Editor, Banker, Artist, Engineer, Physicist Dartmouth's Post-War Refugee Students 25 Years Later

November 1973 HARRIET GUNDERSENEditor, Banker, Artist, Engineer, Physicist Dartmouth's Post-War Refugee Students 25 Years Later HARRIET GUNDERSEN November 1973

"He has got to the place where he will make something of himself, or perhaps never will."

The reference was to one of five European students - displaced persons, or D.P.'s, as the clinical language of those post-World War II days had it - who entered Dartmouth in the fall of 1948. It could have applied to any of them.

The five men - KIRILL ABRAMOVITCH '50, VOLODYMYR BARANETSKY '50, IGOR MEDVEDEV '5O, VLADIMIR SHISHKOFF '51, and PIETER VON HERRMANN '50 - were brought to Hanover by William H. Sudduth of New York City, founder of the Committee To Aid Heidelberg Students, Inc., an organization which sprang from his concern for the young men and women he had worked with in Heidelberg as director in charge of students for UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency).

That ancient university, closed during the war, had reopened in 1945, with 400 students of 17 different nationalities. Ten percent of the places were allotted to D.P.'s who had recently been released from forced labor camps.

Sudduth left Heidelberg in 1947, his duty terminated with the cut-off of UNRRA funds for the project. With many of his students eager to start life anew in the United States, he resolved to bring as many of them as possible to this country. Through his efforts on behalf of the Heidelberg students, others were attracted to him and to the hopes he generated. In less than six years, he brought 450 to America, arranging sponsors and later jobs and scholarships.

The five who came to Hanover with Sudduth in the spring of 1948 were interviewed by the late Albert I. Dickerson '30, then Director of Admissions, and accepted as Dartmouth students. At their June meeting, the Trustees voted to waive their fees, and thus these young men became the first foreign students to be admitted tuition-free to the College.

They had similar backgrounds. Their families were of distinguished position and inheritance and had been imprisoned or driven from their homes for political reasons, and all went through years of wandering forced labor. The sons had taken what menial jobs were available; some had been able to continue their education.

Though their paths have diverged, both geographically and professionally, in the more than 20 years since they left Dartmouth, the five men have yet another thing in common - they have all made a great deal of themselves.

Kirill Abramovitch (now Allen) was sent to Sudduth in New York by mutual friends. Born in Czechoslovakia of White Russian parents, he was 15 years old when the war broke out. After three semesters as a medical student in Prague, he was sent in 1944 to Germany and forced labor in a maintenance shop. He escaped and returned to Czechoslovakia, serving as an underground courier until he was caught by the Germans. Only a chance interruption prevented him from being shot with a group already lined up before a firing squad; for reasons they never understood, the entire group was later released.

After the Russian Army came, Abramovitch fled to the American Zone in Germany, whence he came to this country in late 1947. He entered Dartmouth after working briefly as a hospital orderly in Nyack, N.Y. and a factory worker in Piermont, N.Y.

Following graduation, Abramovich taught Russian at Army Language School in California. He is now a senior editor with Voice of America and lives in Silver Spring, Md.

Volodymyr Baranetsky, who has simplified his first name to the English equivalent "Walter," heard about Sudduth's work when he was already in New York. He had relatives there and had come to the United States independently.

Baranetsky came to Dartmouth with more previous education in Europe than the other four and, as a married man with a child, greater responsibilities. He was desperately eager to continue his learning and to study hard, and he did just that, taking time out only to earn subsistence money by working at Eastman's Drug Store and for occasional hours at Casque and Gauntlet, to which he was elected. He had already studied law and economics and, knowing what he wanted to do, went straight at it. He graduated from the Tuck School in 1951 and joined the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company, where he's been ever since.

A soft-spoken, modest, and charming man, he is a vice president of the company, serving in the International Division. For 20 years he dealt with Latin American countries, later with the entire European area, and currently with Eastern Europe and the USSR. His work, which keeps him traveling widely and often, involves bank services to governments, banks, and private companies, commercial transactions, loans, and similar banking functions.

He has great loyalty to his Ukrainian heritage - and an unusual Ukrainian-American connection in that his mother's uncle was the first Ukrainian Catholic bishop in the United States, appointed by the Pope at the turn of the century. In their interest he has founded several organizations: the Ukrainian Students Organization; the Ukrainian Sport Club, of which he was president in 1947-48; the Ukrainian National Home, of which he was president from 1956 to 1958; and the Ukrainian Self-Reliance Association, which is similar to a credit union.

Baranetsky is currently a trustee of the Ukrainian Museum in Stamford, Conn., which houses exhibits of Ukrainian art and its history in the United States, and of the Alexis Gritchenko Art Foundation.

He has been an assistant class agent and worked on the Third Century Fund. He has two Dartmouth sons, Nicholas '69 and Adrian '74.

Igor Medvedev (now Mead) was only 17 when a cousin who was a Heidelberg stujent sent him to Sudduth. When he came to Dartmouth, he showed unmistakable talent as an artist; by his senior year his paintings were being shown at Carpenter Galleries. He is a sensitive, lively man who has constantly developed his style in painting and sculpture in prolific outpourings of art over the last 20 years. The intensity of his work and its passion for freedom can be related to the terrible years of flight from the family's native Ukraine, their near-starvation and forced labor, and the subsequent stresses and adjustment in the United States.

He lives in California, where he received a master of fine arts degree from Berkeley and has subsequently taught at a number of colleges. Since 1964 he has had several galleries on the peninsula; in 1968, he established the Mead Gallery in San Francisco.

Medvedev's works are in permanent collections in galleries in both Europe and the United States, including Dartmouth's. His most recent show at the Hopkins Center, in 1966, included lithographs and rubbings he had done on a 1963 visit to the USSR. He was sent to Russia with a U.S. graphic arts tour under the auspices of the United States Information Agency and was trapped into an arrest by the K.G.B. and dramatically rescued by the U.S. Embassy.

Author of several published articles and co-author of Unofficial Art in the Soviet Union, he is currently completing a book he has also illustrated, In Search of Anima.

Medvedev is a gifted man of great vitality with a persistent, passionate desire to fix in specific artistic form the images and fantasies of his unconscious that have become real, and his works have great strength, variety, and depth.

Vladimir Shishkoff, also sent to Sudduth by a Heidelberg student cousin, is a tall handsome man with penetrating brown eyes and a well-tended beard. Wearing a long black, spotless robe with a heavy silver cross on a chain around his neck and a black velvet kamilavka (pill box hat), he is an impressive sight. Always interested in the church and in his heritage, he was ordained a priest in the Russian Orthodox Church in 1970. For some years he had been a deacon and, regretting the lack of clergy in his region of New Jersey, he took the test for the priesthood. His first parish was made up of 41 families in and around Newark, where they bought and restored an unused Protestant church. The parish, now including all of Essex County, has grown to 85 families.

In addition to the usual functions of a priest, he is working with young, second-generation Russians. (He thinks first-generation foreigners are so eager to blend into our culture that they neglect their own.) Shishkoff and his wife encourage the young people to preserve their Russian identity and culture, using the language and studying the art and music.

The surprising other side of Shishkoff is his role as a full-time civil engineer with the New York Port Authority. At Dartmouth, he did poorly academically, perhaps too busy as president of the German Club, where he enjoyed the discussions, particularly with faculty members. He was suspended from the College in 1950 and, that same year, was drafted into the Army. After two years in Korea, he enrolled at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, which awarded him a bachelor of science degree in 1958. He worked days with a civil engineering firm, attending classes in the evening.

Pieter von Herrmann, son of the German consul in Amsterdam who left the diplomatic service in 1933 when the Nazis came to power, learned of Sudduth through a family friend. A man of tremendous energy and drive, he has recently been appointed manager of the S7G project at the Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory of the General Electric Company. In this capacity he directs the development, design, construction, and testing of an advanced nuclear power plant for submarines.

After graduating from Dartmouth, von Herrmann pursued his studies in physics, receiving an MA from Dartmouth and a Ph.D. from Yale. Deeply concerned about the plight of minorities and the underprivileged, he works tirelessly for his belief that inner-city problems can be ameliorated by implementing better relationships between people of different kinds. He was instrumental in establishing a domestic branch of VITA (Volunteers for International Technical Assistance) in Schenectady, which helps disadvantaged citizens define their problems and offers skilled volunteer assistance in economic, political, and social areas.

He is also chairman of the Schenectady Inner City Ministry, through which churches of all denominations, mostly suburban, have committed themselves to deal effectively with inner-city problems and to inform their congregations about issues concerning the poor and black communities. One of the ministry's many accomplishments is an Urban Fellows Program, which was skillfully and energetically directed one summer by a Dartmouth student, Douglas Kerr '69.

He owns and operates from his home, with the help of his wife, the Mohawk Precision Company, which makes gadget-like products. He enjoys the enterprise, partly because he feels that a small home-based venture is wholly American in terms of independence and initiative.

Von Herrmann considers that Dartmouth, while preserving its vital traditions, is in the forefront of positive changes in American life. He is pleased that his 14-year-old daughter and 12-year-old son are both planning to apply for admission.

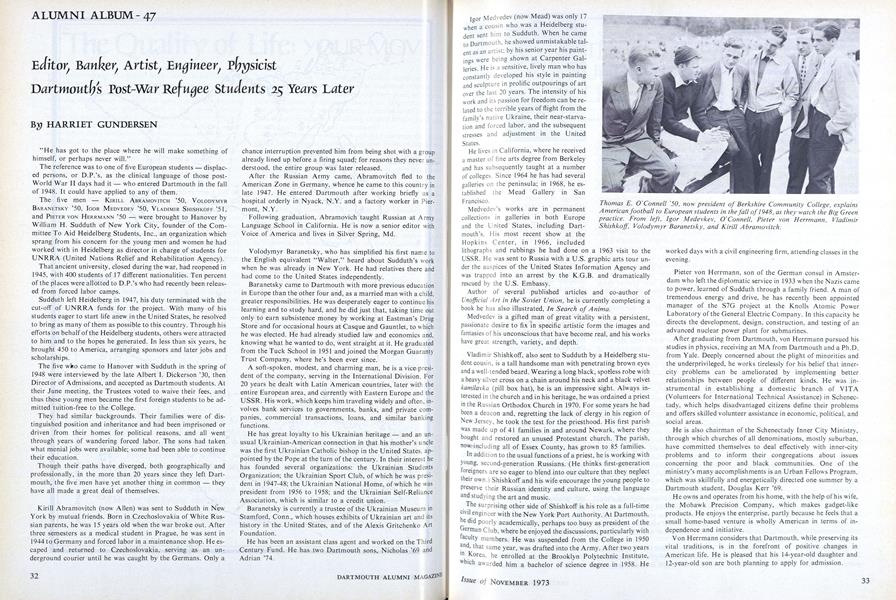

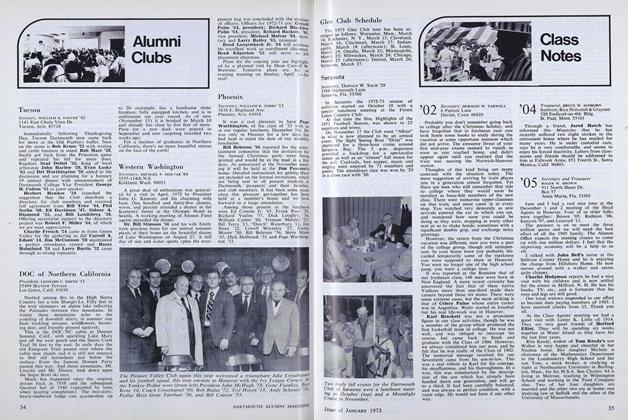

Thomas E. O'Connell '50, now president of Berkshire Community College, explainsAmerican football to European students in the fall of 1948, as they watch the Big Greenpractice. From left, Igor Medevkev, O'Connell, Pieter von Herrmann, VladimirShishkoff, Volodymyr Baranetsky, and Kirill Abramovitch.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturemAgnA CARTA: Seventh Crisis of John Plantagenet

November 1973 By CHARLES T. WOOD -

Feature

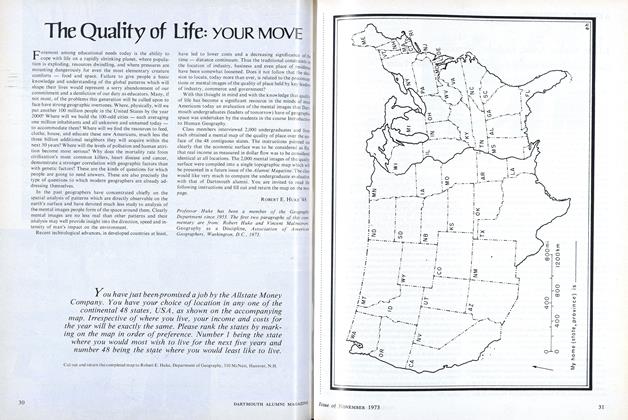

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

November 1973 By ROBERT E. HUKE'48 -

Feature

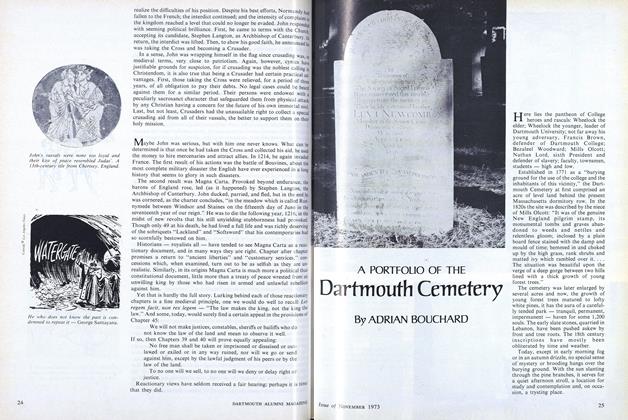

FeatureA PORTFOLIO OF THE Dartmouth Cemetery

November 1973 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTG.OMERY, C. HALL COLTON -

Article

ArticleTHE FBI AND ME or, How I Didn't Shoot Eisenhower

November 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING'25