By William C. Scott (AssociateProfessor and Chairman, Department ofClassics). Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J.Brill, 1974. 212 pp. $18.

What are similes? They are a means of description and of highlighting: where Homer (or Solon or Vergil or Dante or Milton or any poet who composes in the epic manner) breaks off his narrative of events to describe the advance of a hero or an army, the feelings of a counselor or a leader or the tears of a heroine (or hero) by telling us what they are like. These comparisons may be very brief, or they may be extended at length until the likeness seems to be carried on more for its own sake than because of any immediate relevance or point of contact with the narrative. It is this fact, perhaps, which has suggested to many that, whereas the narrative is largely traditional, that is, formulaic, oral in substance and manner, the similes are the poet's own original contribution to the whole epic.

Professor Scott would dispute this view. The similes are, like the rest, a part, admittedly variable, of the whole tradition and composed in the same manner as the rest of the Homeric epic, that is, by the use of formulaic metrical phrases. Here I could wish that Professor Scott had drawn a sharper distinction between the minute, two-word, two-foot simile, and the extended comparison of two or far more than two lines. The former simply are formulaic phrases. If you say that a man is "like a god" (daimoniisos) or that he is "a godlike man" (isotheosphos), the former is here called a simile, the latter is not; yet both say exactly the same thing and close the line in exactly the same way, and both are the same kind of formulaic phrase, frequently repeated.

It is when the extended similes are analysed that the point is really made; that most similes fall into place according to particular demands from the narrative scene, and in particular groups. Lions and boars, for instance, are for heroes, and deer are for terrified people; anything unwarlike is for losers, or rather, losers' similes are unwarlike. This kind of grouping, it is freely admitted, does not always work. Penelope, for instance, is once represented by a lion. But on the whole, the analysis is far-reaching and convincing. In sum, the whole use of similes is developed out of the same elements as the rest of the epics.

The crucial statement of this is to be found on page 140: "It is possible to demonstrate ... that the majority of longer similes were composed by extending the basic simile unit through the addition of separate lines and half-lines which are not organically related to each other or to the simile as a whole, the extended simile being as much a product of oral composition as the narrative." The chief aim of the poet, that is, story-telling not shock or surprise, total effect not originality, has seldom been more consistently expounded. The abundant quotations from the text are regularly translated into accurate. and readable prose and, though the book is clearly meant for scholars, the Greekless may find it interesting and enlightening.

The Bryn Mawr retired professor, internationally known as "the dean of American classicaltranslators." Mr. Lattimore has received theBollingen Translation Prize, served as Fulbrightlecturer abroad, and been elected to theNational Institute of Arts and Letters.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"THE KINGDOM OF GOD HAS COME"

October 1974 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

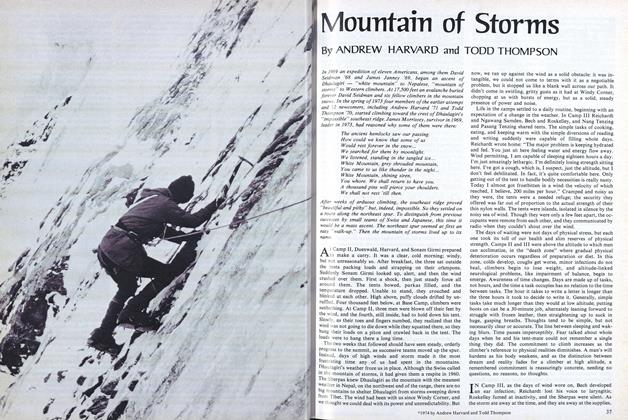

FeatureMountain of Storms

October 1974 By ANDREW HARVARD, TODD THOMPSON -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1974 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE MINER

Books

-

Books

BooksSEVENTY DARTMOUTH POEMS.

MARCH 1971 By A. INSKIP DICKERSON JR. '56 -

Books

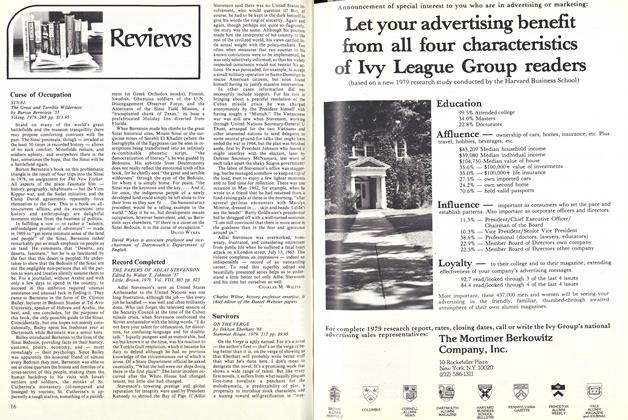

BooksCurse of Occupation

March 1980 By David Wykes -

Books

BooksTHE HAND IN THE PICTURE,

November 1947 By Eric P., THEODORE KARWOSKI -

Books

BooksOUTPOSTS OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOL

April 1939 By Highly Recommended, Louis P. Benezet '99 -

Books

BooksARCHITECTURE OF THE WESTERN RESERVE, 1800-1900.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE GOLDEN STAR OF HALICH; A TALE OF THE RED LAND IN

NOVEMBER 1931 By W. R. Waterman