By John G. Gazley (Professor of History, Emeritus). Philadelphia: AmericaPhilosophical Society, 1973. 727 pp. With 23 illustrations and 3 maps. $10.

England's great agricultural publicist, Arthur Young, sent his first work to the press in 1758 and his last in 1817. In between those dates he published 49 other works, edited for 31 years the Annalsof Agriculture, and served as secretary for 25 years of the Board of Agriculture. During those same 59 years England experienced an Industrial Revolution, the French Revolution and its wars,a religious revival, and a population increase from 6½ to 12 million: all events involving profound changes.

Yet to Arthur Young none was so profound as the Agricultural Revolution which occurred at the same time. Of what importance to England's additional 5½ million were evangelical tracts and news from Paris compared to quantities of cheap bread! Of what importance was King Cotton compared to Scientific Agriculture! King Cotton employed some 200,000 in 1817, agriculture some million and a half. The food for England's burgeoning population came far more from the increased productivity of her fields than from the export of cotton. Perhaps no other change between 1759 and 1817 brought more benefits to more Englishmen than the Agricultural Revolution.

In that Revolution few men played a more important role than Arthur Young. He was its great disseminator. With unbound enthusiasm he reported on the discoveries of its leading "experimenters": of Bakewell, the scientific breeder of Tull, the apostle of seeding by drill; and of Townsend, the advocate of turnips. In his voluminous writings and endless travels Young lectured the English farmer on these advances, Don't let a wheat field lie fallow, he told them: a turnip crop will refresh it. The turnips will in turn feed cattle in the winter, the cattle will produce manure, and manure does wonders for the fields. And if the turnip-fed cattle are bred by Bakewell's methods, what an increase in joints of beef! use wastelands if only for grazing, enclose the commons, drain and fertilize them, and give some to the poor. On and on he went, explaining, exhorting, and preaching the gospel of scientific agriculture. It was a role that he carried out with such vigor and such skill that he may well be that Revolution's most important figure, and thereby, for those millions for whom a better life meant more bread and cheese, one of the greatest benefactors of his age. Yet not until 1973 has he been the subject of a definitive biography '

It is Arthur Young's good fortune that John Gazley has ended this scandalous lacuna. Professor Gazley, whose lectures in history at Dartmouth College delighted, for nearly 40 years, hundreds of undergraduates, has since "1931 applied a similar number of years to a definitive study of this great agriculturalist. It is a master magnus opus, one that would have delighted Arthur Young himself. It has indeed many of the same virtues that distinguish Young's Tour ofIreland and Travels in France: lively curiosity, industrious research, close observation, a conscientious regard for accuracy, richness of detail, a spacious and leisurely pace, a critical honesty, a lively, direct, and always clear style, and beneath it all a quiet charm and a puckish humor.

Both Young and Gazley are tour guides par excellence. They lead the reader through fascinating and complex worlds rather than imposing on him rigid formulations. They eschew the theoretical and the abstract and value the concrete and the immediate. Both are at heart Baconians: they let the facts speak for themselves. That facts do such, of course, is considered naive these days. But is it so naive? Mere factual reporting, to be sure, involves more arranging than meets the eye, a fact definitely true of the tours of Gazley and Young, tours in which a clear though unobstrusive artfulness lies behind a seeming artlessness of reporting. But they still do, as far as possible, let the facts speak for themselves, do allow contemporaries to speak fully and frequently, and do wisely avoid distorting the past by dressing up doubtful speculations as theories. The result is to recreate for the reader the very texture of the life of those times, whether it is the odors and dampness of a cottar's hovel or Young's despondencies over a French Revolution gone wrong or despairs over the death of his young daughter. That death led Young to evangelicalism just as it was a revolution gone wrong that turned him from a radical critic of the French Monarchy to a reactionary critic of all English reformers. In explaining these conversions John Gazley avoids the psycho-analytical guessing game so popular with today's psycho-historians. Instead, with the sensitivity to fact of a true Baconian, he cites Young's letters, the letters of Young's friends, and the day-to-day events that surrounded his conversions. The result is a rich and suggestive mosaic not only of Young's mind but also of the society in which he lived. Young was more than agriculture's great disseminator; he was also England's most popular travel writer, a political and economic controversialist, a busy, travelling, letter-writing man of the world; and in his old age a penitent of the spiritual world too. Gazley's tour of Young's life is thus a tour of the main avenues and myriad byways of late Georgian England, a tour informed throughout by a lightly held erudition, a sure shrewdness, an amiable urbanity, and an unaffected love of his subject. The fruit of 40 years research and reflection, it has recreated the life of a man who may well have benefitted his age more than any of its prime ministers, philosophers, or poets.

Dartmouth Professor of History, Mr. Robetsteaches courses in 20th-century England, Tudorand Stuart England, and HistoriographyProblems of History.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturemAgnA CARTA: Seventh Crisis of John Plantagenet

November 1973 By CHARLES T. WOOD -

Feature

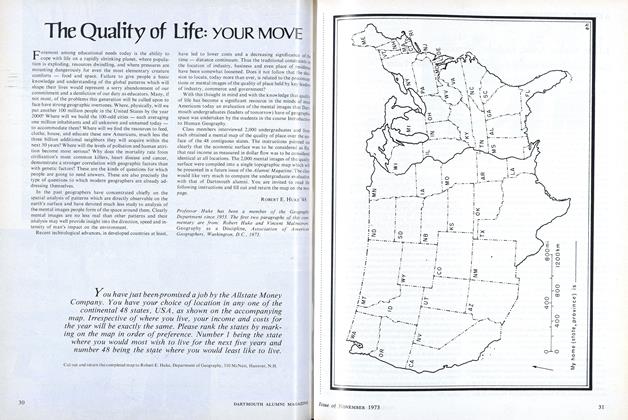

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

November 1973 By ROBERT E. HUKE'48 -

Feature

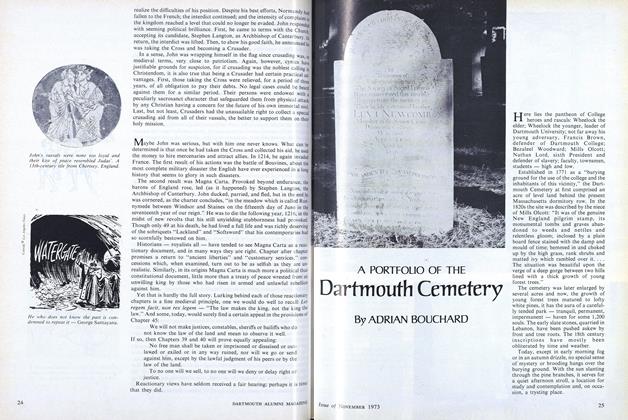

FeatureA PORTFOLIO OF THE Dartmouth Cemetery

November 1973 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

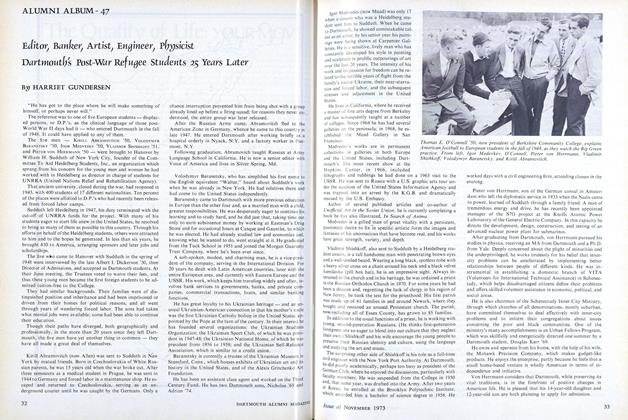

ArticleEditor, Banker, Artist, Engineer, Physicist Dartmouth's Post-War Refugee Students 25 Years Later

November 1973 By HARRIET GUNDERSEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTG.OMERY, C. HALL COLTON

DAVID ROBERTS

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY NOTES

MAY 1927 -

Books

BooksRecord Completed

March 1980 By Charles M. Wiltse -

Books

BooksSPEECH-MAKING

December 1938 By Dayton D. McKean. -

Books

BooksVASSI AND FIDELES IN THE CAROLING

August 1945 By John R. Williams '19 -

Books

BooksSHOTS HEARD ROUND THE WORLD.

January 1958 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Books

BooksADVENTURES IN WORLD LITERATURE.

June 1937 By Stearns Morse