A handyman's memoir of Jose Clemente Orozco

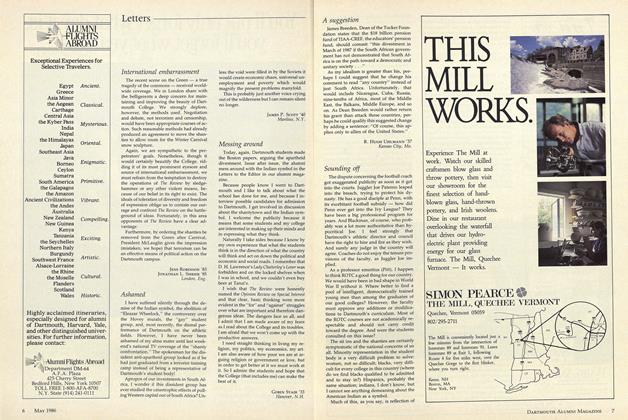

Forty years ago now, in the winter, spring, summer, fall, and winter again, the Dartmouth mural was being painted by Jose Clemente Orozco, and I watched it happen day after day. It is still, just as it was then, a surprise to me each time I see it—fresh and prophetic and colorful, a full, repetitive but varied experience.

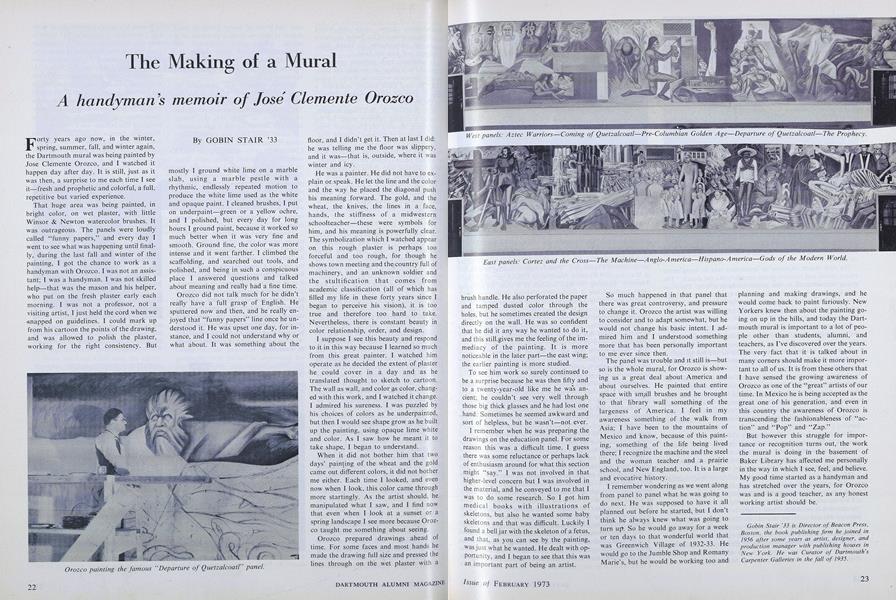

That huge area was being painted, in bright color, on wet plaster, with little Winsor & Newton watercolor brushes. It was outrageous. The panels were loudly called "funny papers," and every day I went to see what was happening until finally, during the last fall and winter of the painting, I got the chance to work as a handyman with Orozco. I was not an assistant; I was a handyman. I was not skilled help—that was the mason and his helper, who put on the fresh plaster early each morning. I was not a professor, not a visiting artist, I just held the cord when we •snapped on guidelines. I could mark up from his cartoon the points of the drawing, and was allowed to polish the plaster, working for the right consistency. But mostly I ground white lime on a marble slab, using a marble pestle with a rhythmic, endlessly repeated motion to produce the white lime used as the white and opaque paint. I cleaned brushes, I put on underpaint—green or a yellow ochre, and I polished, but every day for long hours I ground paint, because it worked so much better when it was very fine and smooth. Ground fine, the color was more intense and it went farther. I climbed the scaffolding, and searched out tools, and polished, and being in such a conspicuous place I answered questions and talked about meaning and really had a fine time.

Orozco did not talk much for he didn't really have a full grasp of English. He sputtered now and then, and he really enjoyed that "funny papers" line.once he understood it. He was upset one day, for instance, and I could not understand why or what about. It was something about the floor, and I didn't get it. Then at last I did: he was telling me the floor was slippery, and it was—that is, outside, where it was winter and icy.

He was a painter. He did not have to explain or speak. He let the line and the color and the way he placed the diagonal push his meaning forward. The gold, and the wheat, the knives, the lines in a face, hands, the stiffness of a midwestern schoolteacher—these were symbols for him, and his meaning is powerfully clear. The symbolization which I watched appear on this rough plaster is perhaps too forceful and too rough, for though he shows town meeting and the country full of machinery, and an unknown soldier and the stultification that comes from academic classification (all of which has filled my life in these forty years since I began to perceive his vision), it is too true and therefore too hard to take. Nevertheless, there is constant beauty in color relationship, order, and design.

I suppose I see this beauty and respond to it in this way because I learned so much from this great painter. I watched him operate as he decided the extent of plaster he could cover in a day and as he translated thought to sketch to cartoon. The wall as wall, and color as color, changed with this work, and I watched it change. I admired his sureness. I was puzzled by his choices of colors as he underpainted, but then I would see shape grow as he built up the painting, using opaque lime white and color. As I saw how he meant it to take shape, I began to understand.

When it did not bother him that two days' painting of the wheat and the gold came out different colors, it did not bother me either. Each time I looked, and even now when I look, this color came through more startingly. As the artist should, he manipulated what I saw, and I find now that even when I look at a sunset or a spring landscape I see more because Orozco taught me something about seeing.

Orozco prepared drawings ahead of time. For some faces and most hands he made the drawing full size and pressed the lines through on the wet plaster with a brush handle. He also perforated the paper and tamped dusted color through the holes, but he sometimes created the design directly on the wall. He was so confident that he did it any way he wanted to do it, and this still-gives me the feeling of the immediacy of the painting. It is more noticeable in the later part—the east wing; the earlier painting is more studied.

To see him work so surely continued to be a surprise because he was then fifty and to a twenty-year-old like me he was ancient; he couldn't see very well through those big thick glasses and he had lost one hand/ Sometimes he seemed awkward and sort of helpless, but he wasn't—not ever.

I remember when he was preparing the drawings on the education panel. For some reason this was a difficult time. I guess there was some reluctance or perhaps lack of enthusiasm around for what this section might "say." I was not involved in that higher-level concern but I was involved in the material, and he conveyed to me that I was to do some research. So I got him medical books with illustrations of skeletons, but also he wanted some baby skeletons and that was difficult. Luckily I found a bell jar with the skeleton of a fetus, and that, as you can see by the painting, was just what he wanted. He dealt with opportunity, and I began to see that this was an important part of being an artist.

So much happened in that panel that there was great controversy, and pressure to change it. Orozco the artist was willing to consider and to adapt somewhat, but he would not change his basic intent. I admired him and I understood something more that has been personally important to me ever since then.

The panel was trouble and it still is—but so is the whole mural, for Orozco is showing us a great deal about America and about ourselves. He painted that entire space with small brushes and he brought to that library wall something of the largeness of America. I feel in my awareness something of the walk from Asia; I have been to the mountains of Mexico and know, because of this painting, something of the life being lived there; I recognize the machine and the steel and the woman teacher and a prairie school, and New England, too. It is a large and evocative history.

I remember wondering as we went along from panel to panel what he was going to do next. He was supposed to have it all planned out before he started, but I don't think he always knew what was going to turn up; So he would go away for a week or ten days to that wonderful world that was Greenwich Village of 1932-33. He would go to the Jumble Shop and Romany Marie's, but he would be working too and planning and making drawings, and he would come back to paint furiously. New Yorkers knew then about the painting going on up in the hills, and today the Dartmouth mural is important to a lot of people other than students, alumni, and The very fact that it is talked about in many corners should make it more important to all of us. It is from these others that I have sensed the growing awareness of Orozco as one of the "great" artists of our time. In Mexico he is being accepted as the great one of his generation, and even in this country the awareness of Orozco is transcending the fashionableness of "action" and "Pop" and "Zap."

But however this struggle for importance or recognition turns out, the work the mural is doing in the basement of Baker Library has affected me personally in the way in which I see, feel, and believe. My good time started as a handyman and has stretched over the years, for Orozco was and is a good teacher, as any honest working artist should be.

Orozco painting the famous "Departure of Quetzalcoatl" panel.

West panels: Aztec Warriors—Coming of Quetzalcoatl—Pre-Columbian Golden Age—Departure of Quetzalcoatl—The Prophecy.

East panels: Cortez and the Cross—The Machine—Anglo-America—Hispano-America—Gods of the Modem World.

Gobin Stair '33 is Director of Beacon Press,Boston, the book publishing firm he joined in1956 after some years as artist, designer, andproduction manager with publishing houses inNew York. He was Curator of Dartmouth'sCarpenter Galleries in the fall of 1935.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1973 -

Feature

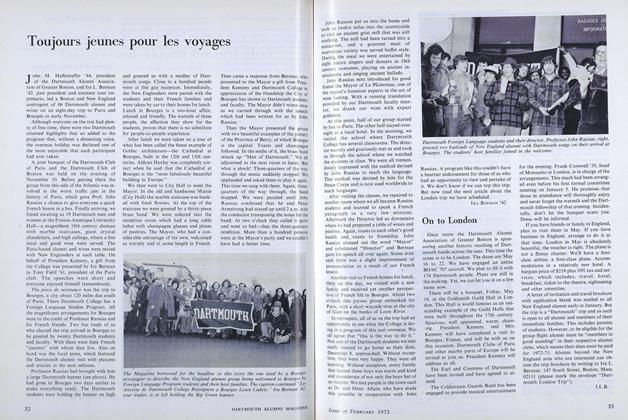

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

February 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Feature

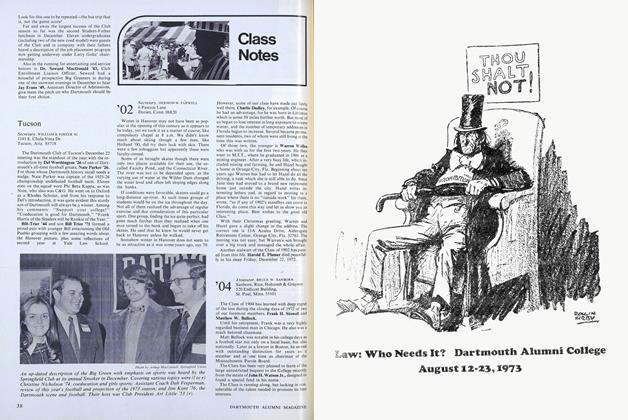

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

February 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

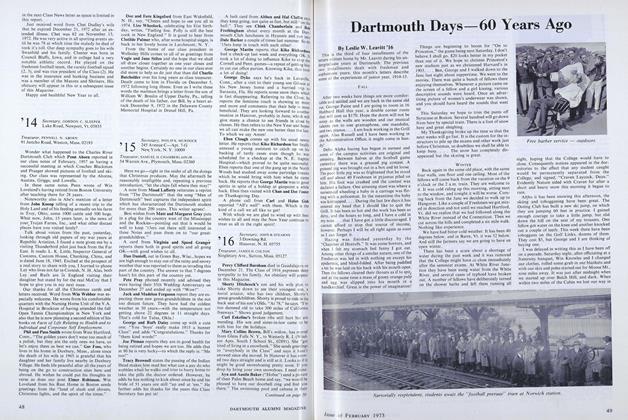

ArticleDartmouth Days—60 Years Ago

February 1973 By Leslie W. Leavitt '16

GOBIN STAIR '33

Features

-

Feature

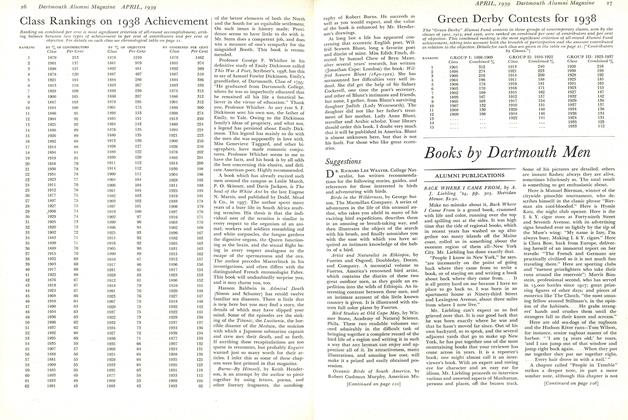

FeatureGlass Rankings on 1938 Achievement

April 1939 -

Feature

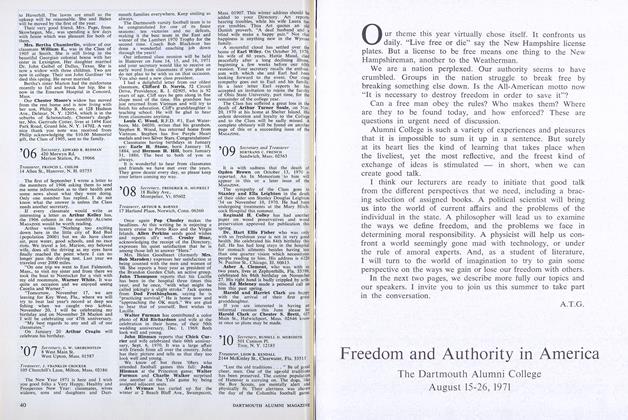

FeatureThe Dartmouth Alumni College August 15-26, 1971

JANUARY 1971 By A.T.G. -

Feature

FeatureThe Outsider

May/June 2013 By BRUCE ANDERSON -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureBattle Scarred

Sep - Oct By JAMES WRIGHT -

Feature

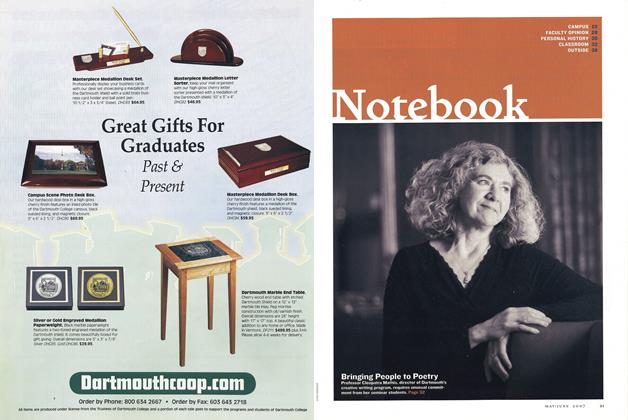

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN