The automobile,like the Gothic cathedral,dominated an artistic culture.Perhaps it was eventhe supreme creationof an era.

NOT long ago, while reading an essay by the French literary critic Roland Barthes, I encountered the following passage: "I think that cars today are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals. I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image, if not in usage, by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object."

As a historian of medieval art, who views largely with suspicion-albeit with occasional interest - the course of Western culture since about the year 1300, I was more than mildly provoked by Barthes' blunt analogy. This outrageous formulation exceeded even the widest known limits of Gallic intellectual perversity. Not even America's own enfant terrible, Tom Wolfe, in The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, dared venture into such blasphemy with his "pop-chic" discourses on Versailles and Las Vegas.

Perhaps it should have been left to lie, but beneath Barthes' threatening thesis lurked a nagging soupcon of authenticity, begging to be put to the test. If medieval saints could find God in a walnut, could I not at least discover Chartres in a Chevrolet?

The difficulty, however, in demonstrating valid connections between monuments of the past and artifacts of modern popular culture is all too apparent. For the most part we lack both the conceptual skills and analytical tools to undertake comparative evaluations of such widely disparate phenomena as churches and cars. How does one, in short, get at these matters (assuming there is any need) without resorting to mumbo jumbo and incantation?

For the purposes of this tentative inquiry a possible guide was discovered in a number of old issues of the pre-Luce Life and TheSaturday Evening Post, where a rich hoard of automobile imagery was excavated from a past in many ways remoter to me than the creation of the first Gothic cathedrals in the second quarter of the 12th century. These early cars and their advertisements (for this is the medium through which they were most accessible and in some instances the only visible evidence of no longer extant models) afforded a range of provocative insights. The additional fact that cars and advertising also shared a common infancy and adolescence (did advertising make the auto or vice versa?) brought to light several instructive corollaries as well as new and unanticipated sources of aesthetic pleasure.

AN ad for the Columbia "Automobile" (1) provides A characteristic example of early advertising at a time when such generic terms as "electrobat" and "buggyaut" were M vogue. Small in scale and emphatically graphic in presentation, the "electric phaeton" occupies less than a quarter of the space of the ad, the remainder being devoted to a variety of generous claims for the excellence of the vehicle. Stylistically, the early vehicles, as their names imply, depart only marginally from the horse carriages of the era. In a formal, as well as chronological sense, these early auto designs and the ad-images that promote them represent archaic phases of their respective arts.

A 1905 ad for Oldsmobile (2) is interesting, not only for the "advanced" automobile styling (mainly visible in the extruded hood required to house the engine in front of the carriage), but also for the quality of the advertising image. For the first time a major artist - in this instance Edward Penfield, the art editor of Harper's and the foremost illustrator of the period - executed the pictorial design which occupies roughly a third of the full-page ad. Though integrated neither formally nor conceptually with the text, Penfield's winsome image does much to combat the verbal bias of most early American advertising.

Based on the flat, patterned designs of the great French poster-makers Cheret and Toulouse-Lautrec, Penfield's design depicts not only chauffeuse and passenger, but attempts by way of swirls of snow and a few directional lines to suggest motion. The result, happily enough, is a thoroughly static image embodying the finest decorative traditions of the era.

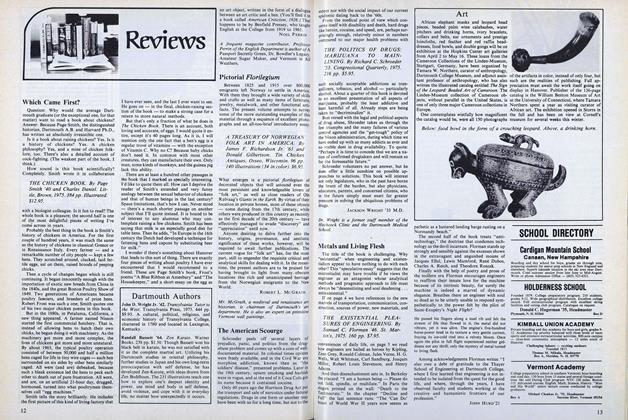

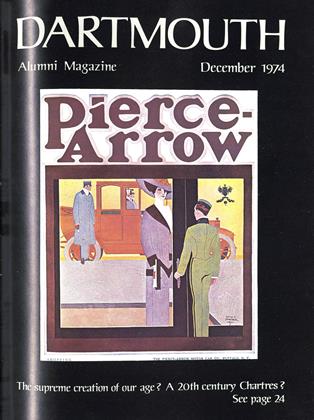

Somewhat more ambitious solutions to the problem of representing speed are a Pierce Arrow ad (3) of 1908 and one for Baker Electrics (4) of the following year. Blurred wheels and a heightened awareness of the spatial setting lend these images a sense of motion. These full-page color lithographs also dominate for the first time the text which has migrated largely to the bottom of the page. Commissioned from the New York artist Louis Fancher, the Pierce Arrow ad introduces a foreshortened view of the vehicle which is appropriately posed against Augustus St. Gaudens' Sherman Memorial in Grand Union Plaza, one of the most fashionable monuments of the Belle Epoque. For all their apparent dynamism, however, these cars are simultaneously rooted in static immobility,' a fact which, if anything, enhances their appeal for the modern viewer.

Also from 1909 is Fancher's lithograph (5) of a figure alighting from a Pierce Arrow before the steps of the Columbia University Library. Here the vehicle and passengers, together with the ambience, carry the full freight of the ad's meaning, all text, save the logo, having been abandoned.

There is also a new penchant for flattening the image through the partial suppression of spatial and atmospheric properties, a direction that attains its culmination in an exquisite Pierce Arrow ad (6) for 1911. In this splendidly conceived design, Fancher - an artist whose undeserved obscurity is exceeded only by his keen eye for the decorative potential of advertising - has eliminated all spatial references in favor of abstraction and graphic economy. Also belonging to this family of advertisements is an anonymous lithograph (7) from Life of January 1910. Though largely indebted to Charles Dana Gibson for the square-jawed image of Yankee masculinity, the artist's truncated and strongly foreshortened auto is closer in spirit to Fancher's pioneer vision of fashionable elegance.

An important pictorial alternative to these snobbish conventions is provided by William Harden Foster's painting (8) of 1910, which was frequently reproduced for Oldsmobile. In this dynamic ad a violently foreshortened car leaps urgently out of the Page at the viewer. At least two years before the famous photographs of racing cars by the Frenchman Jacques Lartigue and the pictorial experiments of the Italian Futurists, Foster has Actively resolved the problem of the representation of automotive speed.

A classic" of automotive design as well as advertising layout is the image of the 1913 Packard (9). The artist, the etcher E. Horter, situates the vehicle directly in front of the Arch of Septimis Severus in Rome. Possibly alluding to the Imperial quadrigas of ancient Roma, Horter sets the Packard at right angles to the famed via sacra traversing the Forum. At thebottom of the ad appears the first of the great automobile slogans, "Ask the Man Who Owns One."

A renewed invasion of the pictorial field by textual matter can be observed in a 1916 ad for Simplex (10). In this respect a harbinger of future advertising trends, the ad also reveals a concern with military affairs on the eve of America's entry into the Great War. The curved forms of the Simplex is also an example of the new automotive "streamlining" just coming into vogue.

On the whole there are relatively few changes in automobile design between 1920 and 1930. It is a period of stylistic refinement as the classic box-like forms of the previous decade undergo subtle transformations in the direction of softer surfaces and more integrated designs. As previously suggested, the ads of this period are characterized by increasing verbal content. Often gratuitous, this new verbiage tends to upset the older pictorial equilibrium.

An Oldsmobile ad (11) of 1930 well exemplifies this trend, though a neo-Sung dynasty landscape adds a bizarre and individual touch. Smoother and rounder surfaces are the major aesthetic changes in car styling, while the all-steel top and balloon tires represent the major functional additions.

A rare instance of avant-garde design in car advertising is afforded by a Marmon ad (12) of 1930, which appeared in only two issues of Life before being withdrawn, presumably for its lack of effectiveness. All but dispensing with the actual image of a vehicle, the ad seeks to convey its meaning, apart from the new verbal flak, with a few expressive lines and colors. An example of Art Deco design and lettering, the ad stands in marked contrast to those images of static elegance from the decade 1910-1920. The objectified image, that quality of "thing-ness" by which the automobile largely promoted itself, has given way to an evanescent impression of speed.

From the perspective of automotive design the 1935 Chrysler Airflow (13) marks the most abrupt aesthetic departure in the history of the American automobile. With its raking chassis, slanted front and rear windows, integrated headlights and overall fluid lines, it was the first car "designed by committee." It marks emphatically the major point of demarcation between the classic and modern eras of the American car. As seen in a Chrysler ad of 1935, a corresponding change in advertising aesthetics also accompanies this phenomenon. Not only does photography come into wide usage as a replacement for original graphics with a resultant aesthetic loss but new heights of banality are attained through the use of meretricious verbal content.

ART historians have long employed such terms as morphology and evolution to describe forms and processes in the lie cycle of artistic styles. Among the first to apply these principle to the study of the Gothic cathedral was the French medievally Henri Focillon, although he was always careful to avoid strict biological meanings and sought to employ them more as a convenient means of classification. According to Focillon, the life of forms in art is fundamentally a process of "self-definition and escape forms the definition." In turn, the task of the critic is to reconstruct that "pre-existing process."

In this context the development of the 20th century automobile, like that of the medieval" Gothic cathedral, can be reduced to Focillon's schema in terms of several broad categories of style:

Gothic Cathedrals Automobiles Experimental Age 1140-1180 1890-1910 Classic Age 1180-1220 1910-1920 Age of Refinement 1220-1280 1920-1930 Baroque Age 1280-1400 1935-1975

The experimental age: This is the period in the life of any new style in which it is seeking to define itself. It is characterized both by rigid archaisms - older forms attempting to adapt to new meanings (1 & 4) - and newly invented forms - pointed rib vaults, extruded hoods, etc. (2 & 3). The design of cars in this period is characterized by the sharp delineation of parts - separation of hood from scuttle, projecting seats - and the discrete compartmentalization of the engine, driver, and carriage. Linearism is the dominant aesthetic.

The classic age: This is the era of stability which follows upon experimental unrest. The overall severity of design of the Previous period gives way to a greater sublimation of the parts to the whole. In the cars of this period (advertisements 5-10) such Features as front doors are added while seats become recessed, he carriage and power unit are now fully integrated into a uni- tarY design. Severe angularity is modified by softer transitional forms as the more abrupt points of juncture are eliminated, Linearism, however, retains its aesthetic hold.

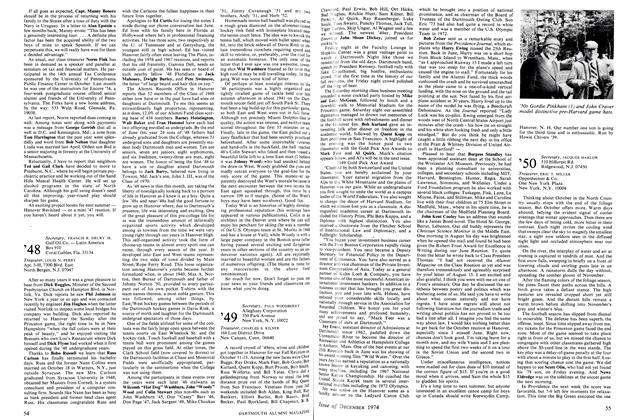

The age of refinement: The design of cathedrals, as well as of cars, in this period demonstrates a new tendency towards attenuated proportions and arbitrary elongations. For automobiles, as depicted in the Oldsmobile ad of 1930 (11), the severe linearism of the classic era gives way to softer modeled surfaces.

The baroque age: This is the period in the life cycle of any style in which forms begin to proliferate, often playing roles independent of the function of the structure. Extravagantly modeled shapes and an overall plastic approach to form, as in the Chrysler Airflow, lead to the elimination of right angles and other linear modes.

HOWEVER this process is perceived, whether as the biological equation of bud, bloom and decay or merely as a process of formal change and transformation, it is nonetheless one in which forms, both architectural and automotive, strive to comply with an internal organizing logic. A still further corollary can be recognized in the almost "organic" relationship between the nature of car design and the quality of advertising aesthetic. For both institutions the era from 1910-1920 represents a unique florescence of style. Thereafter, the aesthetic appeal of the image and artifact enter into sharp decline.

As we enter the era of modern car culture, it is doubtful that the automobile still enjoys the unclouded confidence and esteem "of a whole populace" that Barthes claims for it. Its impact on contemporary space and perception may well be equivalent to the role of architecture in past ages, but its importance as a cultural symbol is vastly diminished. Among many things, the gradual erosion of the ability of the car image alone to carry the weight of its own meaning would seem to bear ample testimony to its currently debased status. Indeed, some critics have attempted to argue that we have already entered the post-automotive era. The advent of electronic communications in combination with the rise of environmental awareness is an alleged major determinant of the obsolescence of the automobile. Perhaps more important is a generally conceded loss of faith in the car's magical properties. Neither bourgeois status nor adolescent rites of passage rely today upon cars for their achievement.

In the second and third decades of the 20th century, however, the car was undoubtedly the "supreme creation of an era." For better or worse it enjoyed a kind of genuine cultural hegemony that, almost uniquely in history, finds its nearest counterpart in the great Gothic cathedrals.

(2) Life, 1905

(1) Life, 1901

(3) Life, 1908

(4) Life, 1909

(5) Life, 1909

(6) Life, 1911

(7) Life, 1910

(8) Saturday Evening Post, 1910

(9) Life, 1913

(10) Life, 1916

(11) Saturday Evening Post, 1930

(12) Life, 1930

Robert L. McGrath, chairman of the Art Department, drives a1965 Volvo, which he categorizes as Neo-Classic. This article isadapted from an Alumni Seminar conducted in Detroit.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: More Food for Thought

December 1974 By JOAN L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureSheets of Sound

December 1974 By SID LEAVITT -

Feature

FeatureOur Crowd

December 1974 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1974 By PAUL WOODBERRY, CHARLES S. KILNER -

Article

ArticleJAMES BRIAN QUINN

December 1974 By R.B.G.

ROBERT L. McGRATH

Features

-

Feature

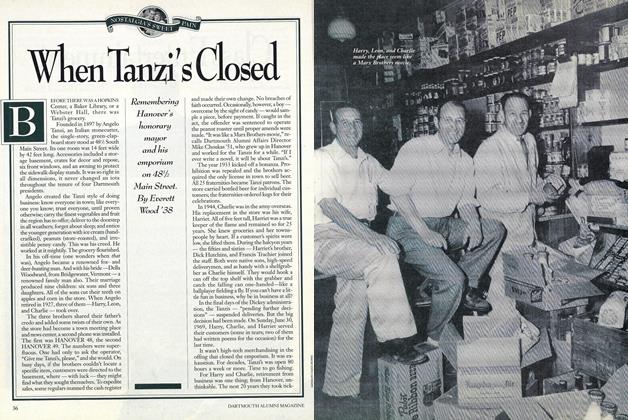

FeatureWhen Tanzi's Closed

MARCH 1991 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

Nov/Dec 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

FeatureTeaching at a Communist University

JUNE 1971 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

FeatureAlzheimer's Disease

MAY 1985 By Peter Blum '85 -

FEATURES

FEATURESCapital Business

MAY | JUNE 2021 By RICHARD BABCOCK ’69 -

Feature

FeatureJournal of a Long Season

March 1974 By TOM EGGLESTON