This article has been adapted from a lecture given during the 1973 Alumni College,which had an overall theme of "Law: WhoNeeds It?" Professor Wood, AcademicDirector of the Alumni College and, since1964, a member of the History Department, has known his own seven (or dozen?,or two dozen?) crises as the embattledchairman of the Hanover - NorwichSchool Board.

Only yesterday, it seems, most people judged History a dying subject: old-fashioned, irrelevant, boring. Now, however, different attitudes prevail. Reporters discourse learnedly on Chief Justice Marshall and Thomas Jefferson, while before his resignation Vice President Agnew appears to have acquired an amazingly extensive knowledge of relations between Congress and Vice President Calhoun in 1826. Thus do constitutional crises make historians of us all.

Given this turn of events, possibly it would be instructive to push the clock even further back, to examine the origins and purpose of Magna Carta, first of our constitutional documents and foundation stone of all our liberties. Yet to do so is difficult. In John Ehrlichman's fine phrase, many of its provisions have been "considerably eroded over the years" - so much so that even their meaning has become obscure. Nevertheless, the historical circumstances surrounding this charter are revealing, and they do much to bring its point more clearly into focus.

To see those circumstances, we cannot begin with the England of 1215. Rather, we must return to the realm William had conquered a century and a half before: peaceful, isolated, rural, agricultural, and surprisingly untouched by the hand of man. Vast stretches of countryside were trackless waste, dense forest, or undulating moor and plain.

England then had little need for central government. Such state powers as existed were largely exercised at the local level, by royal sheriff or manorial lord, and the laws were customary - no more than traditional ways of handling problems which the people themselves had developed over the years. From our point of view judicial procedures were a bit rough and ready, involving superstitious ordeals and savage penalties, but it was the people themselves who sat in judgment, taking community responsibility into their own hands. The harshness we see went unnoticed at the time.

Yet England was not destined to remain rural and isolated. The 12th century proved a time of rapid change. New technology raised crop yields; population soared; and as it did, thousands left their ancestral homes to become pioneers, putting the plow to the wilderness and pushing outwards the frontiers of settlement. This was also an age of rapid urbanization. Cities mushroomed overnight; trade and manufactures flourished; and England abandoned her island isolation. From 1154 her king, Henry II (husband of Eleanor of Aquitaine), ruled almost half of France, and with the accession of Richard the Lion-Hearted came the Crusades, idealistic if savage wars in the East, designed to liberate and safeguard these lands from the foreign and unchristian beliefs of those who happened to live there.

Under these changed conditions, local government no longer sufficed From the beginning of the 12th century, but more especially from the accession of Henry II, one sees the growth of central government - of departments, of paperwork, of bureaucracy - all needed to meet the demands to which this rapidly growing and changing society had given rise. Royal justice, dispensed by royal justices, supplanted that dispensed by the folk in their hundreds and shires. Ever increasing obligations were imposed to meet the increased costs of government, notably of a military which was becoming increasingly professionalized and whose new weaponry was becoming more and more expensive. It seemed as though the king was impinging on more and more aspects of life.

The people did not object. If they lost some say about the way they were ruled, they gained efficiency and greater assurance that their needs would be met rapidly and with an externalized impartiality impossible to achieve under local control. Besides, royal justice was rational. Unlike the superstitious ordeals that preceded Henry II's assizes, royal justice depended on testimony and evidence. And how much better Henry's grand and petit juries appeared than the procedural morass they replaced.

As for people of consequence (as the British like to call them) - the knights, barons and earls of the realm - they, too, saw little reason to complain. They had lost some of their local powers, but replacing them had come opportunities for advancement in the central government; chances to gain fame and fortune in military adventure overseas; and a continuing right to provide aid and counsel to the king as he strove to shape policy and administer the kingdom.

Still, when one looks back at these events, it seems clear that trouble must have been brewing for some time, at least from the reign of Henry II. But no one noticed until the accession of John. Part of the trouble lay with his personality, one that historians have seen as dark, suspicious, moody, and secretive. By no means the extrovert, he was given to wild changes in temper and policy. Frenetic action, incompletely considered, could be followed by weeks and months in which he would suddenly withdraw to brood and meditate, totally out of the sight of his subjects.

John has posed a dilemma for historians. His talents were undisputed, even in his own day. His courage was beyond question. People cited, for example, the cool fortitude with which in his youth he resisted foreign mobs in France who threatened to attack and kill him when he, alone of Henry II's sons, remained true to his father while the others rose in revolt.

On the other hand, he was sly, devious, and overly ambitious. When Richard had been captured and held to ransom on his way home from the Crusades, John's regency was hardly a success. The legends of Robin Hood and Sherwood Forest, of all the good people of England banding together to raise the money needed to free their sovereign lord, are scarcely accurate historically, but they do speak to a higher truth about the feelings of dread and mistrust John engendered.

His rise to the kingship hardly inspired confidence. Richard died childless in 1199, but his next younger brother Geoffrey had predeceased him, leaving a young son Arthur. In terms of legitimate hereditary succession, Arthur was clearly Richard's heir, but John, at 32 the youngest of the late king's brothers, succeeded in excluding him. When others protested, John bought them off, notably Philip Augustus, King of France, to whom he did not hesitate to pay 20,000 marks, roughly the equivalent of one year's revenue for the total realm of England. When support for Arthur continued, John simply had him seized and imprisoned, never to know freedom again. Most accounts agree he was starved to death.

Still, there were hopes with John, mainly in international affairs. Since Henry II's day, England had been mired in foreign war. The king's cross-Channel fiefs, notably Normandy, had attracted the covetous eye of the king of Franee, and for forty years and more the two sides had struggled endlessly of control. During the last eight or nine years these battles had reached a crescendo. Richard loved war, and Philip Augustus gave it to him.

Everything suggests, however, that by 1199 England was getting War-weary, and to those tired of carnage and strife, John offered hope. He had plan for peace, he said, and he attempted to pass off all the bribes he had paid to gain the throne, notably the 20,000 marks to Philip Augustus, as steps necessary to insure the friendship of potential opponents. Nevertheless as things turned out, peace was not at hand, and all because of John's stupidity - or, really, his willingness to exceed all bounds in the pursuit of his objectives. For example, Arthur's murder did not sit well with the French court, and in 1202 there came an opportunity to do something about it when John developed (of all things) marital problems.

John's fiefs in France consisted of two large blocs: Aquitaine in the South and Normandy, Anjou, and Poitou to the North. They lacked any land communication between them. In 1200 John found a solution, a way of joining these lands together with a bridge of new acquisitions. This he did by marrying Isabella, heiress to the county of Angouleme, a fief that would provide the final link between his disjointed possessions.

The only difficulty with this arrangement was that at the time of John's courtship, Isabella was already engaged: to Hugh the Brown, count of neighboring La Marche, and a vassal of John. Hugh was understandably distressed by what had happened. He appears genuinely to have loved the lady (he married her after John's death) and, besides, Angouleme lay next to La Marche, so if he were to acquire it, he stood some chance of increasing his own power and prestige beyond what he then enjoyed as a noble of the more-or-less middling rank.

So Hugh sued, basically for alienation of affection and resulting material damages. Unfortunately, since he was John's vassal, feudal law dictated that it was to John's court that he had to carry his case against John. Needless to say, the latter refused to hear the suit, arguing that everything he had done had been good, proper, and in the best interests of his subjects. Besides, he seems to have felt that it would be constitutionally inappropriate for him to serve as judge in his own case.

Hugh, furious, both rose in revolt and lodged an appeal with John's overlord in France, Philip Augustus. Philip was only too happy to hear the case, and in 1202 he three times cited John to appear before his court, thereto receive the judgment of his peers. John made no move except to sulk, as was his custom when hard pressed. And one understands why: Although as duke of Normandy and Aquitaine he possibly had peers, he was also king of England, and that by the grace of God. The constitutional impropriety of it all may have weighed heavily in John's mind, but when he failed to appear, Philip's court nevertheless declared him a contumacious vassal and all his lands forfeit.

Since John was not about to accept this French decision as definitive, the result was renewed war, a war much more intense than ever before because thanks to the resources provided by the 20,000-mark bribe, Philip could hire more troops and keep them better supplied and equipped. John's response was to summon the whole of the English feudal host for service in Normandy.

The situation began to unravel. When the English troops assembled, many refused to serve, arguing that while they owed support for defense of the realm, they saw no national interest involved in France. The French fiefs were John's personal property and therefore his personal problem. If difficulties had developed there, it was largely his own fault and he had no one to blame but himself. No one's honor was at stake except his, and he could very well look after it on his own.

To this refusal the Church added its voice, pronouncing the war immoral and unjust. There were no just goals, involved such as had been perceived in the Crusades. Rather, it was Christian against Christian for no noticeable cause much higher than greed. The Church forbade all Christians to participate on either side, proclaiming that anyone who served would be guilty of mortal sin, especially should he happen to kill someone in battle. In the absence of justification, that would be no less than murder.

To give John credit, he was nothing if not stubborn. Angered by the opposition he was receiving, he pressed on, believing (and not unreasonably) that some people were out to get him, no matter what he did. Further, he resented the fact that he was not receiving the respect and support that the dignity of his high office deserved. So, in a showdown with the Church, he refused to invest the Pope's candidate as Archbishop of Canterbury. Innocent III's reply was to place England under interdict, which meant that for years no baptisms, marriages, Christian burials - or any other sacrament - could take place in the realm.

Moreover, since much of the baronage had shown itself less than eager to support the king, John stopped consulting it as feudal custom required. He withdrew further and further from view, and if he sought advice at all, it was only from his inner circle of advisors, those few whose unwavering loyalty to him had been thoroughly tested in the six crises of his life that far.

Hostilities continued, for the king was not about to do the easy thing, the popular thing, and end the war. That would have reduced him to a pitiful, helpless giant, and England to a second-rate power. So, regardless of what his subjects might think, John continued to prosecute the war and meet his obligations. To seize control of the situation, he decided to take full advantage of the power inherent in the increasingly centralized government that had grown up over the previous forty years. His own men were installed in the great governmental departments. Increasingly, every possible means was used to squeeze money out of people, for if they would not fight the war themselves, he would use their money to create a volunteer army, mercenaries with whom it could be continued. Money was debased to stretch its use, though at the price of inflation; favors were sold to friends of the regime at a high price; and every legal right of the government was bent and stretched to its own advantage to gain added revenue.

Reliefs (inheritance duties) for succeeding to fiefs were raised ten-fold and more; the hands of widows and heiresses were auctioned off to the highest bidders; huge fees were exacted for obtaining writs of justice; fiefs in the wardship of the state during the minority of their holders were stripped of all saleable property - forests, cattle, equipment; aids (the medieval equivalent of taxes) were levied without consent or traditional justification. As Magna Carta was later to testify, the list is well-nigh endless.

Among the people there was a growing and articulate opposition. But the government was tough. When, for example, student protest broke out at Oxford in 1209, royal troops were dispatched to suppress it. These crossbowmen simply shot down both students and masters, and that broke the back of the movement. Many scholars and their disciples decided to drop out, leaving Oxford to wander in search of some more quiet and remote spot where they could establish their own free university. And they were successful, for these downtrodden outcasts were to be the founders of Cambridge.

But that event was no more than a happy footnote in a far grimmer picture. with students repressed, the government turned its attention to the rest of its subjects. The Justiciar - the chief law-enforcement officer of the realm - began placing suspected enemies in preventive detention; people were imprisoned, multilated, or executed without indictment or trial; royal spies and informers were hired to ferret out all evidence of disloyalty and subversion.

How much of this King John knew in detail is highly uncertain. After all, he was seldom in the capital, preferring to spend his time visiting foreign dignitaries and travelling from one royal palace to another all over England. at did make it hard for information to reach him, although (as more suspicious historians point out) that had its advantages. As did, heaven knows, the fact that the most important royal court travelled with him. If a Plaintiff could never catch up with the judges, which often happened, no difficult cases could be brought for decision, thus preserving the tranquillity of the royal progresses.

Nevertheless, there came a time, in 1213, when John finally began to realize the difficulties of his position. Despite his best efforts, Normandy had fallen to the French; the interdict continued; and the intensity of complaint in the kingdom reached a level that could no longer be evaded. John responded with seeming political brilliance. First, he came to terms with the Church accepting its candidate, Stephen Langton, as Archbishop of Canterbury In return, the interdict was lifted. Then, to show his good faith, he announced he was taking the Cross and becoming a Crusader.

In a sense, John was wrapping himself in the flag since crusading was in medieval terms, very close to patriotism. Again, however, cynics have justifiable grounds for suspicion, for if crusading was the noblest calling in Christendom, it is also true that being a Crusader had certain practical advantages. First, those taking the Cross were relieved, for a period of three years, of all obligation to pay their debts. No legal cases could be heard against them for a similar period. Their persons were endowed with a peculiarly sacrosanct character that safeguarded them from physical attack by any Christian having a concern for the future of his own immortal soul. Last, but not least, Crusaders had the unassailable right to collect a special crusading aid from all of their vassals, the better to support them on their holy mission.

Maybe John was serious, but with him one never knows. What can be determined is that once he had taken the Cross and collected his aid, he used the money to hire mercenaries and attract allies. In 1214, he again invaded France. The first result of his actions was the battle of Bouvines, about the most complete military disaster the English have ever experienced in a long history that seems to glory in such disasters.

The second result was Magna Carta. Provoked beyond endurance, the barons of England rose, led (as it happened) by Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury. John ducked, parried, and fled, but in the end he was cornered, as the charter concludes, "in the meadow which is called Runnymede between Windsor and Staines on the fifteenth day of June in the seventeenth year of our reign." He was to die the following year, 1216, in the midst of new revolts that his still unyielding stubbornness had provoked. Though only 49 at his death, he had lived a full life and was richly deserving of the sobriquets "Lackland" and "Softsword" that his contemporaries had so scornfully bestowed on him.

Historians - royalists all - have tended to see Magna Carta as a reactionary document, and in many ways they are right. Chapter after chapter promises a return to "ancient liberties" and "customary services," concessions which, when examined, turn out to be as selfish as they are unrealistic. Similarly, in its origins Magna Carta is much more a political than constitutional document, little more than a treaty of peace wrested from an unwilling king by those who had risen in armed and unlawful rebellion against him.

Yet that is hardly the full story. Lurking behind each of those reactionary chapters is a fine medieval principle, one we would do well to recall: Lexregem facit, non rex legem - "The law makes the king, not the king the law." And some, today, would surely find a certain appeal in the provisions of Chapter 45:

We will not make justices, constables, sheriffs or bailiffs who do not know the law of the land and mean to observe it well.

If so, then Chapters 39 and 40 will prove equally appealing:

No free man shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.

Reactionary views have seldom received a fair hearing; perhaps it is time that they did.

By 1200 the military was becoming quiteprofessionalized and its weaponry evermore expensive. This mounted knight, instained glass, is from an Essex church.

A medieval archer cocking his crossbow.John's troops also were employed to maintain law and order within the kingdom.

John's contemporaries, like artist-chronicler Matthew Paris, watched whathe did, not what he said. Paris recordedthese scenes of royal oppression in 1216.

John's contemporaries, like artist-chronicler Matthew Paris, watched whathe did, not what he said. Paris recordedthese scenes of royal oppression in 1216.

John's vassals were none too loyal andtheir kiss of peace resembled Judas'. A13th-century tile from Chertsey, England.

He who does not know the past is condemned to repeat it - George Santayana.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

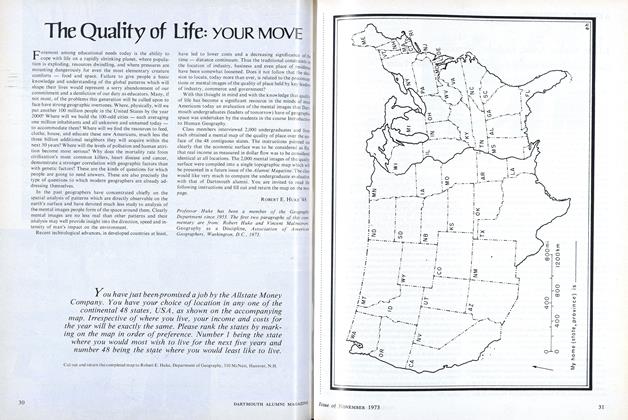

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

November 1973 By ROBERT E. HUKE'48 -

Feature

FeatureA PORTFOLIO OF THE Dartmouth Cemetery

November 1973 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleEditor, Banker, Artist, Engineer, Physicist Dartmouth's Post-War Refugee Students 25 Years Later

November 1973 By HARRIET GUNDERSEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTG.OMERY, C. HALL COLTON -

Article

ArticleTHE FBI AND ME or, How I Didn't Shoot Eisenhower

November 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING'25

CHARLES T. WOOD

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JUNE 1971 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JUNE 1978 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1978 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY • 1988 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorThe Games Were Glorious

MARCH 2000 -

Feature

FeatureA Humanist Ponders the Future of Liberal Education

June • 1985 By Charles T. Wood

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryTechnology Now and in the Future

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMariam Malik '98

OCTOBER 1997 By Deborah Solomon -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO MOLD YOUR CHILD INTO IVY MATERIAL

Jan/Feb 2009 By HOWARD GREENE '59 AND SON MATTHEW GREENE '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO NAIL A PERFECT FIELD GOAL

Jan/Feb 2009 By NICK LOWERY '78 -

Cover Story

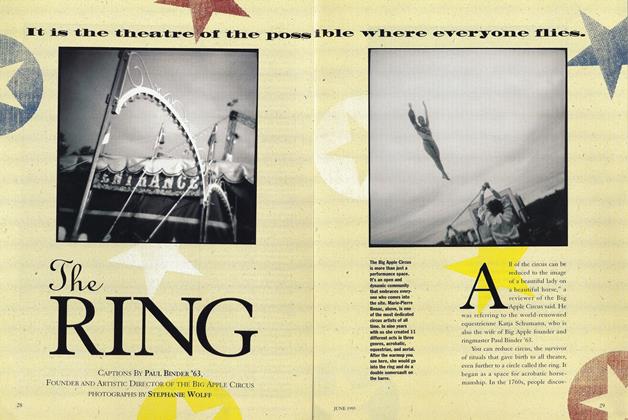

Cover StoryThe RING

June 1995 By Paul Binder '63 -

Feature

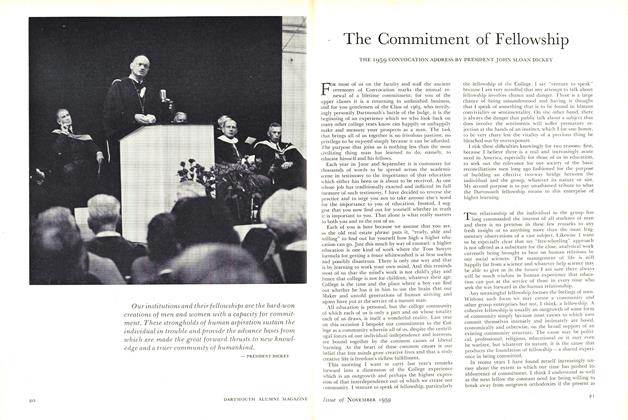

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY