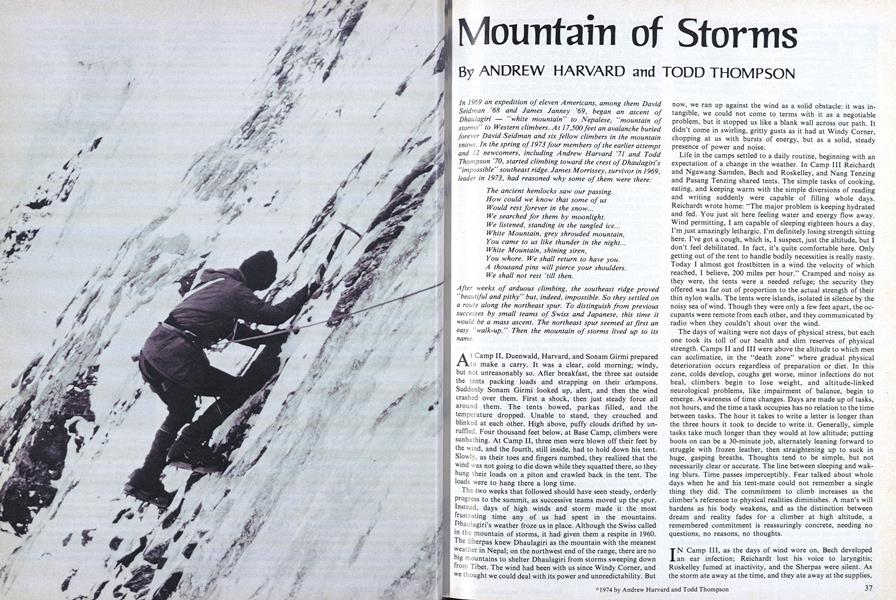

In 1969 an expedition of eleven Americans, among them DavidSeidman '68 and James Janney '69, began an ascent ofDhaulagiri "white mountain" to Nepalese, "mountain ofstorms" to Western climbers. At 17,500 feet an avalanche buriedforever David Seidman and six fellow climbers in the mountainsnows. In the spring of 1973 four members of the earlier attemptand 12 newcomers, including Andrew Harvard '71 and ToddThompson '70, started climbing toward the crest of Dhaulagiri's"impossible" southeast ridge. James Morrissey, survivor in 1969,leader in 1973, had reasoned why some of them were there:The ancient hemlocks saw our passing.How could we know that some of usWould rest forever in the snow...We searched for them by moonlight.We listened, standing in the tangled ice...White Mountain, grey shrouded mountain,You came to us like thunder in the night...White Mountain, shining siren,You whore. We shall return to have you.A thousand pins will pierce your shoulders.We shall not rest 'till then.After weeks of arduous climbing, the southeast ridge proved"beautiful and pithy" but, indeed, impossible. So they settled ona route along the northeast spur. To distinguish from previoussuccesses by small teams of Swiss and Japanese, this time itwould be a mass ascent. The northeast spur seemed at first aneasy "walk-up." Then the mountain of storms lived up to itsname.

At Camp II, Duenwald, Harvard, and Sonam Girmi prepared to make a carry. It was a clear, cold morning; windy, but not unreasonably so. After breakfast, the three sat outside the tents packing loads and strapping on their cràmpons. Suddenly Sonam Girmi looked up, alert, and then the wind crashed over them. First a shock, then just steady force all around them. The tents bowed, parkas filled, and the temperature dropped. Unable to stand, they crouched and blinked at each other. High above, puffy clouds drifted by unruffled. Four thousand feet below, at Base Camp, climbers were sunbathing. At Camp II, three men were blown off their feet by the wind, and the fourth, still inside, had to hold down his tent. Slowly, as their toes and fingers numbed, they realized that the wind was not going to die down while they squatted there, so they hung their loads on a piton and crawled back in the tent. The loads were to hang there a long time.

The two weeks that followed should have seen steady, orderly progress to the summit, as successive teams moved up the spur. Instead, days of high winds and storm made it the most frustrating time any of us had spent in the mountains. Dhaulagiri's weather froze us in place. Although the Swiss called in the mountain of storms, it had given them a respite in 1960. The Sherpas knew Dhaulagiri as the mountain with the meanest weather in Nepal; on the northwest end of the range, there are no big mountains to shelter Dhaulagiri from storms sweeping down from Tibet. The wind had been with us since Windy Corner, and we thought we could deal with its power and unpredictability. But now, we ran up against the wind as a solid obstacle: it was intangible, we could not come to terms with it as a negotiable problem, but it stopped us like a blank wall across our path. It didn't come in swirling, gritty gusts as it had at Windy Corner, chopping at us with bursts of energy, but as a solid, steady presence of power and noise.

Life in the camps settled to a daily routine, beginning with an expectation of a change in the weather. In Camp III Reichardt and Ngawang Samden, Bech and Roskelley, and Nang Tenzing and Pasang Tenzing shared tents. The simple tasks of cooking, eating, and keeping warm with the simple diversions of reading and writing suddenly were capable of filling whole days. Reichardt wrote home: "The major problem is keeping hydrated and fed. You just sit here feeling water and energy flow away. Wind permitting, I am capable of sleeping eighteen hours a day. I'm just amazingly lethargic. I'm definitely losing strength sitting here. I've got a cough, which is, I suspect, just the altitude, but I don't feel debilitated. In fact, it's quite comfortable here. Only getting out of the tent to handle bodily necessities is really nasty. Today I almost got frostbitten in a wind the velocity of which reached, I believe, 200 miles per hour." Cramped and noisy as they were, the tents were a needed refuge; the security they offered was far out of proportion to the actual strength of their thin nylon walls. The tents were islands, isolated in silence by the noisy sea of wind. Though they were only a few feet apart, the occupants ere remote from each other, and they communicated by radio when they couldn't shout over the wind.

The days of waiting were not days of physical stress, but each one took its toll of our health and slim reserves of physical strength. Camps II and III were above the altitude to which men can acclimatize, in the "death zone" where gradual physical deterioration occurs regardless of preparation or diet. In this zone, colds develop, coughs get worse, minor infections do not heal, climbers begin to lose weight, and altitude-linked neurological problems, like impairment of balance, begin to emerge. Awareness of time changes. Days are made up of tasks, not hours, and the time a task occupies has no relation to the time between tasks. The hour it takes to write a letter is longer than the three hours it took to decide to write it. Generally, simple tasks take much longer than they would at low altitude; putting boots on can be a 30-minute job, alternately leaning forward to struggle with frozen leather, then straightening up to suck in huge, gasping breaths. Thoughts tend to be simple, but not necessarily clear or accurate. The line between sleeping and waking blurs. Time passes imperceptibly. Fear talked about whole days when he and his tent-mate could not remember a single thing they did. The commitment to climb increases as the climber's reference to physical realities diminishes. A man's will hardens as his body weakens, and as the distinction between dream and reality fades for a climber at high altitude, a remembered commitment is reassuringly concrete, needing no questions, no reasons, no thoughts.

IN Camp III, as the days of wind wore on, Bech developed an ear infection; Reichardt lost his voice to laryngitis; Roskelley fumed at inactivity, and the Sherpas were silent. As the storm ate away at the time, and they ate away at the supplies, the expedition's chance of multiple ascents dwindled. Instead of being the first wave, they were becoming the last resort.

Camp II was not a comfortable place to wait. The tents at Camp II were completely exposed to the wind, and very precariously pitched, conditions which brought the weather indoors. Duenwald and Harvard occupied one tent, Thompson a second, and Sonam Girmi the third. There were stoves in Thompson's and Sonam Girmi's tents; when the weather allowed they ate crowded together in Thompson's tent. The schedule gradually changed from three short meals to one long one a day, to eliminate dangerous trips between tents. Duenwald and Harvard could crawl from the entrance of their tent and half-climb, half-slide down ten feet of rope to crash through the front door of Thompson's tent. Sonam Girmi had to put on crampons to jumar up the twenty feet from his tent. Meals in Camp II were important social events, though the sociability was briefly threatened when Harvard, whose digestive system had been disrupted by codeine cough syrup, developed an inability to hold his food down. He would eat voraciously, smile contentedly, and then throw the whole thing up into a plastic bag. Whoever was nearest the door would throw the bag out, signaling the end of the meal. It didn't bother Harvard nearly as much as it did those who had to watch, but he wasn't getting enough to eat.

In a safe, warm hole, a wind howling outside can be a soothing thing, but in a small, insecure tent, it banishes all hope of comfort. One is never at ease; there is a sense of constant interruption. One sits immobile, but does not rest. During an afternoon of wind watching, Duenwald wrote to his wife: "As I have said before, this is like putting in time in a jail - a very uncomfortable jail. I am sure that no one could design a system of confinement which could rival this for punishment." Seventy days earlier, on a truck crossing the plains of India, he had written, "No adventure is good unless you pay the price. Painful experiences make an adventure worthwhile." No one was ready to argue that this adventure was not worthwhile.

The exercise in getting to a meal, and the talk during it were as nourishing as the food itself. The high altitude food was disappointing; many of the goodies we sought down below were unattractive at altitude. There was for once too little starch, and not enough tea. We craved butter and we needed quantities of hard candy to soothe sore throats. We lived on soup, rice, cheese, and dry meat, with some puddings and chocolate. Canned cakes and canned cookies were the backbone of the diet, but they never lasted long. Fluids were a constant problem. Supplies of clean ice and snow within an arm's reach of the tent door were soon depleted, leaving the choice of roping up to forage or using off-color snow. Cooking was a protracted operation, and a dangerous one, because precariously balanced pots could easily be knocked over, and often were. There was little room and no flat space for cooking, so a delicate pot-on-stove arrangement had to be balanced on a rickety base and shored up by piles of equipment, held by hand, or both. If one opened the tent a bit for ventilation, spindrift snow poured in; if one left it closed, steam would condense heavily on the nylon and then rain inside. In compromise, we generally got both spindrift and condensation. Small, lightweight pressure cookers were a great help at altitudes where an open pot of water boils at less than 150 degrees, turning food to mush before it can cook properly. But a pressure cooker which blows a valve or is accidentally opened inside can create a blizzard of its own when the steam condenses on the tent walls.

HUDDLEHUDDLED in the tent at Camp II, the climbers talked of everything but the mountain, and every kind of weather but wind. They hiked, sailed, cut trees, harvested wheat, dined on haute cuisine, drank heady old wines and planted new grapes. Sonam Girmi took them to Namche Bazaar, to his wife and sons and cattle. They listened to Sonam Girmi's tales of eighteen other expeditions, and of his dreams for his eldest son, destined for a post in Kathmandu's government bureaucracy. The wind drew them back to the Himalaya. Sonam Girmi told them of the spirits of mountains, of the power of mountains over men. He liked the Dhaulagiri region, because he had always had good luck there, on Annapurna and on Tukche Peak, but most Sherpas were suspicious of the place - it was too far from home, the weather was always bad, and the winds blew without reason, Dhaulagiri would let us reach the summit, he was confident of that, but why did we want to try for a multiple ascent? That he did not understand, nor did he think the mountain understood.

Each day dawned frustratingly clear; the features of the mountain were sharp, but the wind continued. The aluminum poles and fiberglass wands in the tents broke one by one, so the tents became amorphous bags of red nylon, alternately puffing out like balloons and slapping tightly down around those inside. On the days when the wind was strongest, Sonam Girmi did not leave his tent. The wind was deafening, but through its noise, Duenwald, Harvard, and Thompson could hear the chant of Sonam Girmi's prayers. His steady low monotone was set against the high erratic fury of the wind; the prayers had a patience and serenity that balanced the wind's aggressiveness.

ON the night of May 5, the wind blew as it had never done before. It seemed to skin the mountain, and Camp II, exposed as it was, was blown apart. Sleep was normally an uneasy proposition there, but that night no one even tried to sleep, Duenwald and Harvard sat fully clothed and booted as their tent danced on its tiny platform, ominously close to the void. They were of course roped, but they were painfully aware of the weakness of their anchor. The other two tents fared little better. In the morning, the four climbers in Camp II were as exhausted as after a hard day's work, and the camp was a shambles cooking was impossible. Thompson couldn't talk, Duenwald had mi was ill-at-ease. The morning radio contact was brief, and discouraging: Camp III couldn't move, but would try if the wind died; Camp I was freshly buried, but had ample healthy manpower; at Base Camp all was serene. Camp II was a blown-up link in the chain. The three sahibs and the sirdar conferred, and quickly, dully, agreed to go down to be replaced. Their role was support, but on the morning of the sixth, they „ere barely able to support themselves. They had all been strong proponents of the group goal, so the pain of retreating was not personally unbearable. Actually, the pain was nonexistent: when Duenwald asked, rhetorically, if everone felt all right, Harvard replied, "Jeffrey, I don't feel a thing...."

The wind did drop later in the day at Camp III, so Roskelley and Ngawang Samden set out to probe the route above the May 2 high point. "The cold was extreme, but we had had enough of sitting in tents," Roskelley recalled. They rounded a rock buttress and climbed up the wide gully using the buried fixed ropes. From the ridge at the head of the gully, they began a long climb to the junction of the upper ribs of the southeast ridge and the northeast spur. They cached loads for Camp IV at the site of the Swiss high camp, a precarious rocky ledge, and investigated a site for Camp IV, a sheltered step about two hundred feet above, at 25,700 feet.

Their return to Camp III was joyous, but the joy was short-lived: the evening brought the return of the winds, and everyone was pinned down again. At Base Camp, the team just down from Camp II was set to enjoy a night of comfort, of actually lying down to sleep, of being able to take boots off, of warmth and silence and peace. However, a sudden night storm dropped two feet of heavy wet snow on the col, and crushed two tents before their sleeping occupants could react. Groggy climbers woke up to the weight of snow and wet nylon as the tents caved in, struggled for boots, pants, and mittens in a close darkness, then cut the tents open, dug themselves out, and staggered into the storm to look for other shelter. After a miserable search, they found a place in the frozen muck on the cooktent floor.

Morrissey returned to Base Camp with a bronchial infection, and an unexplained ability to cough up pieces of his pharynx. He would start to gag, and then work up a chunk of the stuff, roll it around in his mouth, spit it into his hand and proceed to examine it with clinical sang-froid. That was all right, but he insisted on showing it to his friends, and speculating on just what part of his respiratory system had produced it. He had his throat and the specimens photographed. He stored one piece in a film can for study after the expedition, but forgot about it, put a roll of exposed film in the can and sent the whole thing off with a shipment to National Geographic. Lyman continued to have trouble with his legs, a problem diagnosed as neuritis. Both Ang Dawa and Gyaltzen were under the weather, with coughs, headaches, sore throats, and general malaise, and Sonam Tsering was beginning to show the emotional strain of his physical disability. Above Base, the climbers were beginning to show clear signs of physical wear. Psychologically, most people were convinced that everyone else was slowly losing his mind, but that it would be a breach of etiquette to tell them so. The doctors recognized definite symptoms, but the only illness was altitude, and the only prescription would be: "Go down."

THE storms continued. On the night of May 8, Langbauer woke at Camp I in a fit of coughing. He was sharing a close, stuffy tent with Smith; snow had piled around the tent, sealing off circulation. The coughing was followed by hyperventilation, which brought on coughing again. The cycle accelerated, and increased in severity. Prostrate, Langbauer perceived the symptoms of shock develop in himself; he was suddenly cold, and on the verge of blacking out. Smith called to Lev and Fear in a near-by tent. They brought an oxygen system from the snow cave, and Langbauer was given oxygen at four liters per minute to steady his breathing. No one was sure what the trouble was, but any therapy at high altitude involves oxygen, and Langbauer's gasping needed quick attention. He warmed quickly, and his breathing regularized as his cyanotic blue skin turned a healthier pink. He slept well on two liters a minute that night, and went down to Base Camp the next day. After a clinical conference which considered the problems of too much carbon dioxide (from the climbers), too much carbon monoxide (from the stoves), and too little fresh air (the tent was nearly buried) and too little oxygen in the air anyway, the medical community of three physicians, a veterinarian, and an ex-army medic collectively shrugged: "It's the altitude."

On the morning of the ninth, Bech in Camp III woke again with a troublesome earache. It had begun a few days earlier as he sat waiting for good weather. He had tried antibiotics, but the pain grew worse, and he now had to admit it was not going to go away. Bech, a concert violist, could not afford to gamble with his hearing. Resignedly, he descended to base camp, where he announced that he had come down in order to conserve supplies at Camp HI while the bad weather lasted. On examination, Rennie found a severe middle-ear infection on its way from bad to worse. It was a painful disappointment for everyone, and a personal disaster for Bech; he had worked harder than anyone on the spur. His determination gave strength to others, and his cheer was an endless resource. Bech, more than anyone else, symbolized the efforts on the spur.

On the tenth the weather finally broke, with a warm, windless day. In Camp III, Roskelley, Reichardt, and Ngawang Samden made loads of sleeping bags, tents, and ropes; Pasang Tenzing and Nang Tenzing loaded up the Camp IV food bag, stoves, fuels and ensolite tent floors, and the five started up. Roskelley and Ngawang Samden, in the lead, followed the route they had found eight days before to the cache at their high point. On the left they passed the 1970 Japanese high camp, and farther on, the 1960 Swiss bivouac-tent site. They reflected on the available sites for Camp IV, choosing a sheltered snow bowl, flat enough to pitch a tent in comfort and reminiscent of the soft mountains of the American Northwest. Reichardt, Roskelley, and Nawang Samden pitched a single tent while Pasang Tenzing and Nang Tenzing scurried back to Camp III in the face of the afternoon storm.

That night, they enjoyed the goodies in a special high altitude food bag: tea, soup, butter, mashed potatoes, and savory, if not particularly digestible, freeze-dried fruit, vegetables, and chili. Outside, the Dhaulagiri winds returned, and with them, new snow.

"The eleventh never dawned," Roskelley later wrote. From top to bottom the mountain was battered by wind. The three were comfortable in the tent, moving little, talking less: Reichardt was forced into silent reverie by laryngitis, Ngawang Samden is a taciturn man, and Roskelley was not inclined to monologue. Reichardt began to suffer a slight loss of balance. When he was not concentrating, he would lean slightly to one side. Imbalance made walking difficult, and it was a threat to the stability of teacups and soupbowls in his hands. That evening, Bech and Morrissey gave them an optimistic weather forecast based more on hope than conviction. The weather simply had to let them go; they could not wait at nearly twenty-six thousand feet for long. The good weather prediction was taken as gospel in Camp IV because that was the easiest way to take it. They went to bed early and slept well.

"HOORAy! Hooray! for the twelfth of May. Outdoor screwing starts today!" Rennie cheerfully greeted Pinzo at Base Camp the next morning. "Tea, sahib?" ventured Pinzo, waist-deep in yesterday's new snow, as he looked down into Rennie's tent-pit. "They're going to make the summit today," said Bech from a neighboring pit. In a third, Morrissey argued briefly with Roskelley at Camp IV over whether carrying a radio to the summit would be an act of desecration; more to the point, thought Roskelley, a radio weighs more than a pound. Morrissey gave up, wished them luck, and sent the blessing and hopes of the rest of the climbers in camp. Beyond that, they would be alone.

The authors: Andrew Harvard '71 in the snows of Dhaulagiri and Todd Thompson '70 under an umbrella in Kathmandu.

The authors: Andrew Harvard '71 in the snows of Dhaulagiri and Todd Thompson '70 under an umbrella in Kathmandu.

"Mountain of Storms" is excerpted from the authors'book of the same title, to be published jointly this monthby Chelsea House and New York University Press. AndrewHarvard is a forester in Vermont; Todd Thompson isa banker in Panama.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"THE KINGDOM OF GOD HAS COME"

October 1974 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1974 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE MINER -

Article

ArticleDr. Seuss' Professor

October 1974

Features

-

Cover Story

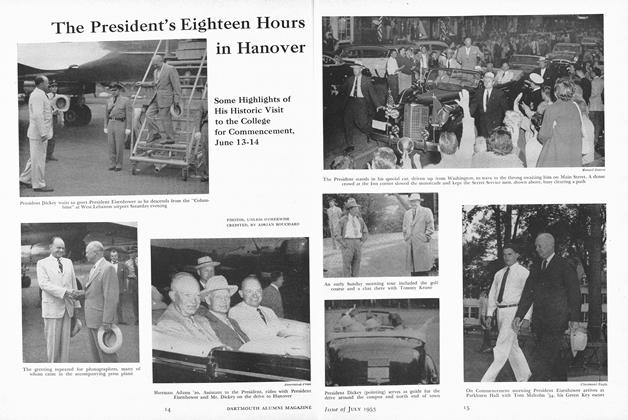

Cover StoryThe President's Eighteen Hours in Hanover

July 1953 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Feature

FeatureCampbell’s Coup

Jan/Feb 2010 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1958 By J.B.F. -

Feature

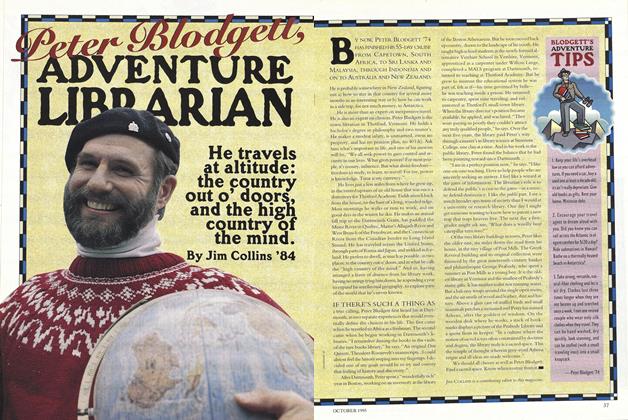

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

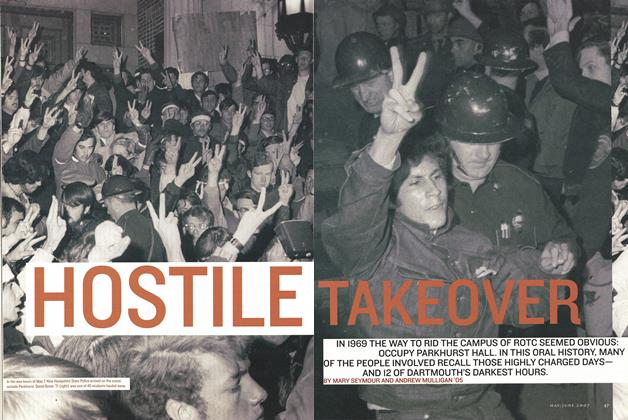

FeatureHostile Takeover

May/June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05 -

Feature

FeatureBards in a Barren Desert

November 1982 By Stephen Geller '62