Eric Easterly's paper, submitted for Prof. Roger Masters'government course, treats the nature of man as seen differentlyby Hobbes and Rousseau.

"But the most noble and profitable invention of all others was that of speech, consisting of names or appellations, and their connexion; whereby men register their thoughts; recall them when they are past; and also declare them to one another for mutual utility and conversation; without which there had been amongst men, neither commonwealth, nor society, nor contract, nor peace, no more than amongst lions, bears and wolves."

From the implications in this statement by Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan I can make one interesting deduction: that there existed a state of nature prior to the Hobbesian state of nature, which is to be distinguished from the latter by the absence of mong men.

speech among men.

I will consider first why speech is so important to Hobbes; second, sketch some of the characteristics of this "speechless" state of nature; and, finally, make some rough comparisons between it and Rousseau's state of nature.

The importance of speech for Hobbes can easily be seen in his definition of reason: "For reason in this sense, is nothing but reckoning, that is adding and subtracting of the consequences of general names agreed upon for the marking and signifying of our thoughts." Plainly for Hobbes speech is a necessary prerequisite for reason. Elsewhere he writes, "Children therefore are not endued with reason at all till they have attained the use of speech."

Hobbes has essentially narrowed the accepted definition of reason, defining it to be a specific use of speech and insisting that it "is not, as sense and memory, born with use; nor gotten by experience only as prudence is; but attained by industry ..."

For Hobbes reason arises from the union of speech and a particular, inherent faculty found only in man which he describes as follows: "... that when he conceived anything whatsoever he was apt to inquire the consequences of it and what effects he could do with it." While other thinkers might wish to include this faculty in their definition of reason, Hobbes prefers to call it seeking" or "the faculty of invention."

More importantly, reason is the fulcrum on which rest Hobbes' political constructions. Without reason a man cannot know the laws of nature. "A law of nature ... is a precept or general rule found out by reason, by which a man is forbidden to do that which is destructive of his life, or taketh away the means of preserving the same." Certainly a man, with or without reason (as Hobbes defines it), has the inalienable right at all times to pursue whatever course of action he deems necessary to his self Preservation, but he cannot, without aid of reason, determine what, in fact, is most conducive to his existence ... that is, he cannot know that to "seek peace and follow it" is best suited to the preservation of his nature; and even if he could know this instinct, he would not know the means by which to accomplish it. He would know neither justice nor convenant; and hence there could be "neither commonwealth, nor society, nor contract, nor peace ..."

Speech gave men the potential for political action. Withoutspeech, men could not declare their purposes and intentions to one another and.hence could not unite in common purpose.

Neither property nor family relationships could exist. "For in the condition of mere nature, where there are no matrimonial laws, it cannot be known who is the father, unless it be declared by the mother."

Furthermore, since men cannot effectively unite, the power of a particular man to dominate another is determined by the difference in their respective faculties of the body and mind; but Hobbes has this to say: "Nature hath made men so equal in the faculties of the body, and the mind; as that though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body, or of quicker mind than another; yet when, all be reckoned together the difference between man and man is not so considerable as that one man can there upon claim to himself any benefit to which another may not pretend as well as he."

According to Hobbes, the relationship that a man in this state would have with his fellow men is one of war . . . but examine his definition of war: "... a tract of time, wherein the will to contend by battle is sufficiently known," which does not necessarily imply continual fighting.

Summing the foregoing considerations provides a rough model of the condition of man prior to the invention of speech, according to Hobbes' arguments. Imagine then a man, unable to communicate with his fellow men, leading a solitary existence, forever prepared to do battle with man or animal when he judges it within his interest to do so. He would have only so much peace as exists "amongst lions, bears, and wolves." He would not know "mine" from "thine." He could neither dominate men nor be dominated by them. He would have no family. Such attributes of speech as truth or falsehood he would not know, nor would he perceive justice or injustice.

Compare this man now to Rousseau's "savage man." In the Second Discourse he describes him as "alone, idle, and always near danger ..." "His self preservation being almost his only care, his best-trained faculties must be those of having as principal object attack and defense ..." There would exist no moral relationship between him and his fellow men. "... they had no kind of commerce among themselves ... consequently, they knew neither vanity nor consideration, nor esteem nor contempt . . . they did not have the slightest notion of mine and thine, nor any true ideas of justice." Finally, concerning families, Rousseau writes "... there was one appetite that invited him to perpetuate his species; and this blind inclination, devoid of any sentiment of the heart, produced only a purely animal act. This need satisfied, the two sexes no longer recognized each other and even the child no longer meant anything to his mother as soon as he could do without her."

The comparisons are by no means exahusted but suffice it to say that Hobbes' notion of the condition of men lacking the faculty of speech seems remarkably similar to Rousseau's concept of the state of nature.

There are differences, of course. Rousseau attributes to men an inherent sense of natural pity "in support of reason" from which he ultimately derives the social virtues, whereas Hobbes was content to base morality solely on reason. Rousseau derives men's passions from their needs alone; for Hobbes, these passions arise both from their needs and their desires.

There are other differences, less important, but I believe that the ultimate source of difference between the teachings of Hobbes and those of Rousseau is found in their respective attitudes toward life. The man whom Hobbes called "miserable" Rousseau called "free." Hobbes saw animals at war with one another; Rousseau found them at peace. For Hobbes savage man was "brutish" but for Rousseau, he was simply ''good."

Rousseau suggests that other thinkers have searched for the state of nature but failed because they did not go back far enough in man's history. I think that very likely Hobbes did consider man's earliest state of nature but discarded it as unnecessary. Hobbes had only to go back to the state of war "wherein every man is enemy to every man" to discover man's nature and thus the ultimate source of civil society. Rousseau, on the other hand, found only a corruption of man's nature in the state of war and so was forced to journey further to discover man's true nature. Savage man became, for Rousseau, a standard of excellence, but Hobbes saw nothing of the excellence, only the savageness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

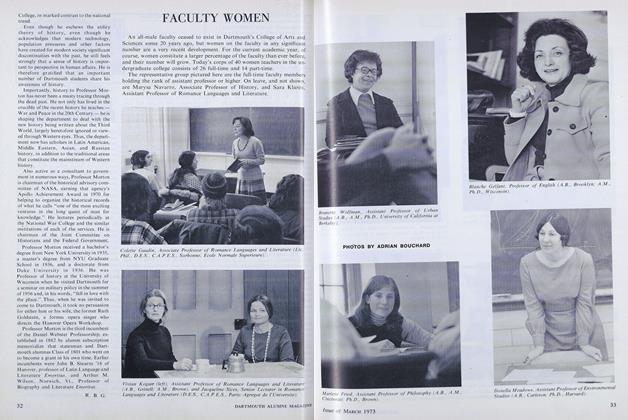

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73

Article

-

Article

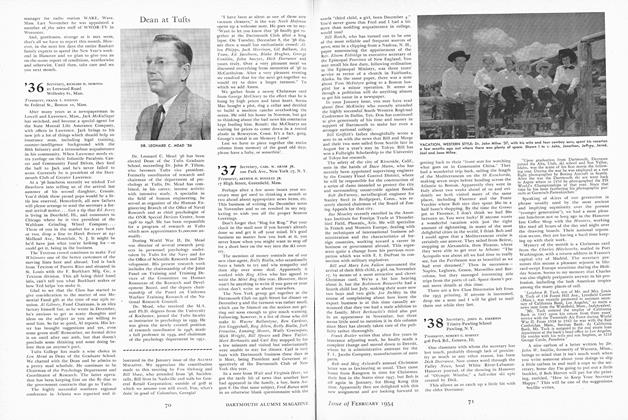

ArticleDean at Tufts

February 1954 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

December 1994 -

Article

ArticleNazis In the Hood?

Mar/Apr 2002 -

Article

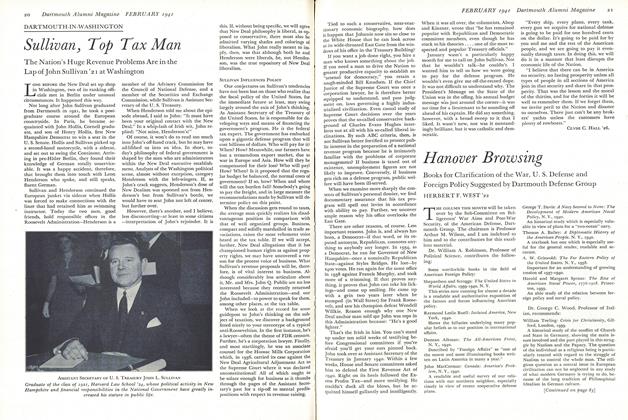

ArticleSullivan, Top Tax Man

February 1941 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleSo Much More Than a Reunion

June 1994 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Club

March 1940 By Hans Paschen '28T