Some thoughts on man, science, and the humanities in a technological society

WHY do alumni, in a technological age, support an institution which belittles practicality? This demands an answer, yet to respond to the question as stated would be to grant its assumption that the university does indeed belittle practicality. Perhaps it does to some extent, but it certainly does not do this monolithically. Nor is it very helpful to suggest that only the humanities exult in irrelevance, while the sciences keep pulling us in the direction of the trade school. This is so misleading that I am going to argue the precise opposite, claiming that science and technology tend to be self-contained, divorced from life, whereas the humanities are in fruitful contact with the outside world. In any case, the most responsible way to answer the question posed is not to defend a supposedly-monolithic Dartmouth against accusations from the prac- tical world outside, but rather to investigate the split which exists within higher education iteslf, and to suggest a remedy.

To do this we must begin with the most fundamental of all questions: What is man? What does it mean to be human? I raise this not only because it is always an interesting problem, but because liberal education, which originated in the Renaissance, was predicated on a very clear and specific conception of the nature of humanity. It is hardly surprising that the Renaissance, which, following a period intensely Christian, rediscovered the pagan culture of Greece, should have defined man in terms which synthesized the Christian and pagan views, achieving a balance. The doctrine of humanism which originated in the Renaissance asserted that man, through his rationality, could stand on his own two feet and solve his problems, that he no longer had to cringe before God and bewail his sinfulness or inadequacy. But this optimism was carried only so far. Man was restored the dignity he had enjoyed in the pagan conception, but he was not transformed into a god in Renaissance times (any more than he had been in pagan times). Indeed, the very definition of man dwelt not so much on what he was as on what he was not. In simplest terms, man was defined as that creature which is more than a beast and less than an angel. Sir Thomas Browne, in the 17th century, called him "that great and true Amphibium," able to exist in two different realms but not belonging exclusively to either.

Note that the definition was primarily cultural rather than biological. That is why the real question was not "What constitutes the genus homo?" but rather "What constitutes the homo humanus, the truly 'human' man?" The answer was: That creature which, on the one hand, has moral values, urbanity, learning, technical skill, free will, responsibility (all of which are missing in beasts, or for that matter in the barbarian, the homo barbarus), and, on the other hand, that creature which is characterized by fallibility, transience, frailty, mortality (all of which are missing in angels or gods).

Renaissance thinkers did not have to rely on Christianity to remind them of man's frailty; pagan thought had already set out the limitations of man as well as extolling his capabilities. A single text will suffice here as an example: the famous chorus from Sophocles' Antigone. Paraphrased and condensed, it goes something like this:

There are many wonders in the world, but none so wonderful as man.

He is the being who knows how to cross the sea despite storms,

He is the being who torments earth with his furrows year in year out.

He traps the birds of the air and beasts of the forest.

He is a master of ingenuity. With his art he tames the savage bull, and breaks the rough-maned horse to bear the bit.

Speech, wind-swift thought, aspirations which give birth to cities - all this he has taught himself,

And he has made provision against rain, and freezing winds.

He is well armed against whatever the future may bring, including foul diseases, Yet for death he will never find a cure.

Christianity was not needed to remind the Renaissance of man's frailty, but the Renaissance nevertheless invoked Christianity in this regard. It is important for us to remember that Renaissance humanism (out of which came liberal education) was not an attitude that wished to replace one thing with something else. On the contrary, it was an attitude which asked men to broaden their perspective, to be open to all truth, rather than to exclude. If Christianity had tried to exclude paganism, that was no reason why humanism should try to exclude Christianity. The real move was toward synthesis, and the humanistic posture was that of skepticism in its root meaning: thoughtfulness, openness to all opinions, distrust of rigidity and dogma.

Liberal education issued from this synthesis of Greek and Christian thought. The word "liberal," here, has a very straight-forward meaning. Positively, it means "munificent," "expanded in spirit or scope" - as in the phrase, "He made a liberal contribution to the Alumni Fund." Negatively, it means: "not bigoted, dogmatic or narrow, not willing to limit free inquiry." The liberal arts were thought to be appropriate for the homo humanus with his broad, tolerant mind. They formed a curriculum characterized by breadth and diversity rather than narrowness, a curriculum which we have inherited. A liberal education taught broad-minded men about themselves: about their capabilities, as evidenced in mathematics and the natural sciences for example, and also about their limitations, as asserted in Scripture, literature, and philosophy.

The synthesis was not only beautiful, it was staggeringly important in the history of mankind, because this fusion reaction in the cultural sphere released prodigious amounts of energy. One especially noble fruit of this synthesis was John Milton's Paradise Lost, which is appropriate to invoke here not simply because most Dart- mouth alumni have presumably read it (thanks to the conservative humanism of our English Department) but because this epic poem fuses science and art, the pagan and the Christian, and presents to us precisely the view of homo humanus that I have elaborated: a creature delicately placed between beast and angel, more than the first, less than the second. Here is Milton describing the sixth and last day of creation:

There wanted yet the masterwork ... ... a creature who, not prone and brute as other creatures, but endued with sanctity of reason, might ... govern the rest, self-knowing ... but grateful to acknowledge whence his good descends....

The point of Milton's poem is that Adam and Eve's sin, their frailty, far from confirming worthlessness, or the degenerate nature of mankind, enables our First Parents to have a re-naissance as responsible creatures with power over their own destinies (short of power over death). God kicks them out of Paradise, where everything is provided, and says in effect: Take care of yourselves, learn how to cross the sea in storms, to till the earth, trap birds of the air and beasts of the forest, tame the horse, give birth to cities, conquer disease.

Milton's Adam and Eve will do all this - because they are we: the culture which took its impetus from the Renaissance - but they will do it always grateful to acknowledge whence their good descends. They are still frail; they never confuse themselves with angels or with God. They combine scientific and humanistic pursuits without any uneasiness because their purpose in scientific endeavor is neither to subdue the earth nor to magnify their own intellectual powers, but instead to acknowledge their limitations in contrast to the Deity who so graciously allows them to poke around in the marvels of the created universe.

WE start with a synthesis and with a coherent pedagogical ideal called liberal education, based on a definition of homo humanus. What happened to it? Inevitably, certain separations began to develop. Scholarship broke into two hemispheres: the world of natural phenomena accessible to our senses, and the world of culture, i.e. of records left by man. The first - nature - became the province of science; the second - culture - the province of the humanities. But the method of each remained similar at first, as did the goal. The method was observation, whether of natural phenomena or of human records. The goal in each case was to make sense of the material observed - to order it.

So far so good. But then, beginning certainly as far back as Descartes' Discoursde la methode (1637), the seeds of a more fundamental sundering were planted. For a convenient analysis one may turn to José Ortega y Gasset's well known essay "Relativism and Rationalism," where Descartes' insistence that man has his being only in his reason - Cogito ergo sum, "I think, therefore I am" - is taken as the wedge which drove man's thinking self apart from his practical relations with the outside world.

Descartes reduced man's knowable essence to "pure intellection," but this pure intellection is (in Ortega's words) "nothing else but our understanding functioning in the void, ... in contact with itself, and controlled by its own internal standards." Ortega concludes that "rationalism, for the sake of retaining truth, renounces life." Why? Because "truth ... must be complete in itself and invariable," whereas life is "essentially mutable and varies from individual to individual, from race to race, and from period to period." We end with rationalism as a static principle, nature as a dynamic one, and the two divided.

As the antagonistic division between rationality and nature widened, increasing at the same time the distance between the humanities and the sciences, an interesting reversal occurred. The humanities, rather than the sciences, became in some sense the guardians and defenders of nature.

This paradoxical reversal is very evident in our own day. It was caused in part by the scientific perception that nature is a dynamic, evolving flux rather than a mathematically exact mechanism. It also arose because the sciences and humanities, after the Renaissance, began to face in such decisively opposite directions, temporally, with science becoming increasingly interested in the future whereas the humanities looked exclusively at the past. It has been said that science's job is to make a cosmos of nature. Using slightly different language, we could say that its job is to make systems or models whose truth will be measured against future occurrences of the natural phenomena they systematize. Science detaches itself from the dynamic present - from the actual flow of time - in order to build static systems outside of time. It looks to the future and tries to bring it under control - under laws which apply to past, present and future. The humanities do just the reverse. As the art historian Erwin Panofsky has stated, they look to the past and "endow static records with dynamic life."

It ought to have been science that dealt with and understood nature's dynamism, while the humanities dealt with the static, non-natural records left by man. Instead, we arrive at a situation in which (at least according to many humanists) science kills nature by reducing its dynamism to a lifeless stasis in the interests of truth, whereas the humanities resurrect it by operating in terms of a dynamic mental process rather than a static mental possession. This perception leads humanists to an increasing distrust of rationality, and encourages them to attack rationality's

systems as life-destroying rather than lifeenhancing. The humanities' antagonism toward science can be seen again and again in modern literature. A blatant and simpleminded example is the following conversation in Kazantzakis' novel Freedom or Death, where one Cretan questions another who has just returned from Western Europe:

"Are they believers?"

"They believe in a new godhead ... "

"In what?"

"In science."

"Mind without soul. In the devil, that means. ... We Cretans ... have a higher belief than in the individual, the belief in tears and sacrifice. We are still under the sign of God."

The rest of the novel makes clear that mind and rationality, associated here with the deyil, must be rejected because they inhibit the dynamic, living, creative soul.

For an articulation of the rationalistic, scientific mentality being attacked here, we could turn to the character Settembrini in Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain. But there is no need to range so far abroad as Mann's Davos. John Kemeny, in Manand the Computer, calls for "a model of the operation of Dartmouth College," a model not only of the various sectors of College organization, but also - note well - of the "dynamic interrelationships" among them. In other words (and this is perfectly orthodox science) he desires to take something characterized by motion and time, and to fix it, render it static, so that (a) we might produce this model for the cosmos of Dartmouth College, and (b) with the model produced we might better control the future of the College. This, the humanist would argue, is turning life into death. Since Dartmouth College is dynamic, its future can never conform to a model. Indeed the better the model - the closer it represents the situation from which it was drawn - the less likely that any future situation could conform to it, except after Procrustean stretching or amputation. Creativity is sacrificed; the very dynamic interrelationships that were to be represented in the model are robbed of their dynamism.

Everything is now topsy-turvy. We begin with one distortion of human nature in the Middle Ages, where man's frailty and transience are emphasized and his creativity, grace, dignity and problem-solving capacity are suppressed. Out of this deadness we experience a rebirth in the Renaissance: the static becomes dynamic once more. Man's frailty is no longer over-emphasized; his capabilities explode as though in some nuclear reaction, releasing the enormous energy which created industrial Europe and America. Yet now, at least according to many humanists, rationality - the very force which previously effected the rebirth and remedied the deadening medieval distortion of human nature - has ironically entered the service of death and the devil, producing an opposite and equally deadening distortion.

One could sum this up as a charge which the humanities fire at science: the charge of forcing life into a Procrustean bed of rationality, thereby denying the dynamic flux which is life's essence.

There are of course other charges as well. I shall discuss three of them, briefly. The first may be called "millenarianism." The Renaissance, though at first attempting to maintain a balance between man's capabilities and his frailty, set in motion a surge of optimism. Science (joined by the humanities for a time) rejected as outrageous the medieval insistence on Original Sin. The Renaissance discovery of ancient Greece threw such sunlight and warmth into the medieval gloom that it became easy to believe in a golden age of mankind in the past, and then to project that golden age into the future - something which science continues to do today. This optimism is often curiously self-contradictory. On the one hand, it asserts that "unaccommodated man" can never achieve the golden age; on the other, it asserts that with tools or systems (which, after all, can only be as good as the men who design and operate them) everything will be all right. "To make service institutions perform," says Peter Drucker, "... does not require 'great men.' It requires, instead, a system...." John Kemeny, in his peroration to Man and theComputer, makes this even more explicit:

The best-intentioned people, if they lack the technical expertise and the tools to achieve our goals, can make the situation worse instead of better. Therefore we must look to the coming of a new man-computer partnership to provide the means which, combined with sufficient concern by men for their fellow men and future generations, can hopefully bring about a new golden age for mankind.

We have here a moral and scientific optimism which is obviously noble and which, we all must admit, has made possible our present industrial and democratic society. Yet the humanities insist that this same optimism, though undoubtedly creative and liberating during a given period in history, is now an inhibitor. Why? Because it distorts the human condition, blinding us to our true constitution. Strangely, though science and rationality sought to dispel medieval ignorance, superstitution and myth, they have nevertheless reinforced their own myth of the golden age. Science dreams of transforming homo humanus into homodivinus.

The next charge (the opposite side of the coin from millenarianism) is that science uses its immense powers consciously and unconsciously for evil.

Science itself, of course, is aware of this, and disturbed. But whereas the scientific community still tends to believe that its evil manifestations are perversions which can be eliminated, we humanists tend to assert (rather gloomily, it is true) that only if scientists were 100 per cent angels would they cease to do evil. The scientist will retort that the pot is calling the kettle black. Obviously, humanists are no better morally or intellectually than scientists; probably they are worse. But humanists do not wish to possess or to master. We don't reach out beyond ourselves but instead are reflexive, examining the outside world primarily to learn about ourselves. This serves to neutralize our malignance and render us comparatively benign. In any case, humanists make bold to charge that science has been and will continue to be extremely dangerous. More boldly still, we assert that science, to a greater degree than the humanities, confirms that man is dangerous - a creature peculiarly self-destructive. George Bernard Shaw's Devil (in Man and Superman) was saying this as long ago as 1903:

The peasant I tempt today eats and drinks what was eaten and drunk by the peasants of ten thousand years ago; and the house he lives in has not altered as much in a thousand centuries as the fashion of a lady's bonnet in a score of weeks. But when he goes out to slay, he carries a marvel of mechanism that lets loose at the touch of his finger all the hidden molecular energies, and leaves the javelin, the arrow, the blowpipe of his fathers far behind. In the arts of peace Man is a bungler. I have seen his cotton factories and the like.... I know his clumsy typewriters and bungling locomotives and tedious bicycles: they are toys compared to the Maxim gun, the submarine torpedo boat. There is nothing in Man's industrial machinery but his greed and sloth: his heart is in his weapons....

Shaw's Devil ranges back and forth over history, attacking the human mind in prescientific as well as scientific ages. Man himself, not science per se, is the villain; yet the implication is clear that science and the resulting technology intensify this villainy. The scientist E. Cantore adds that before the advent of science it was perhaps easier for us to have illusions about ourselves. We could try to explain away our fallibility and evil by pleading ignorance and powerlessness. "But the advent of science, by giving man so much knowledge and power, has mercilessly expose the dishonesty of all such inter-pretations." Science confirms to the humanist that man errs not only by attempting to be more than human but by allowing himself to be less. To succeed as that great and true amphibium homohumanus means to walk a tightrope between angel and beast.

How do these accusations against science relate to the problem of practicality versus irrelevance? I began with Ortega's analysis, whereby scientists are seen as divorced from nature precisely because of their devotion to static, timeless truth. On the other hand, it is hard to think of science as impractical and inactive after all that has been said about its effort to provide models verifiable in the future, or about technology's attempts to mold the future according to these models. This certainly sounds like action. Conversely, I spoke of the humanities as reflexive, turning back upon themselves for self-knowledge and that certainly sounds like inaction.

Clearly, I shall have to define "action" in a careful way. Let it be called "a dynamic engagement of a human being with something outside himself, an engagement which affects both the subject and the object, and indeed obscures the distinction between the two."

Now this is precisely what fails to happen in science. Despite the Heisenberg Principle, the most basic scientific mentality continues to be that of separation between the investigator and the phenomenon being investigated. The scientist must struggle to be objective, which means he must avoid adulterating his observations with subjective factors. This same divorce between subject and object tends to maintain itself if and when the scientific model or system is applied practically. The technologist proceeds to master reality in a state of mind whereby reality is something outside, not including or affecting either himself or the system which is being used.

Here, I suggest, we encounter "pure learning." The system is impenetrable, immutable hermetically sealed against everything outside - mastering, but refusing to be mastered in turn, i.e. refusing the dynamic, mutual engagement with the outside that is the essence of action as I have defined it. This is why science and technology have spread ugliness over the earth, constructed cities which are degrading, turned workers into automatons, and invented diabolic forces of destruction: because true action involves sensitivity and flexibility; it is not the imposition of thought upon the future or upon the environment, but the constant modification of both thought and the environment by means of dynamic-interpenetration. Science, because it tends to maintain the autonomy and separation of its rational conclusions even while reaching out beyond itself, via technology, in order to "contact" the outside world, only masquerades at acting.

In the humanities we reach outward in order to reach inward again. The word "reflexive" is worth repeating. We examine objects outside us as a way of learning about ourselves. There is no divorce between subject and object. As James Joyce said, we walk through others but always meet ourselves. Mastery is minimized, sensitivity and celebration are maximized. In reading a book, for exampLe, we do not stand outside and attempt to understand this "phenomenon" as separate from ourselves. Instead, we revivify its dead letters by reliving its experiences in our imaginations. In the process the book - supposedly the "object" being investigated or observed by us - takes on an active role. It affects our sensibilities, works on us instead of vice versa, acts as subject while we become the object! Any clear distinction between subject and object withers away. Moreover, the contact is dynamic as well as sensitive. A second reading is never the same as a first reading. The book is not a static model or system working on us, nor do we bring static models or systems of thought to bear on the book (unless we have been corrupted by science). Each contact is different, and each affects both partners, changing them in different ways. This is action, true action, because it is an application of the mind to life (books are part of life) in a truly symbiotic way involving a warm, living contact in which each partner needs the other.

In considering the position of liberal education in technological society, it is inadequate to accuse the humanities of devaluing action and of retreating into irrelevant contemplation. This is not the problem. The problem, rather, is that scientific and technological endeavors in the university (and outside it) are not sufficiently reflexive. Maintaining the split between subject and object as they are wont to do, maintaining the unfortunate goal of mastery and possession, they fail to see that the attempt to make a cosmos of nature, just like the humanists' attempt to make a cosmos of culture, is most importantly a process - more precisely, a process by which man discovers himself. Our mistake has been to place value outside of the process which seeks value.

Scholarship, both scientific and humanistic, ought to be a ruse, a game played with nature and culture, future and past, as an indirect way of coming back to the only question worth asking: What is man? This is what liberal education, that product of a broad conception of man originating in the Renaissance, is meant to do. Being liberal, i.e. of a breadth befitting the homo humanus, it is meant to do this through scientific as well as humanistic investigation. We shall therefore affirm, parodying Thomas Arnold, that a liberal education without the sciences must be, in any technological country, a contradiction in terms. Science and technology do have an essential, continuing role to play in liberal education - provided that the major lesson they teach, however indirectly, is that man is a creature both staggeringly ingenious and staggeringly dangerous: too good to be a beast, too frail and corrupt to be an angel. If they do this - and there are indications that more scientists and even technologists are beginning to think reflexively then - we shall see a university in which the scientific faculties, as well as the humanistic ones, advocate a practicality compatible with the liberal assumptions we have inherited.

Far from belittling practicality, we shall tell our graduating seniors (as we expel them from Paradise) to go out and discover the meaning of their own humanity in the best manner possible: by active engagement in life's practical affairs. In this way we shall avoid the sterile irrelevance so worrisome to alumni while at the same time minimizing the type of inhuman practicality that ties life into a straitjacket in the name of objective truth. Insofar as we attempt to maintain the goals of liberal education by these means we ought to deserve support, especially in a technological age.

"Science only masquerades at acting. In thehumanities we reach outward...."

Peter Bien, a member of the EnglishDepartment since 1961, was recentlynamed Dartmouth's first Ted and HelenGeisel Third Century Professor in theHumanities. This article was occasionedby a debate between President Kemenyand him at an alumni seminar last spring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"THE KINGDOM OF GOD HAS COME"

October 1974 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMountain of Storms

October 1974 By ANDREW HARVARD, TODD THOMPSON -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1974 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE MINER -

Article

ArticleDr. Seuss' Professor

October 1974

Features

-

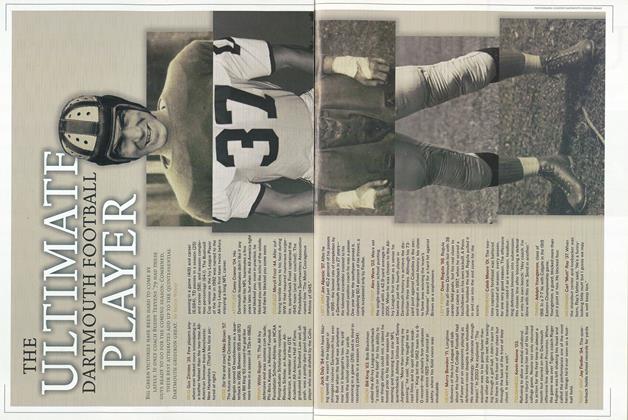

Feature

FeatureThe Ultimate Dartmouth Football Player

Sept/Oct 2007 By Bruce Wood -

Cover Story

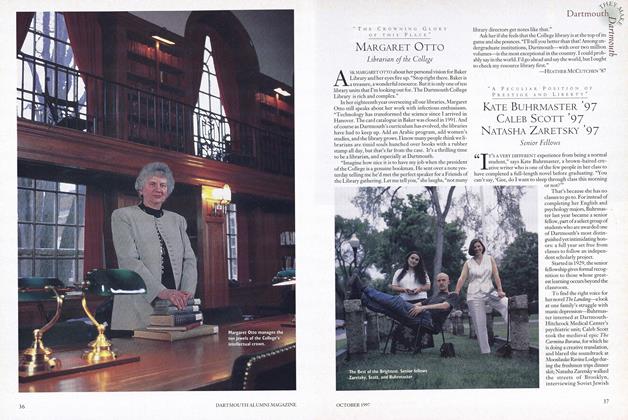

Cover StoryMargaret Otto

OCTOBER 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow Does Our Garden Grow?

Nov/Dec 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2008 By JOSEPH MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureLet There Be Color

May/June 2013 By Sean Plottner -

Feature

FeatureBusiness as a Social Service

October 1956 By THE HON. RALPH E. FLANDERS, LL.D. '51, U.S. SENATOR FROM VERMONT