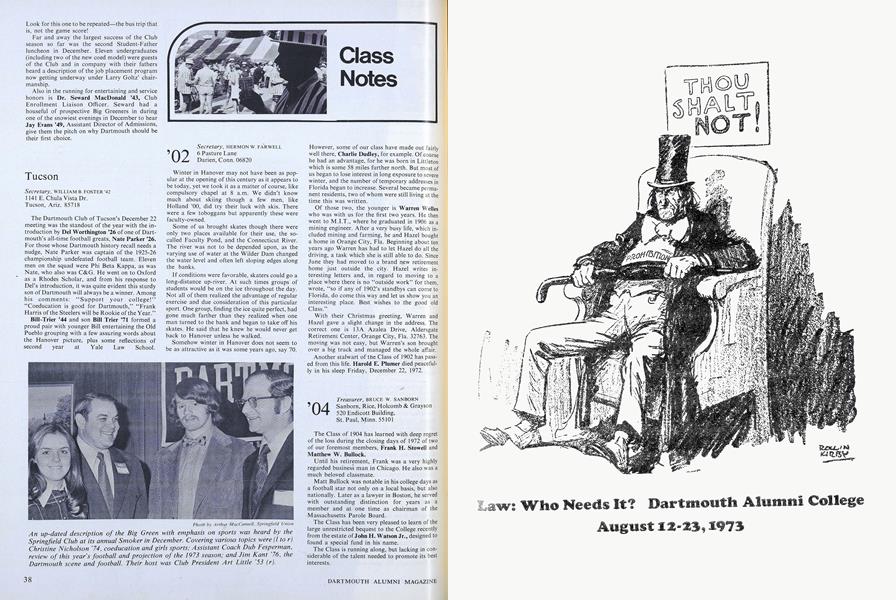

Law; Who Needs It?

August 12-23,1973

Law: Who Needs It?

Law, says the judge as he looks down his nose, Speaking clearly and most severely, Law is as I've told you before, Law is as you know I suppose, Law is but let me explain it once more, Law is The Law.

Thus W. H. Auden's "Law Like Love," a poem wrestling with issues old as man, yet fresh as this morning's newspaper. Every day we read of Law under seige, but all too often like Auden's judge we seem incapable of understanding just what is being attacked—or whether it is worth defending.

Joining Auden. this year's Alumni College will explore the meaning and purpose of Law. Is it like Roland Kirby's version of Prohibition, nothing more than a blue-nosed Puritan muttering "Thou shalt not!" from between clenched teeth? If so, its attackers may gain our sympathy. On the other hand, the very history of Prohibition itself suggests the issues aren't that easy. For over twelve years abstinence was the constitutional law of the land, but that did little to halt the sale of alcohol or its consumption. At the same time, flagrant disregard of this particular law did little to undermine the constitution or other aspects of the legal process. Are we to conclude, then, that legislation becomes Law only when enforced and enforceable? That is scarcely a happy thought for those like Auden's judge who hold that "Law is The Law."

Most of us (non-lawyers, at least) find Law a bit frightening, an arcane field whose very language lies beyond the grasp of those not trained in its intricacies. Yet such fears are largely groundless, for, obscure though specific legislation may often be, the principles of jurisprudence rest on propositions and assumptions familiar to us all. Take, for example, Chapter 39 of Magna Carta:

No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him nor send upon him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

While some specifics may elude us—what it means to be "disseised" or what the term "freeman" meant in 1215—nevertheless we can easily grasp both the barons' intent and the general principles underlying their case.

Nor should this really surprise us because the truth of the matter is that a search for Law and Justice lies at the heart of much of our culture. To read much of Shakespeare or, less grandiloquently, even a modern detective story, is immediately to be captured by questions of Justice, Equity, and Law. Similarly, to follow Henry Kissinger's endless peregrinations is to transfer the same interests to the international scene and to ponder whether affairs of state can ever be brought under rules that are universally recognized and universally observed. Even the social scientist is increasingly forced to ask whether work in that field can be properly conducted without reference to those moral concerns to which Law and social order are commonly assumed to give expression.

This, then, is the subject matter of Alumni College, a wide-ranging examination of the role of Law, its functioning, purpose, and prin- ciples. I cannot predict where we shall come out on all of this, but it seems safe to say that, wherever we conclude, the getting there is going to be searching, possibly contentious, and certainly lively.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1973 -

Feature

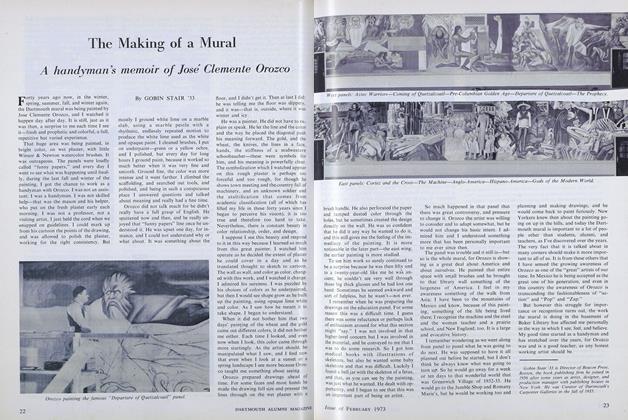

FeatureThe Making of a Mural

February 1973 By GOBIN STAIR '33 -

Feature

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

February 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Days—60 Years Ago

February 1973 By Leslie W. Leavitt '16

Features

-

Feature

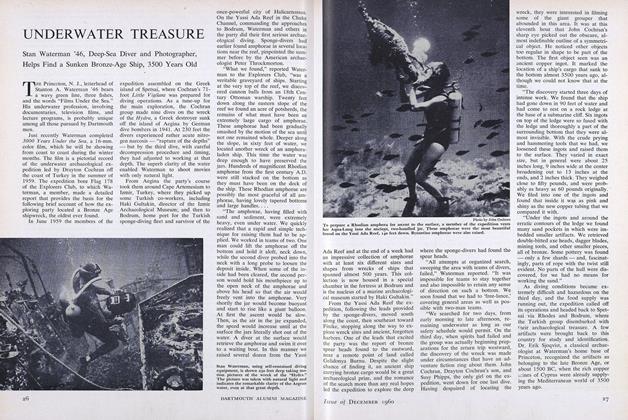

FeatureUNDERWATER TREASURE

December 1960 -

Feature

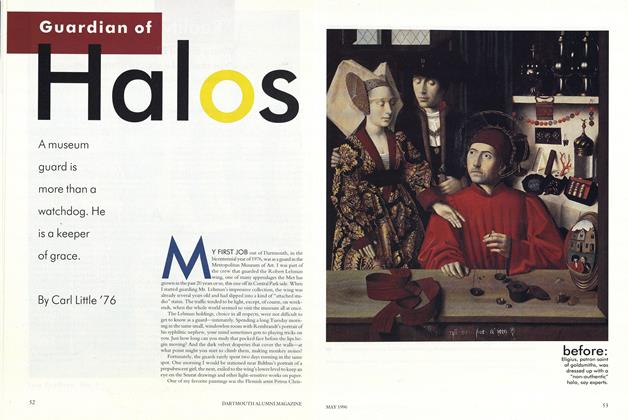

FeatureGuardian of Halos

MAY 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

JUNE 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureMAIN STREET

JUNE 1982 By Nancy Wasserman -

Feature

FeatureThe Underground Curriculum

October 1992 By Tim Brookes