" or being treated with bare toleration.

Some of you have observed, usually with more amusement than irritation, exaggerated assertions of independence by word or deed by these young men who know as well as you do (hence the instinct to assertiveness) their degree of continuing dependence in more than just the financial sense. If some of your freshman sons seem to have all the answers, I can only warn: wait until they are sophomores!

MARCH 1972

The Schlump Syndrome: Now for a look at the Schlump (or "Let's-Get-the-Heck-Out-of Here") Syndrome, mostly for fun.... The symptoms begin to appear in the latter half of February. It is then that the term's second flurry of hour exams occurs, term papers come due, the spectre of finals begins to loom over the horizon, and the end-of-term pressures begin to build up. For some reason these pressures are more apparent during the winter term than during the fall, possibly because they are accentuated by the onset of schlump.

Here let's disgress a moment from schlump to identify some differences between the troubled ones of the winter term and those of the fall term, differences which have nothing to do with weather. Let's take Hal Ramsey, as a characteristic example of winter term discouragement. Hal, like so many, is a serious and highly motivated student. Like so many, he got high grades in high school. Like so many, he had rough sledding in the fall term. However, people had told him that it would be like this and so he wasn't unduly discouraged. He wound up that term with a 1.7 and an academic warning, so he buckled down to work even harder during the winter. He gave up all of the fun things, cut out the last bits of timewasting, and booked and booked. He was interested in his courses. But again, at winter mid-term he found himself with a D and an E. By this time he was pretty depressed. His letters home became increasingly despondent. He was taking reading and study skills programs and learning useful things, but would he master these in time to be saved? He had clutched in a fall-term French final. Would he do it again? He was doing everything that he could to succeed. What could a dean tell him? Not much more than to be of good heart, keep trying, relax, have a little fun, get enough sleep and exercise, and be confident that his combination of high motivation, interest in his work, more than adequate abilities, and developing experience with college work would result, sooner or later, in higher grades.... Hal is typical of a great many of the troubled people of the winter term. Most of those in Hal's category will begin to find their rewards in the spring term.

Now let's return to the Schlump Syndrome, whose phenomenology is very similar to that previously described for the January Wish-I-Were-Somewhere-Else Syndrome. Its peculiar characteristic is its contagiousness. It spreads through roommates, corridors, dormitories. It has a curious way of infecting students who come from the same schools or home towns. Take, as an example of the galloping contagion of this odd affliction, the Beston Case. Leslie Eeston (pseudonym) came from a suburb north of Chicago. Although his was a January case, his symptoms differed from those of the January Syndrome, whose sufferers by and large are afflicted by the normal frustrations of the freshman struggle for academic and social recognition. Beston had earned a fall-term 3.7 (which then put him in the top quarter) while being a prominent member of the freshman football team. He had won considerable recognition. But, he said, he had to work so hard doing it that life just wasn't worth the candle. So off he went in January to a mid-western university "where you don't have to work so hard"—(and where there are GIRLS).

Come Schlump that year, we began to run into a series of cases of this special virus, which we began to trace back to Beston. Eventual research proved that a large number of these sufferers had been infected by a non-filterable, itchy virus which became known as the "Beston Strain." The geographical origins of the sufferers showed a heavy concentration around Chicago, and it was eventually found that the infection had raged through the North Shore suburbs all the way to Palatine. (Practically all recovered.) Such infections have also been found to spread from campus to campus: certain restless strains have been traced to New Haven, Williamstown, Cambridge, and elsewhere, and it was later reported that the Beston Strain had infected some of his friends at Williams and Yale.

Another example of the curious communicability of the Schlump Syndrome comes to mind. John Armstrong and George Sanders attended the same country day school in, say, Pennsylvania. On February 27 in that year, John Armstrong came in. He had been looking into the University of Accra in Ghana. He was going home that weekend and wanted to discuss a leave of absence next year, to be spent probably in Ghana.... Late in the afternoon of the same day, George Sanders came in. He'd been looking into the Army's six-month deal and was considering a leave of absence for military service. He also let drop the fact that he had given some thought to the University of Accra in Ghana ... Accra twice in the same day. And the Hillcrest Country Day School. One couldn't help putting 2 and 2 together. Here were two young men not rooming together, not especially close friends, both doing well academically, both intellectually curious and interested in their courses, both appearing to have outside interests and satisfactory circles of friends and not the slightest indication of (if you'll pardon the expression) poor "adjustment."

Armstrong (he who discovered Ghana's University of Accra) was in again just before the spring recess. He was now thinking about military service ... And how about Sanders? Well, you've guessed it. Sanders was now gung-ho about Ghana.

Throughout the spring term, the Armstrong-Sanders strain kept cropping up among their acquaintances. This was unusual, since there aren't many spring syndromes. Withdrawal symptoms tend to disappear as the elms begin to bud.

So you will begin to get the picture of the Schlump Syndrome. I shall now come clean and admit that I have purposely concealed, up to now, the symptomatology of Schlump. I try, in general, to tip you off in advance to the up-and-down curves of freshman morale. But the communicability of the Schlump Syndrome has held me back for fear of increasing the incidence of these diseases simply by talking about them.

Any catalogue of syndromes should include the California Syndrome. Sufferers from this syndrome don't really suffer—often they are very happy at Dartmouth. It's just that, after a while, continued separation from that Garden of Eden on the west coast seems hardly endurable. Similar symptom patterns are sometimes observed in Texans.

Considering the variety of afflictions to which undergraduates are susceptible—including academic catastrophe and severe illness—it is perhaps surprising and reassuring that 787 of the 811 '75's who arrived in September are, as of this writing, still on board.

MAY 1972

As I look back at this time of year on this series of Parents Letters, I have the feeling that they have been unduly preoccupied with problems and worries, in the effort to put the former in perspective, to allay the latter, and to dissipate the numerous anxieties which have no real foundation at all. We have joked in previous letters about your sons' reports of high endeavor and cerebral derring-do, but these freshmen have worked. And they've grown. We see it every day in talking to men whom we have seen earlier in the year.

We usually manage to invite most of the freshmen in during the year for conferences on their progress and plans—except for those we have talked with during the year in the Dining Hall, Dick's House, or elsewhere outside the office. Normally, all but a few dozen get in before the June finals. And normally, the freshmen one meets in May tend to be a happy lot. If they have had problems earlier, they have usually solved them by now; and if they have had their worries or discontents, by this time these have gone away. The May freshman is a maturer and more confident fellow than the October freshman—more confident but at the same time having more humility; more critical and at the same time more tolerant; more aware; and we think, a little wiser. He is interested in his work and looking ahead, often with impressive resourcefulness and foresight. He has struck out into one or more extra-classroom enterprises.

I don't know how familiar you are with the geography of Hanover. Just behind our office is Massachusetts Lane, which runs along the Massachusetts row of dormitories to Thayer Hall; and we park our cars in an area behind the Massachusetts Row dormitories. In the morning and at noon and frequently in the evening, we meet students on the way to and from their meals in Thayer. In the morning they're in a hurry, and travel in ones and twos, frequently on the run: The other times at this season they are in leisurely groups. The groups get bigger as the year wears on, from the fall when they travel briskly in pairs in animated conversations about campus, to the spring when they move in squads and platoons, often with horseplay. The springtime pace is one of confidence and ease. Among the groups one may spot a gaily clowning character who was in the office last winter talking somberly about transferring to Harvard or Pomona, or to Hometown U. near family and/or girl. The individuals are large and small, introverted and extroverted, gay and sober, natty and sloppy, shaven and stubbled; long-haired and short-haired and "medium"; sometimes mustached and/or bearded, and frequently side-burned to the jowls. There is a great variety here, which does not fit into anyone's stereotype of the "college boy." But watching these groups in the perspective of these closing weeks of the term, one gets a renewed sense not only of the wonderful diversity of Dartmouth undergraduates but also of the pervasive quality of a Dartmouth class as it is about to move into its upperclass years.

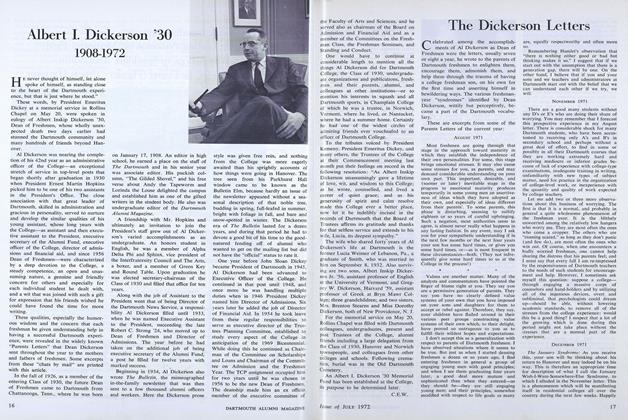

President Kemeny presenting a gift toDean Dickerson in September 1970,marking his 40 years as a College officer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1972

July 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1972 -

Feature

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

July 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

July 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

July 1972

Article

-

Article

ArticleSOUTHERN STATES

January 1924 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for –

SEPT. 1977 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Award: William Jester Montgomery '52

December 1992 -

Article

ArticleWHERE ARE THE SONGS OF YESTERYEAR?

January 1936 By Donald E. Cobleigh '23 -

Article

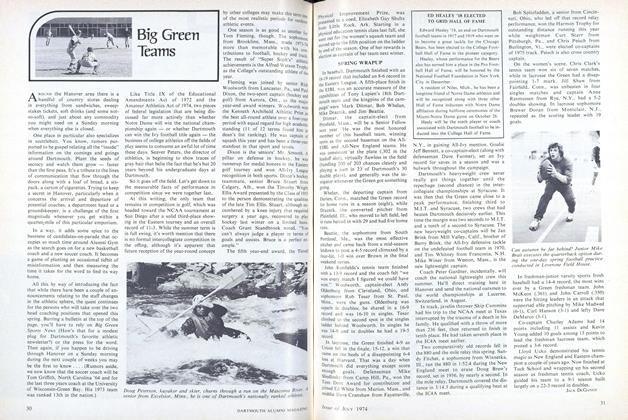

ArticleBig Green Teams

July 1974 By JACK DEGANGE